|

THE AMERICAN RAILROAD,

Harper's Monthly—ca. 1875

I PROPOSE to give, as far as

it can be given within the limits of a single magazine article,

some account of the origin, history, and internal organization

of the American railroad. Into the question so abundantly discussed

of late in the public prints and periodicals, and now even in

political caucuses and conventions, concerning the mutual rights

and obligations of the railroad companies and the public, I shall

not enter. Yet it may contribute something to a better understanding,

and so indirectly to a solution of that problem, to have a clear

idea of what a railroad corporation is, what are the hazards,

what the toils, what the duties, difficulties, and dangers, of

those who are connected with, and who have done most to create,

develop, and carry on, these great highways of the present century,

the arteries which supply the whole body politic with its vital

circulation—trade and commerce. I PROPOSE to give, as far as

it can be given within the limits of a single magazine article,

some account of the origin, history, and internal organization

of the American railroad. Into the question so abundantly discussed

of late in the public prints and periodicals, and now even in

political caucuses and conventions, concerning the mutual rights

and obligations of the railroad companies and the public, I shall

not enter. Yet it may contribute something to a better understanding,

and so indirectly to a solution of that problem, to have a clear

idea of what a railroad corporation is, what are the hazards,

what the toils, what the duties, difficulties, and dangers, of

those who are connected with, and who have done most to create,

develop, and carry on, these great highways of the present century,

the arteries which supply the whole body politic with its vital

circulation—trade and commerce.

The traveler going West steps to the ticket office of the Pennsylvania,

the Erie, or the New York Central Railroad. He purchases his ticket

for San Francisco. He gives his trunk to a baggage-master, gets

for it a little piece of metal, and sees and cares for it no more.

A porter shows him his place in the Pullman car. He takes his

seat, pulls off his boots, puts on his slippers, opens his bag,

takes out his Harper's Magazine, and his traveling cares

are at an end. For six days and nights he is rolled swiftly across

the continent. Engineers and conductors change. He is passed along

from one railroad corporation to another. At night his seat becomes

a bed, and he sleeps as quietly, or nearly so, as if in his own

bed at home. He traverses broad plains, passes over immense viaducts,

whirls swiftly over mountain torrents on iron bridges, climbs

or pierces mountains; but he never leaves his parlor; if need

be, his meals are brought to him where be sits; and at length,

after a week of luxurious though weary traveling, in which he

has been in the keeping of half a dozen different companies, and

has traversed over three thousand miles of country, part of it

uninhabited and desolate, he is set clown in the station at San

Francisco. He looks at the clock in the station-room, compares

it with the time-table in his hand, and finds that his journey

has been accomplished with all the regularity and punctuality

of the sun. His little piece of brass is given to an express agent

or a hackman, and when he reaches his hotel, the trunk which he

surrendered in Now York is in the great hall awaiting him. It

seems a very simple business; and if perchance through all this

journey he finds the dinner at one waiting-place cold, or the

conductor on one part of his trip discourteous, or the train stopped

at any point in the long ride beyond his expectations, or his

arrival at his destination delayed beyond the appointed hour,

he is very apt to grumble inwardly if not vocally. How much money

has been put into this long line of rail; how much has been sunk

in unsuccessful experiments; how many rich men have been ruined

before the work was done; how many sleepless nights surveyors

and contractors have spent in providing this marvelous highway;

how intricate and involved is the system of co-partnership that

is necessary to such a continuous transportation "without

change of cars;" what a gigantic undertaking it is to administer

this system, with its thousands of employees; how wide awake the

engineers have been that the traveler may sleep; what dangers

they have had to face that he may ride in safety —of all

this he is unconscious, if not absolutely ignorant.

The Erie Railway, one of the longest lines of railroad in the

world, employs fifteen thousand persons in various occupations.

It is estimated that there is scarcely an hour of the day or night

when there are not one hundred trains in actual running along

its line. The administration of such a force of men, the management

of such a system of railroad trains, without clashing or collision,

requires executive ability of the very highest order. If, Sir,

you think it easy, count up the difficulties you have with your

own Irish gardener in the administration of your country place,

with its horse and cow; then multiply those difficulties by fifteen

thousand, and you have the problem of an American railroad president.

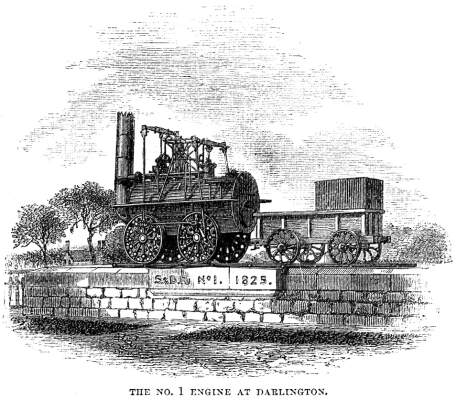

The railroad system has not yet

reached its semi-centennial. The 27th of September, 1825, may

be regarded as its birthday, if it can be said to have had a day

of birth. The railroad from Stockton to Darlington, in England,

had been completed. On the urgent recommendations of George Stephenson

the original plan of a wooden tramway had been abandoned, and

an iron railway had been substituted. Yielding to his persistency,

the directors of this newfangled and much ridiculed enterprise

permitted him to put upon the road, which they had intended only

for horse draught, a steam locomotive. A great concourse of people

assembled on the occasion of its opening, to glorify the success

or ridicule the failure of the man whom the multitude were equally

ready to canonize as the wisest or to condemn as the craziest

man in all England. Thoroughness was above all qualities a characteristic

of this father of railroads; hence, fortunately for his reputation,

and yet more fortunately for his work, he needed only an opportunity

to demonstrate the practicability of his plans. On the trial day

he was always ready; no overlooked or neglected point ever brought

him or his work into disrepute. A long procession of vehicles

was formed-six wagons loaded with coals and flour, a covered coach

containing directors and passengers, twenty-one coal wagons fitted

up for and crowded with passengers, and six more wagons loaded

with coals. Locomotive engine No. 1, driven by George Stephenson,

headed the procession. A man on horseback rode before, and heralded

the coming of the train. A great concourse of people, on horseback

and on foot, accompanied it; but not long. The horseman who heralded

was compelled to leave the track; the accompanying horsemen and

the runners were distanced; and the first train that ever carried

passengers finished its journey at the rate of from twelve to

fifteen miles an hour. The railroad system has not yet

reached its semi-centennial. The 27th of September, 1825, may

be regarded as its birthday, if it can be said to have had a day

of birth. The railroad from Stockton to Darlington, in England,

had been completed. On the urgent recommendations of George Stephenson

the original plan of a wooden tramway had been abandoned, and

an iron railway had been substituted. Yielding to his persistency,

the directors of this newfangled and much ridiculed enterprise

permitted him to put upon the road, which they had intended only

for horse draught, a steam locomotive. A great concourse of people

assembled on the occasion of its opening, to glorify the success

or ridicule the failure of the man whom the multitude were equally

ready to canonize as the wisest or to condemn as the craziest

man in all England. Thoroughness was above all qualities a characteristic

of this father of railroads; hence, fortunately for his reputation,

and yet more fortunately for his work, he needed only an opportunity

to demonstrate the practicability of his plans. On the trial day

he was always ready; no overlooked or neglected point ever brought

him or his work into disrepute. A long procession of vehicles

was formed-six wagons loaded with coals and flour, a covered coach

containing directors and passengers, twenty-one coal wagons fitted

up for and crowded with passengers, and six more wagons loaded

with coals. Locomotive engine No. 1, driven by George Stephenson,

headed the procession. A man on horseback rode before, and heralded

the coming of the train. A great concourse of people, on horseback

and on foot, accompanied it; but not long. The horseman who heralded

was compelled to leave the track; the accompanying horsemen and

the runners were distanced; and the first train that ever carried

passengers finished its journey at the rate of from twelve to

fifteen miles an hour.

