|

|

|

|

Chapter XVII

Work And Play In Later Years

|

|

Two essays especially interesting to young readers were written by

Mr. Burroughs at Slabsides in 1899 -- " The Art of Seeing

Things," in Leaf and Tendril, and "Wild Life about my

Cabin," in Far and Near. That spring, when happy in his woodland

cabin, poking about the woods, burning brush, rowing on the Shattega,

and nibbling betimes at his pen, there came a disturbing proposition

-an invitation to go on the Harriman Alaskan Expedition. With all his

curiosity about new lands, he shrank from such a departure from his

quiet life, but after debating the question, finally turned the key

in the door of Slabsides, journeyed across the States, and, on the

last day of May took ship at Seattle for Alaska.

Mr. E. H. Harriman and family were joined on this expedition by about

forty well-known scientists and artistsbotanists, geologists,

zoologists, ornithologists, and so on. There was John Muir, the Great

Ice Chief, Dr. Fernow, the Tree Chief, Dr. Grinnell, the expert on

Indians, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, the bird portrait painter, and many

others eminent in various fields. Mr. Muir knew so much about

glaciers, and so considered them his special property, that he hardly

allowed anyone else an opinion concerning them. Perhaps of all the

thrilling experiences on that expedition of so many thrills, the

chief was that early encounter with the glacier named after their

fellow voyager. Approaching its front to within two miles of its

crumbling wall of ice, which towered two hundred and fifty feet above

them, they dropped anchor near the little cabin where the Great Ice

Chief had dwelt some years before when he discovered the glacier.

They heard the deafening explosions as enormous masses separated,

were submerged, then slowly rose like monsters of the deep, their

blue forms gradually emerging from snowy clouds of foam. One day

while near the Muir, a half mile of the front detached itself,

arising again in floating bergs as blue as sapphires.

They visited greater glaciers later, the greatest of which was the

Malaspina, one hundred and fifty square miles in extent, with a

fifty-mile front on the sea, and running back thirty miles or more to

the Saint Elias Range.

At Port Wells, the extreme northeast arm of Prince Williams Sound,

they entered another great ice-chest of glaciers. There were, he said:

Glaciers to right of them,

Glaciers to left of them,

Glaciers in front of them, which

Volleyed and thundered.

To many of these they gave names-Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Amherst,

Radcliffe, Smith, Bryn Mawr, Vassar, and Wellesley.

While exploring in the vicinity of the Barry glacier, where a ship

had -never gone before, they encountered a mighty obstacle

effectually barring their way, later named the Harriman glacier. It

was while there that their vessel was caught in a strong ebbing tide,

and, hesitating to respond to the helm, seemed for a brief period to

be making directly for the lofty wall of ice on their port side; but

happily the ship soon came about, and on they sailed merrily.

The Seal Islands, the paradise of Kadiak, the Kadiak bear and cub

which Mr. Harriman shot, the woods upholstered ankle-deep with moss,

the winsome flowers, these and much else are engagingly described in

Far and Near. In the New York Zoological Park and also in the Peabody

Museum at Harvard University are totem poles which- they brought back

from that expedition.

Of course the bird life in Alaska especially interested Mr.

Burroughs. Will he ever forget the humming bird he saw on the Muir

glacier, carried by its tiny wings three thousand miles or more? Some

birds there were which set him to rhyming-the Oregon robin, the

golden crowned sparrow, and the Lapland longspur, the last-named

reminding him strongly of his boyhood bobolink:

On Unalaska's emerald lea,

On lonely isles in Bering Sea,

On far Siberia's barren shore,

On North Alaska's tundra floor,

At morn, at noon, in pallid night

We heard thy song, and saw thy flight,

While I, sighing, could but think

Of my boyhood's bobolink.

He never tired of watching the albatrosses which followed their ship

in effortless flight, or the Arctic terns, as with sickle-like wings

they reapt the air. There they saw the little water ouzel, and the

golden plover with its soft and plaintive call. The familiar barn

swallows in that land without barns, seemed at ease; song sparrows,

though nearly as large as catbirds, were much like those of the Catskills.

