|

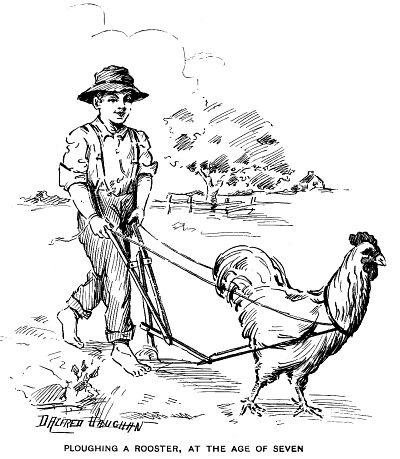

CHAPTER I—EARLY DAYS; PLOUGHING THE ROOSTER

I WAS born on Christmas morning in 1838, on an island in the

Chattahoochee River, Harris County, Georgia, but when I was two

years old the family moved from there to Troup County, where my

father was engaged in selling whiskey. This place was called Cleveland's

Cross-Roads, and there, at the age of six years, I got drunk for

the first and last time in my life. I remember falling into a

hole that was full of water, but managed to scramble out.

My father professed religion while living here, sold out his

whiskey business, and moved to Louisiana. This was in 1844.

In those days there was a man in nearly every community who

was celebrated for his fighting qualities. The settlement in which

we lived had its "bully," and the man, Jim Hunter by

name, knowing that my father had a reputation as a fighter, disputed

the championship, and boasted that he would whip him before he

left. The fight started, and Father's hat blew off. I picked it

up, then stood by and watched the fight. Our side beat. The "County

Bully" was so badly used up that he cried for mercy and begged

the people there to "take him off." I handed my father

his hat, shouting gleefully, "You are the best man in the

county, Pa; you licked Jim Hunter."

A few days later we started on our journey to Louisiana, travelling

through the country. Our teams consisted of a four-mule wagon

and a one-horse carriage. We camped when night came, and slept

in tents, and young as I was, I assisted with the tents, and anything

else there was to do. Our fare consisted of meat, bread, cheese,

crackers, and coffee. I fell out with cheese then, and for years

wouldn't have anything to do with it.

When we arrived at Wetumpka I was very much interested in seeing

the guards, with their guns on their shoulders, walking the state

penitentiary walls to guard the prisoners.

We travelled very comfortably until we struck the corduroy

roads in Mississippi, when the jolting was so rough that I much

preferred walking to riding. We saw an Indian camp one day. There

were quite a number of these dusky people, and they seemed to

take as much interest in us as we did in them. There was one old

fellow under the influence of liquor, and he followed us for some

distance, being accompanied by some of the rest of the party.

They kept up a kind of song with the words, "Where did you

come from, daddle-daddle-dah?" proving that they had acquired

some knowledge of English. We kept travelling until we came to

a house, where we got permission to take our beds inside, for

safety. Father and one of the negro men kept watch all night,

but we were not troubled by the Indians.

When we were on the road, I brought up the rear of our procession

carrying a gun on my shoulder, and thought myself an important

member of the party. We passed Jackson, Mississippi, then on to

Vicksburg. After crossing the big, black river, we came to a railroad

called the Vicksburg and Jackson, where I saw my first locomotive.

That was a wonderful sight to me; but little did I think then

that most of my life was to be spent running one. Almost twenty

years later I passed, as an engineer, over that same Vicksburg

and Jackson R. R., and coming to the place where as a small, wondering

boy, I saw my first locomotive, recognized it immediately.

Upon taking our departure, we crossed the river in a steamboat,

and found the ground very muddy when we started on our line of

march, while the marks on the trees showed a rise of eight or

ten feet.

We passed three other large streams of water (at least they

seemed large to me), known as Bayou Beth, Bayou Mason, and Bayou

Bartholomew.

Travelling nearly across the State of Louisiana, we settled

at Jackson Parish, nine miles from Verona, which place was about

thirty miles from the state line of Texas.

Our home was situated on a high hill, and consisted of one

large room, twenty-two by eighteen feet, built of hewn logs, with

puncheon floor. The kitchen was less pretentious; about twelve

by sixteen feet, and, as was the custom in those days, some distance

from the main house. When my mother would be preparing supper,

I often saw wolves on an adjacent hill, being attracted there

by the smell of the cooking food. They were so numerous that they

would come in herds, like sheep, and grew so bold that at times

they would go in the yard after chickens when the dogs were away

on a hunt.