It is not easy for us, with the whistle of the locomotive as

familiar in our ears as the sound of the church bell, to conceive

the difficulties under which the early promoters of railroads

labored. The necessity of making a comparatively level roadway

was apparent from the first. How this was to be accomplished was

not so evident. That the returns in traffic would ever compensate

for the prodigious expense involved was believed by few. That

steam could ever be practically employed for draught in such a

way as to compete in speed and utility with horses was ridiculed

by almost every one. This ridicule was not confined to unintelligent

and ignorant minds. The ablest engineers combined with the common

people in declaring it impossible. They demonstrated its impossibility.

Scientific men declared that it could not be done. Practical men

declared that the dangers would render it inconceivably hazardous

to public safety, even if the dream of the visionary enthusiasts

could be realized. Political economists cried out against an imaginary

reform, the result of which would be to throw out of employment

drivers of stage-coaches and teamsters and innkeepers, and the

whole class of artisans and traders whom the then common methods

of traffic kept busy. One of the ablest of English quarterlies,

one of the warmest friends of the movement, thus ridiculed the

absurd expectations of some of its sanguine promoters:

"What can be more palpably

absurd and ridiculous than the prospect held out of locomotives

traveling twice as fast as stage-coaches? We should as soon expect

the people of Woolwich to suffer themselves to be fired off upon

one of Congreve's ricochet rockets as trust themselves to the

mercy of such a machine going at such a rate." A Parliamentary

opponent to the first great passenger line, the Manchester and

Liverpool, declared that it would be impossible to work the engine

against a gale of wind. Another prophesied that it would deteriorate

land in the vicinity of Manchester alone to the extent of £20,000.

When Parliamentary opposition was at length silenced by argument

or hushed by money—the charter of the road cost, in immaculate

England, forty years before the days of Credit Mobilier, £27,000—opposition

and obstacle had but begun. The surveyors were mobbed by the people;

the work was impeded when commenced; engineers had to learn their

art by experience, and of course by one that was prolonged and

costly. No less resolute and determined a will, no less practical

and sagacious an engineer, than George Stephenson could have carried

to its consummation the first great trunk line. It was hard for

him, but it was fortunate for the world, that this road presented

so many of the difficulties with which in all districts railroad

engineering has to cope. On the thirty miles between Liverpool

and Manchester there were under or over the railroad sixty-three

bridges. The stone cutting at Olive Mount is to-day one of the

most formidable in the world: it is two miles long, and in some

places one hundred feet deep. The roadway across Chat Moss is

one of the wonders of railway enterprise. Considering the circumstances

under which it was devised and executed, it deserves to rank with

the chiefest engineering exploits of the century. "What can be more palpably

absurd and ridiculous than the prospect held out of locomotives

traveling twice as fast as stage-coaches? We should as soon expect

the people of Woolwich to suffer themselves to be fired off upon

one of Congreve's ricochet rockets as trust themselves to the

mercy of such a machine going at such a rate." A Parliamentary

opponent to the first great passenger line, the Manchester and

Liverpool, declared that it would be impossible to work the engine

against a gale of wind. Another prophesied that it would deteriorate

land in the vicinity of Manchester alone to the extent of £20,000.

When Parliamentary opposition was at length silenced by argument

or hushed by money—the charter of the road cost, in immaculate

England, forty years before the days of Credit Mobilier, £27,000—opposition

and obstacle had but begun. The surveyors were mobbed by the people;

the work was impeded when commenced; engineers had to learn their

art by experience, and of course by one that was prolonged and

costly. No less resolute and determined a will, no less practical

and sagacious an engineer, than George Stephenson could have carried

to its consummation the first great trunk line. It was hard for

him, but it was fortunate for the world, that this road presented

so many of the difficulties with which in all districts railroad

engineering has to cope. On the thirty miles between Liverpool

and Manchester there were under or over the railroad sixty-three

bridges. The stone cutting at Olive Mount is to-day one of the

most formidable in the world: it is two miles long, and in some

places one hundred feet deep. The roadway across Chat Moss is

one of the wonders of railway enterprise. Considering the circumstances

under which it was devised and executed, it deserves to rank with

the chiefest engineering exploits of the century.

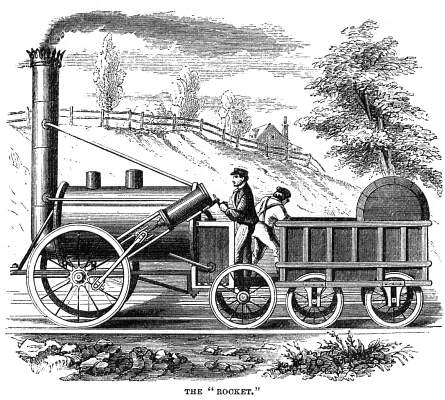

But if the railroad in its inception met with great impediments

from its foes, their opposition is not to be wondered at. For

the schemes of the first railroad men were often visionary and

impracticable. Those that stood the test of time remain; the others

are forgotten. That the world did not at first discriminate between

them is not surprising. The curiously wild attempt to construct

the Erie Railway on piles, and so save the expense of embankments,

is but one of the numerous costly experiments which rendered no

other service to any one than the experience they brought. How

singularly crude were the ideas of the railroad pioneers receives

a still more curious illustration in the history of the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad, one of the earliest constructed on American

soil. The first locomotive was made with sails, to be propelled

by the wind, like a ship. At the famous trial of locomotives at

Liverpool in 1829 four engines put in an appearance. Of the four

George Stephenson's Rocket was the only one that achieved any

thing. Of the others two broke utterly down; the third could attain

at its utmost but a speed of five or six miles an hour. In number

the failures preponderated; it is not strange that for a time

they preponderated in the influence which they exerted on the

public mind.

It will render our task of tracing

the history and describing the organization of the American railroad

simpler if we take a single one as illustrative of the entire

system. For that purpose I have chosen the Erie Railway. It is

one of the longest, as it is one of the oldest, on the continent.

In its early history it met and conquered obstacles which might

well have sufficed to crush an enterprise financially much stronger.

A large part, of its course lay through an absolutely trackless

wilderness. To reach its destination it was necessary to climb

a mountain range over 1700 feet above the level of the sea, and

mate its way along the course of a stream which flows between

almost precipitous walls of rock. As a monument of engineering

skill it is without a superior to-day in America—certainly

if the times and circumstances in which it was constructed be

taken into account. It will render our task of tracing

the history and describing the organization of the American railroad

simpler if we take a single one as illustrative of the entire

system. For that purpose I have chosen the Erie Railway. It is

one of the longest, as it is one of the oldest, on the continent.

In its early history it met and conquered obstacles which might

well have sufficed to crush an enterprise financially much stronger.

A large part, of its course lay through an absolutely trackless

wilderness. To reach its destination it was necessary to climb

a mountain range over 1700 feet above the level of the sea, and

mate its way along the course of a stream which flows between

almost precipitous walls of rock. As a monument of engineering

skill it is without a superior to-day in America—certainly

if the times and circumstances in which it was constructed be

taken into account.

The first step in the construction of a railroad is its conception.

The originator of a successful railroad must be something of a

prophet. He must not only be wise to see, but sagacious to foresee.

For railroads do not merely supply a demand which already exists;

they create it. The railroad originator always appears to be an

enthusiast to his fellows. The first successful English railroad

ran from Stockton to Darlington. The latter town lies in the heart

of one of the richest mineral fields in the north of England.

The former is situated near the mouth of the Tees, and is the

nearest sea-port town. How little even the founders conceived

the business which this line would build up is indicated by the.

fact that they counted on a coal traffic of 165,000 tons, and

that in 1860 that traffic had actually grown to over 3,000,000

tons annually! They consented without protest to a clause in their

charter limiting their freight charges on coal for exportation

to a half-penny per mile, for that branch of their trade they

regarded as entirely subsidiary. Yet in the course of a very few

years it constituted the main bulk of their business. In ten years

this railroad had converted a solitary farmhouse in the midst

of unproductive pasture land into a town of six thousand inhabitants,

which has since more than quadrupled in size. Of course we could

cite abundant illustrations more striking from the history of

American railroads. We cite this because it was prophetic of all

the subsequent history of railroad enterprise.

