RIVALRY BETWEEN LAND AND WATER ROUTES.

PAUCITY OF INTERSTATE-FREIGHT MOVEMENTS OVER ARTIFICIAL

CHANNELS IN 1840,

AND CAUSES WHICH CHECKED THEIR GROWTH.

THE condition of transportation development in the United States

in 1840 is peculiarly instructive in connection with the projects

then seriously discussed, and controversies that have agitated

the country since that time, relating to the comparative cost

on land and water routes of lengthy freight movements, and the

sort of discrimination which fixes the charges for them at a much

lower rate per ton per mile than the rate imposed on short freight

movements.

In 1840 the power to make such distinctions on a scale of considerable

national significance was vested chiefly in state governments.

The only two lines over which they could be made effectually were

the New York canals and the main line of the state of Pennsylvania,

both of which were under the management of political officials,

controlled, directly or indirectly, by legislatures; and every

other railroad or canal then existing that was of sufficient length

to engage extensively in through interstate-commerce movements

had been assisted by state loans or state stock subscriptions

to an extent that would justify absolute control of the general

subject of the relations between through and local rates.

It was, therefore, the right and duty of the people and their

direct agents to decide what those relations should be. If rates

were adjusted on erroneous principles they suffered as taxpayers,

because they were the chief financial supporters of all the railways

and canals then existing, either by direct outlays, such as those

made by New York and Pennsylvania for constructing their state

works, or by indirect outlays, such as those made in various other

states through subscriptions to stock, or loans of state bonds.

The practical decision generally reached on this question,

in 1840 and for some years later, both by the state governments

in imposing tolls, and most of the private companies in their

combined charges for the equivalent of tolls and freight, was

to impose a given rate per ton per mile, without regard to distance.

This system had a thorough trial. The idea which found enthusiastic

advocates at a later period, that no distinctions of the kind

indicated should be made, or more especially none in favor of

long movements, was extensively tested, and the results are known.

Indeed a number of the prevailing practices and prejudices were

in favor of discriminations in behalf of local trade and travel,

and if decisions of the United States courts had not severely

checked such tendencies it would be difficult to say how far they

might have been carried.

A principal effect of this restrictive or discriminating policy

was a failure of lengthy lines to serve a leading end of their

existence. In other words, there were no extensive through or

interstate-freight movements of bulky articles over artificial

land or water routes in 1840. The most important channels for

such movements were the New York canals, and official reports

of their operations in 1840 show that in that year, out of a total

movement of 1,417,046 tons, in both directions, the proportion

received from other states was 214,456 tons, a little more than

one-seventh of the entire movement, and the value of all such

receipts, via Buffalo and Oswego, was only $7,877,358. The Pennsylvania

main line had failed, most disastrously, to serve as a favorite

channel for east-bound through movements of bulky western products.

In 1835 the entire movement over the Portage Railroad was only

about fifty thousand tons, and although this may have been subsequently

increased, the eastbound through-freight movement over that road

never reached considerable magnitude. This was partly because

the composite character of the Pennsylvania main line, with its

changes from canals to railroads, rendered it unable to compete

in cost with the cheaper water channels of New York, and partly

because the lakes furnished better feeders of traffic than the

Ohio river; but there was a comparatively small amount of eastbound

through movements on both these lines combined, and the principal

advantage, in a national commercial point of view, resulting from

the construction of the main line of the Pennsylvania state works,

hinged on the fact that it enabled Philadelphia merchants to retain

western trade which they would have lost without such aid. On

account of the lower latitude in which the Pennsylvania canals

were located, they could be opened earlier in the spring, and

kept open later in the fall, than the New York canals, and they,

therefore, furnished available channels of trade to Philadelphia

and other portions of Pennsylvania during some weeks of every

season at periods when Now York did not possess similar advantages.

HOW THE GREAT WESTERN EMIGRATION MOVEMENT WAS MADE.

The following instructive and interesting account of the method

of conducting the emigration movement to the Mississippi valley

during the fourth decade is furnished in Flint's History of the

Mississippi Valley, published in 1832:—

"On account of the universality and cheapness of steamboat

and canal passage and transport, more than half the whole number

of immigrants now arrive in the west by water. This remark applies

to nine-tenths of those that come from Europe and the northern

states. They thus escape much of the expense, slowness, inconvenience,

and danger of the ancient, cumbrous, and tiresome journey in wagons.