In Bering Sea, while making its perilous way toward Siberia through

night and fog, the George W. Elder suddenly grated on the rocks. She

trembled from stem to stem. Terrified, all on board sprang to their

feet in mute alarm; but the engines were quickly reversed, a sail was

hoisted, the ship's prow soon swung to the right, and they were again afloat.

In speaking of this trip Mr. Burroughs often says that he travelled

two hours in Asia, and was tempted to write a book about it, but

thought better of it. When we read what he did write of that first

glimpse of Asia, "crushed down there on the rim of the world, as

though with the weight of her centuries, and her cruel Czar's

iniquities," we wish he had not checked his impulse.

Of all the live stock that went aboard the ship at Seattle -steers,

sheep, chickens, turkeys, and horses-nothing remained at the end of

the voyage but one dependable cow which had gone with them to Siberia

and back, and given milk all the way.

Since 1900 Mr. Burroughs has led a more varied and eventful life than

theretofore. His son had entered Harvard two years previously, which

in itself took him frequently to Boston, and, the "habit of

gadding" once established, frequent jaunts became customary. He

entered eagerly into the college life, going with Julian to football

and baseball games and rowing contests.

During the hours he spent in the library at Harvard while editing his

Songs of Nature, he became inoculated with the germs of the rhyming

fever, and made many rhymes himself, the most of which he gathered

later into Bird and Bough.

The fall of 1901 was. a memorable one to the writer, in that she then

made the pilgrimage to Slabsides which resulted in her friendship and

long association with John o' Birds. Mr. Burroughs, then working on

the Life of Audubon, for the Beacon Biography series, was finding the

work, not self-elected, irksome indeed. It* dragged. Finishing

touches on Literary Values were also occupying him. He wanted much to

strike work and run away to Jamaica with a friend and his son. At

length he did run away, entrusting the writer with some of the

mechanical work on those volumes, and with seeing the Audubon through

the press. Hence it has come about that of the last twelve volumes

which have come from his pen (and of three more nearly ready to see

the light), the writer has had the privilege of cooperating with the

author, relieving him, by typing, proof-reading, and attention to

some of the drudgery connected with bookmaking. Twelve books from the

age of thirty to sixtyfour, and fifteen since he has passed the

four-and-sixtieth milestone! Dr. Osler's much-quoted dictum as to the

comparative uselessness of a man after forty is hardly applicable to

Oom John!

|

|

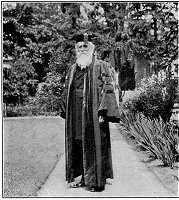

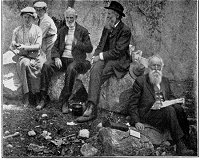

The West Settlement pupil taking honorary degree

at Yale |

Mr. Burroughs has said that when (in February 1902) he went to

Jamaica, he lost February and found August. And in his "Lost

February," his reader finds that he has, on the whole, little

admiration for that land of perpetual summer. In fact, we sometimes

find him railing against the barbaric Nature encountered there-Nature

without the lure of spring, the repose of autumn, or the sternness of

winter! Nature with her spikes and spines, her stings and stabs, her

rustling and tattered foliage varnished by sun and tropic heat, her

fleas and her sand-ants and mosquitoes, her lairs and her

jungles-brilliant, barbaric Princess-too ready with her fangs, too

chary of tenderness and charm.

And yet we find him saying a good word for the Blue Mountains, the

limpid streams, the morning-glory colours of the Caribbean, the soft,

luminous nights with the Southern Cross hanging low on the horizon;

and above all for the shy solitaire, or "shine eye" -- a

bird seldom seen but often heard, whose melodious and plaintive

strain -"a series of tinkling, bell-like notes," with an

appealing, flute-like ending -- entirely won his heart. |

|

And barbaric Nature treated him to many a novelty he would not have

missed-the flying-fish with their mechanical flight, the curious

behaviour of the "shame lady," or sensitive plant, the clownish-looking

tody in suit of green and massive yellow beak, the mongoose, the

queer-looking East Indian oxen, the nearly black humming bird with

the two long plumes in its tail, the lubberly pelicans diving for

fish, the giant fireflies, so large the travellers thought their

lights to be those of the elusive town they were seeking, and then

that strange Cock Pit Country with the rough-hewn rocky bowls

hundreds of feet deep and a thousand or more feet across.