The conception of a railroad

is often a flash of intuition in the individual mind. But before

the originator can realize his vision he must succeed in inspiring

other minds with his own conviction and enthusiasm, and this is

always a work of time. Of the prenatal history of the railroad

the Erie is an illustrious example. The conception of a railroad

is often a flash of intuition in the individual mind. But before

the originator can realize his vision he must succeed in inspiring

other minds with his own conviction and enthusiasm, and this is

always a work of time. Of the prenatal history of the railroad

the Erie is an illustrious example.

In 1779 General James Clinton and General Sullivan, at the

close of an expedition against the Iroquois Indians in the southern

tier of counties of New York State, proposed to Congress the construction

of what they termed an Appian Way from the city of New York to

Lake Erie. The great inland seas which we call lakes, and which

have done so much to develop the rich but formerly inaccessible

West, were at that time separated from the sea-coast by the mountain

range which stretches, with here and there a break, from the Gulf

States to the river St. Lawrence. The great West, the future but

then unrecognized granary of the nation, was more remote from

the Atlantic than is to-day the empire of Japan. To the Clintons

New York owes the two great highways which have rendered her chief

city the metropolis of the nation—the Erie Canal and the

Erie Railway. The Appian Way never got further in construction

than an ineffectual application to Congress for an appropriation.

But the dream of the father descended to the son, and De Witt

Clinton, who pushed forward the act authorizing the construction

of the Erie Canal secured for it the support of the southern counties

by promising in return his influence, and that of his party, for

the construction of another highway through the region and along

the line designated by his father. Fifty years passed away before

the first step was taken toward the realization of this Appian

Way. Meanwhile the methods of intercommunication had changed.

The canal had supplanted the public road, and the railway was

beginning to supplant the canal. And at last, in April, 1832,

three years after George Stephenson ran his first passenger locomotive

over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the Legislature of

New York granted a charter for the construction of a road of iron

where General James Clinton had dreamed, only of one modeled as

well as named after the famous highway of ancient Rome. This charter

affords a curious illustration of the shortsightedness that is

characteristic of the cunning of politicians. It forbade all connections

with Pennsylvania and New Jersey railroads. For is it not the

office of a Legislature to promote only the interests of its own

State? So the one terminus was made at Piermont, the nearest accessible

point in the State, on the Hudson River, to the city of New York;

the other was made at Dunkirk, the most remote western harbor

on Lake Erie. But through cars have long since been run direct

both to Cincinnati and Chicago; and the long pier which was built

out over the flats of the Tappan Zee, at Piermont, to make the

steamboat connections with the city is only useful as a permanent

warning to legislators that it is their business to facilitate

the natural course of trade, not to obstruct, to divert, or to

control it.

The railroad being conceived,

and the conception having gained sufficient adherents to furnish

a minimum of capital necessary to prove the dream of the originator

to be not all a dream, the next step is a survey. The railroad being conceived,

and the conception having gained sufficient adherents to furnish

a minimum of capital necessary to prove the dream of the originator

to be not all a dream, the next step is a survey.

If the reader will turn to any map of New York State, he will

find that the southern tier of counties, from the Hudson River

as far west as Binghamton, are intersected by mountain ranges,

whose abrupt and rugged character and wild and desolate features

can be but very inadequately indicated. He will see also traced

upon the map by insignificant-looking serpentine lines the course

of two great rivers, the Delaware and the Susquehanna, whose branches

are but sixteen miles apart at Deposit, while the waters of the

one empty into Delaware Bay, and those of the other into Chesapeake

Bay. These mountain lines indicate the difficulties to be overcome;

these river lines indicate the methods by which the railroad engineer

overcomes them.

The first work of the surveyor is to trice the general outlines

of his course. These are almost uniformly indicated to him by

the watercourses, for the water-courses indicate, first, natural

openings between the hills; second, an easy grade in ascending

from the lower to the higher levels. The Erie Railway enters the

hill country at Suffern's. It follows the Ramapo River for a score

or so of miles, strikes the Delaware at Port Jervis, follows the

tortuous course of that magnificent mountain torrent to Deposit,

crosses the mountains at that point, reaches the tipper waters

of the Susquehanna at the town of that name, leaves that river

to follow the Tioga, a branch of the same stream, parts from that

to avail itself of the valley of the Canisteo, crosses a short

piece of intervening country to reach and follow down the Genesee,

passes from that to the Alleghany, and does not finally abandon

the river valleys until it is within forty-five miles of its original

western terminus, Dunkirk. In its journey of 459 miles it has

availed itself of the valleys of seven rivers. In a somewhat similar

manner the Pennsylvania Central Railroad crosses the same great

mountain range by aid of the Susquehanna, the Juniata, and the

Conemaugh rivers; and the Pacific Railroad follows the Platte

River almost to its source in the Rocky Mountains on the eastern

side, and descends upon the western slope by the valleys of a

succession of less important but equally useful mountain streams.

The first duty of the railroad

surveyor, then, is to trace in a general way the course of the

projected railroad upon an ordinary map by means of a careful

study of its mountain ranges and its water-courses. The more detailed

and elaborate the map, the more perfect can he make his preliminary

and office survey. This being done, the real work of the survey

begins. For this purpose the chief engineer makes a general reconnaissance

of the whole ground, generally on horseback. He provides himself

with the best map or maps he can obtain. He picks up as best he

can more definite and precise local information. To succeed in

his work he must have qualities which are rare, qualities which

no mere school of engineering can impart. In his profession, as

in every other, there is a certain something indefinable in native

genius, something which may perish unused for want of development

and training, but which no mere development and training can wholly

supply. The engineer must be a man of ready parts. He must have

himself always well in hand. He must understand human nature,

and know how to deal with it. He must be equally at home in the

log-hut among the mountains and in the velvet-carpeted and mahogany

furnished office in the great city. He must be a man of quick

eye and abundant resources, able to meet an exigency, or to vary

in detail and on the moment a carefully matured plan for the purpose

of avoiding an unexpected obstacle, and reaching the general result

with the least expenditure of time and money. The engineer has

tunneled the Alps, and an expert assures us that with money enough

it would be possible to construct a permanent floating bridge

across the Atlantic. But there are a great many things which it

does not pay to accomplish, and the successful engineer must be

able to subordinate professional pride to practical results; to

avoid obstacles that can be avoided, and to overcome only those

that he can not escape; to make the fewest possible rock cuttings,

tunnels, culverts, and bridges; and to be known and honored less

for what he has done than for what he has avoided doing. The first duty of the railroad

surveyor, then, is to trace in a general way the course of the

projected railroad upon an ordinary map by means of a careful

study of its mountain ranges and its water-courses. The more detailed

and elaborate the map, the more perfect can he make his preliminary

and office survey. This being done, the real work of the survey

begins. For this purpose the chief engineer makes a general reconnaissance

of the whole ground, generally on horseback. He provides himself

with the best map or maps he can obtain. He picks up as best he

can more definite and precise local information. To succeed in

his work he must have qualities which are rare, qualities which

no mere school of engineering can impart. In his profession, as

in every other, there is a certain something indefinable in native

genius, something which may perish unused for want of development

and training, but which no mere development and training can wholly

supply. The engineer must be a man of ready parts. He must have

himself always well in hand. He must understand human nature,

and know how to deal with it. He must be equally at home in the

log-hut among the mountains and in the velvet-carpeted and mahogany

furnished office in the great city. He must be a man of quick

eye and abundant resources, able to meet an exigency, or to vary

in detail and on the moment a carefully matured plan for the purpose

of avoiding an unexpected obstacle, and reaching the general result

with the least expenditure of time and money. The engineer has

tunneled the Alps, and an expert assures us that with money enough

it would be possible to construct a permanent floating bridge

across the Atlantic. But there are a great many things which it

does not pay to accomplish, and the successful engineer must be

able to subordinate professional pride to practical results; to

avoid obstacles that can be avoided, and to overcome only those

that he can not escape; to make the fewest possible rock cuttings,

tunnels, culverts, and bridges; and to be known and honored less

for what he has done than for what he has avoided doing.

