This story and illustrations

are from—

Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly—August, 1882

THE

COMFORTS AND DISCOMFORTS OF TRAVEL.

THE

COMFORTS AND DISCOMFORTS OF TRAVEL.

BY N. ROBINSON,

TRAVELING IS rendered so comfortable

nowadays that the slightest twinges of discomfort call forth "howling

commentaries on the text." Palace-cars by day—veritable

boudoirs on wheels—and sleeping-cars by night, have rendered

locomotion in this country so luxurious that distance has ceased

to appall and season to dismay. Our palatial steamers, too, contribute

their quota; while the baggage system removes the last, though

not the least, cause for anxiety from the mind of the sybaritic

traveler.

Traveling has, indeed, arrived at very

high condition of perfection, and each day witnesses some additional

rivet to our comforts. Our dining-cars, their bills of fare—worthy

of Delmonico or the Brunswick—render the dreaded rush to

the dreadful buffet unnecessary, while the connoisseur in wine

can have his champagne iced to as many degrees below zero as may

suit his critical palate, or his claret warmed to blood or fever

heat if he will. The system of ordering luncheon by telegraph,

too, is in keeping with this too too rapid age. It is satisfactory

to be enabled at, say Philadelphia, to select a piquant luncheon

from the menu, and to feel that it awaits your arrival at Wilmington—hot

or cold, as your Right Royal Highness may have been pleased to

command it.

Steamboat travel, especially river end

lake, is about as luxurious a mode of locomotion as can be by

any possibility conceived. The spacious saloons, the superb surroundings,

the gilding, the mirrors, the carvings, the carpets, the series

of decks (with their awnings in Summer), the restaurant, the staterooms!

Everything that ingenuity can suggest is pressed into the service

to render a trip by boat an episode to be immensely enjoyed, and

as gratefully remembered.

With the ocean steamer comes the terrible

monster, seasickness. Gildings and mirrors and tapestries go for

naught in the presence of this dreaded and remorseless fiend.

Like love, it levels all ranks low, and lays the sceptre by the

shepherd’s crook—or, in less poetical language, the

votive offering to Neptune of the millionaire beside that of the

bumble and impecunious emigrant. To those who do not suffer, the

ocean steamer is a floating palace, with lackeys and retainers

in the shape of sunkissed stewards. Electric-bells and saltwater-baths,

fresh fruit and new-laid eggs, are but so many items. Passengers

growl because a daily paper is denied them, and use full-flavored

language if the bill-of-fare is minus a single luxury for which

they may have a momentary craving.

Traveling nowadays is as much a necessity

as stopping at home used to be in the year one. Everybody travels—everybody

has been somewhere; and people who have only migrated, as in the

"Vicar of Wakefield," from the blue bedroom to the brown,

hang their heads for very shame that they have done so very little

in the way of locomotion.

Traveling has been made so easy that

it requires very little effort to set the wheels going. Packing

one’s impedimenta is now the severest portion of the entire

move. Once packed, the express does the rest. The fever of travel

comes upon society at stated periods; and travel, society must

and will at any cost. This fever assumes graver symptoms as the

seasons roll over, and the trip to the White Mountains in time

extends to the Yosemite Valley, or the spin over to Paris to a

dash into the Danubian Provinces. The thirst of travel needs to

be slaked, and native wine seldom possesses the necessary properties—the

rush is over the pond.

Of course, shore are still left a few

dignified, old-fashioned Old World people who on a certain day,

at a certain hour, move from the town to the country-house or

who make an annual excursion to visit a relative or friend. This

good old conservatism is being rapidly squeezed out through the

medium of the excursion-train and the excursion-steamer.

All the world goes upon excursion trips,

and no one returns without a fault to find or a grumble to growl.

Breathes there a man or woman who ever yet came back after a day’s

cheep junketing without a dismal catalogue of complaints ? Take

the excursion steamers. You arrive, though you rise with the lark,

to find the best places always occupied. Feelings of dire ill-will

permeate your bosom as you perceive half a dozen deck-chairs appropriated

by two persons, the feet of the lady on one extra, her impedimenta

upon another, while her male companion, with a diabolical artfulness,

engrosses a couple more, loading the unwary to believe that he

is but holding these forts for temporarily absent friends. The

crush on board the excursion-boat is the next feature—pitiful

in hideous discomfort. Ladies weighing 300 pounds and upward are

very good-natured and very amiable They patronize steamboat excursions

to an alarming extent. "You see," a confiding and intelligent

deckhand once observed to me, "they get on a couple o’

chairs and sit facie’ the breeze, en’ fens themselves

all the time, and nobody interferes with them nor nothin’.

