The Century Magazine

May, 1888 - October, 1888

The Locomotive Chase in Georgia

(Story of the “General”)

by William Pittenger,

Author of “Daring and Suffering” and a member of the

Raiding Party

THE railroad raid to Georgia, in the spring of 1862, has always

been considered to rank high among the striking and novel incidents

of the civil war. At that time General O. M. Mitchel, under whose

authority it was organized, commanded Union forces in middle Tennessee,

consisting of a division of Buell's army. The Confederates were

concentrating at Corinth, Mississippi, and Grant and Buell were

advancing by different routes towards that point. Mitchel's orders

required him to protect Nashville and the country around, but

allowed him great latitude in the disposition of his division,

which, with detachments and garrisons, numbered nearly seventeen

thousand men. His attention had long been strongly turned towards

the liberation of east Tennessee, which he knew that President

Lincoln also earnestly desired, and which would, if achieved,

strike a most damaging blow at the resources of the rebellion.

A Union army once in possession of east Tennessee would have the

inestimable advantage, found nowhere else in the South, of operating

in the midst of a friendly population, and having at hand abundant

supplies of all kinds. Mitchel had no reason to believe that Corinth

would detain the Union armies much longer than Fort Donelson had

done, and was satisfied that as soon as that position had been

captured the next movement would be eastward towards Chattanooga,

thus throwing his own division in advance. He determined, therefore,

to press into the heart of the enemy's country as far as possible,

occupying strategical points before they were adequately defended

and assured of speedy and powerful renforcement. To this end his

measures were vigorous and well chosen.

On the 8th of April, 1862,— the day after the battle of

Pittsburg Landing, of which, however, Mitchel had received no

intelligence, — he marched swiftly southward from Shelbyville

and seized Huntsville, in Alabama, on the 11th of April, and then

sent a detachment westward over the Memphis and Charleston Railroad

to open railway communication with the Union army at Pittsburg

Landing. Another detachment, commanded by Mitchel in person, advanced

on the same day seventy miles by rail directly into the enemy’s

territory, arriving unchecked with two thousand men within thirty

miles of Chattanooga,— in two hours' time he could now reach

that point, — the most important position in the West. Why

did he not go on? The story of the railroad raid is the answer.

The night before breaking camp at Shelbyville, Mitchel sent an

expedition secretly into the heart of Georgia to cut the railroad

communications of Chattanooga to the south and east. The fortune

of this attempt had a most important bearing upon his movements,

and will now be narrated.

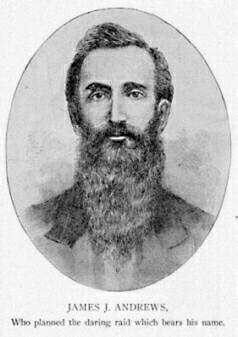

In the employ of General Buell was a spy named James J. Andrews,

who had rendered valuable services in the first year of the war,

and had secured the full confidence of the Union commanders. In

March, 1862, Buell had sent him secretly with eight men to burn

the bridges west of Chattanooga; but the failure of expected cooperation

defeated the plan, and Andrews, after visiting Atlanta and inspecting

the whole of the enemy's lines in that vicinity and northward,

had returned, ambitious to make another attempt. His plans for

the second raid were submitted to Mitchel, and on the eve of the

movement from Shelbyville to Huntsville Mitchel authorized him

to take twenty-four men, secretly enter the enemy's territory,

and, by means of capturing a train, burn the bridges on the northern

part of the Georgia State Railroad and also one on the East Tennessee

Railroad where it approaches the Georgia State line, thus completely

isolating Chattanooga, which was virtually ungarrisoned.

