|

||||||

| ||||||

|

This story originally appeared in Railroad Magazine-originally Railroad Man's Magazine, September, 1943 by Popular Publications. This story has been reprinted with consent from Carstens Publications. Rails Rust in the Catskills By H. H. GROSS SHE WAS ALWAYS going to be a great road some day," pronounced Harry Miller, one-time general freight and passenger agent on the now abandoned Delaware & Northern.

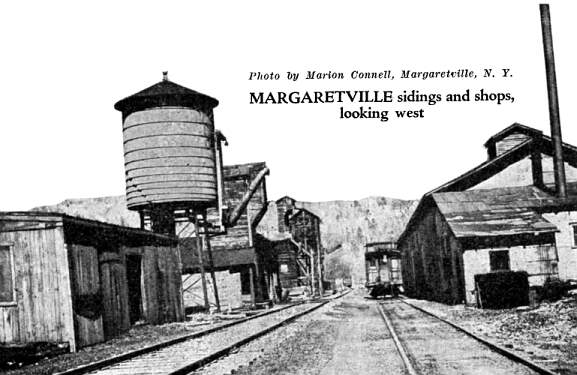

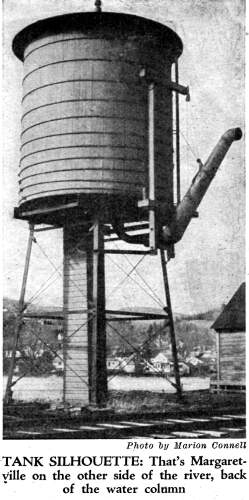

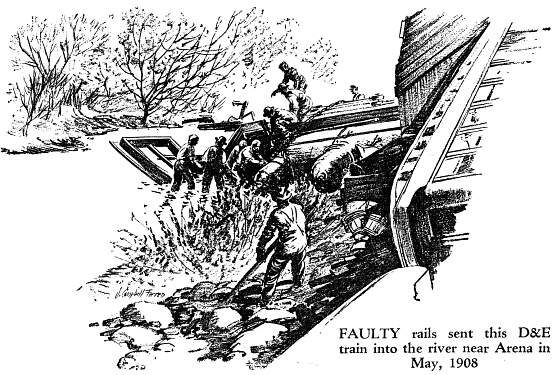

James Welch, dispatcher in 1906 when engine No. 1 first arrived in Downsville, N. Y., and superintendent of the line from 1911 to the hour in October, 1942, when the last train puffed over the winding rails between East Branch and Arkville, N. Y., shook his head. "We never had enough working capital." It was a Sunday afternoon in late summer. The four old, rails had strolled across the bridge that centers State Highway 28 through the little Catskill town of Margaretville and down past the depot to take a final survey of the D&N's rolling stock. Shortly, Hyman Michaels of Chicago would begin to lift the rusted track and haul away the rotted old coaches and flat cars for scrap. Standing below the engine house and coaling station, looking west with the East Branch of the Delaware and the scattered houses of Margaretville to their left, the old-timers faced the deserted sidings and shops. Sundown was red on the crenellated heads of old Pakatakan Mountain. Harry Eckert, brass pounder and dispatcher through the thirty-six years the road operated as the last independent railway in New York state, joined in the talk. "We worked like devils, fought them all, the O&W the D&H, even the New York Central. Not a man on the road didn't do ten jobs, let alone his own. Snow slides when our engine was buried so deep we siphoned snow into the tank to keep up steam so's not to freeze to death before we could dig out—thirty-six hours of that one time; floods, washouts, receiverships, we went through 'em all; and still the big time was coming, we thought." "We had our fun," said, Ira Terry, now with the New York, Ontario & Western. "It was a great game." Harry Eckert summed it up: "A great dream." THE dream first took shape in the mind of R. B. Williams, superintendent of the Scranton Division of the O&W, and close friend of J. J. Jermyn, Pittsburgh financier. The line Williams envisaged was to encounter the Lackawanna and the Delaware & Hudson in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., run between the two northward toward Scranton, cross the NYO&W at Hancock, curve through East Branch to, Margaretville, meet the U&D (now the New York Central) at Arkville, and parallel the D&H as far northeast as Delanson, N. Y., where it would cross the latter road and again run parallel with it to Schenectady. Freight rates on the big lines were high—too high for farmers and laborers in the east branch of the Delaware. The building of Williams' road originally called the Delaware & Eastern would mean coal pouring into the valley; lumber, blue stone, dairy products piled high on the flat cars and in the reefers moving out to , golden markets. Enthusiasm spread from Williams and Jermyn to F. F. Searing, New York banker who vacationed at Arkville and Andes. Searing promoted the capital that built as much of the D&N as ever materialized. The time was 1903-'06. Even before Searing's surveyors began to move along the Catskill paths, D&H officials bought stock in the Middleboro & Schoharie. Owned by the Vroman family, but operated as two independent branches, this eleven-mile road had a traffic agreement with the D&H, which, with the Pennsylvania, was planning a combination to reach Scranton. The fight was on. Newspapers in the little towns through the valley shouted black headlines: "Go to Albany for the hearing! Send a rousing delegation twenty-five strong!" "We were there, all right," Jim Welch remembered with a chuckle. "D&H's attorney asked if a line built by the D&H between Middleboro and Grand Gorge wouldn't serve the same purpose as the proposed road." "Right," Eckert joined in again. "Then Searing's attorney charged D&H with excessive rates; why, coal was $11 a ton, passenger rates five cents a mile or more. A big crowd of valley men had ganged in the hall. They began shouting at the commissioners, telling 'em D&H never carried any coal except what