|

|

John Burroughs: An American

Naturalist

An Afterword to the biography by Edward

J. Renehan Jr.

Note: This Afterword was edited from the

first hardcover edition of John Burroughs: An American Naturalist

(Chelsea Green, 1992). Cick here

for reviews and ordering info at the web site for the publisher

of the paperback edition, Black

Dome Press. Note: This Afterword was edited from the

first hardcover edition of John Burroughs: An American Naturalist

(Chelsea Green, 1992). Cick here

for reviews and ordering info at the web site for the publisher

of the paperback edition, Black

Dome Press.

The day inevitably comes to every author

when he must take his place amid the silent throngs of the past; when

no works can call attention to him afresh; when the partiality of

his friends no longer counts; when his friends and admirers themselves

are gathered to their fathers; when the spirit of the day in which

he writes has given place to the spirit of another and different day

… How will it fare with poor me?

— The Journals,

November 16th, 1897

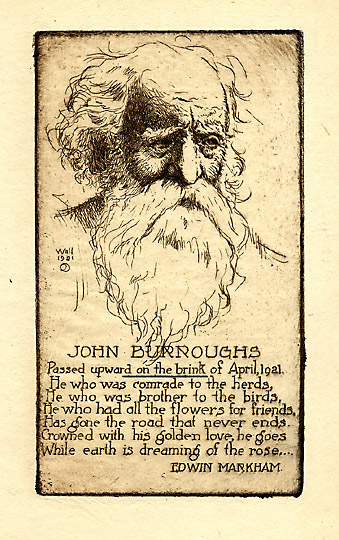

In his will probated

the second week of April, 1921, John Burroughs bequeathed his rustic

writing table to Henry Ford. In the same instrument, Burroughs named

his son Julian executor and beneficiary of his real property: Slabsides,

Riverby and Woodchuck Lodge. (Julian subsequently deeded Woodchuck

Lodge to Henry and Clara Ford, who would own the place until 1947.)

Burroughs also appointed his longtime secretary and mistress, Clara

Barrus, as literary executrix. To her Burroughs willed all income

from his writings during her lifetime. Upon the death of Barrus, the

rights to the literary works were to revert back to the family. Burroughs's

library went to his grandchildren — Elizabeth, Ursula, and John. In his will probated

the second week of April, 1921, John Burroughs bequeathed his rustic

writing table to Henry Ford. In the same instrument, Burroughs named

his son Julian executor and beneficiary of his real property: Slabsides,

Riverby and Woodchuck Lodge. (Julian subsequently deeded Woodchuck

Lodge to Henry and Clara Ford, who would own the place until 1947.)

Burroughs also appointed his longtime secretary and mistress, Clara

Barrus, as literary executrix. To her Burroughs willed all income

from his writings during her lifetime. Upon the death of Barrus, the

rights to the literary works were to revert back to the family. Burroughs's

library went to his grandchildren — Elizabeth, Ursula, and John.

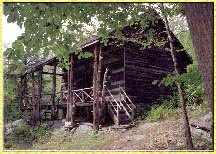

Julian spent the rest of his life at Riverby and died in 1954. The

farm is still owned by members of the Burroughs family. Not far away,

Slabsides and the woods around it remain today just as they were when

Burroughs left them: sanctuaries for nature and for those who find

peace amid it. In addition to maintaining Slabsides, the John Burroughs

Association awards the John Burroughs Medal for excellence in nature

writing. Among the recipients of this annual award have been Edwin

Way Teale, David Rains Wallace, Peter Matthiessen, John McPhee, Aldo

Leopold, Roger Tory Peterson, Laurence Kilham, and John Hay.

