|

AMERICAN INDUSTRIES—Baldwin

Locomotive Works — Scientific American—May

31, 1884

THE MANUFACTURE OF LOCOMOTIVES.

It has been a common remark, in connection with any disturbance

of the money market since the war, that the country was building

railways too fast. Ten million dollars a day was the estimated

cash outlay on this account, according to Poor's Manual, for the

three years up to the close of 1882, with a capitalization of

nearly double this amount. Yet it was a felicitous comparison

which suggested that even this great investment hardly exceeded

that which either of three of the great powers in Europe annually

expended in the maintenance of armies and iron clads in times

of peace. The nation, as a whole, may therefore be truly said

to have been putting only a moderate portion or its surplus into

this most effective way or hastening the further development of

its own resources, and though this may have afforded the opportunity,

it has been in no way the cause, of any Wall Street panic.

Side by side with this enterprise in railroad building, at

once caused by and promoting it, has been the wonderful growth

of every industry pertaining to the equipment and operation of

railroads. There were a few locomotives imported in the infancy

or railroad building here, which met with only indifferent success,

but our own inventors and mechanics early began to take the lead

in this branch of manufacture and in car building, which they

have ever since held. The locomotive of today is one of

the most wonderful of all the products of man's skill, and has

reached a point of perfection from which it seems hardly possible

to attain further progress, so long as we obtain power from coal

and wood according to principles now understood.

It is in itself an epitome of modern technical skill, representing

almost numberless inventions, and the illustrations we to day

give, of the largest locomotive manufactory in the world, speak

also of a history of its development during half a century.

The Baldwin Locomotive Works, at Philadelphia, had a humble

beginning. Matthias W. Baldwin, the founder, was a jeweler and

silversmith, who, in 1825, formed a partnership with a machinist,

and engaged in the manufacture of bookbinders' tools and cylinders

for calico printing. Mr. Baldwin then designed and constructed

for his own use a small stationary engine, the workmanship of

which was so excellent and its efficiency so great that he was

solicited to build others like it for various parties, and thus

led to turn his attention to steam engineering. In 1831 he built

a miniature locomotive, for exhibition, which was so much of a

success that he that year received an order from a railway company

for a locomotive to run on a short line to the suburbs of Philadelphia.

The difficulties attending the execution of this first order were

such as our mechanics now cannot easily comprehend. Tools were

not easily obtainable; the cylinders were bored by a chisel fixed

in a block of wood and turned by hand; the workmen had to be taught

how to do nearly all the work; and Mr. Baldwin himself did a great

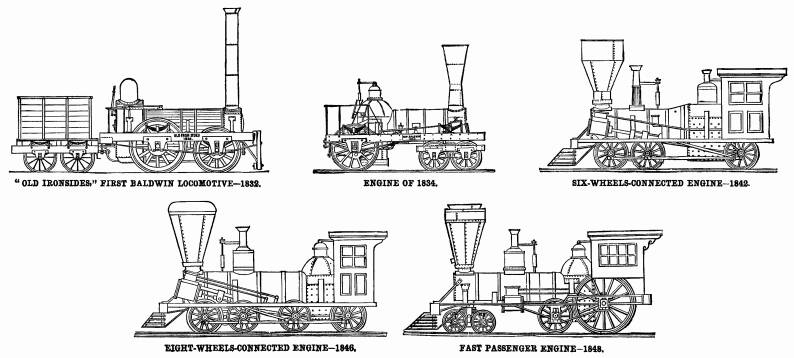

deal of it with his own hands. It was under such circumstances

that his first locomotive, christened Old Ironsides, was completed

and tried on the road, November 23, 1832. It was at once put in

active service, and did duty for over a score of years. It was

a four-wheeled engine, weighing a little over five tons; the driving

wheels were 54 inches in diameter, and the cylinders 9½

inches in diameter by 18 inches stroke. The wheels were of heavy

cast iron hubs, with wooden spokes and rims, and wrought iron

tires, and the frame was of wood placed outside the wheels.

The boiler was 30 inches in diameter, and bad seventy-two copper

flues 1½ inches in diameter and 7 feet long. The price

of the engine was to have been $4,000, but only $3,500 was actually

paid for it by the railroad company. The Ironsides attained a

speed of thirty miles an hour, with the usual train, and was said

at the time to be superior to English locomotives then made, on

account of its "light weight, small bulk, and the simplicity

of her working machinery."

In February, 1834, Mr. Baldwin completed his second locomotive,

for a railroad in South Carolina. In it was embodied a "half

crank" improvement which he had obtained a patent for, by

which the boiler could be made larger and placed lower. The driving

wheels were made of solid bell metal, the combined wood and iron

wheels previously used having proved objectionable, and Mr. Baldwin

obtained a patent for a cast brass wheel, his idea being that

by varying the hardness of the metal the adhesion of the drivers

on the rail could be increased or diminished. The brass wheels

soon wore out, and no others of the kind were made, but the general

features of this second locomotive were followed in most of the

machines built by Mr. Baldwin for several years. The valve motion

was given by a single fixed eccentric for each cylinder.