They’re happy as clams at high water."

Children are in mundane Paradise on the

excursion steamer, and, wild with innocent joy, romp and push

and tear round till their elders wish them—at home. Then

there are the bores: the man who will talk politics, or

the prosy female who will discuss Sunday-school; the gentleman

who has just returned from Europe, and the lady whose height of

earthly ambition is to get there; the party who knows every inch

of the river or bay, and the nervous individual who informs you

of the exact place wherein to find the "best" life-preservers,

and speaks despondingly in reference to the dilapidated condition

of the boilers.

The effect of the sun playing down upon

your umbrella, assuming that you are provided with one, begets

a tortuous thirst. The ice-water has given out; the lager beer

is an infamy; the coffee–execrable; the tea–poison.

Champagne is expensive, and the red or the Rhine wine in the most

friendly relations with vinegar. You have brought your basket,

and feel peckish. You proceed to open this treasury of edibles

and to expose its toothsome contents. A hundred pair of wolfish

eyes are watching your every movement; one child nudges another,

and the electric whisper goes round. You are the centre of envious

glances; your immediate neighbors cordially detest you, and if

an occasion arrives for rendering you uncomfortable, depend upon

it that it will be utilized.

The food vended on board the excursion-steamer

is of the worst possible description, the caterers having not

one, but both eyes directed toward profit. Feverish from thirst

and fatigue, your eyelids aching, you return to the place from

whence you came, and register an inward vow never to be found

on the deck of an excursion-steamer again—a row broken with

commendable regularity.

How favorably the ordinary passenger-boat

compares with its cousin, the excursion! Everything is in order.

The employee polite and anxious, the viands excellent, the time

kept to the minute, the stateroom a model of cleanliness if not

of comfort. Take, for example, and as a type, the day-boat from

New York to Albany—one of the most delightful and picturesque

trips in the wide world. You go on board at 8:30, and make one

in the eight or nine hundred travelers who are en route to the

Catskills, Saratoga, Lake George, and heaven only knows where

besides. A joyous, bustling, expectant, excited, well-bred, fashionable

crowd buzzes about the decks. Old ladies, young ladies, middle-aged

ladies, and ladies of no particular age at all, attired in traveling

costumes of every conceivable sort, shape, size and description,

sit, stand, recline, lounge and lay upstairs and down-stairs (if

such unnautical expression be permitted), in blues braided with

white, whites bound in blue, browns trimmed with black, and blacks

scalloped with brown. Some carry nickel-bound bags, and embroidered

wraps like miniature bolster-cases; others are provided with quaint

early English pockets, deftly marked with their monograms, and

containing gossamer handkerchiefs fit but to brush an enormous

butterfly from the upturned nose of the Bleeping beauty in the

wood. Some wear linen dusters from chin to heel, until they look

as though attired for a sack-race Rae. Hats shades of Gainsborough

and Greuze I such grace, such elegance, such sweep, such chic,

such liveliness, such head-caressers! Rakish little dogs, some

of them with the leaf touching the bridge of the nose, or stuck

on the side with the bewitching abandon of Peg Woffington; others

worn as demurely as Clarissa Harlowe’s or flung back on the

neck, and depending for support upon a rosebud or a sprig of mignonette;

flowers so ripe and real as to induce roving bees and dissipated

flies to seek Barmecidal feasts thereon. Hair! Ye gods! black,

brown, chestnut, auburn, wine colored, red, yellow, and white;

in plaits, pig-tails, curls, corkscrews, bands,. kisses, Montagues,

shells, rolls, and every other form known to the advanced females

of this the fag end of the nineteenth century; pearl-powder, rouge,

cherry-paste, and burnt umber are fairly represented, and beauty-veils

at a discount.

Let us take a look at the men. Old dandies,

with dyed hair and aide-whiskers of that purple so fashionable

in Rome B.C. 500. Paterfamilias issuing orders in an authoritative

way, and glowing with the pride of " Here I am, with my household

gods, off to the best hotel at Saratoga I Look at me 1" Young

fellows with collared heads, in the loudest possible suits, and

nautical hats that would have won the heart of Black-eyed Susan,

attached to canes of enormous proportions, and sucking cheap cigars

or cheaper toothpicks, with an "I’ve just dined at Delmonico’s!"

air. Portly brokers in stiff white waistcoats, giving them all

the appearance of gazing over newly whitewashed walls.