Nevertheless, on his return to familiar scenes, the robins he heard

carolling in the treetops at sundown pleased him better than anything

seen or heard in Jamaica. |

|

The bark study and summer house |

During the spring of 1902 our author had keen

delight in helping his son get out stone for the foundations of his

cottage built at Riverby, a few yards to the left of the Bark Study.

Then the excitement of discussing the building plans, and the

pleasure of watching the house grow, and the joy in the fall when the

young couple moved in and set up house-keeping in Love-cote,

as the cottage was at first named!

After the Jamaican trip, some winters or parts of winters have been

spent in Bermuda, in Washington, North Carolina, Georgia, and

Florida, some on the Pacific Coast, some yachting around Cuba, in the

Sialia (The Blue Bird) with Mr. Henry Ford, while some have also been

cosily spent in The Nest at Riverby, or in the luxurious simplicity

of Yama Farms Inn, in the Shawangunk Mountains.

|

|

In 1903, our veteran literary naturalist became disturbed over the

growing tendency of certain writers to misrepresent Nature-romancing

about her when purporting to give straight natural history. With

fiction undisguised as fiction, he had no quarrel, but for fiction

disguised as natural history he had 'the utmost scorn, so he put on

the gloves, entered the arena, and delivered knockout blows to the

traducers of his mistress. The first bout was in an essay in the

March Atlantic, in 1903, "Real and Sham Natural History."

Many another followed for a year or two, the records of which are

mostly to be found in his volume called Ways of Nature. It was all a

contention for clear seeing and honest reportingin other words, a

demand for a square deal with Nature. |

|

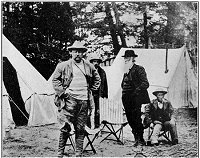

John Burroughs with Theodore Roosevelt in Yellowstone

|

Seeing a scrap on between Oom John and those whom he dubbed Nature

Fakers, the valiant Roosevelt soon came bounding in the ring,

striking out right and left with the Big Stick, belabouring the

offenders unmercifully, almost skinning them alive! Their joint

efforts laid many an offender low, and many another, convinced that,

after all, honesty is the best policy, straightway reformed. In time

the belligerents cooled off and shook hands, and nature faking became

as a tale that is told.

Back in his ranch days Theodore Roosevelt had written ardent letters

of appreciation to Mr. Burroughs about his books, and they had met on

various occasions-when Roosevelt was Civil Service Commissioner, when

he was Governor, when Ted had been to Slabsides for a day or two, and

Ted's father had wanted to go but had been too busy setting right

certain places in the political world that were out of joint. But it

was not until 1903 that the intimate friendship between these two

men, so opposite in type, age, character and training, began. They

had one passion in common-love of Nature, though courting the Dame in

such diverse ways. |

|

In the spring of 1903, when that Big Boy who was playing the game of

being President, and playing it for all he was worth, began to pant

for the wilds, he decided to take a vacation, Congress or no

Congress, in Yellowstone Park, and asked John Burroughs to take it

with him. The yellow newspapers, getting wind of the trip, made much

of it, calling it a hunting trip, assuming that the President was

going into the Park to kill the elk and moose and caribou. Some of

the correspondents of Mr. Burroughs hoped he would rebuke the

President by refusing to go with him. A Vermont woman wrote urging

him to restrain the Hunter as much as possible, and teach him to love

the animals as he did. "She little knew," confessed Mr.

Burroughs, "that I myself was cherishing the hope that I might

shoot a cougar or a bob cat. But as a matter of fact, the President

did not go there to hunt. He did not once fire a gun in the Park."

In each city along the route there was a round of handshaking,

dining, and speech-making for the Strenuous One who, though declaring

it needed the strength of a bull moose to stand it, seemed to thrive

on it, keeping fit as a fiddle all through. |

|

The boy in the President came out continually on this trip, and the

elder boy concluded that was why they "took" to each other

so readily. Roosevelt's unfeigned delight at the hearty

demonstrations along the way was refreshing. And when in St. Paul, as

their carriage was slowly creeping along in the crowds, they spied a

band of schoolgirls carrying a banner-" The John Burroughs Club

"-and a blushing maiden pushed her way to the President's

carriage and timidly thrust a bouquet on the lap of Mr. Burroughs,

the President was greatly tickled.