They no longer experience the former vexations of incessant altercations

with landlords, mutual charges of dishonesty, discomfort from

new modes of speech and reckoning money, from breaking down carriages,

and wearing out horses. . . . Immigrants from Virginia, the two

Carolinas, and Georgia still immigrate, after the ancient fashion,

in the southern wagon. This is a vehicle almost unknown at the

north, strong, comfortable, commodious, containing not only a

movable kitchen, but provisions and beds. Drawn by four or six

horses, it subserves all the various intentions of house, shelter,

and transport, and is, in fact, the southern ship of the forests

and prairies. The horses that convey the wagon are large and powerful

animals, followed by servants, cattle, sheep, swine, dogs, the

whole forming a primitive caravan, not unworthy of ancient days,

and the plains of Mamre. The procession moves on with power in

its dust, putting to shame and uncomfortable feelings of comparison

the northern family with their slight wagon, jaded horses, and

subdued though jealous countenances. Their vehicle stops; and

they scan the staunch strong southern hulk, with its chimes of

bells, its fat black drivers, and its long train of concomitants,

until they have swept by.

Perhaps more than half the northern immigrants arrive at present

by way of the New York canal and lake Erie. If their destination

be the upper waters of the Wabash, they debark at Sandusky, and

continue their route without approaching the Ohio. The greater

number make their way from the lake to the Ohio, either by the

Erie and Ohio or the Dayton canal. From all points, except those

west of the Guyandot route and the national road, when they arrive

at the Ohio, or its navigable waters, the greater number of the

families 'take water.' Emigrants from Pennsylvania will henceforth

reach the Ohio on the great Pennsylvania canal, and will 'take

water' at Pittsburgh. If bound to Indiana, Illinois, or Missouri,

they build or purchase a family boat. Many of these boats are

comfortably fitted up, and are neither inconvenient nor unpleasant

floating houses. Two or three families sometimes fit up a large

boat in partnership, purchase an 'Ohio Pilot,' a book that professes

to instruct them on the mysteries of navigating the Ohio; and

if the Ohio be moderately high, and the weather pleasant, this

voyage, unattended with either difficulty or danger, is ordinarily

a trip of pleasure. A number of the wealthier emigrant families

take passage in a steamboat."

FREIGHT TARIFFS PROPOSED BY ROBERT FULTON IN 1796.

Recurring to the main topic, of the deplorable lack of extensive

through interstate-freight movements over all artificial channels,

which was largely due to the fact that no material distinctions

were made in toll or freight charges to favor or encourage lengthy

movements, it is a notable circumstance that forty-four years

before the period under discussion, long before a single mile

of railway had been constructed, and when canal improvements were

only beginning to attract serious consideration, Robert Fulton,

the pioneer of successful steamboat operations, had clearly pointed

out the necessity of such distinctions or discriminations.

In a letter be addressed to Thomas Mifflin, Governor of Pennsylvania,

in 1796, advocating the construction of a canal between Pittsburgh

and Philadelphia, he very forcibly depicted the necessity of lowering

the charges per ton per mile on distant movements, and practically

constructed for this projected line a freight tariff analogous

to those in force during late years on many railway lines, but

which few or none of the railway or canal lines existing in 1840

had the wisdom to adopt. In this remarkable letter Mr. Fulton,

in describing the system that should be adopted in connection

with the management of a canal extending from Philadelphia to

Pittsburgh, said:—

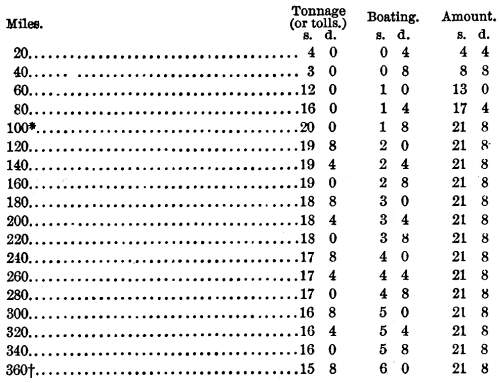

"If I proceed with this progressive and creative system till

a canal reached Fort Pitt, which, with some bends, I will call

360 miles, the country which the canal would accommodate would

widen as it was more remote from Philadelphia. For instance, the

man who lived 20 miles from Philadelphia might convey his goods

7 to the canal; the man at 40 miles distance might go 14 or 15

to the canal; at 60 miles, 20 to the canal, and so on, till at

the extremity of 360 miles they would probably go 50 on each side

to the canal; hence, if I average the whole, such a canal may

be said to accommodate a country 360 miles long and 50 miles wide,

on which the tonnage (or tolls) must now be regulated.

The man who resides 20 miles from Philadelphia, and 7 from

the canal, should he convey a ton of goods by land, it would be

worth at least fifteen shillings, as it would employ a man and

two horses two days.

Thus the saving would be six shillings, and the tonnage (tolls)

should increase to a certain sum on the first hundred miles of

canal, keeping much within the limits of land carriage, then decrease

as the boating increased, in order to draw the trade of the

back country into the canal.

