The Minnesota Pineries The Minnesota Pineries

Harper's New Monthly Magazine

—March, 1868

WHEN a Minneapolis or St. Anthony lumberman contemplates a

business visit to the pine regions of Northern Minnesota he expresses

his intention by saying that he is "going up river."

The appropriateness of such language is apparent enough when we

learn that the portions of country referred to lie on the Upper

Mississippi and its tributaries. One of the most important of

these tributaries, especially in connection with the pineries

of which we speak, is Rum River; and thus, when one of the lords

of the Minneapolis lumber-mills invited me, in the early part

of March, 1867, to go with him "up river," I knew at

once that it signified a journey to the lumber-camps on one of

the above streams, a hundred miles or more from home, and well

into those forests which stretch their unbroken solitudes far

toward the shores of Hudson's Bay. I was more than willing to

accept the invitation, for I had long cherished a desire to see

those famous forests, to go over the old Indian hunting-grounds,

and, not the least of all, to snuff the pure native odor of freshly-cut

pine logs.

This time "up river" meant up Rum River, a stream

which joins the Mississippi on the east, at Anoka, eighteen miles

above St. Anthony Falls. How or when it received its anti-temperance

name is not known, at least to the writer, but, like most of certain

beverages common nowadays, it contains more water than rum—and

the more water the better in both cases. It is a singular coincidence

that either the river itself or one of its principal branches

has its source in Sugar Lake.

Although the place of our destination lay near the sources

of Rum River, we found it more convenient to go by rail some twelve

miles above the junction of this river with the Mississippi to

Elk River, and thence across by a shorter route. Our friend had

taken the precaution to send up on the previous day his own sleigh

and horses, which were nearly ready for us as we alighted, about

twelve o'clock, from the cars. Taking a hurried dinner at the

very unpretentious Elk River Hotel, we prepared for a trip of

twenty miles or more over the prairie, and in an atmosphere that

was driving the mercury below zero. We toasted the bottoms of

our boots, strapped on our cloth overshoes, slipped into our beaver

coats (my friend added a wolf-robe), wrapped our shoulders with

shawls, pulled our caps down over our ears, then, jumping into

the sleigh, and covering our limbs with a well-lined buffalo-skin,

started off; feeling as though we could safely defy the blasts

of Spitzbergen. George and Kate, our noble steeds, dashed on at

a splendid rate. The latter animal was once a rebel, or probably

was, as she was owned by one. She was captured by a distinguished

Federal officer, near the close of the late war, and brought North;

instead of returning to champ the Southern bit again she remained

to obey the reconstructive reins of her Minneapolis owner, who

provides her with plenty of loyal hay and oats, and who is as

proud of her as though she had her birth in sight of Bunker Hill.

She trotted so handsomely and seemed such a willing beast that

I soon forgot her Confederate tricks, and would gladly have recommended

her for unconditional pardon. The former animal was not as young

and smooth-limbed as his chestnut-colored companion, but he strove

hard to keep an even whiffletree. Both appeared to feel an extra

exhilaration from the frosty air, for they shot along the beaten

snow-path with such astonishing swiftness that our movement might

almost have been compared to a railroad train, the smoke of my

f'riend's cigar, ascending in glorious white clouds, making the

figure more complete. We rode over a wild, undulating tract of

country, broken by a few scattering oaks, and here and there a

bold knoll or narrow ridge, but showing few houses. We saw not

more than three or four dwellings in a distance of fifteen miles.

Our horses stopped, after two or three hours of smart trotting,

before a small frame building, which, by a rude sign that hung

from a still ruder pole, surmounted by a martin-box, we learned

was the American House. The few houses scattered about constituted

the village of Princeton, an unpretending, honest-looking place,

and buttoned on to the dark skirts of the big woods. A man appeared

at the door of the hotel in his shirt-sleeves, and with his gray

head uncovered, whom my friend addressed as "Brother Golden,"

and invited us in. We complied readily, for I, at least, was a

good deal chilled. The prairie blast, which the hyperborean fiends

had that afternoon whetted to an uncommon sharpness, pierced even

my extra garments, making me sigh for some hospitable fire. "Brother

Golden" appreciated our want. With true landlordly cheer

he filled the long, high stove, which stood knee-deep in a box

of sand, with dry wood, and, as the flames roared their welcome

to the shivering travelers from "down river," he made

many inquiries, the last of which was, "Have you brought

me a paper?" My friend, remembering our good-natured landlord's

fondness for the latest news, and also that Uncle Sam can hardly

afford to send a mail-coach so near the big woods every day, had

filled his pockets with St. Paul and Minneapolis dailies, which

the old man accepted, and commenced devouring with a singular

relish.

