|

A LOCOMOTIVE ENGINEERESS

By Bella Lee Dunkinson

Frank Leslie’s POPULAR

MONTHLY — June, 1888

IN

glancing over some discarded jewels of earlier years the other

day, the memory of a daring girlish exploit in the Cumberland

Mountains of Tennessee became vivid, designed to be perpetuated

by the little coral necklace, yet cherished, given to me by the

miners of that region for what they were pleased to consider as

a timely and providential exhibition of presence of mind, while

in reality it was only one of those strange freaks occurring in

the lives of us all, and which may be ascribed to the accidental

or miraculous. IN

glancing over some discarded jewels of earlier years the other

day, the memory of a daring girlish exploit in the Cumberland

Mountains of Tennessee became vivid, designed to be perpetuated

by the little coral necklace, yet cherished, given to me by the

miners of that region for what they were pleased to consider as

a timely and providential exhibition of presence of mind, while

in reality it was only one of those strange freaks occurring in

the lives of us all, and which may be ascribed to the accidental

or miraculous.

The act commemorated by this souvenir

of those rough and hardy men of toil was in my being called upon

to take command of a locomotive drawing a heavy train up the circuitous

slopes of that range, under circumstances, as I view them now,

quite interesting and startling. The facts were these: At the

time when sectional feeling ran high in the Border States, just

before the outbreak of the Civil War, many Northern families went

to Western Tennessee to assist in opening the mining industries

of that rich region, which promised very large returns for those

who embarked effort and capital. When I say many, I mean in proportion

to the sparse population scattered over the mountain slopes. Those

who went there were generally venturesome spirits, fond of the

semi-wild life "way up" in that summit world; but they

were not near enough together to found any intersocial relations,

for activity, ceaseless by day and by night, reigned in each little

mining hamlet, and the young of both sexes were as enthusiastic

in the solution of all physical problems in the subterranean galleries

as the wise heads and sturdy arms directing the operations for

gain. What, therefore, were the opportunities of a young girl

gifted with a light heart and a sound digestion, in the way of

everyday enjoyment? Sunday-schools, crochet parties, roistering

hops, tea and slander combined, musings over the fashionable poet

of the day—these and many other forms of distraction for

the average village maid were impossible. Even had social intercourse

been possible with the native inhabitants—barred, of course,

by the hostility prevailing against all those of Northern birth

and proclivities—there was little to tempt the girl fond

of her piano and the lighter accomplishments taught in our Northern

seminaries. Hence I fell to a wild, outdoor life, following all

the sports there prevailing, and mingling daily with the miners,

talking their lingo, watching them in their daily excavations,

and a personal friend and chum of every one of them. Although,

perhaps, it may seem that this kind of existence was not exactly

in keeping with the strict lines of behavior laid down for the

sex in general, yet I am certain that those years of boundless

freedom and outdoor life, high and low, not only led to a robust

constitution, of great importance in meeting the pestiferous airs

of other climes, but were far more valuable to me than any experiences

in the polished circles subsequently had in different countries

of the world. Dolls, toys, baby paraphernalia, girlish amusements

of all sorts, I chose to discard, and, true, to the narrative,

I had an ambition to be a man —to be like one of those heroines

so powerfully drawn by "Ouida." So it happened that

among other habits which I formed was to ride almost daily on

the locomotives which hauled the trains up and down the mountain-sides

over heavy grades and around sharp curves, and in this way I became

a favorite, and not unfrequently a useful, assistant of the engine-drivers.

And often it was, too, that I handled the, machinery, proudly

directing the iron horse on its upward or downward flight between

the railway termini. This roadbed ran from Cowan’s Station

in the valley, up a distance of twenty-five miles, to the very,

mouth of the mines.

On one of these trips up to the deep

shaft which formed the entrance to the mines occurred my most

dramatic experience in those regions, and which came near, being

a tragedy not often paralleled in modern catastrophe or romance.

A train laden with merchandise and lumber

for the miners’ cabins started on its upward trip from Cowan’s

Station, one hot evening in August, just as the sun was falling

below the timber of the valleys. As I was to accompany the engineer,

John Hardiman, on the locomotive the regular fireman or stoker

was permitted to remain at his home at the foot of the mountains,

although it was contrary to the rules of the company. We steamed

up the grade with seven cars, a caboose, a single brakeman, and

our unusually heavy load, and the natural duration of the run

was an hour and ten minutes. Presently John said to me: "I'm

afraid, Belle, there’s not enough steam in her to carry her

through. We’ve a heavy load, sure, and a big storm gatherin’.

So if anything happens, you stand by her, and I'll look out for

the track."

We sped on, not at any very encouraging

pace, as both of us could perceive, and John began to pile on

the coal to make more steam, while be intrusted me with the command

of the machinery. All of a sudden there came rapid and vivid flashes

of lightning, followed by terrific peals of thunder, and then

a down-pour of rain such as I had never before witnessed in those

mountains.