Legislators, looking very profound, and

about as cheerful as Acts of Congress. Earnest middle-aged men

in spectacles and alpaca goats thirsting for information, and

deep in the mysteries of the guide-books. Languid swells in blue

suits, with striped stockings and patent-leather shoes, absorbed

in each other, and maintaining a masterly inactivity. Greasy men

in bulgy clothes, with diamond shirtstuds, chains enormous enough

to hang bales of cotton, and immense rings upon fat, hairy fingers,

surmounted by inky nails. A few provincials of the stage-Yankee

type, tourists whose glacial coldness, fixed eye-glasses, and

general imperturbability bespeak them Englishmen, arrayed in their

rhinoceros robes of insular prejudice. And, of course, just as

the gangway is about to be drawn aboard, the stereotyped elderly

lady is declared in sight, who stoutly refuses to " hurry

up," who thrusts her bandbox in the eye of the nearest deckhand

and her umbrella to back it up; who will not venture on the plank

until it is more securely fixed; who drops her umbrella, then

her reticule, then her spectacles, then all three, and refuses

point-blank to budge an inch until her property is restored to

her; and who is finally somewhat unceremoniously thrust forward

under indignant protests and threats of writing to the Herald.

A bright and brilliant sight greets us

as we ascend to the deck. The river is studded with craft of every

description, from the huge ocean steamer to the tiny sailing-boat,

from the richly laden and dignified argosy to the impudent little

tug, scooting hither and thither and audaciously darting beneath

the very bows of some leviathan, in momentary danger of being

crushed up like an eggshell. White-sailed sloops and schooners,

ferryboats speeding from shore to shore with their living and

anxious freight, canal-boats of enormous dimensions, great tows

of barges, the lazy life on which would seem like a Summer dream;

pleasure craft in saucy swiftness, their snowy canvas resembling

the outstretched wings of gigantic seabirds—all these, with

the teeming life on either shore, and the Palisades in the purple-blue

and hazy distance, tend to form an ensemble at once striking,

impressive, and to the memory imperishable.

Little groups soon form themselves in

coigne of vantage. The bows are extensively patronized, camp-stools

are in tremendous requisition, windlasses speedily utilized, and

coils of rope compelled a double debt to pry. Jaunty young gentlemen,

with a view to exhibit their intrepidity, sit loosely on the bulwarks,

allowing their feet to hang over the side of the

ship, to the admiration and dismay

of the young ladies. Very large cigars are smoked, and cheeks

grow pale that but an hour ago blushed, if not exactly in praise

of their own loveliness, possibly beneath the flushing influence

of the seductive cobbler. Jones, of Wall Street, poses as if for

his photograph; the position is painful, but Miss Bluepatch, of

Fifth Avenue, rewards him with a look wherein a smile is secretly

wrapped up, and he poses on to Poughkeepsie. Smith’s boots

are new, and just a leetle too small for him, and yet this

heroic fellow stands the whole way to West Point, expatiating

on the beauties of the scenery to Miss Mintsauce, who, happy girl,

is seated upon an icebox, utterly unconscious of the delicious

agonies of her afflicted admirer. We saw all this at a glance,

and we saw more than this.

In the remotest corners of the boat sits

the brand-new brides and bridegrooms. Angelina is attired in a

traveling costume composed expressly for the occasion by that

great artist, Worth—the Talleyrand of the toilet. The dress

is a veritable poem, and seems to caress the fair form like a

thing of life. It would take the condensed evidence of a dozen

French milliners to describe even the "goring," so it

is not for us to rush in where a modiste would fear to

tread. Edwin, too, is brand-new, from the gilt sole of his boot,

which betrays the fact of its never having been hitherto worn,

to the shiny felt hat, with the impress of the hatter’s thumb

still upon it, as glossy and bright as a new drugstore.

The grim, gaunt grandeur of the Palisades

serves to render the gaff, sheeny, dimpled hills around Tarrytown,

Nyack and Sleepy Hollow even more lovely, and bathed in a glowing

bath of golden light, an auriferous glory, such as won Dana for

the mighty Jove. We crane for a peep at Sunnyside—the home,

"made up of gable-ends and fall of angles and corners as

an old crooked hat"—of Washington Irving; the scene

of the loves of Ichabod, Katrina and the muscular Brom Brones,

whose daring impersonation of the headless horseman won for him

his pretty pouting bride. We picture Irving seated beneath the

spreading foliage, employed in thinking out some of his charming

creations, or engaged in gentle converse with a welcome guest—say

with the man of drooping eyelids waxed mustaches, who did not

then foresee that awful day when the French eagles would be trailed

in the bloody dust of Se;dan. Yea, Napoleon III. was once upon

a time a visitor at Sunnyside.