As soon as the frost was thoroughly

melted out of us we donned our outer garments again and started

on. Leaving the village, we immediately crossed the "West

Branch" (of Rum River), and then struck into the woods, my

friend remarking that we should see no more signs of civilization,

except in the lumber-camps, until our return. As soon as the frost was thoroughly

melted out of us we donned our outer garments again and started

on. Leaving the village, we immediately crossed the "West

Branch" (of Rum River), and then struck into the woods, my

friend remarking that we should see no more signs of civilization,

except in the lumber-camps, until our return.

Until a comparatively recent period the vast forest before

us had remained undisturbed, save by the savage tribes who were

here when Columbus discovered America, and who still linger around

the old trails, reluctant to give them over to the devouring march

of the white man. A few years ago several enterprising citizens

of Maine found out by some means that extensive tracts of pine

lands were hid away here, and thus, aided by the knowledge they

had gained in connection with the lumber business in their native

State, they hastened to purchase these lands, content to wait

until the increasing population of Iowa, Southern Minnesota, and

other portions of the Mississippi Valley should, by their almost

limitless demand for building material, demonstrate the wisdom

of such a business course. Saw-mills were soon erected on the

St. Croix, at St. Anthony Falls, Minneapolis, and other points;

the lumber trade increased from year to year, until at last it

has grown into an importance which few can realize who have not

made a personal inspection. In addition to the Minnesota pineries

we need not mention those of Michigan and Wisconsin. Beginning

at well-known points in the latter States, the pine regions stretch

along the Chippewa and St. Croix, the shores of Lake Superior,

and across to the Mississippi below and above St. Cloud. Altogether

they form perhaps the most extensive pine forests in North America.

They have already become the sources of fabulous wealth, and afford

a theatre for the lumber business excelling any thing ever witnessed

in Maine or New Brunswick. To say nothing of how far Chicago outstrips

Bangor as a lumber mart, it may be observed that the scenes once

witnessed on the banks of the Penobscot, Kennebec, Androscoggin,

Saco, and Passamaquoddy, and in the palmiest days of these rivers,

have been transferred to the Mississippi, Chippewa, St. Croix,

and Rum River. The saw-mills at Minneapolis and St. Anthony turn

out annually over one hundred millions of feet of boards, and

are pushing the figures higher and higher every year; and thus

the same process which has demolished the forests of Maine, which

has scared the elk, and moose, and. beaver, and their elder brother,

the Indian, away from their Eastern haunts, is already far advanced

in the West.

Impressed with all of the above facts—remembering how

brief a period had elapsed since silence held undisputed sway

in the unpeopled shades before us, since a journey here seemed

more impossible to accomplish than a trip to Kane's Open Sea does

now, since I put my ten-year-old finger down on the map at a point

called St. Anthony Falls and thought it far enough away to be

included in the dimmest regions of romance, and yet, that peoples

from the other side of the Atlantic had already found this spot,

yea, were coming in annual thousands and selecting homes hundreds

of miles still nearer the setting sun—that an army of sturdy

emigrants from beyond the Baltic Sea, from the foot of the Alps,

and from the land of Erin, were waiting here, with axes in hand,

to hew down all these forests—remembering all this, the feelings

which crept over me as we left the open prairie and plunged into

the dark thick wilderness were strange and startling enough. And

our imagination at this moment was rendered more intense because

the night was coming on, and because we were riding under the

first pinetrees we had seen, whose leafy tops, swept by a strong

northwest wind, struck up a doleful music. We fancied that the

continual jingle of Kate's girdle of bells, the frosty murmur

of the sleigh-runners, and the occasional striking of the outer

ends of the whiffletrees against some trunk or bush that crowded

too near the road, must awaken unwelcome echoes in the dusky depths

about us, and that the lingering ghost of some Dakota savage might

possibly start up and defy our further intrusion upon, his old

hunting-grounds.

After a couple of hours' ride we came to a fork in the road,

and, for the first time, my friend was in doubt which way to go.

He stopped his horses, and we held a council. We looked about

for a finger-board, but found none. One road we knew led to Tidd's

Camp—the camp we were in search of—and the other to

somebody's else camp. The full moon peered out from a rift in

the clouds, and sprinkled its beams down through the oaks, poplars,

and pines, but not a ray of light penetrated our doubts. The trees

seemed to say, with provoking indifference, as we looked up at

them inquiringly, "We know how to stand here and grow; we

know how and when to open our buds and shed our leaves, and which

way to fall when we get old and rotten, or when the woodmen cut

us down; but we do not know the way to Tidd's Camp." George

and Kate threw their ears backward and forward, looked up one

road, then up the other, and finally, turning their heads round

at us, apparently confessed that their horse sense was as much

puzzled as our human sense; that although they would obey the

reins and go either way; they would rather not take the responsibility

of offering advice. The manner, however, in which they champed

their bits and pawed the snow showed that they were getting impatient

for a decision. We, too, desired to have the matter settled, for

we began to ache with cold, and felt a pressing need of shelter.