On this trip Roosevelt gave the name of Oom John to our friend.

Saying that he felt like a hen with one chicken, he lived up to this

feeling and scratched around and hovered over his lone charge with

kindly care. As for Oom John, being a Slabsider, and not having

hobnobbed with presidents before, he was at a loss how to address his

host. Should he call him Your Excellency, which they say Washington

exacted, or Mr. President, or what? As His Excellency was much averse

to that epithet, they compromised on His Transparency-as having at

least the merit of accuracy!

One day at luncheon, while passing a little settlement in Dakota,

they saw a teacher and her pupils watching eagerly as the train

passed. Jumping up, with napkin in hand, the President rushed to the

platform and waved to them. "Those children wanted to see the

President of the United States," said he, "and I couldn't

disappoint them-they may never have another chance."

T. R. bubbled with joy when the former foreman of his Elkhorn Ranch,

a cowboy friend, boarded the train and rode with him a ways. He

bombarded them with questions, recalled events and people they had

long since forgotten, remembering even the names of their dogs and

horses. At twilight, as the train entered the Bad Lands of North

Dakota, he stood on the rear platform and gazed wistfully on the

scene. The Bad Lands, over which he had tramped in all seasons,

evidently looked very good to the one-time Rancher.

When they entered Yellowstone Park a fine saddle horse was waiting

for the President, but an ambulance drawn by mules for Oom John.

Somewhat chagrined at being met by such a vehicle, he nevertheless

stepped inside as though accustomed to ambulances. With an escort of

officers, soldiers, and cowboys, the President, tickled at leaving

reporters and politicians behind, started gaily off, the ambulance

following. And it immediately followed at such a lively pace, swaying

from side to side, that Oom John, grabbing the seat with both hands,

said to himself, " This is a Wild West send-off in dead

earnest." Faster and wilder grew the ride. Tossed about, he

rubbed his bruises with one hand, and clung to the seat with the

other. Presently, looking out, he saw the cowboys scrambling up a

bank, and the President on his fine stallion, scrambling up there,

too, and looking back fiercely as the ambulance thundered by.

"This is certainly the ride of my life," thought Oom John.

" I seem to be given the right of way-we have even sidetracked

the President!" On they tore for a mile or more till, on

reaching Fort Yellowstone, he learned that the mules, excited by the

presidential cavalcade, had been running away, the driver's only

course being to keep them in the road till the hill at that point

should give them pause.

The Mammoth Springs in the Park were all that they were "cracked

up" to be. The columns of vapour, the sulphurous odours, the

unearthly beauty of colour - were all things of which Oom John had

never seen the like before. In one of the steaming pools, about an

acre in extent, they saw a pair of mallard ducks swimming, the ducks

moving to the warmer waters as the party came near. At length, the

waters getting too hot for them, they took to their wings, else the

travellers might have had boiled mallard for dinner. In a certain

pool they caught a trout, and without changing their position, cast

the fish into another pool and cooked it.

For Mr. Burroughs the novelty of the geyser region soon wore off. He

says that steam and hot water are the same the world over, and he

hated to see so much of it going to waste. The Growler, he said, was

only a boiling tea kettle on a huge scale. Old Faithful was another,

with its lid off, and its contents thrown high in the air. In fact,

he cares little for Nature in her spectacular moods. I remember how,

in the Hawaiian Islands six years later, he tired of the lurid

spectacle of Kilauea long before the rest of the party did.

Eventful was every hour in the Park-whether listening to Townsend's

solitaire, or to the singing gophers; catching sight of black-tailed

deer, or blue grouse; whether meeting with the Duke of Hell-roaring

Creek, or treeing the pigmy owl -- a bird not much larger than our

bluebird -which the President was as happy to get in range of his

opera glasses as though he had bagged some bigger game.

