The Breakdown of Our Railway

Transportation

Neglect of Motive Power

Maintenance the Key to the Situation

Neglect of Motive Power

Maintenance the Key to the Situation

Scientific American—June 1, 1918

WE who ride in the "varnished

cars" are often at a loss to understand the frequently published

reports that the railroads are unable to handle the supplies that

are not only essential to the existence of the inhabitants of

our cities and towns but as well as for our armies both abroad

and at home. At every terminal point, and scattered at frequent

intervals along the thousands of miles of tracks all over the

country, are seen herds of great locomotives, hissing with steam,

the embodiment of vast pent up power. The boiler is there, the

wheels are all there, nothing seems to be missing from the machinery.

Why can't they get the trains over the road? WE who ride in the "varnished

cars" are often at a loss to understand the frequently published

reports that the railroads are unable to handle the supplies that

are not only essential to the existence of the inhabitants of

our cities and towns but as well as for our armies both abroad

and at home. At every terminal point, and scattered at frequent

intervals along the thousands of miles of tracks all over the

country, are seen herds of great locomotives, hissing with steam,

the embodiment of vast pent up power. The boiler is there, the

wheels are all there, nothing seems to be missing from the machinery.

Why can't they get the trains over the road?

Unfortunately this is also the view taken for many years by

the officials who have been in charge of our railway management.

They are wise in the intricacies of the stock market; they provide

wonderful and luxurious trains for the transportation of their

passengers, but when it comes to the grimy details of the machinery

that keeps the trains moving they have shown most remarkable obtuseness.

The passenger trains are the ones that make the show to the public,

and no expense is spared on them; but it is the unpicturesque

freight train that earns the money, and, strange to say, this

is the direction in which petty economies have been carried to

the extreme, and as long as a freight engine can turn a wheel

it is kept at work, whether it is doing the duty intended, and

of which it is capable, or not.

The province of a railroad is to

sell transportation, particularly the transportation of freight,

and to enable it to perform its vital function effectively the

operating machinery should be kept in efficient condition. How

this is not done is in a measure indicated by a report made by

inspectors of the Interstate Commerce Commission last winter;

and one example taken from this report will indicate what inefficiency

in this direction means. At a roundhouse of one road there were

22 locomotives outside waiting for repairs. One of these had been

waiting for four days; and assuming that this engine was capable

of hauling 1,200 tons, when in good order, which is undoubtedly

far below its actual capacity, and also assuming that it would

cover 65 miles a day with its train, which is also a conservative

figure, the delay of four days would mean that the road lost a

service that would have moved 312,000 tons one mile; ton-miles

being the railroad standard for calculating work done. Stating

the case in another way, a mechanical plant costing in the neighborhood

of $50,000 was kept idle four days because the owners had not

provided the facilities for keeping it in operation. Any business

man with manufacturing experience will appreciate what this means.

This of course is considering only the unnecessary waiting time,

without taking into account the time required for the actual repair

work. The province of a railroad is to

sell transportation, particularly the transportation of freight,

and to enable it to perform its vital function effectively the

operating machinery should be kept in efficient condition. How

this is not done is in a measure indicated by a report made by

inspectors of the Interstate Commerce Commission last winter;

and one example taken from this report will indicate what inefficiency

in this direction means. At a roundhouse of one road there were

22 locomotives outside waiting for repairs. One of these had been

waiting for four days; and assuming that this engine was capable

of hauling 1,200 tons, when in good order, which is undoubtedly

far below its actual capacity, and also assuming that it would

cover 65 miles a day with its train, which is also a conservative

figure, the delay of four days would mean that the road lost a

service that would have moved 312,000 tons one mile; ton-miles

being the railroad standard for calculating work done. Stating

the case in another way, a mechanical plant costing in the neighborhood

of $50,000 was kept idle four days because the owners had not

provided the facilities for keeping it in operation. Any business

man with manufacturing experience will appreciate what this means.

This of course is considering only the unnecessary waiting time,

without taking into account the time required for the actual repair

work.