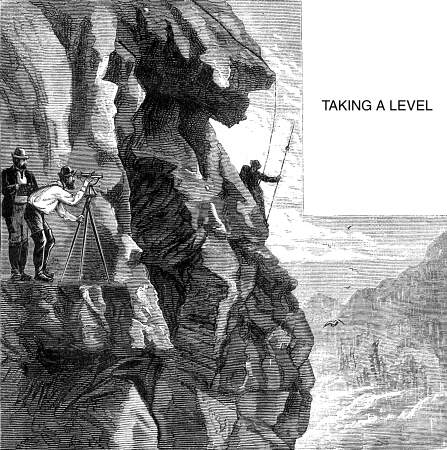

The more accurate survey now follows. This is always effected

in sections. It is performed by an engineer corps, which consists

of an assistant engineer, a transit-man, a leveler, a rod-man,

two chain-men, one or two flag-men, and a gang of axe-men. Where

the company are obliged to camp out, the necessary accessories

of a camp are added. The work of such a surveying party is always,

under the best circumstances, one of hardship and adventure. They

must stop at no obstacle; and the country presents innumerable

difficulties which the map had not reported, and even the reconnaissance

had not discovered. Morasses are to be traversed, streams are

to be crossed, precipitous hills to be climbed, impenetrable thickets

to be penetrated. The Erie Railway runs for miles along the banks

of the Delaware River, in many places upon a shelf cut in the

solid rock, fifty feet or more above the torrent. Yet somehow

along this seemingly inaccessible gorge the surveying party had

to make their way before the first blast could be fired to prepare

for the present rocky road-bed. It is said that at some points

they were lowered by ropes from the top of the cliff, and so,

hanging between heaven and earth, took their levels. The earliest

surveys of such works as the Pacific Railroad, through a country

absolutely a wilderness, and almost absolutely an untrodden wilderness,

are marvels of human capability.

The process of surveying does

not differ widely from that with which we may assume our readers

to be familiar in the laying out of town and farm boundaries and

of public highways, except in one important particular. In the

railroad survey the exact differences in level must be preserved

and respected. Every inequality must be noted. This is done by

the leveler, and is preserved by the profile map. Of these profile

maps there are two—one, the larger map, indicates the general

features of the route; the second and more detailed profile, or

series of profiles, preserves to the foot a careful record of

every inequality of ground over which the projected route is to

pass. These reports indicate exactly the obstacles which the engineer

has to encounter. They inevitably lead to new reconnaissances

and new surveys. Deviations here and there are found to be expedient,

to save expense, now in first cost of construction, now in subsequent

cost of operating. The process of surveying does

not differ widely from that with which we may assume our readers

to be familiar in the laying out of town and farm boundaries and

of public highways, except in one important particular. In the

railroad survey the exact differences in level must be preserved

and respected. Every inequality must be noted. This is done by

the leveler, and is preserved by the profile map. Of these profile

maps there are two—one, the larger map, indicates the general

features of the route; the second and more detailed profile, or

series of profiles, preserves to the foot a careful record of

every inequality of ground over which the projected route is to

pass. These reports indicate exactly the obstacles which the engineer

has to encounter. They inevitably lead to new reconnaissances

and new surveys. Deviations here and there are found to be expedient,

to save expense, now in first cost of construction, now in subsequent

cost of operating.

At length the facts are all before the engineer-in-chief, and

he is prepared to make his report. It goes before the board of

directors. Its conclusions are scanned, its methods cross-examined,

its results subjected to the severest scrutiny. The counsel of

other and often rival engineers is called in. A thousand questions

must be raised, debated, determined, before any thing can be considered

settled. The road must deviate here to get the custom of a large

town or city, there to avoid grounds through which the right of

way would be more costly than a tunnel or a filling; now to tap

a rival or a cross railroad at the right spot, now to accommodate

some wealthy and influential patron, whose interest in the road

depends on making it at some point subservient to his own business.

If the engineer could only be permitted to ran his projected road

where it would be easiest built, his problem would be a simple

one; but he must also consider what will be the cost of carriage,

what will be expensive to maintain as well as to construct, where

he will get custom, and how he may avoid local opposition. A single

problem within our personal knowledge illustrates this phase of

the work. A railroad is under survey along the west bank of the

Hudson, which passes within a mile of our house. Five miles north

it reaches the city of Newburgh. If it run along the river-bank,

it must pay from half a million to a million of dollars for its

right of way. That necessity it can a-void only by tunneling the

hill on which the city is built. The city itself is evenly divided

in opinion. One half aver that a river railroad will spoil their

commerce; the other half assert that a tunnel railroad will spoil

their town. Whichever horn of the dilemma the company takes, it

will be unpopular with half a city. And its engineer and directors

must be wise not only to measure the comparative cost of the two

plans (itself hot an easy matter), but also wise to foresee the

effect, on both through and local traffic, of both plans. In short,

if the grown railroad is often whimsical and despotic, it does

but avenge itself for the whims and despotism which it suffers

from the public while it is yet in its infancy.

The railroad is projected; the

projector has secured the co-operation of sufficient capital to

enable a beginning to be made; it has been surveyed; the right

of way has been obtained; a charter hag been secured; it now remains

to construct the road. In the inception of railroad life this

was done by the company. Of the first railroad George Stephenson

was both surveyor and contractor. He laid out every foot of the

line of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, taking the sights

through the spirit-level with his own hands and eyes. The plans

of the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad he fought through Parliament

by his own indomitable will in the face of the opposition of wealth

and science and political power. And when at last the charter

was obtained and the work begun, he personally supervised it from

the beginning to the end, getting his breakfast of oatmeal with

his own hands, living on horseback, personally inspecting the

progress of every department of the work, supervising the pay-rolls

of the men, and perfecting with his own hand the working drawings.

But the growth of railroads has brought with it a division of

labor, and now the railroad corporation rarely or never constructs

its own line. This is done for the company by a railroad contractor.

Fifty years ago the farmer literally built his own house, mortised

the timber himself, perhaps cutting down the trees and squaring

them with his own broad-axe, and calling in his neighbors to assist

him with the, raising. The gentleman of to-day hires a builder

to construct his house and an architect to supervise it, and perhaps

never sees his edifice from the day the ground is first broken

until he is ready to move in. Railroad architecture is a distinct

art, and railroad building a distinct profession; and the company

as little thinks of personally constructing its own road as does

the merchant of personally supervising the erection of his own

house. The railroad is projected; the

projector has secured the co-operation of sufficient capital to

enable a beginning to be made; it has been surveyed; the right

of way has been obtained; a charter hag been secured; it now remains

to construct the road. In the inception of railroad life this

was done by the company. Of the first railroad George Stephenson

was both surveyor and contractor. He laid out every foot of the

line of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, taking the sights

through the spirit-level with his own hands and eyes. The plans

of the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad he fought through Parliament

by his own indomitable will in the face of the opposition of wealth

and science and political power. And when at last the charter

was obtained and the work begun, he personally supervised it from

the beginning to the end, getting his breakfast of oatmeal with

his own hands, living on horseback, personally inspecting the

progress of every department of the work, supervising the pay-rolls

of the men, and perfecting with his own hand the working drawings.

But the growth of railroads has brought with it a division of

labor, and now the railroad corporation rarely or never constructs

its own line. This is done for the company by a railroad contractor.

Fifty years ago the farmer literally built his own house, mortised

the timber himself, perhaps cutting down the trees and squaring

them with his own broad-axe, and calling in his neighbors to assist

him with the, raising. The gentleman of to-day hires a builder

to construct his house and an architect to supervise it, and perhaps

never sees his edifice from the day the ground is first broken

until he is ready to move in. Railroad architecture is a distinct

art, and railroad building a distinct profession; and the company

as little thinks of personally constructing its own road as does

the merchant of personally supervising the erection of his own

house.