One day while making their way down a valley on horseback, T. R.,

ahead, saw a band of elk a few hundred yards away. Wheeling to the

left, he beckoned Oom John to follow, then tore after them. Now Oom

John had not been in a saddle since the President was born, but he

followed as fast as he could, over rocks and logs and runs. T. R.

would now and then look back and beckon impatiently for him to follow

faster, as though saying to himself, "If I had a rope around

him, he would come faster than that!" At last, his horse

puffing, Oom John came up with the President, tarrying at the brow of

the hill; and there, scarce fifty yards away, their heads turned

toward their pursuers, their tongues hanging out, stood the panting

elk, by their whole bearing seeming to beg for mercy. And there sat

the President laughing like a boy, delighted at this near view of the

noble creatures, and glad to have Oom John see them with him.

Later in the day, from an elevated plateau, they looked down upon

fully three thousand elk at one time. In that sightly spot they

dismounted and stretched themselves in the sunshine on the flat

rocks. The President had his elk, but around Oom John, if the truth

must be told, there skurried tiny chipmunks, half the size of those

of his native hills, toward which he was drawn far more than to the

horde of noble animals they had come so far to see.

One day at Tower Camp, when Billy Hofer, the guide, shouted that a

band of mountain sheep were plunging down a sheer wall of trap rock

to the creek to drink, all rushed to see the sight. The President,

coat off, and towel on neck, had one side of his face shaved and the

other lathered when Billy shouted the news.

"By Jove! I must see that," he cried -- "the shaving

can wait," and T. R. ran with the others to the brink where they

saw the sure-footed creatures leaping down the rock, loosening stones

as they went, pausing on narrow shelves, then plunging down, down,

without accident, to the stream.

Their jolliest times were evenings around the fire when Roosevelt

talked of his ranch days, of the world of politics, of books, of his

travels, of everything under the sun, moon, and stars. Once in a

never-to-be-forgotten talk he took his hearers with him up Kettle

Hill, recreating the scene for them. They saw the Leader's face

blanch, as he confessed it did, when, on looking across an open

basin, he realized that they had to charge up that hill. They saw the

storm of bullets, they heard the shout, "We'll have to take that

hill!" They saw the lines of the Ninth Cavalry part, as their

officer in command, waiting for orders, let Roosevelt and his men

charge through, their intrepidity causing the coloured troops to

swing into the charge also. And, finally, they saw the crest of the

hill swarming with Rough Riders and coloured troopers.

One of the jolliest stories that Oom John remembers is of a Rough

Rider who once wrote to the President for help and sympathy from a

jail in Arizona: "Dear Colonel," the letter ran, " I

am in trouble. I shot a lady in the eye, but, dear Colonel, I did not

intend to hit the lady -- I was shooting at my wife." And over

the tree-tops rang the "dear Colonel's" laughter as he told

of it.

The President did not use tobacco in any form, to the delight of Oom

John, who so loathes tobacco smoke that, while it is enveloping him,

he loathes the smoker also.

Although Roosevelt kept his word about killing big game in the Park,

there was one wild creature that fell a victim to the hunter's

instinct. As they were riding along in a sleigh one day he suddenly

jumped out and, with the help of his sombrero, captured and killed a

mouse running over the ground. It was a rare variety. He skinned and

prepared the pelt and sent it to the National Museum. Oom John

crosses his heart and says this is the only game the Great American

Hunter killed while in the Park. A week or two later, in Spokane,

this incident gave Oom John a sleepless night, for after having told

a crowd of people about the capture of that mouse, he got to worrying

for fear a malicious reporter, or a stupid typesetter, might change

the u to an o, so quoting him as saying that the President had killed

a moose.

Racing with Roosevelt on skis in the Park was attended with mishaps

and ignominious plights for both, until they "got the hang of

the pesky things." Once, gaily passing T. R., floundering in the

snow, Oom John called out something about the Downfall of the

Administration, only to come to grief later and hear T. R. call out,

"Who is laughing now, Oom John?"

The correspondence of J. B. and T. R., extending over the years, is

of value, not only for its natural history interest, but in its

portrayal of character, the President turning easily from affairs of

State to tell of the arrival of the whitecrowned sparrow on the White

House lawn, a purple finch's nest at Sagamore Hill, the

identification of the Dominican warbler, or of putting a half-fledged

flicker back into its nest -- "What a boiling there was when I

dropped it in!" Writing of reluctantly shooting the rare

warbler, and sending its skin to the American Museum, T. R. said,

"The breeding season was past, and no damage came to the species

from shooting the specimen, but I must say I care less and less for

mere 'collecting' as I grow older."