was produced in its own mines." He laughed. "They yelled and stamped on the floor, too, when it came to the question of grades; ours was less than the D&H's and our, route between Wilkes-Barre and Schenectady would be shorter." The maps were completed and work began on the road. In 1906, during the week of the incorporation of the D&E's subsidiaries, the Schenectady & Margaretville and the Hancock & East Branch, a local paper announced that track was already laid to Pepacton. Work was hustled to get to Margaretville in time for the county fair. The combined capital of the newly chartered roads was exactly $1,200,000; but Searing and Williams, the general manager, spent like the rail magnates they hoped to become. Creameries and depots sprang up at Arena, Shavertown, Pepacton, Downsville and Margaretville. Between 200 and 300 men, many of them Italians from Pittsburgh and Chi, were working on the Andes branch alone. The Lieutenant Governor, M. L. Bruce had a summer home at Andes, where it was expected vacationists would flock as soon as the first train rumbled over the new rails.

"We thought we were off to a flying start," Welch recalled. "Five locos, plus the other equipment, the new locomotive and repair shops here at Margaretville, forty-five miles of track from East Branch to Arkville, assorted creameries and depots along the line: we got ready to celebrate." A special car from New York brought President Searing, the officers and directors, up to Downsville on November 17th. Downsville sits snugly in a Swiss-like valley; surrounded by towering mountains and bumper-crop farms where fine horses and herds of dairy cattle graze. Searing's car halted at the depot, 125 feet below the creamery. A shouting crowd, distinguished, Ira Terry recalls a local newspaper reporting, by the Niagara-like beards of the men and the furred hoods of the women, swarmed the eight-foot platform all around the station house. The band paraded while R. B. Williams, who had driven the first spike at Arkville in September, 1905, drove the last spike of the completed road. "Nobody thought it was the last," Harry Miller said. PLANS, grandiose promises for the future, filled the frosty air as thick as hard-coal smoke. After the exhibition of typical vehicles, past and present, Searing stepped forward at the end of the observation car. When I first came to this valley," he orated, "people lugged merchandise from Walton twelve and fourteen miles over mountain's at an elevation of three thousand feet. I saw quarry stone carted by wagon from Shinhopple to East Branch. Now I see new buildings everywhere, banks opened, stone quarries, busy mills erected, timber tracts felled, lively bidding over property near Schenectady where the lines of the D&H and the Sehenectady & Margaretville Road will in the future run parallel." It was a great day. And the days that followed seemed like it to the young fellows who had pinned their dreams to the success of the road. Every day was excursion day. Barrels and oil rounds were set up inside the box and flat cars, planks laid across them, and men and women who had never seen a train before rode with cinders down their backs and hands batting at singed hair. Harry Eckert remembers one such trip with eight flat cars stretched out behind the two old coaches. The year 1906 saw 144,000 such passengers make the round trip from East Branch to Arkville and back. Freight traffic was heavy too. The stone factory at Arena shipped four cars of stone per week; lumber and dairy products went out by tons. The cauliflower industry, which had its earliest beginnings in the valley when Henry Van Benschoten, a Dutch farmer, planted a few rows of strange seed from the old countries, zoomed with three carloads per day moving toward city markets. Muir Trestle at Andes, 500 feet long, 45 feet high and containing 195,000 feet of lumber, was completed. At Prattville, work on the line to Schenectady rushed and slowed and rushed again. Founded by Zodac Pratt of tannery fame, Prattville stood 600 feet below towering cliffs, Schoharie Creek running southward through its fertile flats to lose itself in a bend of the Catskills. Railroad stakes went up to the southwest, amid the roar from Devasego and Manorkill Falls. The road was to cross the stream over a 150-foot trestle; looking up 100 feet, passengers would see water tumbling over the brink above, while 150 feet below the base of the falls foamed white.