The railroad contractor is eminently a practical man. He is

apt to be a self-made man. He is not unfrequently one who commenced

life with the spade, the pick-axe, and the wheelbarrow. He had

greater industry or greater shrewdness than his fellows, and became

the head of a gang of men. Then he took a small contract on his

own account, invested luckily in real estate along the line of

a projected railway, amassed a little capital, employed both capital

and practical experience to good advantage, and so gradually got

on in the world, till now, what with capital and credit, he stands

ready to undertake any work which the railroad capitalist desires

undertaken. He knows how many cubic feet of earth there are in

a hill, and how many it will take to fill up a valley. He has

a practiced eye for soils, and detects by a sort of intuition

where the, hard rock will be, and where the cutting will be an

easy one. Earth digging, blasting rocks, pumping, embanking, boring

and building tunnels, erecting bridges and culverts, are all familiar

operations with him. He possesses a larger or smaller stock of

wheelbarrows, picks, shovels, carts, earth wagons, and horses.

He lays temporary sleepers and light rails as the work, progresses,

and generally owns at least one or two locomotives and the necessary

dirt cars for dragging materials. He usually contracts for a section

of the road to be built at a fixed price, or at one which varies

within certain limits, according to the development of difficulties

as the work progresses. He often sublets to other contractors

his work in its detail. He sometimes makes a miscalculation and

loses a fortune, but his miscalculations are oftener on the credit

side of his ledger, and the result a fortune made. He has abundant

opportunities to make incidental profits, and he is not slow to

avail himself of them.

But he must not only have a practical knowledge of railroad

works, he must have a practical skill in managing railroad workers.

The first public works of importance in England were the canals.

The same class of workers that constructed them are now employed

in the construction of railroads. Their popular name is derived

from their original connection with the great system of inland

navigation which preceded and prepared for railways; they are

still termed navvies. The picture which Parliamentary reports

give us of the character of these men is not encouraging to those

who imagine that violence and corruption are a peculiar characteristic

of the American republic, and that the maintenance of a stronger

and more centralized government, like that of Great Britain, would

put an end to the brawls and lawlessness which they imagine to

be peculiar to a free country.

"Possessed of all the daring recklessness of the smuggler,"

says one English authority, Mr. Roscoe, "their ferocious

behavior can only be equaled by the brutality of their language.

It may be truly said their hand is against every man's, and before

they have been long located every man's hand is against theirs.

From being long known to each other they generally act in concert,

and put at defiance any local constabulary force; consequently

crimes of the most atrocious character were common, and robbery,

without any attempt at concealment, was an everyday occurrence."

Another English writer, Mr. Francis, is equally complimentary.

"The dread which such men as these spread throughout a rural

community was striking; nor was it without a cause. Depredations

among the farms and fields of the vicinity were frequent. They

injured every thing they approached. From their huts to that part

of the railway at which they worked, over corn or grass, tearing

down embankments, injuring young plantations, making gaps in hedges,

on they went, in one direct line, without regard to damage done

or property invaded. Game disappeared from the most sacred preserves;

gamekeepers were defied; and country gentlemen who had imprisoned

rustics by the dozen for violating the same law shrank in despair

from the railway 'navigator.' They often committed the most outrageous

acts in their drunken madness. Like dogs released from a week's

confinement, they ran about, and did not know what to do with

themselves. They defied the law, broke open prisons, released

their comrades, and slew policemen. The Scotch fought with the

Irish, and the Irish attacked the Scotch; while the rural peace-officers,

utterly inadequate to suppress the tumult, stood calmly by and

waited the result. When no work was required of them on the Sunday,

the most beautiful spots in England were desecrated by their presence.

Lounging in highways and byways, grouping together in lanes and

valleys, insolent and insulting, they were dreaded by the good

and welcomed by the bad. They left a sadness in the homes of many

whose sons they had vitiated and whose daughters they had dishonored.

Stones were thrown at passersby; women were personally abused,

and men were irritated. On the week-day, when their work was done,

the streets were void of all save their lawless visitors, and

of those who associated with them. They were regarded as savages;

and when it is remembered that large bodies of men, armed with

pitchforks and scythes, went out to do battle with those on another

line a few mile off, the feeling was justified by facts. Crime

of every description increased, but offense against the person

were most common. On one occasion hundreds of them were within

five minutes' march of each other ere the military and the magistrates

could get between them to repress their daring desires."

Christian philanthropy has not been oblivious of the condition

of these navvies, equally dreadful to themselves and dangerous

to society. Among the most interesting of all home mission work

is that which has been carried on by ladies of the highest culture

and refinement among these barbarians of civilization. The result

of improved systems of administration by Christian contractors

has been more effectual, however, than any direct and immediate

efforts by lay missionaries. Of these the work of Sir Morton Pete

may be mentioned as a type. He broke up the ticket system, i.e.,

the payment of wages by tickets, to be redeemed at the shop established

by the contractor. He paid all wages weekly. He opened the way

for house to house visitation by Christian clergymen and laymen.

He provided cleanly barracks in lieu of their huts of turf or

stone. He provided every one who could read with a Bible, and

organized clubs for mutual help in case of sickness or misfortune.

His example was followed by others; and though the English navvy

is not as yet a very creditable product of the civilization of

the nineteenth century, his character and condition have greatly

improved.

In this country the work of the pick and the barrow is largely

performed by Irish laborers. Their temporary villages are familiar

to every traveler on oar railroads. Their management requires,

on the part of the contractor, peculiar dexterity to avoid the

loss inevitable from wasted hours or misapplied energies. In brief,

the railroad contractor has under him an army of men without the

discipline of an army; he must exercise over them the control

of a general without being invested with a general's authority.

A condensed sketch of the difficulties and dangers attendant

upon the construction of a single line of railroad will better

illustrate the qualities which go to make a successful railroad

contractor, and the nature of his work, than any general description.

From Aspinwall to Panama there runs a line of railroad across

the isthmus which bears the latter name. It is not a long line;

its length is but forty-seven miles and a fraction. It is not

of difficult grades; its highest point is but two hundred and

sixty-three feet above tidewater, and its maximum grade is sixty

feet to a mile. Yet this single, and in size comparatively insignificant,

railroad involved the construction of one hundred and thirty-four

minor water-ways and thirty-six bridges, the latter ranging from

twelve to six hundred and twenty-five feet in length. The construction

of this road occupied five years and nine months. It commenced

at Aspinwall, in the heart of a swamp. The laborers had to clear

their way through the tangled underbrush of a tropical forest,

thigh-deep in water, subject at any moment to the attacks of alligators

and other not less dangerous though less formidable reptiles,

and enveloped in a cloud of flies and mosquitoes. Every workman

went to his labor veiled. Residence on the land was impossible.

An old brig anchored in the bay served the purpose of barracks

The constant motion of their prison-ship subjected the landsmen

to continued nausea by night, which but illy fitted them for toil

by day. The malarious fevers of the country converted their movable

barracks into a hospital ship. The two engineers in charge took

turns in the fever with their men, the least disabled rising from

the hospital bed to give place to his companion. Natives were

lazy, and would not work. Imported laborers from the North sickened

and died in such numbers that the work actually stopped for want

of hands. The importation of Chinese coolies proved an unsuccessful

experiment, for melancholy and suicide thinned out their ranks

almost as fast as malarious fever the ranks of their braver comrades.

The house of the first engineer was built on the tops of stumps

to keep it above the water-level. The freshets which swell the

Chagres River, sometimes in a single night to a height of forty

feet above its ordinary level, carried away the nearly completed

bridge which was to span it. Twice the road was contracted for,

and twice thrown back upon the company's hands, before it was

completed so far as to enable a locomotive to pass over it from

ocean to ocean.