One day at Sagamore Hill Roosevelt showed Mr. Burroughs a bird

journal which he had kept in Egypt, when a lad of fourteen, and a

case of African plovers he had set up at that time. That day they

examined the skin of a gray timber wolf, and especially its teeth,

barely more than an inch long, and had a good laugh at the idea of

such teeth reaching the heart of a caribou through the breast with a

snap, as a certain nature writer, over his affidavit, had shortly

before reported one to have done. Oom John said he doubted if they

could reach the heart of a turkey gobbler in that way; and T. R. said

one might as well make an affidavit that a Rocky Mountain pack-rat

could throw the diamond hitch. As they discussed this and kindred

other impossible statements concerning the wild creatures, one can

imagine T. R. fairly snapping his teeth while declaring he would like

to skin alive the deliberate perpetrator of such lies. Boys don't

mince matters, nor always choose their language with extreme nicety,

and this boy, who knew what he was talking about, not only delighted

in showing up the nature fakers publicly, but in private also let off

steam in such expressions as, "What a pestiferous liar that

fellow is!"

The last outing T. R. and Oom John ever had together was down at Pine

Knot, a secluded place in the woods of Virginia, about a hundred

miles from Washington, where they went to name the birds without a gun.

The night before leaving Washington, at dinner in the White House,

one of the guests being an officer in the British army, stationed in

India, Oom John was amazed to see the extent of the President's

knowledge of Indian affairs, for all the world as though he had been

cramming for a Regent Examination on the subject. But the next

morning, India, England, and even affairs of the United States were

given the cold shoulder, as the bird lovers took an early train for

Pine Knot.

The spring migration of warblers being on, Roosevelt was not content

to ride the ten miles to the cabin, so both boys jumped from the

wagon and began the race of identifying the warblers. The younger boy

with his "four eyes," two of which were not first class,

kept up with Oom John's sharp eyes, matching a black-poll with a

redthroated blue, and a Wilson's black-cap with a pine warbler. After

reaching the cabin, they started off on another bird hunt, T. R.

walking as if for a wager, through fields and briers and marshes. At

last, pausing and mopping their brows, they turned back, having seen

few birds.

Mrs. Roosevelt evidently took the Strenuous One to task for rushing

their guest about in that fashion, for he came around apologetically

later and said, "Oom John, that was not the way to go after the

birds-we will do differently tomorrow," and the Saunterer who

never makes a dead set at the birds, admitted that he had never gone

a-birding just that way before.

On the morrow they named more than seventy-five species of birds, of

which Mr. Burroughs knew all but two, and the President all but two,

the President having taught J. B. the prairie warbler and Bewick's

wren and J.B. having taught him the swamp sparrow and one of the

rarer warblers. If T. R. had found Lincoln's sparrow, which he

usually found there, he would have gone Oom John one better. They

loitered in a weedy field a long time, while the President kept his

eye peeled for that sparrow, but the sparrow may have been keeping

his eye peeled also, for he never came in sight.

One evening at Pine Knot as they sat around the table reading, Mrs.

Roosevelt busy with needlework, Roosevelt occupied with Lord Cromer's

book on Egypt, and J. B. deep in the horrible account of the

man-eating lions of East Africa (the lions carrying their victims

into the bushes, and purring as they crunched their bones), suddenly

T. R.'s hand came down, on the table with such a bang that Mrs.

Roosevelt fairly jumped from her chair, and J. B. thought a lion had

him sure.

"Why, my dear, what is the matter?" asked Mrs. Roosevelt in

a slightly nettled tone.

" I got him!" triumphed the Slayer-he had killed a

mosquito, expending enough energy almost to have demolished an

African lion.

When on the return trip, his secretary boarded the train, the

President was soon deep in the dictation of letters and the

consideration of many weighty matters-wrens, warblers, and the

sparrow he did not find, side-tracked for the business of the Administration. |

|

In Yosemite with John Muir |

When in February, 1909, Mrs. A- and I went to the Pacific Coast in

company with Mr. Burroughs, and on to the Hawaiian Islands, we

considered ourselves two of the luckiest women in the United States.