There was no clearing when we first settled here, and the woods

were thick. We raised corn, cotton, potatoes, peas, beans, water-melons,

and pumpkins, the latter in great abundance, some of them being

fully three feet long. Besides supplying the family, we had all

that the horses and hogs could eat. One horse, Fox by name, ate

so many, that his hair grew to be about three inches long.

Coons were plentiful in that locality, especially in "roasting

ear" time, and I would often start on a hunt with the dogs

about four o'clock in the morning. The hounds would trail them,

but the large bulldog always kept near me. The woods were alive

with various kinds of wild animals, with snakes everywhere, so

Bull seemed to think that he ought to stay near and protect me.

The following spring, after the land was cleared, and the plowing

done, I saw how nice it looked, and decided I would have a "new

ground" myself. So, one Sunday while my mother was away,

I made a plow-stock, then looked around to see what I would do

for a horse. I spied a large rooster that Mother prized very highly,

caught him, made a harness to fit, and put him to plowing. I finished

my work, but just as I got through, the rooster refused to go.

I unhitched him, but it was too much for him; he died that day.

I thought I would get a switching, but when I took Mother to see

my "new ground," she looked it over, and let me off

with a reprimand.

We lived at that place two years, and each member of the family

averaged two or three chills a week; then Father decided to move

back to Georgia where we could get good water, as our drinking

water here was carried from a spring about a quarter of a mile

from the house. When two buckets were filled, the spring was nearly

dry, and I frequently carried a handful of salt to throw into

the spring to improve the taste of the water.

Before leaving this subject, I

want to say something about the Louisiana trees. They consisted

chiefly of different varieties of oak, and were so large that

when cutting them down for rails, there would be from four to

five ten-foot cuts before getting to the limbs. The cotton in

this section grew to immense size also. On one occasion, I climbed

a stalk for a distance of two feet, and it didn't even bend with

my weight. Before leaving this subject, I

want to say something about the Louisiana trees. They consisted

chiefly of different varieties of oak, and were so large that

when cutting them down for rails, there would be from four to

five ten-foot cuts before getting to the limbs. The cotton in

this section grew to immense size also. On one occasion, I climbed

a stalk for a distance of two feet, and it didn't even bend with

my weight.

We started back to Georgia in 1847, going by way of Monroe,

a place on the Washita River, thence to Vicksburg, on through

Mississippi swamps, and over corduroy roads until we struck the

higher lands.

At different places along the route we saw negroes driving

from four to eight yoke of oxen. I was much interested in that

sight, as I had never seen so many of the "horned horses"

in one team before, and wondered how they could be driven without

lines.

I did not enjoy the return trip as much as I did going to Louisiana,

for the chills attacked me, and every day or two interfered with

my comfort and enjoyment.

After travelling four weeks, we arrived at Troup County, Georgia,

where, having good water to drink, we soon ceased to have chills.

My father first rented a place, and I went to work on the farm.

Our nearest neighbor was about a fourth of a mile away. The man's

name was Jack Burk, and his wife bore the "old-timey"

name of Huldah. Almost any time in the day we could hear Huldah

calling or scolding "Jackey Honey." He, however, didn't

seem to have much concern about it, but would go along, singing

hymn tunes.

The next year we moved east of there and settled near a cotton-mill

situated on Flat Shoal Creek. Father bought this place, and we

remained there three years farming.

I was eleven years old at this time, and it was the beginning

of my limited education, as I went to school two months during

the last year's stay, after the crop was laid by.

Our next move was to another farm about six miles away, and

this was the best and most comfortable home we ever had.

There was a mill on the place run by water, and, besides getting

our own corn ground, we supplied the farmers in the settlement,—taking

toll for the grinding.

The small creek on which the mill was situated, being only

a half-mile away, was selected by my brothers and myself as a

bathing place; and we would go there on Sundays.

My mother didn't approve of our going in the creek, and in

order to keep us from it, she left the buttons off our collars

and wristbands, and when we got on our clothes, would take needle

and thread and tack them together. The thread was always the same

kind,—that which Mother spun and twisted,—generally

blue and white. While the other boys were being "tacked,"

I would slip around, secure a needle, unwind some thread from

the chip, and be prepared for emergencies.

When we came out of the creek I would bring out my needle and

thread, "tack" the boys all around, then one would "tack"

me, and Mother would be none the wiser. Sometimes her suspicions

would be aroused, and she would put her hand on a boy's head,

and say, "Well, your hair looks damp, but the tacks are all

right."

We enjoyed our weekly swims for quite a while, until, one day

when I was still in the creek, and my clothes were hanging on

the bushes, a cow came along and went to chewing on my garments.