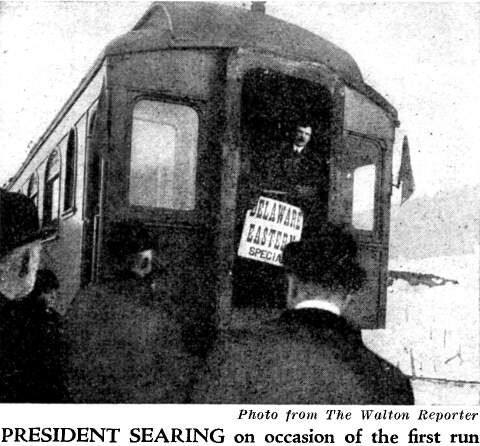

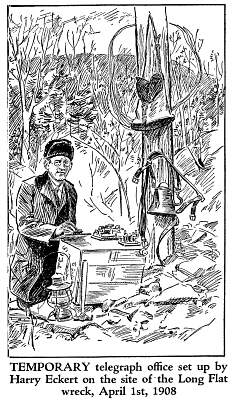

By February of 1908, Williams had asked for and received a leave of absence. The man who had planned the road and was responsible for most of its success so far, never returned to the struggling D&E until Searing was definitely out of it. Shortly after his return, he died. "That was a winter," Superintendent Welch reminisced. "Four judgments against us, aggregating $118,000; unpaid contractors howling bloody murder and the D&H chose the time to bring a motion to overturn the action of the old state board of Railway Commissions in granting our original charter. Workmen struck, supply houses refused credit on necessary tools and material; the road was behind in the payment of taxes." TOWNS between East Branch and Margaretville were lenient; but Hancock, a little beyond the eastern terminus of the road as it had been built and, therefore, less credulous in regard to the future, displayed considerable impatience at its failure to collect a $700 tax on the one-spot. The Hancock constable presented himself at the East Branch depot in the dead of night, and mounted guard over the cab with a gun. Next morning, when. Engineer Cowan appeared, he was forbidden to enter. The freight crew, with S. Fullerton conductor, awaited orders from the local office. They were told to withdraw, leaving the engine in charge of the constable. They did so, and a little later the delayed freight left East Branch behind No. 2, which had been rushed over from Margaretville. The day passed and the night, the constable keeping the fire burning and the steam up for his own sake. At noon on Sunday, Superintendent Wagonhorst with a fifteen-man crew, rushed down the track in No. 3, threw out a three-link, hitched it around the drawhead, and pulled. The constable threw the reverse lever in the one-spot. A tug-of-war ensued. The driving wheels slipped, sparks flew, the engines puffed and sputtered, and the men cursed. The slipping grew dangerous. Both crews then got out, put little pebbles on the rails to aid in giving traction, and returned to their respective engines. Number 3 backed up to No. 1, and going the full length of the chain, tried to pull the arrested engine her way. The chain broke, and the constable took his cab back to the starting point. Tug-of-war began again. One of the three-spot's crew, under cover of the escaping steam, crept around and loosened the relief valve of No. 1's cylinder, leaving her powerless. Old three put on full speed for Margaretville. Luckily, the constable's force jumped from No. 1, enabling the lead engine to settle down to a less dangerous pace.