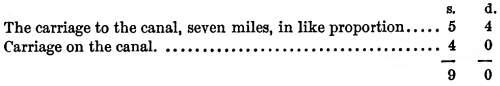

The expense of boating a ton 20 miles will be as follows:—A

man, boy, and horse will convey forty tons 20 miles for ten shillings,

which is three pence per ton for 20 miles; but to allow for contingencies,

say four pence per ton for boating 20 miles, the tonnage and boating

on the 360 miles should then be regulated, perhaps, in the following

order:—

* This being within the limits of land carriage,

the tonnage (tons) must now begin to decrease as the boating is

increased.

† If the boats return without back

carriage, the expense of boating, which on the 360 miles is six

shillings, must be deducted from the tolls, and in proportion

on the various parts of the canal.

By this system the country, at the extremity of 360 miles,

would deliver goods at Philadelphia for twenty-one shillings

and eight pence, which is the same as paid at the distance

of one hundred miles, to which the land carriage to the

canal must be added. But as such a system would open a market

to the remote country, every acre of ground within reach of the

canal would be more valuable, and the carriage to the canal must

be borne for some years. But as population increased, and the

tonnage on the main line became productive, lateral branches would

be cut from the canal, and thus further improve the country, the

tonnage (or tolls) on such branches being proportioned, as before

stated, according to the distance from the city."

ELLET'S LAWS OF TRADE, SHOWING INJURIOUS EFFECTS

OF

OVERCHARGES AND UNDERCHARGES

Other significant references to this subject were contained

in a pamphlet devoted to it, entitled Laws of Trade, and a popular

explanation of its contents, published by Charles Ellet, jr.,

in 1840. He was one of the most distinguished civil engineers

of that era. The detailed explanations are so abstruse that it

is almost impossible for unprofessional readers to fully comprehend

them, or to recognize the force of the statements and arguments

presented. One of the leading ideas advanced was that the tax-payers

of the states which had made large investments in public works

were then suffering pecuniarily, through avoidable diminutions

of the revenue of those lines, and that the country at large was

not benefited to the extent that was desirable and, possible,

on account of a failure to construct toll sheets in accordance

with principles which, in some of their most vital features, substantially

accord with those enunciated by Fulton in 1796. Mr. Ellet, in

defining the most judicious charge on articles of heavy burden

and small value, contended that the charge at each point should

be "proportional to the ability of the article to sustain."

This is only a paraphrase of the expression "what the traffic

will bear," and Mr. Ellet approached still nearer to that

famous expression by speaking of "the greatest tax for carriage

which the commodity will bear." His pamphlet probably had

considerable influence in directing the attention of railway managers

to the importance of remodeling their tariffs in a way that would

encourage and greatly increase lengthy through movements of cheap

and bulky freight. He was, perhaps, the first person in the United

States to lay down precise rules for the framing of toll sheets

and freight charges on internal improvements, and some of his

views might be advantageously adopted by those who have since

carried the principle of cheapening lengthy movements to excessive

and injurious limits.

To promote ease of explanation he adopted a distinction between

freight and toll, which makes his remarks applicable to railway

lines owned and operated by a given company, as well to state

canals or railways, on which boats or cars were furnished by individuals.

He said: "I shall designate by freight every expense

actually incurred in the carriage of the community, and by toll

the clear profit on its transportation; so that if the carrier,

or transporting company, charge seven mills per mile for the carriage

of one ton of any article, and the cost of repairs and superintendence

of the line due to the passage of that ton is three mills per

mile, I call the freight on the article one cent per ton

per mile, and any charge, exceeding this three mills, which is

assessed by the state or company, is what I denominate their toll."

He contended that this toll was improperly and unjustly levied

on all American lines in 1840, and gave a number of illustrations

of the losses of trade arising from the system of uniform charges

per mile. The list of conclusions he reached embraced the following:—

"At the distance of one hundred miles from the mart, in

the usual tariffs, a commodity is charged one dollar where it

might bear a charge of three, and at three hundred miles it is

charged three dollars where it could bear but one."

"The greater the distance the commodity is carried the

less should be the toll levied upon it."

"However we depart from the charge which will yield the

greatest revenue, there will be an increase or diminution of tonnage,

and, of course, always a decrease of revenue. If the departure

be an overcharge, the tonnage will be reduced a quantity directly

proportional to the value of the overcharge, and the revenue proportional

to the square of that departure."

"Where the object is to obtain the greatest possible revenue,

it is a general law, susceptible of satisfactory proof, that the

charge for toll should not exceed half that charge which would

exclude the trade from the line."

"Where the most judicious charge is levied, the tonnage

of the line will be one-half of the tonnage which would be obtained

if no toll at all were exacted."

"Whatever unnecessary tax is levied on the trade is at

least so much deducted from the revenue of the improvement."

In discussing the methods that should be pursued to derive

the greatest profit from a given trade in articles of heavy burden

and small value, he laid down the following rule:—

"To attain the greatest possible revenue from the trade,

under a uniform charge, the profit received from each ton must

be equal to the expense of its carriage."