And on we speed past Tarrytown, with

its sad, sad story of treachery and treason, and Sing Sing, where

piteous and strained eyes watch us from behind prison bars, till

we enter the beautiful Highlands, to be confronted by the Dunderberg,

and the exquisite scenery of West Point. Passing through this

cleft in the mountains we throb onward till the Catskills dreamily

lift themselves on the left, and six o’clock finds us at

Albany, the cupola of the magnificent Capitol standing out in

wondrous and superb relief.

We have dined well—a conscientious

soup, a slice of striped base, a warm cutlet with green peas and

a broiled chicken; ice cream and a peach. This is the very essence

of luxurious traveling.

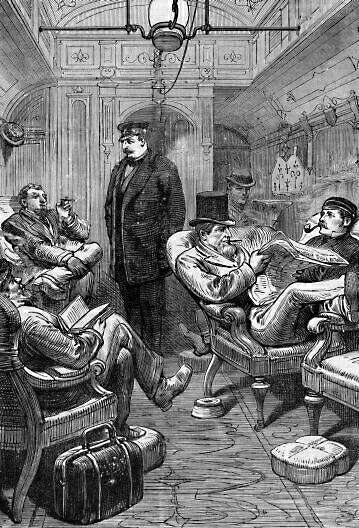

The palace-car

is a revelation to such of our cousins as venture across the pond.

Its size, its decorations, its lounges, its conveniences. Compare

it with the stuffy first-class carriage of British or Continental

travel, and how effete the latter article appears! The stiffness

of a compartment, be it upholstered in yellow plush or blue satin,

or Japanese silk, or Utrecht velvet, is to an American simply

appalling. His sense of freedom is deeply injured when he finds

himself deliberately locked into a prison on wheels. He cannot

stretch his limbs. Ice-water there is none. To bathe his temples

or flirt with his mustache through the medium of a mirror and

a comb is out of the question. The friendly and well posted conductor

is non est. There are no information-giving officials passing

through, no books presented or newspapers flung into his lap,

no candies or bananas, no cough-drops or cigars. He is dropped

into a seat, provided he can get one, with haughty and frozen-mannered

womankind and silent and abstracted men. If his luck be good he

may meet very pleasant, well-bred people; but then he must be

in luck, and fortune must be in a propitious mood. He is hemmed

in without even the luxury of a chance of stretching his limbs,

since the slightest movement in that direction might lead to the

disarrangement of the draperies of the opposite lady. If he is

the happy possessor of a newspaper, and offers it to his neighbor,

the chances are that the civility will be received with a frigid

" Thanks," and then he must endeavor to amuse himself

as best he may, cramped, with the uneasy feeling upon his mind

of being a prisoner until the train slows into a station, when

a muchly-bearded guard will politely but sternly inform him that

he must not descend, as the train will start in a "couple

o’ seconds, sir."

The palace-car

is a revelation to such of our cousins as venture across the pond.

Its size, its decorations, its lounges, its conveniences. Compare

it with the stuffy first-class carriage of British or Continental

travel, and how effete the latter article appears! The stiffness

of a compartment, be it upholstered in yellow plush or blue satin,

or Japanese silk, or Utrecht velvet, is to an American simply

appalling. His sense of freedom is deeply injured when he finds

himself deliberately locked into a prison on wheels. He cannot

stretch his limbs. Ice-water there is none. To bathe his temples

or flirt with his mustache through the medium of a mirror and

a comb is out of the question. The friendly and well posted conductor

is non est. There are no information-giving officials passing

through, no books presented or newspapers flung into his lap,

no candies or bananas, no cough-drops or cigars. He is dropped

into a seat, provided he can get one, with haughty and frozen-mannered

womankind and silent and abstracted men. If his luck be good he

may meet very pleasant, well-bred people; but then he must be

in luck, and fortune must be in a propitious mood. He is hemmed

in without even the luxury of a chance of stretching his limbs,

since the slightest movement in that direction might lead to the

disarrangement of the draperies of the opposite lady. If he is

the happy possessor of a newspaper, and offers it to his neighbor,

the chances are that the civility will be received with a frigid

" Thanks," and then he must endeavor to amuse himself

as best he may, cramped, with the uneasy feeling upon his mind

of being a prisoner until the train slows into a station, when

a muchly-bearded guard will politely but sternly inform him that

he must not descend, as the train will start in a "couple

o’ seconds, sir."