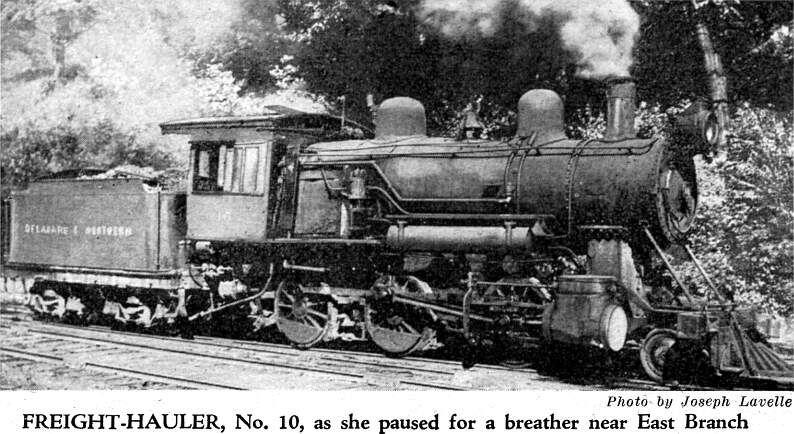

That night a special train to East Branch took all the D&E freight from the depot there. Saturday was the last day the Hancock tax warrant was in force and, therefore, another levy could not be made on Monday. Papers were made out for the arrest of the Hancock constable, charging him with assault with a deadly weapon. The Hancock chief of police retorted by arresting Wagenhorst on a charge of riot. Both proceedings were quietly dropped, but Harry Eckert remembers seeing Superintendent Wagenhorst sneak in over the covered bridge at Margaretville, head turned to look behind him. Things took an up-grade in September of 1909. Contracts, were let for construction at Grand Gorge. Boom days again. Camps for workmen lined the right-of-way. Final surveys rushed to keep out of the way of incoming carloads of men, powder, dynamite, steam shovels, dinky engines, dump cars, rails. Men and material poured into Grand Gorge, an inferno of congestion as gandy dancers strove frantically day and night to build sidetracks and storehouses. This time, the line was coming through! But ruin for Searing & Company was just in the offing. An attach brought by bond salesman F. P. Taglienna, on a claim of $85,000 arising out of commissions on the $3,500,000 worth of bonds Searing had employed him to sell in London, brought the end. Before January, 1910, the road was in receivership, with Andrew Moreland and Walter A. Trowbridge as receivers. The rest of that winter, the line struggled with flood, unprecedented snowfall, striking labor, more judgments, actions and restraining orders. HOPE rose again in 1911 when the road, just sold under foreclosure to William H. Seif, was reorganized as the Delaware & Northern. The general offices were moved to Margaretville, with James Welch appointed superintendent in full charge of the organization of all departments. The original engines, Nos. 1, 2 and 3 were scrapped, and new ones, all 4-4-0s, bought from the Chicago & Eastern Illinois. The Murray was retained, while. the George was kept on as No. 6. A four-wheel caboose also was added to the list of equipment at this time. Years later, in 1924 and 1929 respectively, the road was to acquire No. 7, a ten-wheeler, and No. 10, a Mogul, from the Emporia Manufacturing Co. But for the present, things were looking up mightily.

Between 1913 and 1917 a yearly average of 500 carloads of merchandise were unloaded in the valley. The Margaretville shop force reached the all-time high of twenty men with the purchase of two motor cars, a new coach and additional equipment. Between seven and ten men were employed in the office. Margaretville's annual county fair, complete with such attractions as hot-air balloon ascension, horse racing, cattle and canning exhibitions, brought thousands of passengers in from the surrounding villages and towns. Yet, in 1916, the line was forced to declare a profit and loss deficit of $26,097.

