|

|

|

|

Catskill Mountains

A visit to the Mountain House

From the Boston Recorder And Telegraph Oct. 6, 1826 |

|

|

The town of Catskill is not visible at landing. It is built beyond

the ridge which rises from Hudson, upon the declivity to a small

creek whose banks are western boundary of the village. The principal

street is about half a mile in length, nearly parallel to the river.

The buildings are neat, and the town wears an appearance of

cleanliness, far beyond most towns upon Hudson. The banks of the

creek opposite the town are very picturesque, rising at the entrance

abruptly, and farther in with every variety of slope, studded with

clumps of trees, and in a high state of cultivation. They afford fine

sites for building, and will probably with the growth of the place

become its chief beauty.

We started for the mountain at 4 o'clock. The distance to the House

is 12 miles, and the ascent occupies about 5 hours. The road for the

first 8 miles is highly interesting -- passing over elevations,

mountains in themselves, and crossing a broad valley whose fine

cultivation, graceful outline and woodland, combine to make a picture

like a creation of poetry. What is called the ascent commences about

3 miles from the summit. There is a good carriage Road; but it is

uncomfortably steep for a ride, we got out to pursue our way on foot.

This you know is classic ground; and you are very gravely assured by

the inhabitants of the valley, who have been questioned about Rip Van

Winkle till they believed it to be a veritable tradition from their

ancestors, that it is the identical path up which Rip toiled with the

contents of the oblivious flagon. |

|

|

Two miles from the summit is a small hut, or shantey as they

are called here, whose occupant by universal consent bears the name

of the immortal sleeper. Whether a genuine descendant or not is the

point upon which I will not state my veracity. His hut is in a

singularly romantic situation; built in a deep angle of the rock with

a perpendicular ascent fifty feet directly above him. He keeps

refreshment for travelers, and is supplied with water by spout which

is laid from his window to the spring in a rock behind him. It was

just dark when we arrived there, and probably the deep shadows of the

woods and rocks added to the effect - but I have seldom been so

struck as by the sudden turn which brought me upon the wild eyrie of

this modern Rip Van Winkle. |

|

We toiled on at the rate of a mile and a half an hour, keeping at

that pace far in advance of the carriage, and growing more vigorous

as we came into the bracing atmosphere of the summit. Perspiration

became very free, as the tenuity of the air increased, and I felt as

if every trace of bodily infirmity oozed with it from my pores. I

could have shouted with the exhilaration and elasticity which grew

upon me. Command me to mountain air and free limbs, if ever I am hyp-ridden.

I forgot to speak of the sun-set, and perhaps it was better. But I

will merely assert that the local advantages of a bold horizon, high

atmosphere and interposed water combine to render the

"gloamings" of Catskill valleys beyond conception beautiful. |

|

|

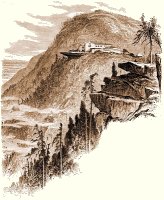

We reached the house about 9 o'clock buttoned to the throat, and

breasting a chill November blast. Fifty feet below we had stood at a

turning in the road, peering through the darkness to get a glimpse of

the House, which we at last discovered perched on a perpendicular

rock, rising almost from our feet. The road which pursues a zig zag

course all the way up the mountain, here made several abrupt turns

and brought us very suddenly to the broad tabular rock upon which the

House is set. We could hardly realize it. After threading in the dark

for two or three hours a perfect wilderness, without a trace save our

narrow road, to burst thus suddenly upon a splendid hotel and,

glittering with lights, and noisy with the sound of the piano and the

hum of gaiety - it was like enchantment. |

|

I seated myself in the drawing room, and was for a moment

bewildered. It was in keeping with the place; for so was Rip Van

Winkle when he woke upon that very spot. But to find myself in an

elegant room, fashionably furnished, and thronged with people

promenading to the sound the piano - in such a place! - a long beard

and a rusty gun were trifles to it. To return to tangible

impressions, however - my supper convinced me that it was not fairy

land, and a view of the promises satisfied me of their

substantiality. The house is a large wooden building, capable of

accommodating two or three hundred people. It makes a fine

appearance, is well-painted, and has a noble piazza running the whole

length of the front. The host is uncommonly polite and gentlemanly,

and his table and rooms afford all the comforts and most of the

luxuries of the city. I went to bed, and having added my cloak to a

winter provision of covering, I was sensible of the single impression

of comfort as I heard the wind whistling at the window, and slept as

a well man sleeps.