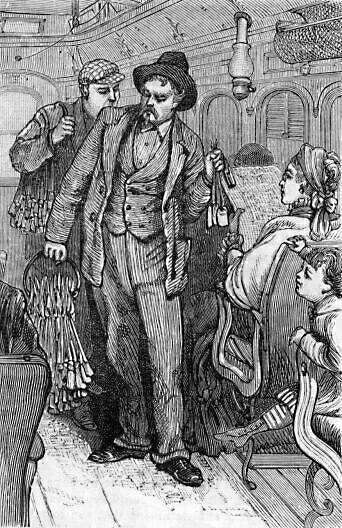

If the traveler is in need of refreshment

he must restrain the inner cravings until the train arrives at

a station possessing a refreshment counter. To this counter he

must plunge with the most frantic haste, to be snubbed by the

pretty, pert barmaids in attendance. If he is lucky enough to

secure a plate of soup he must swallow it in hot haste; if he

has annexed a portion of the carcass of a lean fowl, he is constrained

to recollect that fingers were constructed before knives and forks.

A bell rings the guard, bearded like a pard, growls something

in a hoarse and unintelligible voice, and the traveler, despoiled

of half a grown, for which he has in turn received a Barmecidal

feast, rushes back to the carriage, mistaking his compartment,

and finally, as the train is in motion, is bundled by the bearded

guard into his prison cell—flung over the foot of some gouty

countess, or into the arms of a spiteful elderly spinster, who

talks at him about American barbarians for the remainder

of the journey.

Arrived at his destination, instead of

quietly proceeding to his hotel, his baggage-check reposing in

his waistcoat pocket, he has to hustle and force his way into

a throng of eager, rude and excited people, all clamoring and

clambering for their luggage; all yelling at the porters, claiming

trunks and portmanteaus they had never laid eyes on before, while

the most acrobatic, disdaining the slow process of being waited

on by wooded headed employee, leap into the middle of the valice-laden

arena, and bear away in triumph their impedimenta—ay, and

not unfrequently the impedimenta of other people as well, for

this miserable baggage muddle is a rich mine to a certain class

of " gentlemen of the road. "

Our American, having by dint of "

skinning his eyes " and a leviathan bribe to a porter, at

last secured his baggage, beholds it flung on to the top of a

growler, alias a four-wheeler or a hansom, the fare being an unknown

quantity; or if he decline to ride in solitary grandeur, the hotel

omnibus is yawning to receive him—and still with a sense

of insecurity in regard to his luggage hanging over him like a

black cloud, he is driven to his hotel, again to worry and skirmish

over his trunks; nor is he happy until he beholds them deposited

in his bedroom.

How often during that fatiguing ride

has he longed for the short, sharp but welcome cry of " Baggage

checked! Want your baggage checked?" so significant of ease,

comfort, and security! How often has he yearned for a stretch

in the direction of the platform! How often has he wished for

a gossip with the ever-courteous and thoroughly posted conductor!

The nuisance of having books, periodicals and newspapers flung

into his lap every five minutes would have proved a boon, and

the crack of the shell of the homely peanut, delicious music.

The day-journey will be gotten through,

somehow or other.

"se the day weary, be the day long,

At last it ringeth to evensong.,"

Be the journey ever so dusty, ever so

hot, ever so tedious, the terminus at last comes in sight, and

should the American’s companions have proved unsociable or

worse, he has at least had the satisfaction of gazing out of the

windows, and of filling his eyes with "bits" of the

country as the iron horse sped upon its way. There are many distractions,

and pleasing ones, to boot, in a day journey, but at night—ye

gods!

Where, oh, where is the sleeping-car?

where is the ebony attendant, all smiles and white teeth? where

the cozy little smoking-compartment, where one can whiff the best

Henry Clay, and partake of a " modest quencher " in

the shape of a nightcap?

Our helpless

countryman is conveyed to an ill-lighted, fearfully stifling compartment,

containing eight divided seats, seven of which are already occupied.

A wheezy old lady refuses to have the window opened. The floor

is littered with handbags, wraps, etc., while the netting overhead

threatens to burst and brain the luckless individuals reposing

beneath it, a rap on the cranium from a heavy dressing-case being

somewhat dangerous in consequences. The American finds the netting

full, the floor packed. Where will he put his grip-sack, his hand-valise,

his "hard-shell" hat? He begs for a little space, addressing

a ghostly company in the dim religious light. Room is begrudgingly

doled to him with the remark, " These railway companies ought

to be ashamed of themselves, cramming people like sheep into their

beastly carriages!"

Our helpless

countryman is conveyed to an ill-lighted, fearfully stifling compartment,

containing eight divided seats, seven of which are already occupied.