Five locomotives were built in 1834, when the new business

was fairly under way, and in 1835 a building was erected for the

works, which occupies a part of the present site on Broad Street,

this original structure now forming the storeroom, boiler shop,

and principal machine shops. All these engines built in 1834 had

several patented inventions of Mr. Baldwin. They had the half

crank, ground joints for steam pipes, and the pump formed in the

guide bar, four-wheeled truck in front, and a single pair of drivers

back of the fire box. The English engine builders were then making

steam pipe joints with canvas and red lead, which would only permit

of their carrying a pressure of some sixty pounds of steam, while

Mr. Baldwin's locomotives were worked up to twice that pressure.

In the six years from 1835 to 1840, inclusive, 152 engines

were turned out at the works, and, though there were not many

changes in design, there was a call for larger engines. Three

sizes were built: 12½ by 16 inches cylinder, weighing 26,000

pounds; 12 by 16 inches cylinder, weighing 23,000 pounds; and

10½ by 16 inches cylinder, weighing 20,000 pounds.

In 1842, Mr. Baldwin patented what has since been considered

the greatest of his improvements in engine building, the six-wheel

connected locomotive, with the four front drivers combined in

a flexible truck. The first engine of this class weighed twelve

tons, and its performance was so successful that orders for similar

ones came in rapidly. The adoption of this plan of building also

led to the immediate increase of the weight of locomotives, and

in 1844 several were built weighing eighteen and twenty tons.

In 1845 the present design of four drivers and a four-wheeled

truck was adopted. At first the half crank was used; then horizontal

cylinders inclosed in the chimney seat and working a full-crank

axle, and eventually outside cylinders with outside connections.

In 1848, Mr. Baldwin took a contract to build for the Vermont

Central Railroad, for $10,000, a locomotive which would run with

a passenger train at a speed of sixty miles an hour. It had one

pair of driving wheels six and a half feet in diameter back of

the fire-box, and the cylinders were seventeen and a quarter inches

in diameter and twenty inches stroke. This engine was used on

the road several years, and the officers stated that it could

be started from a state of rest and run a mile in forty-three

seconds.

A prominent feature in the conduct of the business of the Baldwin

locomotive works is the extensive use of standard gauges and templets.

An independent department of the works, having a separate foreman

and a force of skilled workmen, with special tools, is organized

as the department of standard gauges, where gauges and templets

for every description of work are made and kept. The original

templets are kept as standards, and never used in the work itself,

but from them exact duplicates are made, which are issued to the

foremen of the different departments. The working gauges are compared

with the standards at regular intervals, in order to secure absolute

uniformity in every detail. Frames are planed and slotted to gauges,

and drilled to steel-bushed templets; cylinders are bored and

planed, and steam ports, with valves and steam chests, finished

and fitted to gauges. Tires are bored, centers turned, axles finished,

and cross-heads, guides, guide-bearers, pistons, connecting and

parallel rods, planed, slotted, or finished by the same method.

Every bolt about an engine is made to a gauge, and every hole

drilled and reamed to a templet, so as to secure uniformity and

interchangeableness of parts. This system had been developed and

perfected previous to the death of Mr. Baldwin, which occurred

in 1866.

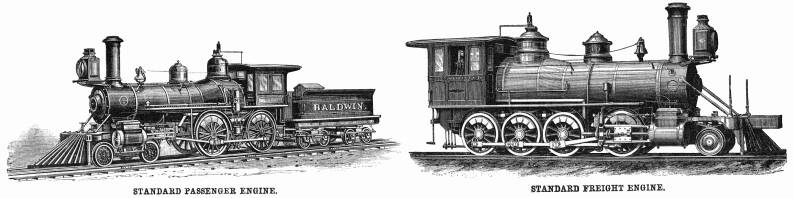

The heaviest locomotive built at the works up to 1878, and

one of the heaviest ever built, was for the New Mexico and Southern

Pacific. It was of the "Consolidation" type; cylinders,

20 by 26 inches; driving wheels, 42 inches diameter, four pairs

connected; one pair truck wheels, 30 inches diameter; capacity

of water tank on boiler, 1,200 gallons, and of tender 2,500 gallons;

weight of engine, including water in tank, 115,000 pounds, and

weight on driving wheels 100,000 pounds.

The works, when running full, give employment to 3,000 hands,

and are capable of turning out 600 locomotives a year. Their actual

production for the last forty-two years has been as follows:

There are about 15,000 locomotives of all kinds in actual use

in the United States, the Pennsylvania Railroad leading with over

1,100, the New York Central coming next with 700, after which

come in order Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul, Baltimore and

Ohio, Erie, Chicago and Northwestern, Philadelphia and Reading,

and Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy—each with more than 500.

