|

INCLINED PLANES.

ONE of the subjects which attracted much attention at the outset

was inclined planes, and the extent to which they should be avoided

or adopted. As the primitive locomotives possessed very limited

power as hill-climbers, and were mere pigmies in contrast with

their successors in size and capacity, it seemed at one time to

be absolutely necessary that railways intended to traverse mountainous

countries over routes which necessitated heavy grades should be

supplemented by inclined planes, on which stationary engines would

furnish the motive power. It was in accordance with this idea

that some of the earliest coal railways, and especially the Delaware

and Hudson, were supplied with inclined planes, and that such

adjuncts were originally provided at both ends of the Philadelphia

and Columbia Railroad, and on the Portage Railroad. It should

be remembered that each of the important improvements in locomotives

that helped to increase their power to ascend steep grades diminished

the necessity for inclined planes.

As the Portage Railroad was used to cross the summits of the

Allegheny mountains, it was the most important undertaking of

the kind in this country, and in the world, at the period of its

construction. Of this road Mr. Solomon W. Roberts says: "There

were eleven levels, so called, or rather grade lines, and ten

inclined planes, on the Portage, the whole length of the road

being 36.39 miles. The planes were numbered eastwardly from Johnstown,

and the ascent from that place to the summit was 1,171.58 feet

in 26.59 miles, and the descent from the summit to Hollidaysburg

was 1,398.71 feet in 10.10 miles."

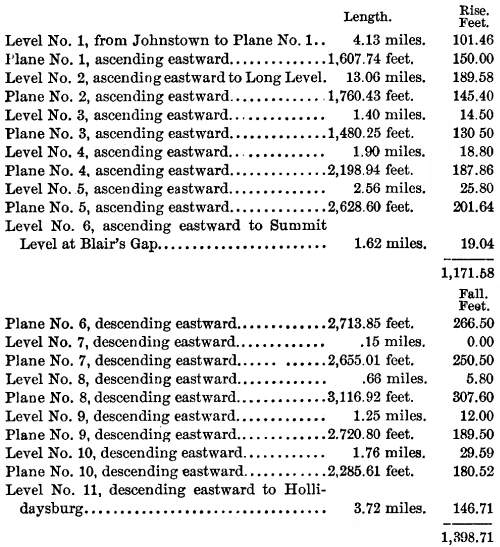

The planes were all straight, and their lengths and elevations,

together with the length of the grade lines or levels, which were

worked first by horse power, and subsequently by locomotives,

are stated in the following table:—

STATIONARY ENGINES VS. LOCOMOTIVES.

STATIONARY ENGINES VS. LOCOMOTIVES.

In regard to the economic considerations involved in the use

of inclined planes and stationary engines, Jonathan Knight, said

in 1832: "So recently as the beginning of the year 1829,

the relative economy of the stationary and locomotive systems,

upon level railways, or upon those but slightly inclined, was

warmly contested in England, and the question was not put to rest

until the recent improvements in the locomotive engine took place."

He added that on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, after the

improved engines (of Stephenson) were used, it was found that

"the expense per ton per mile, by these engines, will be

.164 of a penny, and by the stationary system .269 of a penny."

Knight estimated in 1832 that in this country it was probable

"that an engine, capable of conveying 30 tons of freight

120 miles in a day, will cost, including interest, repairs, renewals,

engineering attendance, and fuel, from $9 to $15 per day, according

to the price of fuel at the place demanded; and the cost per ton

per mile, in the one case, will be ¼ of a cent, and in

the other something less than ½ of a cent—more exactly

.417 of a cent." In brief, as locomotives were improved the

utility of inclined planes diminished.

The necessity of overcoming heavy grades by some methods is

so imperative in all the mountainous portions of this country

that the field of railway usefulness, and the limitations to the

speed and cheapness of railway movements, would have been greatly

restricted if the power of locomotives to draw relatively heavy

loads over steep grades had not been greatly increased by American

expedients and invention.

The nature of the delays and increase of expenditures caused

by the enforced use of inclined planes may be inferred from the

statement of Mr. Solomon W. Roberts that, on the Portage Railroad,

"at the head of each plane were two engines, of about thirty-five-horse

power each; and each engine had two horizontal cylinders, the

pistons of which were connected with cranks at right angles to

each other, which gave motion to the large grooved wheels, around

which the endless rope passed, and by which the rope was put in

motion. The engines were built in Pittsburgh, and could be started

and stopped very quickly. One engine only was used at a time,

but two were provided, for the greater security. Hemp ropes were

at first used, and gave much trouble, as they varied greatly in

length with changes in the weather, although sliding carriages

were prepared to keep them stretched without too much strain;

but wire ropes were afterwards substituted, and were a great improvement."

In the absence of inclined planes, horse power was sometimes

used on the heavy grades of early roads, even after locomotives

drew trains on level portions of such lines.

In the famous work of Charles Dickens, entitled American Notes,

he gives the following description of his

JOURNEY OVER THE PLANES OF THE ALLEGHENY PORTAGE

RAILROAD.