A wheezy old lady refuses to have the window opened. The floor

is littered with handbags, wraps, etc., while the netting overhead

threatens to burst and brain the luckless individuals reposing

beneath it, a rap on the cranium from a heavy dressing-case being

somewhat dangerous in consequences. The American finds the netting

full, the floor packed. Where will he put his grip-sack, his hand-valise,

his "hard-shell" hat? He begs for a little space, addressing

a ghostly company in the dim religious light. Room is begrudgingly

doled to him with the remark, " These railway companies ought

to be ashamed of themselves, cramming people like sheep into their

beastly carriages!"

A dead silence falls upon the prisoners

as the black van moves out into the dark night. Sleep! Absurd!

Who could sleep seated in one position, the legs at a right angle,

the head being bumped against the dirty and fussy and musty wall-cushions?

Some one goes off—a loud snore proclaims that Sleep has taken

a scalp. A general snorting ensues. Bodies become limp and roll

to one side. The man or woman who but a few brief minutes before

would scarcely vouchsafe a reply to the disgusted American’s

query now lean upon him as though he were a brother. In vain he

nudges and fends them off; they return to their first love; they

are true as steel. Sleep! Oh, for that colored porter, and the

ice-water, and the stretch on the platform! Why, the curtained

lane between the berths would be scenery surpassing that so rapturously

described by Claude Melnotte, and the stockinged foot of the gentleman

in the upper berth a thing of beauty. Even the ordinary car, crammed

with passengers in every form of acrobatic position, were a paradise

on earth compared to the stifling first-class compartment on a

night-journey in Europe.

Some railway

companies in England have put on sleeping-cars, notably the "

Wild Irishman," between Holyhead and London, and the "

Scotch Limited Mail," from London to Edinburgh. In France,

too, there are sleeping oars between Paris and Bordeaux, and also

on two of the other lines; but to compare these, cars with a Pullman

or a Wagner would be equivalent to comparing a grocer’s wagon

to Mrs. Van Spuyten Dargole’s victoria. They are, however,

a move in the right but as yet the traveling public has not taken

to them, and while the first-class carriages will be full of suffering

humanity, the sleepers will have many berths to let.

Some railway

companies in England have put on sleeping-cars, notably the "

Wild Irishman," between Holyhead and London, and the "

Scotch Limited Mail," from London to Edinburgh. In France,

too, there are sleeping oars between Paris and Bordeaux, and also

on two of the other lines; but to compare these, cars with a Pullman

or a Wagner would be equivalent to comparing a grocer’s wagon

to Mrs. Van Spuyten Dargole’s victoria. They are, however,

a move in the right but as yet the traveling public has not taken

to them, and while the first-class carriages will be full of suffering

humanity, the sleepers will have many berths to let.

Diligence-traveling is rapidly dying

out, since mountains are being tunneled and the iron road laid

everywhere. The diligence for a mountain day trip is very delightful

traveling; for a night journey it is a horror. The discomforts

of the "good old coaching days," so rapturously referred

to by our grandfathers, are still preserved in diligence travel,

and a night in the wheezy, bone-setting, " leathern conveniency

" will live long in the memory. I have done two consecutive

nights in Mexico, sixteen mules being the team, the driver yelling

at the top of 0a lungs, his assistant pelting the leading files

with stones, and if I wasn’t as sore as Mickey Free’s

father, I know nothing of contusions, abrasions and partial dislocations.

I have crossed the Pyrenees from Perpignan to Gerona, To say that

I was stiff as the mummy of one of the Ptolemies at the end of

the journey is a close approximation to my condition. The Irish

jaunting-car is a delightful conveyance, and has to be experienced

in order to be appreciated. With a chosen companion, a good horse,

a cheerful driver, and a " drop o’ the crayture"

" in the well, the jaunting-car "bangs Banagher."

Many a glorious spin I have had on Killarney, through the wilds

of Connemara, and in the lovely valleys of Wicklow, and a more

agreeable mode of conveyance it is impossible to conceive. I would

never care to sit on a jaunting-car outside of "Ould Ireland,"

for, somehow or other, the vehicle seems to adapt itself to the

country and to the people. In Connemara and the West of Ireland

elongated jaunting-ears are run, each side capable of containing

from eight to ten passengers. They are worked with four horses,

usually garrons, or miserable animals, only fit for the

Knacker’s Yard, or the Corrida de Toros in sunny Spain. The

covered oar which confronts the American tourist at Queenstown

is a relic of the dark ages, and ought to have disappeared with

the sedan-chairs. An Irishman, upon being asked what was the difference

between an inside and an outside car, promptly replied:

" Shure, thin, the outside car has its wheels inside, an’

the inside car has its wheels outside."