The soldiers for this expedition, of whom the writer was one,

were selected from the three Ohio regiments belonging to General

J. W. Sill's brigade, being simply told that they were wanted

for secret and very dangerous service. So far as known, not a

man chosen declined the perilous honor. Our uniforms were exchanged

for ordinary Southern dress, and all arms except revolvers were

left in camp. On the 7th of April, by the roadside about a mile

east of Shelbyville, in the late evening twilight, we met our

leader. Taking us a little way from the road, he quietly placed

before us the outlines of the romantic and adventurous plan, which

was: to break into small detachments of three or four, journey

eastward into the Cumberland Mountains, then work southward, traveling

by rail after we were well within the Confederate lines, and finally,

the evening of the third day after the start, meet Andrews at

Marietta, Georgia, more than two hundred miles away. When questioned,

we were to profess ourselves Kentuckians going to join the Southern

army.

On the journey we were a good deal annoyed by the swollen streams

and the muddy roads consequent on three days of almost ceaseless

rain. Andrews was led to believe that Mitchel's column would be

inevitably delayed; and as we were expected to destroy the bridges

the very day that Huntsville was entered, he took the responsibility

of sending word to our different groups that our attempt would

be postponed one day — from Friday to Saturday, April 12.

This was a natural but a most lamentable error of judgment.

One of the men detailed was belated and did not join us at

all. Two others were very soon captured by the enemy; and though

their true character was not detected, they were forced into the

Southern army, and two reached Marietta, but failed to report

at the rendezvous. Thus, when we assembled very early in the morning

in Andrews's room at the Marietta Hotel for final consultation

before the blow was struck we were but twenty, including our leader.

All preliminary difficulties had been easily overcome and we were

in good spirits. But some serious obstacles had been revealed

on our ride from Chattanooga to Marietta the previous evening.

*( The different detachments reached the Georgia State Railroad

at Chattanooga, and traveled as ordinary passengers on trains

running southward. EDITOR). The railroad was found to be crowded

with trains, and many soldiers were among the passengers. Then

the station — Big Shanty — at which the capture was

to be effected had recently been made a Confederate camp. To succeed

in our enterprise it would be necessary first to capture the engine

in a guarded camp with soldiers standing around as spectators,

and then to run it from one to two hundred miles through the enemy's

country, and to deceive or overpower all trains that should be

met — a large contract for twenty men. Some of our party

thought the chances of success so slight, under existing circumstances,

that they urged the abandonment of the whole enterprise. But Andrews

declared his purpose to succeed or die, offering to each man,

however, the privilege of withdrawing from the attempt —

an offer no one was in the least disposed to accept. Final instructions

were then given, and we hurried to the ticket office in time for

the northward bound mail-train, and purchased tickets for different

stations along the line in the direction of Chattanooga.

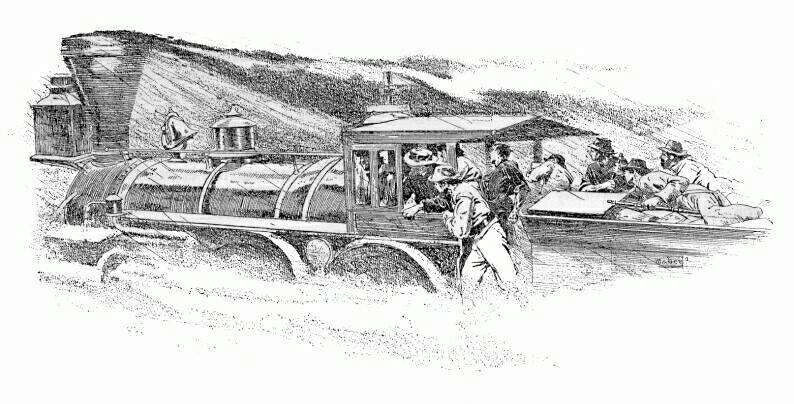

Our ride, as passengers, was but eight miles. We swept swiftly

around the base of Kenesaw Mountain, and soon saw the tents of

the Confederate forces camped at Big Shanty gleam white in the

morning mist. Here we were to stop for breakfast and attempt the

seizure of the train. The morning was raw and gloomy, and a rain,

which fell all day, had already begun. It was a painfully thrilling

moment. We were but twenty, with an army about us, and along and

difficult road before us, crowded with enemies. In an instant

we were to throw off the disguise which had been our only protection,

and trust our leader's genius and our own efforts for safety and

success. Fortunately we had no time for giving way to reflections

and conjectures which could only unfit us for the stern task ahead.