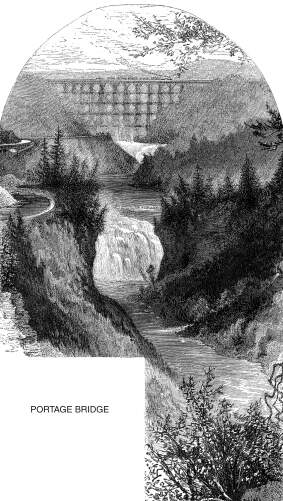

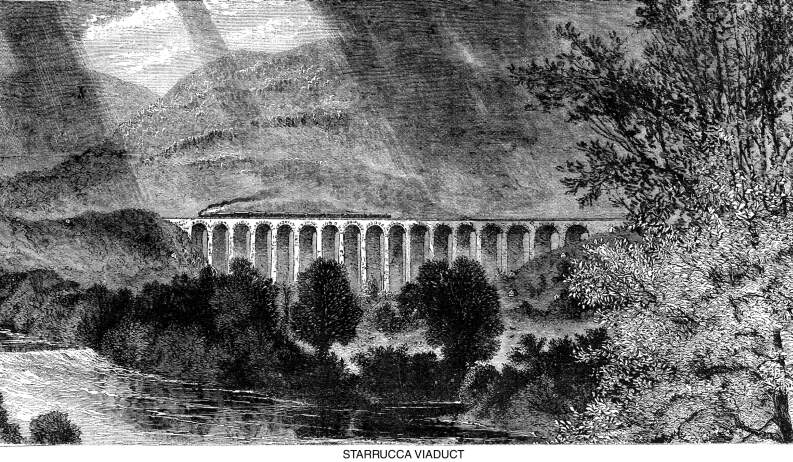

A distinct department of railroad engineering is the bridge-building.

This is now very generally undertaken, in the case of the larger

bridges, by separate corporations. Iron and stone are very generally

taking the place of wood as material for bridges on our best railways.

The character of the structure, whether iron or stone, whether

tubular, or suspension, or arched, depends upon the nature of

the chasm and the stream to be crossed. Our artist, from the many

illustrations of bridges which the Erie Railway affords, selects

two as samples of the problems to be solved by the railroad engineer,

and the methods of solving them. In the case of the Starrucca

Viaduct the problem was, in descending the western slope of the

mountain that intervenes between the Susquehanna and the Delaware

valleys, to take a flying leap across a vale a quarter of a mile

wide, from one hillside to another. The valley was quite too deep

and long to be filled up with an earth embankment, which, moreover,

would be in constant danger from rains and freshets. This problem

was solved by the construction of a stone viaduct 1200 feet long,

110 feet high, and consisting of eighteen arches with spans of

fifty feet. It is built of solid masonry, and appears to be as

durable as the everlasting hills themselves. The other problem

was involved in the necessity of crossing the Genesee River from

the high table-lands through which, at Portage, it cuts a deep

but narrow ravine. Its solution has given rise to one of the most

marvelous wooden bridges in the country. It is built on thirteen

stone piers set in the bed of the river, on which is reared a

mass of timber rising to the height of 234 feet. It is said to

be so constructed that any timber in the bridge can be removed

and replaced at pleasure. These illustrations are taken but as

types of the difficulties to be overcome by the railroad contractor,

and the methods of overcoming them. The difficulties are as diverse

as nature itself. To attempt any comprehensive account of bridges

and bridge-building would require not a paragraph, but a distinct

article.

In brief, then, it is the office of the railroad contractor

not only to pierce the hills, bridge the streams, cross the valleys,

construct the stations; not only must he be a bridge-builder,

a road-maker, and a practical mechanic; not only must he do his

work with ignorant, unskillful, often dishonest workmen, but he

must do it frequently in the heart of a wild, waste wilderness;

must transport thither his men, his tools, his provisions; must

erect the shelter and provide the necessaries of life for his

workmen; must keep up their failing courage with his own, and

must do all at the hazard not only of his purse, if his estimates

have deceived him, but at the hazard of his health and even of

his life.

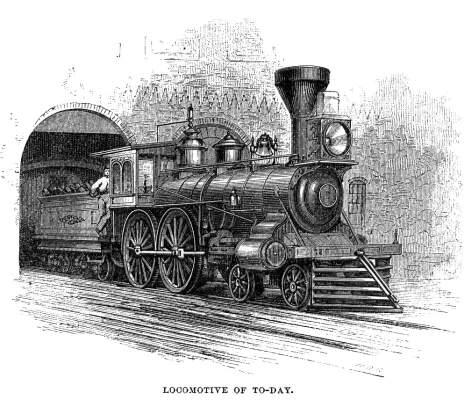

The railroad is built. The money has been raised. The cars

have been constructed, and the locomotives purchased. The railroad

is equipped and in running order. Let us glance rapidly at the

working of the road. For this purpose let us take the history

of a single train—say, the morning lightning express on the

Erie Railway from New York to Buffalo.

The first work of the day is to put the train together. Every

traveler has observed what a Wilderness of cars is scattered about

the stations at the termini of our large roads. These labyrinths

of railroad track are technically termed yards. At Hornellsville,

where the two forks of the Erie, Railway unite, one going to Buffalo,

the other to Dunkirk, there are over sixteen miles of these side

tracks. Through the heart of this yard the through track must

be kept always clear for passing trains.

From the cars which fill up the sidings each outgoing train

must be made up. In the case of the passenger express this is

a comparatively simple matter. The cars that have come in the

night before are re-arranged in a reverse order, are swept and

dusted and washed, and ready for use again. But the putting together

of a freight or mixed train is often a labor of great perplexity.

The cars which are intended to form such a train are often scattered

widely over the yard, one on the warehouse track, another on the

lumber side track, a third on the coal side track, a fourth among

the defective cars in the repair shop. These it is the business

of the yardsman to collect and organize into a train. For this

purpose there is placed under his orders a small switching engine,

with its engineer and fireman. From morning to night this yardsman

is on the move. He must know every inch of his depot yard, the

beginning and end of every side track, the peculiarities of every

switch, the time of the arrival and departure of every train,

the location of every car. He must know how to get them in place

with the least possible waste of time and energy, how to utilize

every moment, when he may safely cross this track, when run along

that. All day he is dodging in and out among tracks crowded with

cars, and often with passing trains, with nothing to guide him

but his 'own judgment, making his own time-table from minute to

minute, sometimes under exigencies such that a delay of a minute

results in a delay of hours. Next to the engineer and fireman,

there is perhaps no position of greater hazard or greater responsibility

than that of the yardsman.

The train is in its place. The early passengers are arriving

and getting themselves comfortably seated for their trip, while

the fireman is at work preparing his engine for the day's work.

Every engine has its own engineer and fireman. This is a necessity,

for an engine is like an organ; each new one must be learned anew

before one can play on it well. The most experienced engineer

can never use a new engine to good advantage. Did you never examine

the iron horse as it stands at the head of its train, impatient

to begin its day's journey? How it shines! What mirrors every

bit of burnished brass and polished steel! It must be groomed

like a horse, and the fireman is the groom. There is a hostler

besides, or gang of hostlers: wipers they call them. When the

engine comes in from its day's duty it goes straight to the engine-house,

and the wiper takes it in hand. Sooty, dusty, smoky, greasy, and

hot, it is delivered to him. He does not leave it until every

piece of metal shines again like French glass, or the reflecting

mirror of a great telescope. "Mighty unpleasant sort of 'work

it is until you get used to it. For you see an engine don't cool

down right off when it comes in, and it's pretty hot work handlin'

machinery just after a hundred-mile run, and the steam only just

let out. of the boiler." Yet, with all the hostler's care,

the groom is never satisfied; and after the morning fire is kindled,

and the tender is piled full of coal, and the water has been taken

on, you may see him still polishing away at portions of the machinery,

which might well be the envy of any housekeeper. All aboard! The

last look is taken by the careful engineer at his machinery, the

steam is tested, the signal-bell rings, and the train starts and

rolls slowly out of the station.

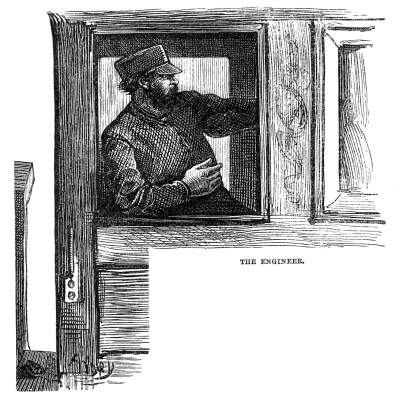

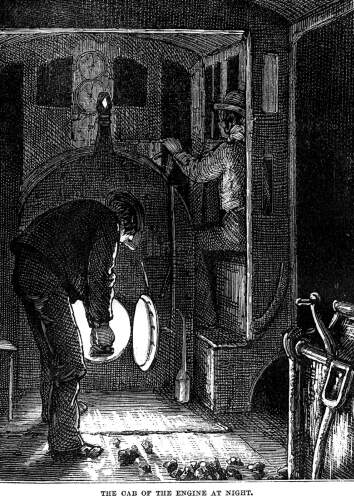

Come ride with me on the engine. It will be necessary to got

a special permit from the superintendent, for the strictest orders

forbid the engineer to carry any one on his engine without- Nay,

stop! It is nothing much to ride on an engine by day; but with

Mr. Joseph Taylor, himself a railway superintendent, for our companion,

we will try it on a night express.