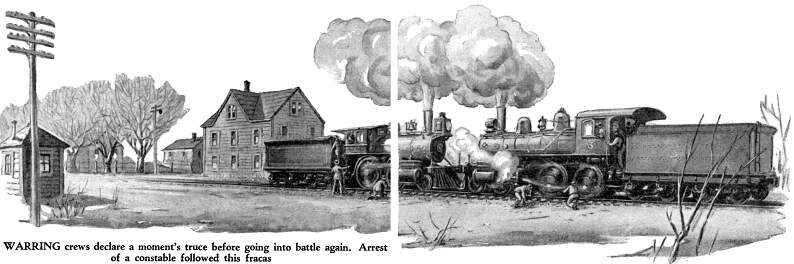

Villages along the line rallied to the support of the struggling road by reducing its taxes to $100 a mile. The citizens of Hancock collected among themselves the $1,500 which their township could not afford to rescind and paid it to Hancock in the road's name. "'People in the valley loved the D&N", Ira Terry remarked. "But love couldn't stave off the effects of postwar depression, automobile and truck competition plus chronic lack of working capital." The road went into its second receivership on March 16th, 1921. Against a motion to discontinue the road, brought by the D&H, the new receivers, Andrew Moreland and Jim Welch, proposed a $12,000 yearly reduction of expenses accompanied by a guarantee of operation for ten years to come. Employes accepted individual wage cuts to the required total; then, Judge Cooper ordered wages reduced 20 percent. A general walkout followed and continued during two days of unrest and dissension. On the third day business men along the route pledged themselves to make the cut good to the employes until August first, when receivers certificates' must be financed. "We shut off the Andes branch immediately," Welch continued. Other curtailments and economies, such as the purchase of a new gasoline combination passenger-mail-express car, kept the line going." Harry Miller laughed. "We sure thought that combination car was something! She took the place of a passenger train, made two round trips daily. I remember she had a fifteen-foot space for the railway post-office, fifteen feet for baggage express, and a passenger compartment with room for thirty passengers. The power plant was 250 horsepower gasoline engine, directly connected, like an automobile, to the wheels." ECKERT, who took her alone to East Branch and back a number of times, put in: "She had a six-inch bore and a seven-inch stroke, five speeds forward and in reverse. J. G. Brill of Philadelphia made her." "The old girl saved us around $30,000 a year," Superintendent Welch finished. "We bought her in 1926." "Too late for her to show up in Single Track," Miller grinned, referring to the Corinne Griffith movie filmed by Vitagraph on the D&N tracks in 1920. "Remember how the Public Service Safety inspector ragged us about Muir trestle on the Andes branch?" Ira Terry asked. "Well, Vitagraph wanted that trestle to look new for one of its shots. I don't recall exactly, somebody was to jump off the trestle, commit suicide there. Anyway, they sprayed the whole blame thing with water paint, clay colored. Two years later, the inspector looked at that bridge, jumped to the conclusion it actually was new, and gave us credit for having put up another trestle. Well we didn't open our mouths." Harry Eckert was laughing again. "Remember those dummies they used for the trestle jump? About four in all, I guess. They stored them in the toolhouse over at Andes, went off and forgot them. Everybody else forgot them too. Then Miller here sent one of the trackmen, an Italian, plenty superstitious, over for something one day. The scream that fellow let out when he pushed open the door and those dummies fell over him! He thought they were dead men, and so did all of Andes till some old-timer remembered and got up the nerve to investigate those 'murdered corpses'." The four rails chuckled together.

"Well," one of them said, "those were the days." Miss Griffith used to corral the roundhouse gang, take 'em all fishing. Used to wade out in hip boots and an old conductor's hat she'd picked up." He pointed up the tracks at the spot where Binikill divides from the Delaware by the width of a three-foot island. "Yep, just about there she used to stand, facing Binikill, the depot behind her. The D&N had its triumphs all right." In September of 1928, though, the Pittsburgh & Shamuth Coal Co., the Title Guarantee & Trust Co., and J. J. Jermyn, receiver, filed petition in Federal court to discontinue operations of the road.