Fearing now that we were on a journey

sufficiently perilous, I knew enough to estimate that the added

danger was of no small consequence in driving the engine up steep

grades, around sharp curves, by heavily encumbered sidings, through

a thick, gloomy forest whose overhanging boughs made all progress

through an almost literal tunnel of dripping foliage. Nor were

we long in discovering it was a solemn fact that it was only a

miracle that would prevent us from becoming stationary on the

rails, even if the solitary brakeman at the rear could prevent

us from losing command of the train, in which case it would start

on the inevitable backward and downward journey which might land

us in some deep gulch by jumping the roadbed in all of the horrors

of that terrible stormy night. And among the agonizing features

of the situation was the fact that we were soon unable to tell

whether we were making any progress up the grade or not. The thunder

and pelting storm came in such choral crashes that we were uncertain

whether the wheels beneath us were simply revolving on their axles,

or whether we were in reality going up, for the leafage overhead

was so dense that the lightning was no beacon. But, suddenly,

there was an open space skyward, and the brilliant flashes above

us made John exclaim, "Great God! we are, standing still!"

It was at this moment that the cool-headed

engineer signaled the brakeman to down brakes, and, giving me

encouragement and admonition, jumped from the engine to sand the

track.

As may be imagined, I never felt a greater

responsibility in my life, and, besides, there was something in

the cool confidence with which he trusted in my nerve and discretion,

that I felt it was the proudest moment of my varied existence

in the Cumberland Mountains.

No sooner had he dismounted than I knew

by the flashes in the now perceptible sky that we were moving

down the incline, and that the brakes were powerless to stay the

slow movement backward around the curve. It was, therefore, now

or never to turn on all steam, although the engineer, could not

again ascend, to his station. It was a literal case of make or

break, of life or fearful death.

We must at this moment—the vital

one of the whole ride—use all the steam-power in that boiler

or soon be a wreck down a fearful plunge among the crags and treetops

and watercourses, thousands of feet below. The train was then,

probably, some eight miles from Cowan’s Station, and I at

once let the engine have all steam, for the fire on the grate

had come to a white heat, and, if sufficient water had been vaporized,

all would be well. There was a momentary lull in the storm, and

I could feel and perceive that the monster locomotive was laboring

to save the train, the big traction-wheels flying around with

frightful rapidity.

Soon I knew they had caught a purchase

on the rails. It was the sand that Hardiman had scattered there

to save us from destruction. We began to move, with loud and stertorous

breathing from the nostrils of the huge machine—so often

heard when the locomotive is in powerful exertion to draw a heavy

load—and there I stood, all excitement, as it were, at the

bridle of the engine, bound on a dangerous flight through the

dark mountain forest, uncertain as to where the landing might

yet be, for the curves were abrupt, the ascent steep, and I must

be content with the coal in the fire-box, and cautious in speeding

the train over the shaky trestles and uneven road-bed. But on

went the winding file of wagons with the merchandise for the miners,

and I in supreme command. The principal dangers, perhaps, after

I obtained headway, were the switches and sidings, because in

those days, in Western Tennessee, railroading was a science still

in its infancy.

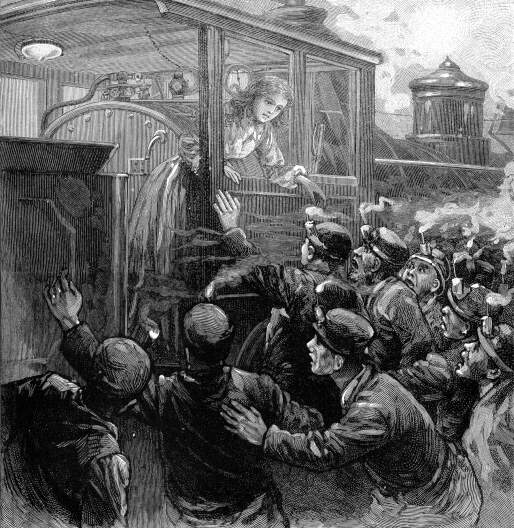

But on went the train without accident

or serious incident until it rolled up within a few hundred yards

of the mouth of the shaft, where there were many laden cars standing

on the sidings. But there I found more than one hundred of the

miners with their nightlamps flashing in the dark, apprised by

telegraph from below that disaster might occur, and, as I brought

my command to a stand at the very entrance of the shaft, a rousing

cheer was intermingled with the artillery-like thunder; not for

me, but for Hardiman and the safety of their household effects.

But when these honest, brawny fellows gathered about the engine

to invite John Hardiman to a bumper, and they found it was not

he, but their "Belle of the Mines and Mountains," their

enthusiasm was great indeed. And if there be any egotism in relating

this incident happening in those young years of my girlhood, I

am willing to suffer the accusation for the thrilling memories

of that experience, as, I write it for the public eye.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|