Of course this may be said to be an extreme case, but nevertheless

it is a picture of what has been going on in railroad practice

for years, as can be proven by consulting the files of any publication

devoted to railroad matters for as far back as anyone cares to

go. Of course there are exceptions to this rule, but they are

surprisingly few considering the great number of roads in this

country and the enormous amount of business they are required

to handle. As a rule, however, the provision made for maintaining

the operative machinery would be considered by men on other lines

of business who use machinery as preposterously inadequate.

We constantly read glowing statements

of the enterprise of the railroads in buying big engines to handle

their rapidly growing business, but we hear little of the fact

that these same roads have made absolutely no provision for maintaining

these great and enormously expensive machines. Take the case of

the roundhouse, where locomotives are housed for cleaning and

adjustment after a run; very few can be found that will accommodate

one of the newer large engines that are now so generally used,

and as a consequence the doors cannot be closed to protect either

the men or the machine while this necessary work is being done,

and in winter weather both are exposed to bitter cold and driving

snow and rain. Indeed, in many cases it has been necessary to

break out a large portion of the front walls to enable the engine

to get in at all. Under these conditions good work cannot be expected.

The repair shops proper are equally inadequate both in size and

equipment. In a recent issue of the Railway Age, the leading publication

devoted to railroad matters, the statement was made that "One

road owning over 2,000 locomotives estimates that its repair facilities

can only be brought up to the proper standard by an expenditure

of over $10,000,000. Another road operating about 1,500 locomotives

has only repair facilities for 750 and these are old shops with

inadequate facilities." The same authority estimates that

60 per cent of the locomotives of the country will have to go

through the shops for repairs this summer, if we are to go into

the next winter in proper shape; but how this is to be done no

one can tell. We constantly read glowing statements

of the enterprise of the railroads in buying big engines to handle

their rapidly growing business, but we hear little of the fact

that these same roads have made absolutely no provision for maintaining

these great and enormously expensive machines. Take the case of

the roundhouse, where locomotives are housed for cleaning and

adjustment after a run; very few can be found that will accommodate

one of the newer large engines that are now so generally used,

and as a consequence the doors cannot be closed to protect either

the men or the machine while this necessary work is being done,

and in winter weather both are exposed to bitter cold and driving

snow and rain. Indeed, in many cases it has been necessary to

break out a large portion of the front walls to enable the engine

to get in at all. Under these conditions good work cannot be expected.

The repair shops proper are equally inadequate both in size and

equipment. In a recent issue of the Railway Age, the leading publication

devoted to railroad matters, the statement was made that "One

road owning over 2,000 locomotives estimates that its repair facilities

can only be brought up to the proper standard by an expenditure

of over $10,000,000. Another road operating about 1,500 locomotives

has only repair facilities for 750 and these are old shops with

inadequate facilities." The same authority estimates that

60 per cent of the locomotives of the country will have to go

through the shops for repairs this summer, if we are to go into

the next winter in proper shape; but how this is to be done no

one can tell.

The lack of shop and housing facilities carries many evils

in its train. As there is not room enough in the shops for all

the engines needing repairs all but the heaviest work is usually

done out of doors, on the open tracks and in winter weather it

is evident that all work of this kind must be practically suspended.

Moreover, in such track work at least 50 per cent of the workman's

time is wasted in going back and forth to the shop for tools,

material and the machine work that must be done in the shop, and

such work as is done cannot be properly supervised. Still another

objection to this practice is that no first-class mechanic will

undertake this kind of work, for a competent man can always find

employment inside where he will not have to undergo the discomfort

and inconvenience of an open railroad yard.

The locomotive repair shop is a standing tribute to the incapacity

of those responsible for it. It has already been pointed out that

on the great majority of our roads these shops are far too small

for the work that ought to be done; but in addition to that, as

a rule, the machinery with which they are equipped is ridiculously

inadequate, and hopelessly antiquated, with the result that the

work done in them is excessively costly. Considered as a whole,

the system of locomotive maintenance found on the majority of

the railroads in this country could not be more inefficient and

wasteful.