Our horses, in the mean time, had moved about half their length

toward the right, and for this reason, as much as any, we concluded

to take that direction, and started on. We had gone only two or

three miles before we learned our mistake—that the right

road was the wrong road, or again, that the right

road was the left road. We turned about, went back

to the fork, took the left road, and in half an hour came to a

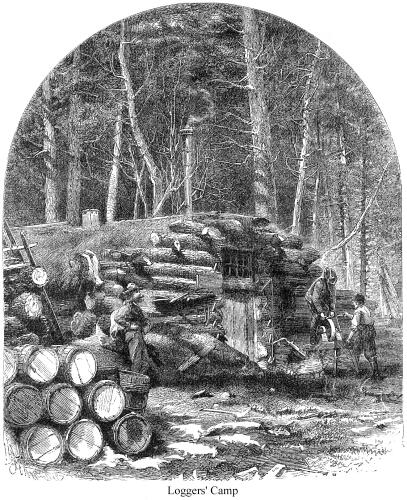

small circular opening, containing in its centre a clump of log-buildings,

which we at once pronounced to be Tidd's Camp. A column of smoke

with frequent sparks of fire pointed out the location of the lodgers'

building, and driving up before it, as we would have done before

a country hotel, my friend cried "Whoa!" in a tone which

he evidently intended the lodgers should hear as well as the horses.

Immediately a small door was partially opened, its wooden hinges

creaking with frost, when a man in a brown woolen shirt thrust

out his bushy head and exclaimed, "Hullo!" My friend

answered with a "Hullo!" This salutatory term, as used

by the first speaker, meant, when fully interpreted, "I am

one of the lodgers in Tidd's Camp; who are you?" As used

by the second speaker it meant, "I am one of the owners of

these pine forests, and have come up to see how my loggers are

getting on." The man in the door and the man in the sleigh

understood each other at once, and while the former put on his

hat and came out to take charge of the horses, the latter and

I went into the camp. Many of the sights which met my eyes on

entering were novel enough to one unacquainted with life in the

pineries. The thing I was most glad to see just then was the huge

fire in the centre of the camp, consuming a great pile of logs,

and sending its smoke through a large, square wooden chimney.

I stood before the hot, roaring flames, turned myself about, melting

first one side, then the other, and in the mean time took frequent

surveys of the apartment.

The camp was about thirty feet

long and twenty feet wide. Its ends and sides were constructed

of pine logs, notched at the ends, to enable them to lie closely,

and chinked with moss; the roof was made of pine splints, thatched

with mud, grass, etc. A small projection at the end opposite the

door, with a stove and pantry in it, was used as a cookroom. Across

the same end, next to the cook-room, but without any partition,

was a long space containing a rough table, hewed from a pine log,

set apart for the dining-room. The beds, or rather bed, for there

was no division in either the under or upper portion, was stretched

along on two sides of the fire, and so arranged that the sleepers'

heads nearly touched the opposite walls. I had heard the saying,

"thick as three in a bed," but here it was literally

as thick as a dozen in a bed. At the foot of the bed, between

the lodgers' feet and the fire, was a long, flat beam, called

the "Deacon's Seat." This Deacon's Seat is one of the

representative places in a lumberman's camp. It is a synonym for

a variety of scenes and memories. It is here that the logmen mount

themselves in the morning, after crawling from their bed of pine

boughs; here they sit and dress their feet, and from here they

drop off to their rest at night; here they arrange themselves

in a jolly row before the blazing fire, to make the long winter

evenings merry with their stories and jokes; here the visitor

at the camp is invited to sit and rest himself; here the men make

their bargains with the "boss," and receive their pay;

from this spot the logmen take their leave in the spring. And

thus the Deacon's Seat is associated with the whole interior life

of the camp, and is the magic word by which in after years one

logman reminds another of the events which transpired around the

log-fire in the distant pine woods. The camp was about thirty feet

long and twenty feet wide. Its ends and sides were constructed

of pine logs, notched at the ends, to enable them to lie closely,

and chinked with moss; the roof was made of pine splints, thatched

with mud, grass, etc. A small projection at the end opposite the

door, with a stove and pantry in it, was used as a cookroom. Across

the same end, next to the cook-room, but without any partition,

was a long space containing a rough table, hewed from a pine log,

set apart for the dining-room. The beds, or rather bed, for there

was no division in either the under or upper portion, was stretched

along on two sides of the fire, and so arranged that the sleepers'