I rose the next morning at day break to see the prospect. It was a

clear cold morning, and the minute points of a view with a radius of

50 miles were distinctly visible. The magnificent prospect from this

mountain has been often described, and is too familiar to be

repeated. It is indeed magnificent - and he who could look upon such

a scene and not turn from it a better man, must truly have forgotten

his better elements. An area wide enough for the territory of a

nation lies beneath you like a picture, with the Hudson winding

through like an inlaid vein of silver. The steamboats were just

visible, and I cannot give you a better idea of them than is given in

the ludicrous remark of someone, that "they looked like shoes

with cigar's stuck in them". The sun rose, and excuse me if I

say much to my comfort; for although wrapped in my cloak, I was

chilled through. The first beams which streamed across the landscape,

looked like sprinklings of white; for at my elevation the hills all

sunk to a level, and I puzzled myself to account for the long

shadows. They soon diminished however, as the sun rose higher, and

the beauty of the scene became transcendent. The rich colours of the

"garniture of the earth" stole out and the hundred towns

within the range of the eye glittered like studded gems over the

scene. It looked like a distant Eden flooded with light.

The Cauterskill Falls, (I do not know the etymology) are a mile and

half from the hotel, by the foot path; by the carriage road it is

farther. We pursued the gradual descent through woods which seem to

have suffered only from the hand of ages. The way was exceedingly

rough, and the huge trees were knit together in every position as

decay or storm had left them. Is really a noble forest; fit for the

company it keeps, of glen and waterfall; and if I were disposed to

moralize as I sometimes do over the prostration of these kings of

inanimate nature, I know of no place where the text would be more

forcible. We pursued our way for about an hour, till without being

aware of its neighborhood, we stood nearly upon the brow of the

precipice; I cannot describe the effect. It makes a man feel like the

poor worm, or elevates him to sublimity in keeping with its own, as

his humility or his pride is uppermost. I felt both; for my

temperament is chameleon. |

|

|

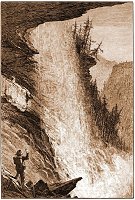

The glen of Cauterskill is probably half a stone's throw in width,

and two or three hundred feet in depth. It looks like, I scarce know

what - a huge well - a fearful chasm - a sinking of the earth to its

center - any thing that will give you an idea of depth made by

violence. There is no slope - but abrupt ragged perpendicular of

sides, appearing as if they had been rent asunder by an earthquake.

The rock over which the water pours projects far out of from its

base, somewhat in the shape of an umbrella; leaving a very

considerable area between it and the sheet of the fall. There is a

ledge about halfway up from the base, of the width of a mantelpiece

around which you can get, for it is neither walking nor creeping, but

a very ugly kind of hitch, not all comfortable, when coupled of the

danger of mingling with the "mighty waters" at the bottom.

Here, however, we perched ourselves, and clung long enough to get our

four shillings worth of the sublime; for this is the price the Miller

received for opening his sluice, that supplies the water for the

fall; though I must do myself justice to say that I forgot my four

shillings till the roar subsided. |

|

|

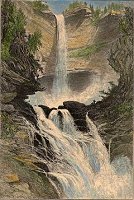

The quantity of water is very small, and in falling a hundred feet it

divides: into drops, and has a beautiful effect when seen from

behind. It pours immediately from the basin which receives it, over a

second fall about 80 ft., where, breaking repeatedly upon projecting

rocks before it reaches the bottom it assumes an appearance of most

wonderful sublimity and beauty. We went to the bottom, and looked up

both the falls. This is the perfection of the scene. You gaze up from

such depth along two sheets of water - one just above you, pouring

down its fearful path with the noise of a thunder peal, and another

beyond leaping from a projecting shelf which seems to you more like

an outlet of the clouds than an earthly level, - to look up and see

only a piece of the blue sky, and be walled in apparently by rocks

reaching up to it, it is awful. It is a place for man to fall down

and confess himself a worm. |

|