After Burroughs died, Clara Barrus dedicated herself to being his

Boswell. This was the task for which she'd groomed herself and interrogated

her subject for years. Leasing Woodchuck Lodge, she was to remain

there to do nothing but write about the house's dead owner for the

next decade. The ever-loyal firm of Houghton Mifflin published Barrus's

two-volume Life and Letters of John Burroughs in 1925, and

Whitman and Burroughs, Comrades in 1931. In the six years between

the appearance of these two large works, Barrus sometimes sold pages

from Burroughs's manuscripts to visiting tourists in order to stay

afloat financially. Barrus died of cancer in 1931, at the age of 57.

During August of 1930, while Barrus was working on the latter book,

novelist Hamlin Garland stopped at Woodchuck Lodge for a visit. "We

found Clara Barrus in possession, or rather we found her obsessed

by the Lodge and its memories," Garland wrote in his diary. "She reports

that people still come to visit the spot, four thousand last year,

and she is on hand to receive them and take them into the dining room

and the little study in which he worked. It was a little more ragged,

a little more musty, than when he lived in it, and all rather painful

to me … I went in reluctantly … It is a futile task, this

keeping dim fires going on the altars of our dead … His monument

is in his books, not in this flimsy cabin." Standing on the porch

with Barrus that summer day of 1930, Garland remembered a similar

afternoon on the same porch with Burroughs and Barrus in 1919. The

old man sat spinning stories to Garland of his life and acquaintances.

Barrus perched herself beside him, anxiously taking down every word.

"He ran over large spaces of his life," Garland recalled, "and as

he talked Dr. Barrus took notes furiously, for he spoke to me with

a spirit and interest which he could not sustain with her. She had

been at him so long that her questions bored him."

Barrus's two last, serious works on Burroughs

did not sell well. By the late twenties, the lion's share of Burroughs's

own books were out of print. The reading public moved on to other

concerns. Tastes and sensibilities underwent a fundamental change.

Burroughs's Gilded Age gave way to Fitzgerald's Jazz Age. The poems

were now by Eliot and Pound, the paintings by Picasso, and the prose

by Hemingway and others of the Lost Generation. In some of his very

last writings, which Barrus hastily scooped up and published in two

posthumous volumes (Under the Maples, 1921, and The Last

Harvest, 1922), Burroughs criticized the new generation of poets

and painters who now, after his death, quickly overshadowed him. Barrus's two last, serious works on Burroughs

did not sell well. By the late twenties, the lion's share of Burroughs's

own books were out of print. The reading public moved on to other

concerns. Tastes and sensibilities underwent a fundamental change.

Burroughs's Gilded Age gave way to Fitzgerald's Jazz Age. The poems

were now by Eliot and Pound, the paintings by Picasso, and the prose

by Hemingway and others of the Lost Generation. In some of his very

last writings, which Barrus hastily scooped up and published in two

posthumous volumes (Under the Maples, 1921, and The Last

Harvest, 1922), Burroughs criticized the new generation of poets

and painters who now, after his death, quickly overshadowed him.

William Beebe was almost apologetic about including Burroughs's

essay "Old Friends in New Places," (from Under the Appletrees,

1916) in his 1941 anthology The Book of Naturalists. Mistakenly

referring to Burroughs as a "New England essayist," Beebe said that

had he not included Burroughs in the book, there would have been left

"a minor but unfillable gap between Thoreau and some of the modern

naturalists." Others looked back upon John Burroughs with higher regard.

Van Wyck Brooks remembered him warmly in The Times of Melville

and Whitman (1947), where he gave a studied appraisal of the man

and his writings, and said Burroughs's work conveyed "the feeling

of a mind really in love with the world, large, alive with curiosity,

perceptive, alert … one could open virtually at random any of

his multitudinous books and count upon finding something memorable

and happy." A few popular nature writers of the 1940s and 1950s —

most notably the Pulitzer Prize winner Edwin Way Teale — took

public notice of the debt they owed Burroughs. Occasionally one of

his books was reprinted. William Beebe was almost apologetic about including Burroughs's

essay "Old Friends in New Places," (from Under the Appletrees,

1916) in his 1941 anthology The Book of Naturalists. Mistakenly

referring to Burroughs as a "New England essayist," Beebe said that

had he not included Burroughs in the book, there would have been left

"a minor but unfillable gap between Thoreau and some of the modern

naturalists." Others looked back upon John Burroughs with higher regard.