"The Greyhound had a full head of steam on, and was blowing

off its safety-valve, making a deafening noise, and groaning with

the power within her. Carefully proceeding through the yard and

fast freight trains that would follow us, we soon left the station

lights behind, and plowed into the darkness and the storm.

"John Dobbs was one of the

oldest and best men on the road. It was his boast, and an honest

one, that during the sixteen years he had been driving on that

road, he had not cost the company a dollar for any negligence

or mistake of his. His record was clear. I sat and watched him

from the opposite side of the cab. He was rather tall, thin, and

of a nervous temperament; and although not even the smoke-stack

of the engine could be seen for the darkness and the drifting

snow, his piercing eye never wavered from its unsubstantial mark.

One hand on the throttle, the other on the reversing lever, he

stood erect and firm, intensely propelling his vision into the

abysmal darkness beyond. The Greyhound began to feel her feet;

her speed increased with every stroke of the piston head. Her

machinery quivered with its force; she leaped and reeled on each

defective joint, but her iron members held her firm. The fireman

never ceased to cast in the fuel, and the fierce flames darted

ardently through her brassy veins. Suddenly a scream from the

whistle, a quick, movement on the throttle-the fireman rushed

to the other side of the engine—a flash of light! We passed

a station and a freight train on the side track. More fuel into

the fire, and the Greyhound urged ahead, for now we, had a straight

piece of track before us. The storm abated, and the sky cleared.

The fireman produced from his pocket a small cutty-pipe, loaded

it with tobacco, lighted it with a puff or two, and without saying

a word, stuck it between John's teeth. John had taken about twenty

rapid whiffs, when the fireman, as unceremoniously as before,

transferred it to himself, and with a few fierce draws consumed

the load—a very impolite proceeding, but apparently part

of the discipline of the engine. Those few draws did both men

good. Johnny's grasp tightened on the throttle, and the fireman

with new energy threw in the wood. "John Dobbs was one of the

oldest and best men on the road. It was his boast, and an honest

one, that during the sixteen years he had been driving on that

road, he had not cost the company a dollar for any negligence

or mistake of his. His record was clear. I sat and watched him

from the opposite side of the cab. He was rather tall, thin, and

of a nervous temperament; and although not even the smoke-stack

of the engine could be seen for the darkness and the drifting

snow, his piercing eye never wavered from its unsubstantial mark.

One hand on the throttle, the other on the reversing lever, he

stood erect and firm, intensely propelling his vision into the

abysmal darkness beyond. The Greyhound began to feel her feet;

her speed increased with every stroke of the piston head. Her

machinery quivered with its force; she leaped and reeled on each

defective joint, but her iron members held her firm. The fireman

never ceased to cast in the fuel, and the fierce flames darted

ardently through her brassy veins. Suddenly a scream from the

whistle, a quick, movement on the throttle-the fireman rushed

to the other side of the engine—a flash of light! We passed

a station and a freight train on the side track. More fuel into

the fire, and the Greyhound urged ahead, for now we, had a straight

piece of track before us. The storm abated, and the sky cleared.

The fireman produced from his pocket a small cutty-pipe, loaded

it with tobacco, lighted it with a puff or two, and without saying

a word, stuck it between John's teeth. John had taken about twenty

rapid whiffs, when the fireman, as unceremoniously as before,

transferred it to himself, and with a few fierce draws consumed

the load—a very impolite proceeding, but apparently part

of the discipline of the engine. Those few draws did both men

good. Johnny's grasp tightened on the throttle, and the fireman

with new energy threw in the wood.

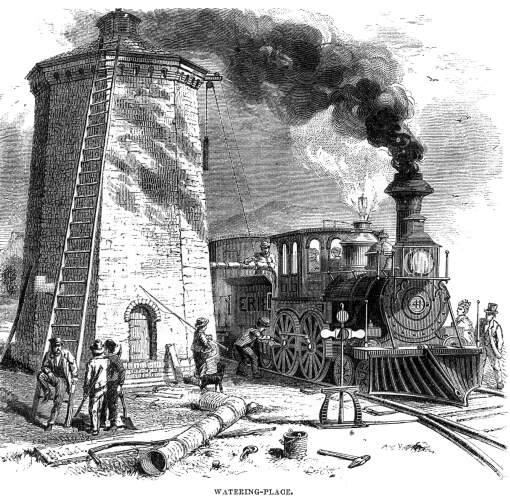

"We passed a few more stations and freight trains, and

at tremendous speed bounded from the level down a grade, the steepest

on the road. Steam was shut off, the fireman seized the wheel,

the whistle screamed for the brakes, and we finally came to a

stand right under the hose of a water-tank.

"'Engine-driving is trying work such weather as to-night,

Sir,' said Johnny, wiping the perspiration off his face with his

sleeve, 'when yon can't see your signal-lights, nor even your

smoke-stack, and you have to ran like mad on a bad track to make

up time so as not to lose connection. I tell yon it makes a man

sweat if he's as cold as a lump of ice. You have to go it blind.

You can't see if the switches are right. If trains you are to

pass have got into a side track, you can't make out any thing

till you're right into it. It's trying work on the mind, Sir,

is driving an engine. Such as us get very little sleep. The other

night my wife started up in bed and screamed as if she was being

murdered. "What are you doing?" she cried; and bless

your life, Sir, there was I pulling her slender arm with all my

might, while my foot was steadied against something else, trying

to reverse.'

"Over this dream at his wife's expense John Dobbs laughed

heartily; and as the tank was now filled with water, and a fresh

supply of wood was thrown on the tender, I wished him good-night,

preferring to complete my journey in the palace car at the rear."

With John's statement, "engine-driving is trying work

on the mind," we fully agree; in truth, no one who has not

ridden on the engine of a fast express by night, as we have done,

can imagine how trying it is. No wonder that the perpetual stimulant

to their nerves indurates their sensibilities; no wonder that,

as a class, railroad engineers are a "hard set." But

they are, with rare exceptions, noble, faithful, true, ready always

to sacrifice themselves to save their train. The true engineer

must be a man of ready resources and quick instincts. He must

have a mind that is stimulated, not dazed, by emergencies. He

must know how to think quick in the threatening of danger; when

to shut off steam and stop his train; when to put on more steam,

and ran the hazard of brushing the obstacle from the track with

such momentum as to save himself and his passengers. He must know

both his engine and his road, what she can bear, and what strain

the road puts upon her; where are the up grades where she needs

all her steam, where the down grades where all should be cut off;

where the crossings where the whistle or the bell must be sounded,

where the stations, and how to adjust his speed so as to stop

just at the right time and place. He must have ears and eyes and

thoughts all and always alert. He must not merely, like Davy Crockett,

be sure he is right and then go ahead, but be sure while he is

going ahead. He must look out not only for himself, but for others

as well, and never can be certain that the switchmen, on whose

fidelity his life and the lives of all his passengers depend,

have done their duty until he has safely passed the crossing or

the siding. In short, it is not only true of him that there is

always but a step between him and death, but it is always also

a step of one who is traveling thirty miles an hour. He must be

a practical mechanic, and be able to repair a break in his engine

without adequate tools. He must be a man of iron will, able to

withstand every influence and pressure in times of difficulty.

An express train on a single-track railroad comes to a station.

It is here to pass a down express on the same road. It is winter.

Both trains are behind time. The time-table gives the right of

way to the up train, but requires "caution." The word

is a vague one, and capable of various constructions. The engineer

resolves to wait where he is. The uneasy passengers wish him to

go on. Delegation after delegation urge him to do so. At length

a telegram is received. It reads simply, "Come ahead."