"Then Sam Rosoff got interested," Harry Eckert took up the story. "Subway Sam. Born in Minsk, Russia, left it in the steerage, began life in New York as a newsboy, and now was just back from building the great Moscow subway system. He knew our history, he'd built the state improved highway through here ten years before. The most generous man I ever saw. In a way, he was another D&N triumph. He bought us on December 20th, complete with all sixty pieces of rolling stock, the depots, right-of-way, track; and took over on the 27th. That was 1928. Things began to hum." The Downsville News announced the sale with a remark that Rosoff had undoubtedly acquired the road "not so much for speculative purposes"—there was talk that he intended a $9,000,000,000 squeeze. play on the City of New York—"as to have the same as his own in hauling material for construction work on the dam to be built by the New York Board of Water Supply," and concluded with a careful aside to the effect that Rosoff undoubtedly had the contract for building the dam in his pocket before he invested in the half-defunct D&N. Much speculation as to the price paid for the road was voiced in all quarters. The Walton Reporter repeated the often suggested sum of $750,000. "Actually," Jim Welch remarked, "the price was $70,000. The bigger amount shows the speculative value, ownership of the road appeared to have. It did look as if Rosoff were gambling on a sure thing. The reservoir was slated, the dam had to come; a man who owned the railroad could underbid every other contractor. Nobody could guess that war was coming, with shortage of materials and practically complete stoppage of such projects." The New York Times gave Rosoff's price as ten cents on the dollar. The fact that he was sole owner, the article continued in a tone of enmity obviated the approval of the Public Service Commission. Two days, later the World intimated that an investigation was due; Governor Roosevelt (now the President) should inquire minutely into the question "whether the state's interest in the development of the Delaware water resources would be jeopardized in any way by Rosoff's purchase."

Then, suavely, a New York paper reported the Interstate Commerce Commission as "against the policy of granting extensions, that will increase competition among railroads," with a pointed addition to the effect that "there are few places in Pennsylvania, where the Delaware & Northern might extend without touching other roads." Before the Public Service Commission, which heard him without

opposition from the City of New York, Rosoff announced his willingness

to raise the D&N track to a point higher along the mountain

route if and when the city should require the entire right-of-way,

or the estimated two-thirds of it, for the site of the city's

reservoir. He added that he was willing to sell at the city's

own, price. ONE of the highlights of those days was the installation of a special train for the school children of the valley. "If I can help these children get an education, I'll do

it even if I have to carry them for nothing," the former

newsboy said. "We were in the limelight those years, too," Supt. Welch commented. "New York newspapers featured us every time Rosoff's new motor bus left the track. We never had even the average number of wrecks, but they made it seem like we couldn't make a run without a collision or an accident. The motorbus hit a New York Central locomotive in a headon collision at Arkville. Damages around $8,000. In 1934, the gasoline bus left the rails above Arena. They played that up big. Carried pictures of the wreck—'Crash Injures Children.' About ten of the passengers were slightly hurt, but the newspapers were gunning for Rosoff. He looked too big to a lot of people." "We sort of rolled along in those years," Eckert continued the story. "Used to halt whenever we took the notion. Trainmen like to chat along the way. Remember once, just below Downsville, No. 3 was to switch below the creamery. Part of us switched her; the rest got off to pull a farmer's truck out of the mud. That was D&N service. Used to stop anywhere between points if we had something to deliver; didn't matter, one package was enough. Most of the young fellows were on their way out—" "I got out," Ira Terry explained. "All the younger men did. Hated to, but we had to live. The gasoline car was the only thing kept the railroad going those last years." "Sure," Miller nodded. "I went into insurance myself. Couldn't somehow, change over from the D&N. The payroll had jumped from 325 men around $45,000 a month, to next to nothing. Towns around here began to look like ghost towns; that is, as far as a railroader was concerned. No use in hanging on, though you wanted to," he admitted.

"And that was really the end," Eckert recalled. "Negotiations dragged on. Sometimes it seemed like they dragged on forever. You'd got sick of it by that time. Then, October 16th, 1942) they tacked the notice of abandonment on the depot doors from Arkville to East Branch. That was it. Done." The four old-timers turned from the deserted sidings, the rotted old coaches and flats and the closed depot where the first steam shovel was sunk in 1904. Harry Miller laughed suddenly. "We went out in a blaze of glory, sort of," he explained. "Got mixed up with the FBI, no less. Couple of kids around seventeen heaved a pile of ties on the tracks at the bridge across Tremperskill one Friday night in April. Just happened we didn't run a train until Monday—one of our off weeks," he grinned. "Section foreman found the ties Sunday morning. Somebody got excited and reported the whole business to the U.S. Commissioner at Binghamton. Well, they put those kids under $1,000 bond each and announced the D&N was used considerably for shipment of materials to defense plants.' Miller cocked his head at Jim Welch. "Know what those shipments were, Super?" Welch grinned back at him. "Must have been that blue stone went down to Washington to build one of those new Government buildings."'