Van Wyck Brooks remembered him warmly in The Times of Melville

and Whitman (1947), where he gave a studied appraisal of the man

and his writings, and said Burroughs's work conveyed "the feeling

of a mind really in love with the world, large, alive with curiosity,

perceptive, alert … one could open virtually at random any of

his multitudinous books and count upon finding something memorable

and happy." A few popular nature writers of the 1940s and 1950s —

most notably the Pulitzer Prize winner Edwin Way Teale — took

public notice of the debt they owed Burroughs. Occasionally one of

his books was reprinted.

In 1959, John Burroughs's granddaughter Elizabeth Burroughs Kelley

wrote a nostalgic, heartfelt biography of her grandfather entitled

John Burroughs, Naturalist. Published by a vanity press, the

book did not receive the wide distribution it deserved. Nevertheless,

it remains a vital, intimate portrait of the man. 1968 brought republication

by Russell & Russell of the complete works of John Burroughs,

twenty-three volumes in all excluding only Notes on Walt Whitman

as Poet and Person, Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt, Squirrels

and Other Fur Bearers and the Audubon biography. In 1974 a drastically

oversimplified Burroughs made a brief appearance as a character in

E.L. Doctorow's novel Ragtime. Doctorow painted Burroughs as

a friend of Henry Ford and "an old naturalist who studied the humble

creatures of the woodland — chipmunk and raccoon, junko, wren

and chickadee."

Through the 1960s and 70s, as the environmental movement

emerged as a cultural force, Burroughs and others of his era, particularly

John Muir, began to find a new generation of readers eager for their

message. Muir experienced more of a revival than Burroughs. This was

in part because Muir, in addition to his books, also left behind an

activist environmental organization of his own founding. The Sierra

Club experienced a tremendous resurgence in the '60s after a malaise

of several decades. As the Club revived, so did Muir's popularity

and influence. Reading Muir's books, environmentally-aware young people

found a firm expression of the importance of pristine wilderness and

a distinct call for its preservation. They found something less in

Burroughs: a gentle voice singing the praises of woodlands and the

rural way of life, but generally stopping short of demanding that

the bulldozers be turned back. Through the 1960s and 70s, as the environmental movement

emerged as a cultural force, Burroughs and others of his era, particularly

John Muir, began to find a new generation of readers eager for their

message. Muir experienced more of a revival than Burroughs. This was

in part because Muir, in addition to his books, also left behind an

activist environmental organization of his own founding. The Sierra

Club experienced a tremendous resurgence in the '60s after a malaise

of several decades. As the Club revived, so did Muir's popularity

and influence. Reading Muir's books, environmentally-aware young people

found a firm expression of the importance of pristine wilderness and

a distinct call for its preservation. They found something less in

Burroughs: a gentle voice singing the praises of woodlands and the

rural way of life, but generally stopping short of demanding that

the bulldozers be turned back.

Given all this, what is it that redeems Burroughs? Why is he worth

reading, studying, remembering? The answer is straightforward enough.

In the tradition of his two great heroes Emerson and Whitman, Burroughs

helped point the way for people of modern times to find personal redemption

and transcendence through a life lived closed to and in sympathy with

nature. In a time of decaying creeds, Burroughs proposed an essentially

religious philosophy of nature meant to free people from the cynicism

of the industrial age, rendering them content to accept the universe

and their part in it. In the midst of the Gilded Age, an era of institutionalized

harshness, Burroughs articulated a hopeful, sane prescription for

personal salvation.

In our own modern days of mammon, this most important part of Burroughs's

message remains a necessary, enduring idea.

Click here

to buy John Burroughs: An American Naturalist from Amazon.com.

renehan.blogspot.com

© 2004 by

Edward J. Renehan Jr. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

|

|