When we stopped, the conductor, the engineer, and many of the

passengers hurried to breakfast, leaving the train unguarded.

Now was the moment of action. Ascertaining that there was nothing

to prevent a rapid start, Andrews, our two engineers, Brown and

Knight, and the fireman hurried forward, uncoupling a section

of the train consisting of three empty baggage or box-cars, the

locomotive, and the tender. The engineers and the fireman sprang

into the cab of the engine, while Andrews, with hand on the rail

and foot on the step, waited to see that the remainder of the

party had gained entrance into the rear box-car. This seemed difficult

and slow, though it really consumed but a few seconds, for the

car stood on a considerable bank, and the first who came were

pitched in by their comrades, while these in turn dragged in the

others, and the door was instantly closed. A sentinel, with musket

in hand, stood not a dozen feet from the engine, watching the

whole proceeding; but before he or any of the soldiers or guards

around could make up their minds to interfere all was done, and

Andrews, with a nod to his engineer, stepped on board. The valve

was pulled wide open, and for a moment the wheels slipped round

in rapid, ineffective revolutions; then, with a bound that jerked

the soldiers in the box-car from their feet, the little train

darted away, leaving the camp and the station in the wildest uproar

and confusion. The first step of the enterprise was triumphantly

accomplished.

According to the time-table, of which Andrews had secured a

copy, there were two trains to be met. These presented no serious

hindrance to our attaining high speed, for we could tell just

where to expect them. There was also a local freight not down

on the timetable, but which could not be far distant. Any danger

of collision with it could be avoided by running according to

the schedule of the captured train until it was passed; then at

the highest possible speed we could run to the Oostenaula and

Chickamauga bridges, lay them in ashes, and pass on through Chattanooga

to Mitchel, at Huntsville, or wherever eastward of that point

he might be found, arriving long before the close of the day.

It was a brilliant prospect, and so far as human estimates can

determine it would have been realized had the day been Friday

instead of Saturday. On Friday every train had been on time, the

day dry, and the road in perfect order. Now the road was in disorder,

every train far behind time, and two “extras” were approaching

us. But of these unfavorable conditions we knew nothing, and pressed

confidently forward.

We stopped frequently, and at one point tore up the track,

cut telegraph wires, and loaded on cross-ties to be used in bridge

burning. Wood and water were taken without difficulty, Andrews

very coolly telling the story to which he adhered throughout the

rim, namely, that he was one of General Beauregard's officers,

running an impressed powder train through to that commander at

Corinth. We had no good instruments for track-raising, as we had

intended rather to depend upon fire; but the amount of time spent

in taking up a rail was not material at this stage of our journey,

as we easily kept on the time of our captured train. There was

a wonderful exhilaration in passing swiftly by towns and stations

through the heart of an enemy's country in this manner. It possessed

just enough of the spice of danger, in this part of the run, to

render it thoroughly enjoyable. The slightest accident to our

engine, however, or a miscarriage in any part of our programme,

would have completely changed the conditions.

At Etowah we found the “Yonah,” an old locomotive

owned by an iron company, standing with steam up; but not wishing

to alarm the enemy till the local freight had been safely met,

we left it unharmed. Kingston, thirty miles from the starting-point,

was safely reached. A train from Rome, Georgia, on a branch road,

had just arrived and was waiting for the morning mail — our

train. We learned that the local freight would soon come also,

and, taking the side-track, waited for it. When it arrived, however,

Andrews saw, to his surprise and chagrin, that it bore a red flag,

indicating another train not far behind. Stepping over to the

conductor, he boldly asked “What does it mean that the road

is blocked in this manner when I have orders to take this powder

to Beauregard without a minute’s delay ?” The answer

was interesting but not reassuring: “Mitchel has captured

Huntsville and is said to be coming to Chattanooga, and we are

getting everything out of there.” He was asked by Andrews

to pull his train a long way down the track out of the way, and

promptly obeyed.