Harry Eckert looked back. "Forty thousand tons of scrap metal," he said. "Old coaches, locos, everything worth $50,000. They say she'll make four hundred medium tanks." He was looking at the end of a road, at the end of a dream. He glanced up. Around the curve below the old switch signals came the D&N handcar. She was stepping along like a redball freight when we first caught sight of her. The "engineer," somewhat bigger than the four little shavers who sat atop, stumbled over a rotted tie. The car lurched, righted herself, and went careening past us into the Margaretville station. Harry Eckert caught his breath, laughed. "That's it, brother—a swell little pike, and still a going concern, by dad!"

Catskill Legacies | Stories Page | Contents Page

This page originally appeared on Thomas Ehrenreich's Railroad Extra Website

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

On completion

of the road between East Branch and Arkville, the rolling stock

consisted of two passenger engines, the Searing and the Williams, both bought in 1905; three freight locomotives,,

the Fairchild, the George and the Murray,bought

in 1906 and named in honor of three of the directors; two coaches,

several box and flat cars, one of which sported a hand derrick,

and a single caboose, an eight wheeler. The passenger locomotives

both 4-4-0s, were numbered 1 and 2 a few years later, when the Fairchild became the three-spot. Engines George and Murray, also 4-4-0s, took their place in line as 4 and

5. All the cabs including the mogul, Fairchild, were originally

owned by the Lackawanna.

On completion

of the road between East Branch and Arkville, the rolling stock

consisted of two passenger engines, the Searing and the Williams, both bought in 1905; three freight locomotives,,

the Fairchild, the George and the Murray,bought

in 1906 and named in honor of three of the directors; two coaches,

several box and flat cars, one of which sported a hand derrick,

and a single caboose, an eight wheeler. The passenger locomotives

both 4-4-0s, were numbered 1 and 2 a few years later, when the Fairchild became the three-spot. Engines George and Murray, also 4-4-0s, took their place in line as 4 and

5. All the cabs including the mogul, Fairchild, were originally

owned by the Lackawanna. Meanwhile,

trouble brewed. Searing and Williams were at loggerheads. A telegram

addressed to Williams and received at Andes in 1907, reads: ''You

fellows make me sick. No team work here. F. F. Searing."

The story, Jim Welch explained, was not, as Searing intimated,

one of negligence on the part of Williams and the local officials,

but one of unpaid crews and consequent delays on all sides.

Meanwhile,

trouble brewed. Searing and Williams were at loggerheads. A telegram

addressed to Williams and received at Andes in 1907, reads: ''You

fellows make me sick. No team work here. F. F. Searing."

The story, Jim Welch explained, was not, as Searing intimated,

one of negligence on the part of Williams and the local officials,

but one of unpaid crews and consequent delays on all sides.

Since 1907

New York city surveyors had swung chains through the valley in

search of a proper site for a new water reservoir. The failing

road saw in this a hope for the future. D&N officials met

with representatives from the various towns, to discuss an extension

from Andes to Bovina, with a view to building a branch line from

Grand Gorge to Prattville over which to haul the immense supplies

that would be needed for the City's dam. By 1915 the town of Bovina,

still refused the necessary guarantee, and the plan had to be

dropped. The reported income loss, due to operating under Federal

control from 1918 to 1920, was $50,898. With a $29,392 deficit

staring them in the face, D&N officials petitioned the Public

Service Commission for permission to increase its passenger rate

from 3.6 cents a mile to 5 cents.