"We left Harrisburg on Friday. On Sunday morning we arrived

at the foot of the mountain which is crossed by railroad. There

are ten inclined planes, five ascending and five descending; the

carriages are dragged up the former, and let slowly down the latter,

by means of stationary engines; the comparatively level spaces

between being traversed, sometimes by horse, and sometimes by

engine power, as the case demands. Occasionally the rails are

laid upon the extreme verge of a giddy precipice; and looking

from the carriage window, the traveler gazes sheer down, without

a stone or scrap of fence between, into the mountain depths below.

The journey is very carefully made, however, only two carriages

traveling together; and while proper precautions are taken, is

not to be dreaded for its dangers."

PORTAGE RAILROADS AND THEIR USES.

The application of a number of the early railways to purposes

similar to those served by portages in the Indian and primitive

American systems of transportation, was probably better illustrated

by the Portage Railroad than any other line, and this fact presumably

suggested its name. Soon after its construction it was applied

to the novel purposes described in the following statement: "In

October, 1834, Jesse Chrisman, from the Lackawanna, a tributary

of the North branch of the Susquehanna, loaded his boat, named

'Hit or Miss,' with his wife, children, beds, furniture,

pigeons, and other live stock, and started for Illinois. At Hollidaysburg

(on the east side of a high ridge of the Allegheny), where he

expected to sell his boat, it was suggested by John Dougherty,

of the Reliance Transportation Line, that the whole concern could

be safely hoisted over the mountain and set afloat again in the

canal. Mr. Dougherty prepared a railroad car to bear the novel

burden. The boat was taken from its proper element and placed

on wheels, and under the superintendence of Major C. Williams

the boat and cargo at noon on the same day began the progress

over the rugged Allegheny. All this was done without disturbing

the family arrangements. They rested a night on the top of the

mountain, descended the next morning into the valley of the Mississippi,

and sailed for St. Louis. After this incident boats were so constructed

that they could be divided into sections and hauled over the railroad

on trucks without breaking bulk, but they were not extensively

used until about 1840. Cars were also used which could be lifted

from their trucks and loaded on boats of special construction."

METHOD OF OPERATION.

At a meeting, held in 1885, of Juniata boatmen, at Hollidaysburg,

Captain D. H. Boulton read a paper describing the travel on the

Portage Railroad, which contained the following statement:—

"The cars were loaded at Hollidaysburg, freight lifted from

the gunwale to the cars by main strength. As many of you remember,

if we worked hard all night, and started off in the morning, we

had the pleasant assurance that, if we were so fortunate as to

get over our thirty-six miles of road that day, we would have

the privilege of loading in the Johnstown freight house the next

night, sometimes working seventy-two hours consecutively in busy

seasons. This we called 'a bad run.' When loaded, they were hauled

by teams to Gaysport. The official in charge was not then called

conductor, but captain. We were all captains. He having received

from the collector's office his passport or right of way (the

cars were weighed by H. A. Boggs, or some other weigh master of

the honest old commonwealth), we were ready to start. A boat loaded

from ten to twelve cars. This made two trains of five or six cars

each, and was taken in charge by two men. The front car was the

lever car. The brakes were wooden blocks drawn down on top of

the wheels by means of it long pole at the side of the car. It

was a rare thing to have more than one lever car to a train. We

now attach to an engine, and are hauled to the foot of Plane No.

10 up a fifty-foot grade by Barney McConnell or Eli Yoder. Here

Galbraith, McCormick, or Gardner, with their strong teams, would

drag us, two or three cars at a time, to the hitching ground.

'Your clearance, captain,' would cry the familiar voice of Thomas

Holiday or James McKee. After satisfying them, that this was the

train entitled to pass, they would attach our cars to a hempen

rope by means of a hempen stop. (In after days wire rope and iron

chains took the place of these). Two cars being drawn up, the

process was repeated until the entire train bad arrived at the

top of the planes."

FIRST ASCENT OF AN INCLINED PLANE BY A LOCOMOTIVE.

In the reminiscences of Mr. W. Milner Roberts, one of the distinguished

early American railway engineers, which he read at a meeting of

the American Society of Civil Engineers, in May, 1878, he said:—

"In 1836, my friend William Norris, invited me to meet a

number of gentlemen to witness a promised performance of one of

his locomotives, namely, to take a passenger car (eight-wheeled),

with fifty persons in it, up the Schuylkill inclined plane, at

the rate of ten miles an hour. The first morning this experiment

was to be tried it was found that some malicious or humorous individual

had greased the track, which prevented the test for that time,

but shortly after, when the grease had been removed, his locomotive

actually performed as he had promised. A careful record of the

performance was printed in a quarto pamphlet at the time, but

I have not seen it for a great many years. One of the passengers

was an English officer, who (as Mr. Norris afterward told me),

when be related the occurrence in England, was not credited, the

railroad savants on the other side having already 'decided' that

the limit of locomotive possibilities stopped very far short of

422 feet per mile rise, which was the grade of the Schuylkill

plane. The length of this plane was about half a mile."

Other notable performances in hill-climbing of American locomotives,

constructed by various builders, occurred at later dates, and

after the fact became well established that locomotives could

ascend grades as heavy or even heavier than those on which inclined

planes bad been constructed, few or none of these devices were

applied to new roads intended for miscellaneous traffic, and those

in existence were supplemented. by tracks available for locomotives

as speedily as possible. This remark, however, does not apply

to some of the coal or other mining roads.

Transport Systems

| Antebellum RR | Contents

Page

|