The omnibuses of the world would form

a not uninteresting article. By far the most comfortable and most

elegant in my experience are those plying in Vienna—the horse-cars

also taking the palm. Paris, too, is admirably and comfortably

omnibused. The stages in this country are a little behind the

age. They are lumbrous, cumbrous vehicles, uncomfortable to the

last degree, and the system of packing people into them like figs

in a drum is as reprehensible as it is abominable.

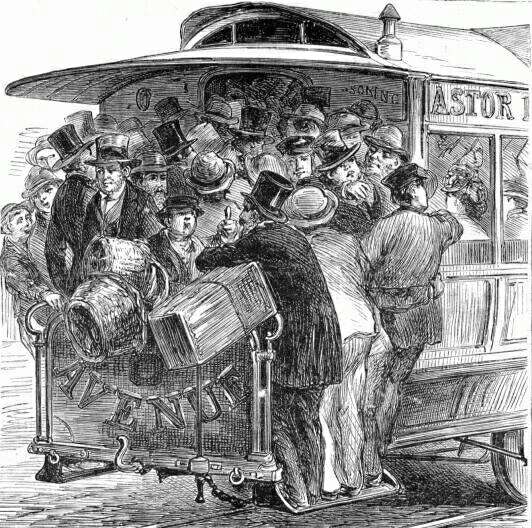

Our street-cars are eminently useful

and-that is all. There is little or no attempt at either comfort

or adornment, while in the principal cities of Europe the streetcar

is a perfect model of both. The vehicles are roomy, elegantly

gotten up, and exquisitely glean, while no overcrowding is permitted,

and every woman is sure of a seat. The conductors and drivers

wear uniforms, and are as presentable as Austrian Life-guardsmen.

With us the greater the load the greater the praise to driver

and conductor. The former is about as ragged and disreputable-looking

a personage as the heavy villain in the melodrama; the latter,

as a rule wears a uniform cap, sadly at variance with the remainder

of his raiment. Our illustration of the agonies of the rear platform

tells a piteous but o’er true tale. Fancy a lady having to

fight her way through that closely packed mass of perspiring humanity.

" How am I to get out ?" is the idea that weighs upon

the mind of some delicate woman during the entire ride. The conductor

is of no avail; he is powerless; and her chance of emancipation

lies in a stout heart and a pair of sharp elbows. The light-fingered

gentry approve highly of this system of packing street-cars especially

since the wearing of watches and jewelry has become so fashionable.

The basket nuisance in a street-car is one with which we are all

tolerably familiar.

There is a vast stride toward improvement

in the waiting-rooms of our large railway depots, and from being

great gloomy, depressing square ball-alleys, they are assuming

shape and color and form, with groined roofs, and paneled walls,

and stained-glass windows. As a natural sequence the country stations

will follow suit, and the waiting-room in the near future will

be a tasteful apartment, papered in perhaps—and why not ?—sunflowers,

with a dado and medieval window.

The great art-wave which is breaking

over this vast continent will not only beautify our abodes, but

our trysting-places as well, and the traveler will find the loss

of train or boat less painful, since he or she can wait for the

next that is to follow, in a room which will savor more of a humanized

habitation than of an enlarged cattle-pen.

There ought to be a large reward in store

for the noble being with mental capacity to organize some method

for ticket-checking once only. "Tickets ready!"

are words that raise feelings of no very amiable nature in the

breast of the ordinary traveler. To be wakened from a nap by an

implacable employe;, whose punch is pointed at your unoffending

head like a weapon of destruction, is, to say the least of it,

a singularly disagreeable sensation. To know that you carry about

your person that which may be called for at any moment, and must

be produced instanter, is a "turn on the nerves."

One is perpetually on the rack. Every time the door opens, every

appearance of a uniformed official, every stoppage of the train,

mentally sends the hand to the pocket-book for the be;te noir

that harasses from the commencement of the journey to the end;

and with what a sigh of relief one delivers up the punched and

tattered ticket for the last time! One feels inclined to give

the conductor something for himself for having taken it off one’s

hands. Something should be done, if possible, some system devised

by which the traveler will be relieved from this nightmare—one

punching at the beginning of the journey, when the ticket will

be taken up for good and all—and a boon will be conferred

on millions.

On the New York elevated railroads the

passengers, until a comparatively recent date, were compelled

to carry their tickets and deliver them up at the end of their

respective trips. So many mistakes occurred, and so much grumbling

arose, that now the ticket is dropped into a box while it is still

warm with the digital pressure of the delivery clerk. The system

works well, and millions are all the happier.