Mr. Muir was to meet Mr. Burroughs in Arizona, and conduct him

through the Petrified Forest region, in and around the Grand Canyon,

camp on the Mojave Desert, tarry awhile in Southern California, and

pilot him through Yosemite Valley.

As usual, Mr. Burroughs hesitated about going, telling himself he

might better court Nature from his own doorstep, but the Call of the

West won the day. |

|

My friend and I wondered how Mr. Muir would relish two women tagging

along, but were assured by Mr. Burroughs that it would be all right

so long as we were good listeners!

That night when we got off the train at Adamana, a voice called out

from the obscurity:

"Hello, Johnny, are ye there?"

"Yes, Muir, and with two women in my train."

"Only two, Johnny?" Then to us, "In Alaska there was a

whole flock of women hovering around him, tucking him up in rugs,

bringing him a bird or a flower to name, putting a stool at his feet,

and sitting there in rapt admiration to catch the pearls of wisdom

which did not fall from his lips -- Oh, two is a very moderate

number, I think, Johnny!" And the tall, grizzly, teasing Scot

led the way to the little inn. And the next day he led the way across

the trackless desert, he and the silent driver in the black sombrero,

Mr. Muir talking all the way, the most racy talk I ever heard; talk

of lonely wanderings on mountains and glaciers; of his long walk from

Wisconsin to the Gulf; of trees and ferns in foreign lands; of his

boyhood home in bonny Scotland; talk of storms, earthquakes,

avalanches, waterfalls; talk of men and women; of scientists, of

poets; of everything under the sun; talk grave and gay, sidesplitting

anecdotes one minute, tear-provoking recitals the next. On and on we

rode, and on and on he talkedunless, haplessly, some one introduced a

question, and then, thrown off the track, the monologist would find

difficulty in resuming his theme, and the luckless questioner would

be treated to a jibe or a hectoring remark.

Mingling with his racy monologue were the impressions being

continually borne in on us of the illimitable, desertlike expanse

stretching away on all sides-the gray-green vegetation, an occasional

leaping jack rabbit, a band of wild horses flying in the distance,

and far, far away the curiously carved pink and lilac and purple mountains.

We lingered for days in those petrified forests where the giant

trees, which had swayed in the wind millions of years ago, now lay

stretched out for many acres over the sand, or projected from the

brilliantly coloured. buttes and mesas. Some of them were one hundred

and fifty feet long, and five to seven feet in diameter, straight and

tapering, no branching as in the trees of to-day. Many were as though

sawed into stove lengths. The sand about was strewn with white,

glistening chips. We ate luncheon from one of those prostrate trunks

whose beautiful wood had been changed to beautiful stone, and from

the fissures picked out specimens of jasper, chalcedony, and agate.

One of the three forests which we visited had been discovered by Mr.

Muir and his daughter Helen while riding over those plains some years before.

The morning we reached the Grand Canyon, Mr. Muir preceded us to the

rim, and waving his long arm said, "There! empty your heads of

all vanity, and look"' In awed silence we gazed upon the great abyss.

Mr. Muir jeered at us for wanting to make that perilous descent into

the Canyon on muleback. "Why need you straddle a mule and go

down that steep winding icy trail, just to get a few shivers down

your backs, when you can see the sublimity and glory here from the

top?" Thus he talked, but when, on that mild March day, we did

go down Bright Angel trail he, too, straddled a little mule and went

down with us, though, save for occasional comments to

"Johnny" on the geology of the canyon, his remarks were,

for once, few and far between. I think he was only a few degrees less

frightened than we were. We ate luncheon four thousand feet below the

rim, and looked down another thousand or more upon the Colorado whose

hoarse voice we could hear from the Cambrian plateau.

One day while standing at Hopi Point and getting a new and vivid

realization of the glory and magnitude of the "Divine

Abyss," and of our incalculable privilege, I exclaimed to my

friend, " Think of having all this, and John Burroughs and John

Muir thrown in!"

"I sometimes wish John Muir was thrown in," retorted J. B.,

"when he gets between me and the Canyon!"