It seemed an exceedingly long time before the expected “extra”

arrived, and when it did come it bore another red flag. The reason

given was that the “local,” being too great for one

engine, had been made up in two sections, and the second section

would doubtless be along in a short time. This was terribly vexatious;

yet there seemed nothing to do but to wait. To start out between

the sections of an extra train would be to court destruction.

There were already three trains around us, and their many passengers

and others were all growing very curious about the mysterious

train, manned by strangers, which had arrived on the time of the

morning mail. For an hour and five minutes from the time of arrival

at Kingston we remained in this most critical position. The sixteen

of us who were shut up tightly in a box-car, — impersonating

Beauregard's ammunition, — hearing sounds outside, but unable

to distinguish words, had perhaps the most trying position. Andrews

sent us, by one of the engineers, a cautious warning to be ready

to fight in case the uneasiness of the crowd around led them to

make any investigation, while he himself kept near the station

to prevent the sending off of any alarming telegram. So intolerable

was our suspense, that the order for a deadly conflict would have

been felt as a relief. But the assurance of Andrews quieted the

crowd until the whistle of the expected train from the north was

heard; then, as it glided up to the depot, past the end of our

side-track, we were off without more words.

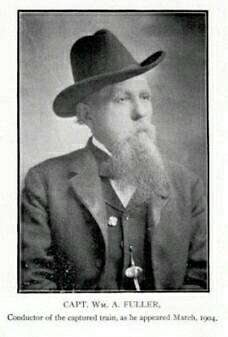

But unexpected danger had arisen behind us. Out of the panic

at Big Shanty two men emerged, determined, if possible, to foil

the unknown captors of their train. There was no telegraph station,

and no locomotive at hand with which to follow; but the conductor

of the train, W. A. Fuller, and Anthony Murphy, foreman of the

Atlanta railway machine shops, who happened to be on board of

Fuller's train, started on foot after us as hard as they could

run. Finding a hand-car they mounted it and pushed forward till

they neared Etowah, where they ran on the break we had made in

the road and were precipitated down the embankment into the ditch.

Continuing with more caution, they reached Etowah and found the

“Yonah,” which was at once pressed into service, loaded

with soldiers who were at hand, and hurried with flying wheels

towards Kingston. Fuller prepared to fight at that point, for

he knew of the tangle of extra trains, and of the lateness of

the regular trains, and did not think we should be able to pass.

We had been gone only four minutes when he arrived and found himself

stopped by three long, heavy trains of cars, headed in the wrong

direction. To move them out of the way so as to pass would cause

a delay he was little inclined to afford — would, indeed,

have almost certainly given us the victory. So, abandoning his

engine, he with Murphy ran across to the Rome train, and, uncoupling

the engine and one car, pushed forward with about forty armed

men. As the Rome branch connected with the main road above the

depot, he encountered no hindrance, and it was now a fair race.

We were not many minutes ahead.

Four miles from Kingston we again stopped and cut the telegraph.

While trying to take up a rail at this point we were greatly startled.

One end of the rail was loosened, and eight of us were pulling

at it, when in the distance we distinctly heard the whistle of

a pursuing engine. With a frantic effort we broke the rail, and

all tumbled over the embankment with the effort. We moved on,

and at Adairsville we found a mixed train (freight and passenger)

waiting, but there was an express on the road that had not yet

arrived. We could afford no more delay, and set out for the next

station, Calhoun, at terrible speed, hoping to reach that point

before the express, which was behind time, should arrive. The

nine miles which we had to travel were left behind in less than

the same number of minutes. The express was just pulling out,

but, hearing our whistle, backed before us until we were able

to take the side-track. It stopped, however, in such a manner

as completely to close up the other end of the switch. The two

trains, side by side, almost touched each other, and our precipitate

arrival caused natural suspicion. Many searching questions were

asked, which had to be answered before we could get the opportunity

of proceeding. We in the box-car could bear the altercation, and

were almost sure that a fight would be necessary before the conductor

would consent to “pull up” in order to let us out. Here

again our position was most critical, for the pursuers were rapidly

approaching.