Since 1907

New York city surveyors had swung chains through the valley in

search of a proper site for a new water reservoir. The failing

road saw in this a hope for the future. D&N officials met

with representatives from the various towns, to discuss an extension

from Andes to Bovina, with a view to building a branch line from

Grand Gorge to Prattville over which to haul the immense supplies

that would be needed for the City's dam. By 1915 the town of Bovina,

still refused the necessary guarantee, and the plan had to be

dropped. The reported income loss, due to operating under Federal

control from 1918 to 1920, was $50,898. With a $29,392 deficit

staring them in the face, D&N officials petitioned the Public

Service Commission for permission to increase its passenger rate

from 3.6 cents a mile to 5 cents.

"We were

at the end of every chance," Jim Welch recalled. "Busses,

trucks, cars, the whole new setup of the late Twenties and early

Thirties ruined us. Increased use of cement stopped paving and

flagstone shipments, the mountain sides were stripped of timber,

no lumber was going out; even the chemical plants closed because

the wood supply was exhausted. There wasn't enough traffic to

pay for running one train per day. The three months that followed

that petition, well, we had to sit here and see the line rusting

clean out from under us."

"We were

at the end of every chance," Jim Welch recalled. "Busses,

trucks, cars, the whole new setup of the late Twenties and early

Thirties ruined us. Increased use of cement stopped paving and

flagstone shipments, the mountain sides were stripped of timber,

no lumber was going out; even the chemical plants closed because

the wood supply was exhausted. There wasn't enough traffic to

pay for running one train per day. The three months that followed

that petition, well, we had to sit here and see the line rusting

clean out from under us." "Up here,"

Eckert explained, "we didn't know what was happening. Why,

we were getting ready to extend the line. We were going to finish

that old Schenectady-Margaretville route up in style; go down

to Wilkes-Barre, bring out the anthracite and follow up straight

to Schenectady. The old dream, it was coming true at last, and

here we were, fellows who'd stuck to the road through thick and

thin, through everything: we believed it, we thought it could

happen."

"Up here,"

Eckert explained, "we didn't know what was happening. Why,

we were getting ready to extend the line. We were going to finish

that old Schenectady-Margaretville route up in style; go down

to Wilkes-Barre, bring out the anthracite and follow up straight

to Schenectady. The old dream, it was coming true at last, and

here we were, fellows who'd stuck to the road through thick and

thin, through everything: we believed it, we thought it could

happen." Like a bolt from

the blue came the announcement that New York City had moved to

block the reorganization plans. The Public Service Commission

denied the D&N a permit on the same day that eighteen carloads

of the new 85-pound rails arrived in Andes, Middletown and Colchester.

The little road seemed about to collapse again. Not until December

of that year was the reorganization finally approved by the Interstate

Commerce Commission. By that time, though, the depression years

had arrived. The freight cars behind old No. 10 swayed empty around

the Catskill curves.

Like a bolt from

the blue came the announcement that New York City had moved to

block the reorganization plans. The Public Service Commission

denied the D&N a permit on the same day that eighteen carloads

of the new 85-pound rails arrived in Andes, Middletown and Colchester.

The little road seemed about to collapse again. Not until December

of that year was the reorganization finally approved by the Interstate

Commerce Commission. By that time, though, the depression years

had arrived. The freight cars behind old No. 10 swayed empty around

the Catskill curves. In 1939 Subway

Sam sold the D&N to the City of New York for an even $200,000.

He had sunk $60,000 a year in the line from the date he bought

it up to the date he sold. Traffic had dwindled to almost nothing;

the right-of-way was needed for, the reservoir site; and it was

impracticable to raise the tracks higher on the mountain sides,

as had been planned earlier.

In 1939 Subway

Sam sold the D&N to the City of New York for an even $200,000.

He had sunk $60,000 a year in the line from the date he bought

it up to the date he sold. Traffic had dwindled to almost nothing;

the right-of-way was needed for, the reservoir site; and it was

impracticable to raise the tracks higher on the mountain sides,

as had been planned earlier. The valley

is still prosperous, they explained. Farm produce, blue stone,

some lumber go by truck to meet the NYC at Arkville, and vacationists

come in via the NYO&W at Kingston.

The valley

is still prosperous, they explained. Farm produce, blue stone,

some lumber go by truck to meet the NYC at Arkville, and vacationists

come in via the NYO&W at Kingston.