The Baldwin locomotive works has furnished a large proportion

of all these, but it has further made locomotives for almost every

country in the world. Russia has been a liberal purchaser, many

have gone to Central Europe, Australia has many of these American

engines, and South American roads have been principally supplied

from here.

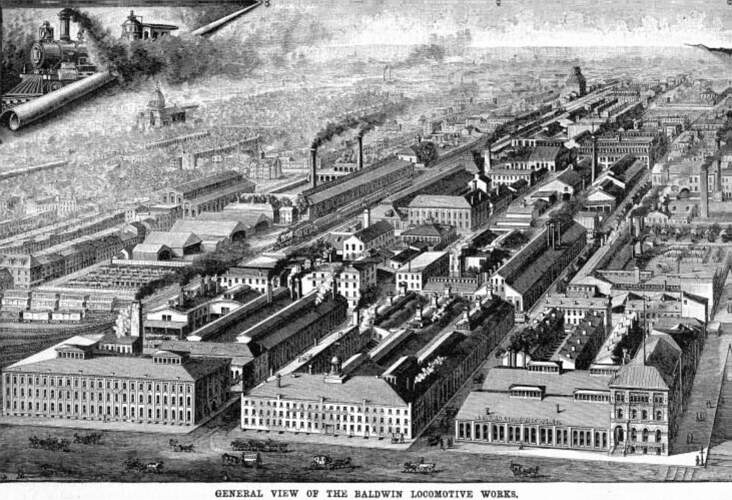

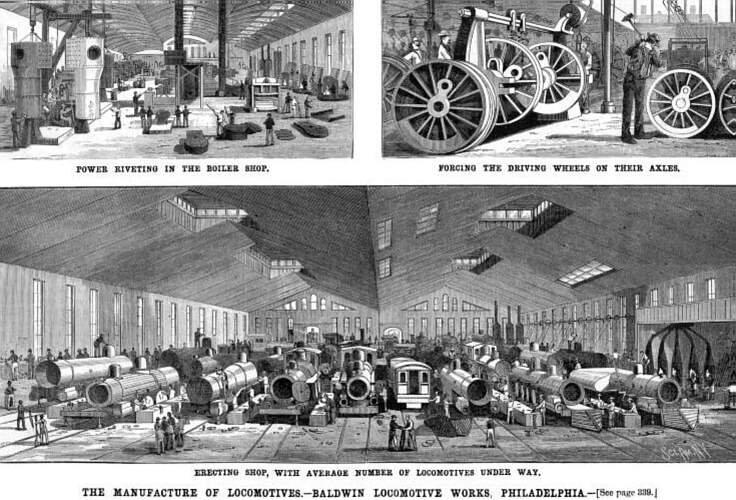

The area covered by the works, on Broad Street, Philadelphia,

is rather more than nine acres. The view of the erecting shop

shows a great number of locomotives under way, but it is only

a faithful representation of the scene when our artist visited

the works, and gives only a fair idea of the average amount of

work in hand. This immense production gives the firm great advantages

in the filling of orders promptly, and the fact that all parts

are made interchangeable renders it possible for the purchaser

to keep the expenses for repairs at a minimum, by keeping duplicate

parts of pieces likely to break or wear out, or by ordering them

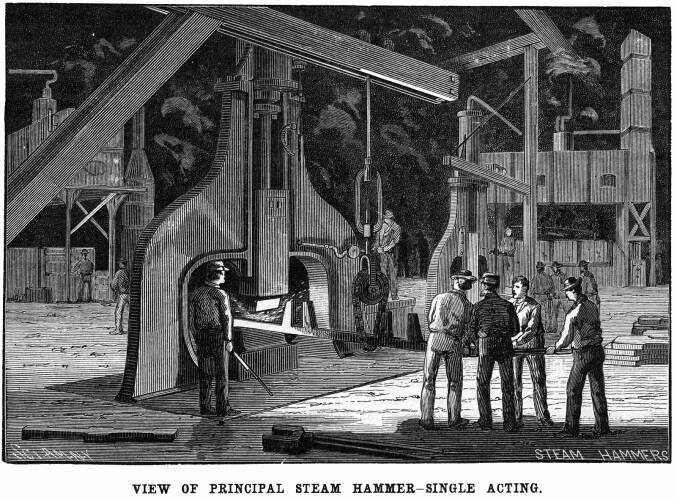

as needed from the works. In the boiler shop, while there is some

riveting done by hand, power machines are mostly used therefor,

and the view of the wheel department illustrates the forcing of

the driving wheels upon their axles. The steam hammer shown is

one of several of the same kind in the works. It is single acting,

7,000 pounds weight of ram, drop four and a half feet, and piston

rod five inches diameter.

The firm as now constituted was formed in 1873, under the style

of Burnham, Parry, Williams & Co.

Build a Locomotive

| Contents Page

|