It is neither signed nor dated. The obstinate engineer will not

budge. The passengers hold an indignation meeting. Resolutions

are reported and carried, to be presented to the president of

the road. And just as the meeting is adjourning down comes an

extra engine, carrying no light, and running at sixty miles an

hour, to get doctors to attend the wounded on a "smash up"

of the down express eleven miles above. The obstinacy of the engineer

in giving a rigid construction to the one word "caution"

has saved the company another smash up, and the doctors more patients.

The thoughtful traveler will probably recollect more than one

instance in which the unreasonable public has similarly berated

a delaying train, and yet would have been equally quick to denounce

the careless engineer if he had yielded to its own unreasonable

demands.

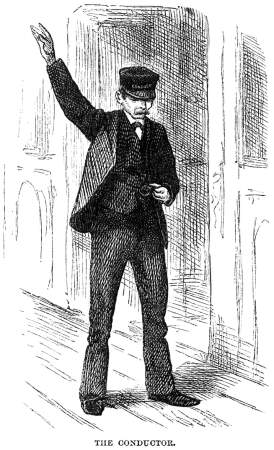

Scarcely less important in the

management of the train than the engineer is the conductor. He

is the captain: of all but the engine. He must be a good judge

of human nature, know how to be quick and yet courteous, firm

and yet affable. He must be able to detect the difference between

the real unfortunate who has lost his ticket and his purse together,

and the railroad swindler who makes a pretense of. loss serve

him the purpose of getting many a free ride. He must be equally

competent to help out with all her bundles the anxious lady from

Pumpkinville, who has never ridden in the cars before, and quick

to eject the brazen-faced defrauder who has no ticket, and no

notion of paying for one. He must be brave, for his courage is

often tested; forbearing, for his patience is sorely tried; and

faithful, because great trust is reposed in him. He must have

some practical knowledge to help him with expedients when accidents

occur, a ready judgment and nerve to act promptly in time of danger.

He must see that no time is lost at stations, carrying his timetable

in his head, and never misrecollecting its figures; have at his

fingers' ends all the intricate system of rules and regulations

issued by his superiors; keep on good terms with his engineer

and his brakemen, and control the latter without seeming to do

so. He must have an eye to the condition of the track, the trestles,

bridges, culverts, and embankments; must keep in mind and under

examination the brakes, couplings, and bell-ropes of his cars;

must inspect his train before starting, to see that his cars have

been carefully swept and dusted; must know that his watch accords

with railroad time; must be sure before starting that he is properly

provided with flags, signal-lamps, torpedoes, links, and pins.

He must keep on the alert for signals from the engineer, and from

stations on his route. He must keep in mind his passengers, see

that they got out at their right stations, or take their maledictions

in recompense for their own ignorance or inattention. He must

take up all tickets, and often must go through a long train twenty

or thirty times on each trip to make sure of the tickets of his

way-passengers. He must get out at every station, see his passengers

all off, and signal the train to proceed, being always in time

and never in haste. He must have plenty of leisure to answer all

the questions and respond to all the complaints which curious

or captious passengers have to prefer; and he must keep a perfect

account and render a perfect report of all tickets and fares collected.

In brief, the combined duties of captain, clerk, and steward of

a steam-ship fall upon the conductor of a first-class passenger

express. He travels usually from one hundred and fifty to two

hundred miles a day, often including the Sabbath, and his compensation

reaches the enormous sum of $1200 per year! Scarcely less important in the

management of the train than the engineer is the conductor. He

is the captain: of all but the engine. He must be a good judge

of human nature, know how to be quick and yet courteous, firm

and yet affable. He must be able to detect the difference between

the real unfortunate who has lost his ticket and his purse together,

and the railroad swindler who makes a pretense of. loss serve

him the purpose of getting many a free ride. He must be equally

competent to help out with all her bundles the anxious lady from

Pumpkinville, who has never ridden in the cars before, and quick

to eject the brazen-faced defrauder who has no ticket, and no

notion of paying for one. He must be brave, for his courage is

often tested; forbearing, for his patience is sorely tried; and

faithful, because great trust is reposed in him. He must have

some practical knowledge to help him with expedients when accidents

occur, a ready judgment and nerve to act promptly in time of danger.

He must see that no time is lost at stations, carrying his timetable

in his head, and never misrecollecting its figures; have at his

fingers' ends all the intricate system of rules and regulations

issued by his superiors; keep on good terms with his engineer

and his brakemen, and control the latter without seeming to do

so. He must have an eye to the condition of the track, the trestles,

bridges, culverts, and embankments; must keep in mind and under

examination the brakes, couplings, and bell-ropes of his cars;

must inspect his train before starting, to see that his cars have

been carefully swept and dusted; must know that his watch accords

with railroad time; must be sure before starting that he is properly

provided with flags, signal-lamps, torpedoes, links, and pins.

He must keep on the alert for signals from the engineer, and from

stations on his route. He must keep in mind his passengers, see

that they got out at their right stations, or take their maledictions

in recompense for their own ignorance or inattention. He must

take up all tickets, and often must go through a long train twenty

or thirty times on each trip to make sure of the tickets of his

way-passengers. He must get out at every station, see his passengers

all off, and signal the train to proceed, being always in time

and never in haste. He must have plenty of leisure to answer all

the questions and respond to all the complaints which curious

or captious passengers have to prefer; and he must keep a perfect

account and render a perfect report of all tickets and fares collected.

In brief, the combined duties of captain, clerk, and steward of

a steam-ship fall upon the conductor of a first-class passenger

express. He travels usually from one hundred and fifty to two

hundred miles a day, often including the Sabbath, and his compensation

reaches the enormous sum of $1200 per year!

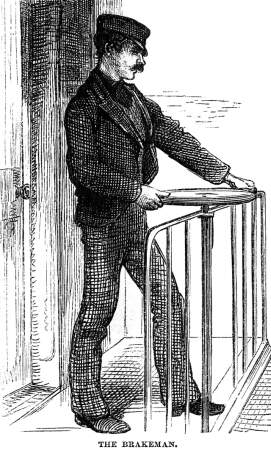

Since the invention of the Westinghouse

air brake the office of the brakeman has sensibly decreased in

importance. This brake is operated by compressed air, which is

driven through tubes beneath the cars by the steam from the engine.

These tubes are coupled when the train is made up. The whole is

operated as one brake from the engine by the fireman. It places

the whole train completely under the engineer's control. The through

fast express trains on our great trunk roads are now, we believe,

generally supplied with this contrivance. But the train can not

spare the brakeman. He stuffs fuel into the stove at the request

of the passenger who is too cold, and opens the window at the

request of the passenger who is too hot. He unlocks the seat and

turns it over for the mother who wants to convert it into a lounge

for her tired child to sleep on. He opens the door and shouts

in stentorian tones some unintelligible words at the approach

to every station. He occasionally makes announcements, but as

he usually does this when the train is in full motion, and as

he has never been taught to articulate very distinctly, the passenger

who is curious to know the meaning of his address has always to

ask for its private repetition. He is always on hand to help passengers

off the platform. Of men he is decidedly oblivious; he is a ladies'

man, and the assiduity of his attentions is generally in the direct

ratio of their youth and beauty. When he can inveigle a young

lady on to the platform before the train has quite reached a stop,

and can protect her from falling by gently encircling her waist

with his strong arm, he is perfectly happy. A virtuous brakeman

is never without his reward. Since the invention of the Westinghouse

air brake the office of the brakeman has sensibly decreased in

importance. This brake is operated by compressed air, which is

driven through tubes beneath the cars by the steam from the engine.

These tubes are coupled when the train is made up. The whole is

operated as one brake from the engine by the fireman. It places

the whole train completely under the engineer's control. The through

fast express trains on our great trunk roads are now, we believe,

generally supplied with this contrivance. But the train can not

spare the brakeman. He stuffs fuel into the stove at the request

of the passenger who is too cold, and opens the window at the

request of the passenger who is too hot. He unlocks the seat and

turns it over for the mother who wants to convert it into a lounge