Mother made our clothes—cloth, garments, and all—and

my Sunday suit was extra nice. It was made all in one piece. A

kind of body sewed, on the pants, and two little coat-tails, swallow

fashion, sewed on behind, at the waist.

That destructive cow had chewed one of the tails off my suit!

Of course Mother wanted to know how it happened that my Sunday

clothes were in such a plight, so I had to own up. The collars

and sleeves were all tacked, as usual, so Mother said, it was

"no use to try to get ahead of boys," and sewed on buttons.

I decided that I would get even with that cow for getting me

into trouble, so the next Sunday we rounded up all the cows we

could find, and made them jump off a bluff about fifteen feet

high into the water. I thought I had satisfaction then, and went

home contented.

After the tail was sewed on my garment, and buttons on my shirt,

I decided, as I was in such fine trim, I would go to Sunday-school.

I yet remember, as distinctly as if it were yesterday, the lesson

that Sunday. It was about John the Baptist.

On my way home from Sunday-school, I stopped and took dinner

with one of the boys. Something I ate for dinner disagreed with

me and made me sick. I connected my trouble with Sunday-school,

and that was my first and last appearance. I was thirteen years

old then, and have never been to a Sunday-school since.

Shortly after this, Father decided to send me to school again,

and I attended, this time, nearly four months.

The teacher was a refined lady, Mrs. Whitby, by name. She sometimes

took a small boy to school with her. That small boy grew to be

a large boy, and is now one of Selma's foremost dentists.

A family of four girls attended this school who were always

making a disturbance with the other pupils. They started a quarrel

with my sister, who was a little more than two years my senior,

and were about to fight her, all four consolidated, when I stepped

up and told Florence to stand back, that I would do her fighting.

I knocked the girls right and left, and came out victorious. They

reported me to the teacher, and added that I had used bad language.

In my wrath I had made use of a name of which I did not then know

the meaning and that was sadly to their discredit. When Mrs. Whitby

asked me what the word meant; I replied, that "it was people

who were always talking about somebody."

My explanation satisfied the teacher, but the Bass family would

not accept it. A big brother of the girls made his threats that

he was going to whip me; so I armed myself with a large knife

and made ready—but he never molested me.

Shortly after this I stopped school and went back to work on

the farm.

Father had made a good deal of money at this place, so he bought

six negroes, then moved to North Georgia where he settled in Cass

County, five miles from Cassville, remaining there one year. At

the end of that time he bought a farm one mile from Cassville.

On this place was a gin-house with a thresher attached, and

I ginned all the cotton and threshed all the wheat. During our

second year there, my father sent me to school for three months,

after which time he said he needed me on the farm. I made all

the plow-stocks, and all the baskets that we used in picking cotton,

besides assisting with the plowing. Between times I hauled wood

to town and to the railroad, having to rise at four o'clock, "roust"

the negroes out, and get to work.

The third year I was again started to school,—a college

this time—that had just been completed. I attended here two

or three months, but, getting into trouble then, my school-days

ended. The trouble came about in this way. The bell had been rung

out of school hours, and I was accused of doing it. Upon denying

it, my word was not taken, and I was called before the faculty

and informed that I was not to speak to any one for four days,

as punishment. As I walked out, one of the professors, Mr. Roberts,

said to the boys: "All of you get away from Thomas, he is

not allowed to speak to any of you for four days." I was

quite indignant at this unjust treatment, and my temper blazed.

I told the gentleman that "my tongue was made for talking,

and that neither he nor the whole faculty could keep me from using

it." He called the other three teachers and they rushed at

me. Backing up in a corner, I drew out my "Arkansas toothpick,"

the blade of which was five inches long, and told them to "come

and get me." They stood looking at me for a while, then left,

one at a time. I then walked into the schoolroom, got my books,—three

in number,—said goodbye to my teacher and went home, taking

up my farm work again.

About a week after I left the college, the principal told Father

that they had discovered I was innocent of the charge against

me, and said he wanted me to go back. I refused to return, remarking

that they might treat me that way again. I was then sixteen years

old, and my work consisted mainly of driving a four-mule team.

Father decided that he would "swap" his mules for

horses, which was not a wise move, as we discovered that the horses

would not pull as well as the mules.

One day as I started off with a load of corn to take to the

mill, the horses stalled on a hill, not far from home, and refused

to pull. I sent a message to my father, telling him that I couldn't

get the team up the hill, and asking what I should do. He came

to investigate; and, upon arriving, told me that I was not fit

to drive a team. My temper rose, and I agreed with him. Then,

telling him that I would never do any driving for him again, I

gathered together my belongings and left home that day.

Table of Contents

| Next Chapter | Contents

Page

|