This rule has been disregarded or violated in many modern railway

operations, in the direction of undercharges, as persistently

as the rules relating to overcharges were violated by managers

of the early lines. An immense amount of freight has been carried

on railways at rates that yielded no profit whatever over absolute

cost of movement. Many causes contributed to such practices, some

of the most prominent of which are active rivalries and aggressive

railway wars. If Mr. Ellet's rule is even approximately correct,

it may suggest advantageous changes in some freight tariffs wherever

the desire to secure the greatest possible revenue, which is always

strong, is not counteracted by antagonistic requirements.

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN RAIL AND WATER CARRIERS.

The systems pertaining to freight charges briefly discussed

above, and plans for reducing the cost of railway freight movements,

have an important bearing on the railway systems fairly commenced

and projected in 1840. There were few problems then more earnestly

discussed in engineering, commercial, and speculative circles,

than the extent to which railways would probably be able to compete

with canals and rivers as freight carriers. The groundwork of

extensive practical tests of this question had already been established,

by the rapidly advancing chain of railway connections running

parallel with the Erie Canal; the commencement of the construction

of the New York and Erie Railroad; the earnest advocacy of the

completion of lines which would furnish railway connections between

the city of New York and Albany, and thus parallel the North river;

the near approach of the Reading railroad to the Schuylkill anthracite

regions for the purpose of competing with the Schuylkill Canal

as a coal carrier; the completion of the Philadelphia, Wilmington

and Baltimore which furnished a railway link between Philadelphia

and Baltimore and thus presented a choice of routes to shippers

who had previously depended exclusively on the natural and artificial

water routes connecting the two cities; the completion of a new

railway and a now canal by the New Jersey companies connecting

Philadelphia and New York; and various other enterprises.

Aside from these works, on which the merits and demerits of

each of the respective land-and water-route methods have been

tested in thousands of competitive struggles, extending through

many years, and characterized by every variety of incident that

the ingenuity, inventive genius, and adventurous spirit of a progressive

people could suggest, a large proportion of all the railways projected

in 1840 and built for some years after that period were vitally

affected by the varying aspects of the irrepressible conflict

between land and water routes as freight carriers.

The topography of the country created an immense basis of such

struggles, in the oceanic boundary of the Atlantic seaboard on

the east, the gulf of Mexico on the south, the lakes, St. Lawrence,

and New York canals on the north, the Mississippi and its tributaries

on the west, and the Appalachian chain which separated the seaboard

states from those lying west of its mountain barriers.

Under old systems there were only two great natural outlets—the

Mississippi and the St. Lawrence—for the bulk of the products

of the interior portions of the United States lying west of the

Appalachian chain. All modern American improvements, whether railways

or canals, intended to affect the trade of this vast and productive

region, have aimed at diverting portions of it to the districts

or states which contained the principal part of such improvements.

The entire trade of the country of national significance had

tended towards one of the four water systems which in 1840 were

the practical boundaries of American development. The trade all

went to and from either the Atlantic coast on the east, the gulf

on the south, the lakes and the St. Lawrence on the north, or

the Mississippi and its tributaries on the west. Therefore, every

railway intended to serve anything more than local purposes aimed

at a connection with one of these water channels, and the projectors

of nearly all lines or combinations of lines which were expected

to become parts of a through route of considerable consequence

endeavored to establish a link between two or more of the four

great water systems.

After such connections were formed, it still remained a question

whether extensive links would prove profitable, and a leading

factor in this problem was the relative cost of the through-rail

movements contemplated and the rival movements that could be made

over water routes, or combinations of rail and water routes. There

has probably never been in the trade history of the world a contest

so complicated as that which has arisen from the protracted struggle

between these rival systems. It has not merely been a fight between

an elephant and a whale, or between land routes ranged on one

side and water routes on the other, but between the two rival

routes of the lakes and the Mississippi, or the two whales; between

various land routes leading eastward, which might be compared

to gigantic elephants, and between combinations of elephants with

little whales on one side and combinations of big whales and little

elephants on the other. Two of the general tendencies that have

prevailed amid many mutations are a steady cheapening of the cost

of freight movements and an increase of the relative magnitude

of the movement made eastward, parallel with the natural water

route of the lakes and the St. Lawrence, as compared with the

movement made southward, via the Mississippi.

If methods had not been devised for cheapening rail movements

to a marvelous extent, their share in this great struggle would

have been comparatively insignificant, but the fact that they

were thus cheapened forms one of the most momentous changes in

modern industrial history, and one of the cheapening agencies

to which attention was first directed was the application of the

Fulton and Ellet principles to extensive through-rail movements.

Others were furnished by a long line of engineering and mechanical

improvements.

Transport Systems

| Antebellum RR | Contents

Page

|