With adequate maintenance equipment for the motive power more

work and better work could be done with a smaller number of engines;

and the addition of large numbers of new locomotives not only

adds to the congestion of the yards, but throws new burdens on

the already inadequate shops. Inadequate repair facilities does

not mean that heavy losses are incurred only through excessive

time required for the repairs, but there are additional losses

every day a defective locomotive is kept in service owing to its

inability to haul full loads, delays in getting over the road

and consequent delays of other trains and general disorganization

of the traffic of the road. It can readily be seen that the saving,

if it can be called saving, of a few thousands in repair facilities

results, in the loss of millions of dollars in the legitimate

earnings of the railroads of the country, and this has been going

on for years.

The failure of our railroads to

adequately perform the functions expected of them is, however,

not entirely the result of neglected motive power, for similar

conditions prevail in most everything connected with freight transportation.

The maintenance of freight cars has been slighted to a surprising

extent, and terminal facilities have by no means kept pace with

the increasing necessities of commerce; although in this matter

a considerable portion of the congestion may be attributed to

the custom of permitting consignees to delay unloading cars for

extended periods, thus using them for storage purposes instead

of promptly releasing them to perform their proper function as

transporters of freight. This latter abuse, it may be remarked,

has grown up as a result of competition between different roads

to secure business by extending privileges to shippers. A typical

case of this kind was recently noted in New York, where a number

of cars was reconsigned five times, each consignee holding the

shipment in the cars until he could resell the goods, the result

being that the cars were held out of legitimate service for several

months. The failure of our railroads to

adequately perform the functions expected of them is, however,

not entirely the result of neglected motive power, for similar

conditions prevail in most everything connected with freight transportation.

The maintenance of freight cars has been slighted to a surprising

extent, and terminal facilities have by no means kept pace with

the increasing necessities of commerce; although in this matter

a considerable portion of the congestion may be attributed to

the custom of permitting consignees to delay unloading cars for

extended periods, thus using them for storage purposes instead

of promptly releasing them to perform their proper function as

transporters of freight. This latter abuse, it may be remarked,

has grown up as a result of competition between different roads

to secure business by extending privileges to shippers. A typical

case of this kind was recently noted in New York, where a number

of cars was reconsigned five times, each consignee holding the

shipment in the cars until he could resell the goods, the result

being that the cars were held out of legitimate service for several

months.

That such conditions should exist may seem surprising to most

people, who have been regaled with glowing accounts of the phenomenal

abilities of the officials who control our roads, and the wonderful

growth of the roads they operate. As a matter of fact growth of

our roads has been due entirely to the growing demands of the

commerce of our country, and in spite of their methods of management.

Without question, there have been many men of unusual natural

ability in charge of the railways of this country; but results

tell their own story, and the serious breakdown of our railroads

under the emergency demands of war conditions shows conclusively

a great lack of scientific and efficient management, not for the

time being, but extending back many years. Indeed, our railroads

offer a great field for the efficiency expert.