Fuller and Murphy saw the obstruction of the broken rail in

time, by reversing their engine, to prevent wreck; but the hindrance

was for the present insuperable. Leaving all their men behind,

they started for a second foot-race. Before they had gone far

they met the train we had passed at Adairsville, and turned it

back after us. At Adairsville they dropped the cars, and with

locomotive and tender loaded with armed men, they drove forward

at the highest speed possible. They knew that we were not many

minutes ahead, and trusted to overhaul us before the express train

could be safely passed.

But Andrews had told the powder story again with all his skill,

and added a direct request in peremptory form to have the way

opened before him, which the Confederate conductor did not see

fit to resist; and just before the pursuers arrived at Calhoun

we were again under way. Stopping once more to cut wires and tear

up the track, we felt a thrill of exhilaration to which we had

long been strangers. The track was now clear before us to Chattanooga;

and even west of that city we had good reason to believe that

we should find no other train in the way till we had reached Mitchel's

lines. If one rail could now be lifted we would be in a few minutes

at the Oostenaula bridge; and that burned, the rest of the task

would be little more than simple manual labor, with the enemy

absolutely powerless. We worked with a will.

But in a moment the tables were turned. Not far behind we heard

the scream of a locomotive bearing down upon us at lightning speed.

The men on board were in plain sight and well armed. Two minutes

— perhaps one — would have removed the rail at which

we were toiling; then the game would have been in our own hands,

for there was no other locomotive beyond that could be turned

back after us. But the most desperate efforts were in vain. The

rail was simply bent, and we hurried to our engine and darted

away, while remorselessly after us thundered the enemy.

Now the contestants were in clear view, and a race followed

unparalleled in the annals of war. Wishing to gain a little time

for the burning of the Oostenaula bridge, we dropped one car,

and, shortly after, another; but they were “picked up”

and pushed ahead to Resaca. We were obliged to run over the high

trestles and covered bridge at that point without a pause. This

was the first failure in the work assigned us.

The Confederates could not overtake and stop us on the road;

but their aim was to keep close behind, so that we might not be

able to damage the road or take in wood or water. In the former

they succeeded, but not in the latter. Both engines were put at

the highest rate of speed. We were obliged to cut the wire after

every station passed, in order that an alarm might not be sent

ahead; and we constantly strove to throw our pursuers off the

track, or to obstruct the road permanently in some way, so that

we might be able to burn the Chickamauga bridges, still ahead.

The chances seemed good that Fuller and Murphy would be wrecked.

We broke out the end of our last box-car and dropped cross-ties

on the track as we ran, thus checking their progress and getting

far enough ahead to take in wood and water at two separate stations.

Several times we almost lifted a rail, but each time the coming

of the Confederates within rifle range compelled us to desist

and speed on. Our worst hindrance was the rain. The previous day

(Friday) had been clear, with a high wind, and on such a day fire

would have been easily and tremendously effective. But to-day

a bridge could be burned only with abundance of fuel and careful

nursing.

Thus we sped on, mile after mile, in this fearful chase, round

curves and past stations in seemingly endless perspective. Whenever

we lost sight of the enemy beyond a curve, we hoped that some

of our obstructions had been effective in throwing him from the

track, and that we should see him no more; but at each long reach

backward the smoke was again seen, and the shrill whistle was

like the scream of a bird of prey. The time could not have been

so very long, for the terrible speed was rapidly devouring the

distance; but with our nerves strained to the highest tension

each minute seemed an hour. On several occasions the escape of

the enemy from wreck was little less than miraculous. At one point

a rail was placed across the track on a curve so skillfully that

it was not seen till the train ran upon it at full speed. Fuller

says that they were terribly jolted, and seemed to bounce altogether

from the track, but lighted on the rails in safety. Some of the

Confederates wished to leave a train which was driven at such

a reckless rate, but their wishes were not gratified.