The days of the bobtail-car have been

too long in the land. It is an accommodation, but a nuisance.

The anguish of having one’s pet corns trample I upon while

a heavy man or woman wobbles to the change-window is too dreadful

to dwell upon. The jerk which sends the change flying all over

the car; the catapultic upheaval that flings the newcomer into

a seat or into the repelling arms of an already seated passenger;

the terrible anxiety when the bell rings, announcing a defaulter

lest you be suspected; the frownings and scowlings of the uncongenial-looking

driver as he counts his heads preparatory to pouncing upon the

assumed swindler; the dangers arising from the accumulation of

small boys on the steps—all these are the discomforts attaching

themselves to the " bobtail," and I say, "Away

with it."

One of the discomforts connection with

ocean travel is the Custom-house that grimly confronts you on

your arrival anywhere, everywhere You are as innocent as a lamb,

your hands are as clean as those of the Princess in the "Arabian

Nights, " who made the famous cheese. cakes. You have nothing

to declare, nothing dutiable, nothing but your immediate wearing

apparel; and yet, as in the case of the bell on the bobtail car,

the approach of the Custom-house officer causes an indefinable

thrill of apprehension.

Assuming, my dear madam, that you have

bought a seal skin sacque for a dear friend, or a couple of silk

dresses for your sisters or your cousins, are you not singularly

exercised as the grim official deliberately plunges his not always

savory hands amongst your delicate finery and nervous to the last

degree when he comes to disturb the articles in question? What

indignation and terror do you experience as he coldly informs

you that the dresses must be appraised, and what a flow of language

comes to your rosy lips in disparagement of articles which you

selected in Paris as being the most chic in the "Bon

Marche;" or in the Magazin du Louvre.

Here is a discomfort in travel that must

be done away with. No matter how innocent we may be, the thought

of the dreaded Custom house officer is a shadow upon the sunniest

and smoothest voyage.

It is, however, due to the Customs employee

to say that they do their spiriting very gently, and that they

meet with "hard cases", goes without saying; ladies

with elastic consciences and gentlemen without any consciences

at all. Their treatment, however, Or the ordinary passenger, subject

to the ordinary weaknesses of human nature, is, so far as official

nature will permit, highly considerate.

"Beautiful Snow" has been so

gracefully sung in song and story that it needs no rhapsodizing

here. A snowdrift in a deep cutting, blocking the track, may be

a thing of beauty, but it is scarcely a joy for ever. Nor is it

a comfortable feeling for the traveler by rail to hear torpedoes

exploding as the train rushes through a blinding, bewildering

snowstorm. Snow, save for sleighing purposes, is one of the discomforts

of travel. It disarranges the timetable, it breaks appointments,

it spoils dinner, it compels one to wear gum-shoes—it’s

a nuisance.

The heating of cars and bouts is a question

that demands a few words. As a rule, there is either too much

heat or too little. You are suffocated or you are shivering. Cold

is not so difficult to bear as heat, for you can warm yourself,

but to cool yourself is another matter. The thermometer is far

below freezing-point; the conductor of the car being a chilly

mortal himself, or being very good natured, resolves that the

passengers shall at all events have nothing to complain of on

the score of heat. He turns on all at his command, piles coal

into the stove, and in a few minutes comes the dry, suffocating

feel, that knows of no relief save one, that of flinging open

the window or door, and letting in a knife-like air that cuts

to the very marrow.

Of course!, there are some passengers

who partake of the nature of Salamander, for whom no heat is too

much, and who would flirt with the stove in the dog-days; but

the average passenger dislikes to be stifled or dry-baked, and

he undergoes both in a long Winter railway journey.

Some plan should be devised by which

our cars could be heated to a certain temperature, warm enough

to prove agreeable, yet not too warm. Let the Salamanders put

on overcoats and wraps, as is done in English railway carriages,

where they have no artificial heat at all save in the first-class,

where long jars covered with flannel and filled with hot water

are placed beneath your feet at certain stations along the line.

That feeling of asphyxiation that one endures, consequent upon

the overheating of the cars, is about the most unendurable one

can experience. The flushed cheek, the pink hand, the incipient

headache, the unquenchable thirst, all arise from an overdose

of heat, and the entire pleasure of a trip is completely marred

either through the carelessness or extravagance of a thoughtless

conductor.

There is one feature in connection with

the comforts and discomforts of travel that should not be passed

over, and that is the knack some people possess for making themselves

comfortable, and, vice versa. Persons of the Mark Tapley class

enjoy travel under every circumstance, and to this class of the

community at large I make my most deferential bow.

Stories Page | Contents

Page