Mr. Muir told us that when he first saw Yosemite, he and a young man

walked most of the way from San Francisco, traversing the great San

Joaquin valley, scaling mountains, conquering almost impassable

heights and depths, and how when at last they stood and looked down

into the chasm, the intrepid youth, who under Muir's guidance had

balked at nothing, exclaimed, "Great God! have we got to cross

that gulch, too?"

As we drove into the valley from Chinquapin Falls, and first saw

mighty El Capitan guarding the entrance, Mr. Muir called out,

"How does this compare with the Esopus Valley, Johnny?" But

his bantering soon ceased, for in the presence of that beauty and

sublimity he became reverently mute. Later he told us that when

Emerson was in the Valley, he had said that of all the wonders of the

West, Yosemite was the only thing that came up to the brag. The sheer

granite walls, over three thousand feet high, topped by majestic

trees, the thundering waterfalls, the level grassy floor, the placid

river, which on its way thither had been so turbulent-what a

never-to-be-forgotten scene! |

|

While in the Valley Mr. Muir told us of his struggle as a lad to get

his education. He lived on fifty cents a week while going through

college, and jealously counted the crackers and watched in dismay his

candles dwindle. "But," said he, "all that ended when

I got in the Valley. I was still poor, but there were things here to

fatten my soul." He described his glorious Sunday raids on the

heights, tracing waterfalls to their sources' eating and drinking

beauty and sublimity, and descending the perilous cliffs by night to

be on hand Monday mornings for work in the saw-mill.

While we were there he was much exercised over the question of San

Francisco levying on the lesser Yosemite, Hetch Hetchy, for its

increased water supply. Though unwilling to give up the fight to keep

the utilitarians out, he admitted that the desecration might have to

come in time, adding, "The Lord himself couldn't keep the Devil

out of the first reservation that ever was made."

When we lamented that we must leave without going to Glacier Rock,

Mirror Lake, the Mariposa Grove, and so on, Mr. Muir tauntingly said,

"Yes, I pottered. around here ten years, and you think you can

see it all in four days. You excuse yourselves to God Almighty, who

has kept these glories waiting for you, by hurrying away 'I've got to

get back to Slabsides,' 'We want to go to Honolulu!"'

It was something of a triumph to get Mr. Burroughs to embark on the

Pacific for Hawaii-it seemed so far away from home -- although when

there, he lost his heart to the happy isles, the rainbow sea, the

"liquid sunshine," the warmhearted people. He liked the

look of the childish natives with their leis of flowers; liked the

courteous Japanese; the charmed valleys; the weird Hawaiian music;

yes, and he liked the sweet-fleshed papayas (melons which grow on

trees) and the luscious mangoes. He drew the line, however, at taro

and poi -- the latter, which he tried at a native luau (feast)

tasted, he said, like sour library paste.

One day a teacher in the public schools, thinking to impress upon her

pupils what Mr. Burroughs stood for in literature, gave them a little

talk about him and his work, ending, by saying, "And this

well-known author is now a guest in our city-you may see him on the

street; he has a youthful step and young looking eyes, though his

hair and beard are white-"

" I know," piped up a little lad, " I saw him

yesterdayhe was in our yard stealing mangoes."

Mr. Burroughs enjoyed the great extinct crater, Haleakala, on Maui,

more than he did the great active volcano, Kilauea. He soon tired of

that boiling, tumbling, everchanging lake of fire which threw its

fountains of molten lava sixty or more feet high.

After six weeks of lotus-eating in those tropic isles, we embarked on

the Manchuria, laden with fragrant leis, and with a basket of the

beloved mangoes; threw back our leis to the waiting friends on shore

(in obedience to the tradition that, so doing, one insures his return

to those isles); while the tender strains of Aloha came floating to

us, outward bound.

In the winter of 1911, Mr. Burroughs again went to California, Mrs.

Burroughs accompanying him. Out of the previous trip grew the essays,

"The Divine Abyss," "The Spell of Yosemite," and

"Holidays in Hawaii."

|

Footnotes:

- In 1914, when his son moved away, the cottage, rechristened

The Nest, became the home of the writer, with whom Mr. and Mrs.

Burroughs came to live - (Return)

|

|