Before reaching Dalton we urged Andrews to turn and attack

the enemy, laying an ambush so as to get into close quarters,

that our revolvers might be on equal terms with their guns. I

have little doubt that if this had been carried out it would have

succeeded. But either because he thought the chance of wrecking

or obstructing the enemy still good, or feared that the country

ahead had been alarmed by a telegram around the Confederacy by

the way of Richmond — Andrews merely gave the plan his sanction

without making any attempt to carry it into execution.

Dalton was passed without difficulty, and beyond we stopped

again to cut wires and to obstruct the track. It happened that

a regiment was encamped not a hundred yards away, but they did

not molest us. Fuller had written a dispatch to Chattanooga, and

dropped a man with orders to have it forwarded instantly, while

he pushed on to save the bridges. Part of the message got through

and created a wild panic in Chattanooga, although it did not materially

influence our fortunes. Our supply of fuel was now very short,

and without getting rid of our pursuers long enough to take in

more, it was evident that we could not run as far as Chattanooga.

While cutting the wire we made an attempt to get up another

rail; but the enemy, as usual, were too quick for us. We had no

tool for this purpose except a wedge-pointed iron bar. Two or

three bent iron claws for pulling out spikes would have given

us such incontestable superiority that, down to almost the last

of our run, we should have been able to escape and even to burn

all the Chickamauga bridges. But it had not been our intention

to rely on this mode of obstruction — an emergency only rendered

necessary by our unexpected delay and the pouring rain.

We made no attempt to damage the long tunnel north of Dalton,

as our enemies had greatly dreaded. The last hope of the raid

was now staked upon an effort of a different kind from any that

we had yet made, but which, if successful, would still enable

us to destroy the bridges nearest Chattanooga. But, on the other

hand, its failure would terminate the chase. Life and success

were put upon one throw.

A few more obstructions were dropped on the track, and our

own speed increased so that we soon forged a considerable distance

ahead. The side and end boards of the last car were torn into

shreds, all available fuel was piled upon it, and blazing brands

were brought back from the engine. By the time we approached a

long, covered bridge a fire in the car was fairly started. We

uncoupled it in the middle of the bridge, and with painful suspense

waited the issue. Oh for a few minutes till the work of conflagration

was fairly begun! There was still steam pressure enough in our

boiler to carry us to the next wood-yard, where we could have

replenished our fuel by force, if necessary, so as to run as near

to Chattanooga as was deemed prudent. We did not know of the telegraph

message which the pursuers had sent ahead. But, alas! the minutes

were not given. Before the bridge was extensively fired the enemy

was upon us, and we moved slowly onward, looking back to see what

they would do next. We had not long to conjecture. The Confederates

pushed right into the smoke, and drove the burning car before

them to the next side-track.

With no car left, and no fuel, the last scrap having been thrown

into the engine or upon the burning car, and with no obstruction

to drop on the track, our situation was indeed desperate. A few

minutes only remained until our steed of iron which had so well

served us would be powerless.

But it might still be possible to save ourselves. If we left

the train in a body, and, taking a direct course towards the Union

lines, hurried over the mountains at right angles with their course,

we could not, from the nature of the country, be followed by cavalry,

and could easily travel — athletic young men as we were,

and fleeing for life — as rapidly as any pursuers. There

was no telegraph in the mountainous districts west and north-west

of us, and the prospect of reaching the Union lines seemed to

me then, and has always since seemed, very fair. Confederate pursuers

with whom I have since conversed freely have agreed on two points

— that we could have escaped in the manner here pointed out,

and that an attack on the pursuing train would likely have been

successful. But Andrews thought otherwise, at least in relation

to the former plan, and ordered us to jump from the locomotive

one by one, and, dispersing in the woods, each endeavor to save

himself. Thus ended the Andrews railroad raid.

It is easy now to understand why Mitchel paused thirty miles

west of Chattanooga. The Andrews raiders had been forced to stop

eighteen miles south of the same town, and no flying train met

him with the expected tidings that all railroad communications

of Chattanooga were destroyed, and that the town was in a panic

and undefended. He dared advance no farther without heavy renforcements

from Pittsburg Landing or the north; and he probably believed

to the day of his death, six months later, that the whole Andrews

party had perished without accomplishing anything.