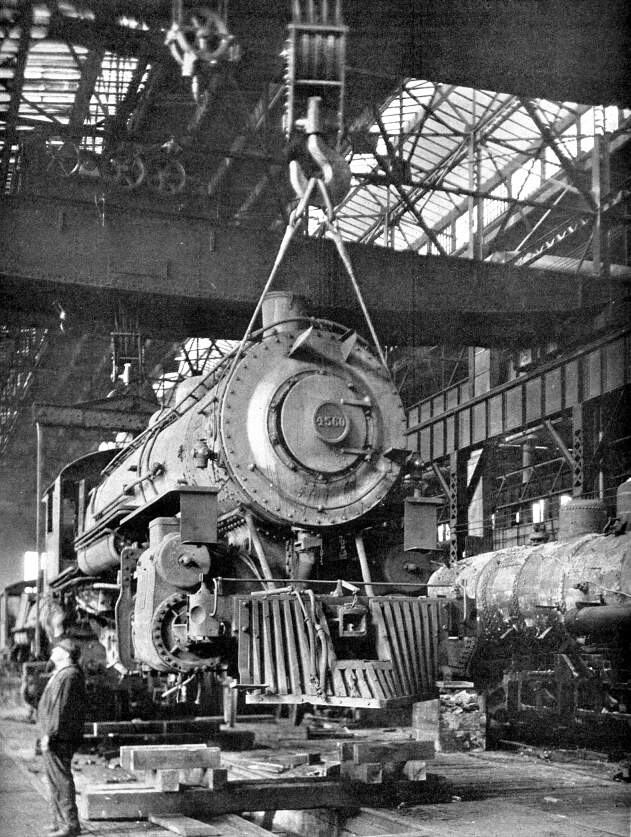

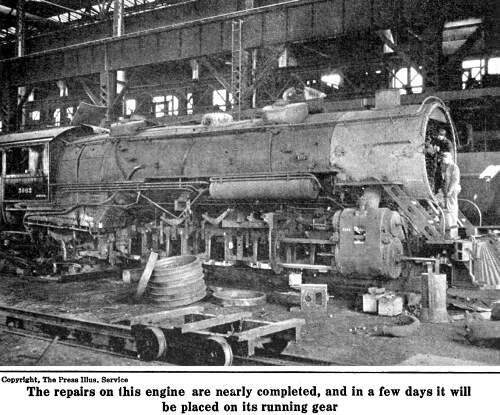

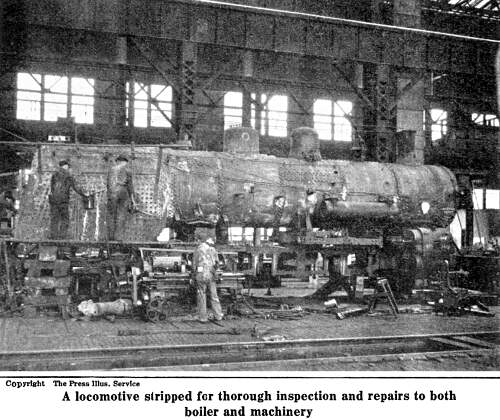

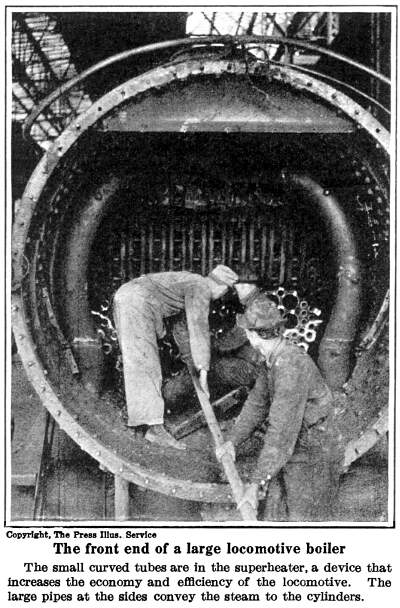

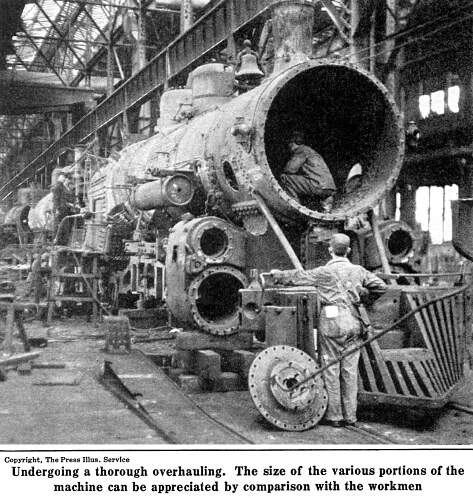

That some of our railroads have provided modern facilities

for caring for their motive power is shown by the accompanying

illustrations, which indicate the character of the work that has

frequently to be done, and which give an idea of the magnitude

of the task.

Build a Locomotive

| Contents Page

|