A few words will give the sequel to this remarkable enterprise.

There was great excitement in Chattanooga and in the whole of

the surrounding Confederate territory for scores of miles. The

hunt for the fugitive raiders was prompt, energetic, and completely

successful. Ignorant of the country, disorganized, and far from

the Union lines, they strove in vain to escape. Several were captured

the same day on which they left the cars, and all but two within

a week. Even these two were overtaken and brought back when they

supposed that they were virtually out of danger. Two of those

who had failed to be on the train were identified and added to

the band of prisoners.

Now follows the saddest part of the story. Being in citizens'

dress within an enemy's lines, the whole party were held as spies

and closely and vigorously guarded. A court-martial was convened,

and the leader and seven others out of the twenty-two were condemned

and executed.* The remainder were never brought to trial, probably

because of the advance of Union forces and the consequent confusion

into which the affairs of the Departments of East Tennessee and

Georgia were thrown. Of the remaining fourteen, eight succeeded

by a bold effort — attacking their guard in broad daylight

— in making their escape from Atlanta, Georgia, and ultimately

in reaching the North. The other six who shared in this effort,

but were recaptured, remained prisoners until the latter part

of March, 1863, when they were exchanged through a special arrangement

made with Secretary Stanton. All the survivors of this expedition

received medals and promotion. The pursuers also received expressions

of gratitude from their fellow-Confederates, notably from the

governor and the legislature of Georgia.

* Below is a list of the participants in the raid:

Executed

James J. Andrews, leader;

William Campbell, a civilian who volunteered to accompany the

raiders;

George D. Wilson, Company B, 2d Ohio Volunteers;

Marion A. Ross, Company A, 2d Ohio Volunteers;

Perry G. Shadrack, Company K, 2d Ohio Volunteers;

Samuel Slavens, 33d Ohio Volunteers;

Samuel Robinson, Company G, 33d Ohio Volunteers;

John Scott, Company K, 21st Ohio Volunteers;

Escaped

Wilson W. Brown, Company F, 21st Ohio Volunteers;

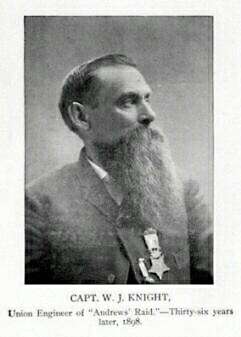

William Knight, Company E, 21st Ohio Volunteers;

Mark Wood, Company C, 21st Ohio Volunteers;

James A. Wilson, Company C, 21st Ohio Volunteers;

John Wollam, Company C, 33d Ohio Volunteers;

D. A. Dorsey, Company H, 33d Ohio Volunteers;

J. R. Porter, Company C, 21st Ohio, and Martin J. Hawkins, Company

A, 33d Ohio, reached Marietta, but did not get on

board of the train. They were captured and imprisoned with their

comrades.- EDITOR.

Exchanged

Jacob Parrott, Company K, 33d Ohio Volunteers;

Robert Buffam, Company H, 21st Ohio Volunteers;

William Bensinger, Company G, 21St Ohio Volunteers;

William Reddick, Company B, 33d Ohio Volunteers;

E. H. Mason, Company K, 21St Ohio Volunteers;

William Pittenger, Company G, 2d Ohio Volunteers.

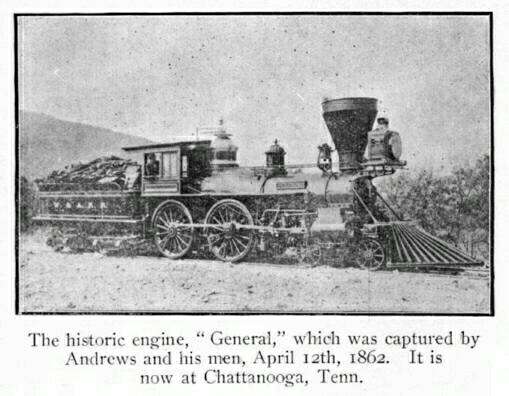

Some rather rare photographs

and Illustration—

Stories Page | Contents Page