heads nearly touched the opposite walls. I had heard the saying,

"thick as three in a bed," but here it was literally

as thick as a dozen in a bed. At the foot of the bed, between

the lodgers' feet and the fire, was a long, flat beam, called

the "Deacon's Seat." This Deacon's Seat is one of the

representative places in a lumberman's camp. It is a synonym for

a variety of scenes and memories. It is here that the logmen mount

themselves in the morning, after crawling from their bed of pine

boughs; here they sit and dress their feet, and from here they

drop off to their rest at night; here they arrange themselves

in a jolly row before the blazing fire, to make the long winter

evenings merry with their stories and jokes; here the visitor

at the camp is invited to sit and rest himself; here the men make

their bargains with the "boss," and receive their pay;

from this spot the logmen take their leave in the spring. And

thus the Deacon's Seat is associated with the whole interior life

of the camp, and is the magic word by which in after years one

logman reminds another of the events which transpired around the

log-fire in the distant pine woods.

The loggers had all retired except the cook and two or three

others; but none of them were asleep. Their long row of heads

under the low, slanting roof almost startled me, for each pair

of eyes, reflecting the flames that shot up from the middle of

the camp, glared at me like so many balls of fire. The men watched

my rotary motions before the burning logs as though they thought

I might be a piece of meat, and was trying to roast myself. They

lay on their sides, all facing one way, and packed as closely

as a bundle of spoons. If one turned, all turned. Now and then

some restless wit among them would effect a joke, and I could

hear the laugh roll round the whole camp, gathering extra force

at those points where it found the deepest appreciation. Now and

then one whose supper of salt pork and beans had left his mouth

parched would crawl out of his place, go straight to a barrel

in the corner of the camp, pour a dipper of ice-water down his

throat, then return, and after wedging himself in bed again, would

shut his eyes, as if ready now to be taken in charge by the fair,

gentle goddess who alike bends over the pillow of pine boughs

in a lumberman's camp and the downy couch of a king. I could imagine

only two things to prevent perfect sleep—a too hearty supper

and too little space for the body. The arrangement for ventilation

was ample. No "modern house with modern conveniences"

I ever saw can equal a logger's camp in this respect. The big,

square, open chimney, aided by a constant fire underneath, keeps

up an immense draught, and renders the air as pure as the outdoor

atmosphere itself. I recommend such a place as a hospital for

consumptives. Oh ye pulmonary sufferers, throw away your bottles

of quackery, your "Cod Liver Oil," etc., and spend a

winter with the happy logmen in a camp; try a tonic of pine boughs.

After a half hour or so the cook,

a tall, dark-haired, rather intelligent-looking Frenchman, announced

that our supper was ready. We took our seats on a rude bench,

and at a table which never came from a cabinet shop and never

saw a table-cloth, but which had on it now a dish of smoking-hot

beans, two tin basins of warm tea, some excellent raised biscuits,

etc. There was no milk for the tea, and no butter for the biscuits,

but the long, cold ride had sharpened our appetites so much that

extras were not needed to give what was before us the desired

relish. As we drank our tea and ate heartily of the pork and beans

my friend described to me the process of cooking the latter. Pointing

to a spot at the end of the log-fire and near us, he showed me

a huge iron pot filled with beans and covered tightly, and which

is buried every night in the hot ashes, where the cooking operation

goes on, and during the hours in which the consumers of these

staple edibles are snoring off the effects of yesterday's meals.

Good judges say that this manner of preparing beans for the table

is much superior to any other. I am ready to testify to the excellent

quality of those I ate—a little too rich they were for my

dyspeptic stomach—at least they were, somewhat too highly

seasoned with pork fat. But a lumberman's stomach can digest three

meals a day of them, fat and all, and without fear of the nightmare.

Nothing can swing an axe, or move a saw, or roll logs, like baked

beans. No logger who has free access to that iron pot in the ashes

complains of exhaustion. A Connecticut preacher, in the olden

times, tried to compute the number of bushels of baked beans he

had preached to on Sunday during a ministry of forty years. I

wonder how many bushels are carried into the pineries every winter! After a half hour or so the cook,

a tall, dark-haired, rather intelligent-looking Frenchman, announced

that our supper was ready. We took our seats on a rude bench,

and at a table which never came from a cabinet shop and never

saw a table-cloth, but which had on it now a dish of smoking-hot

beans, two tin basins of warm tea, some excellent raised biscuits,

etc. There was no milk for the tea, and no butter for the biscuits,

but the long, cold ride had sharpened our appetites so much that

extras were not needed to give what was before us the desired

relish. As we drank our tea and ate heartily of the pork and beans

my friend described to me the process of cooking the latter. Pointing

to a spot at the end of the log-fire and near us, he showed me

a huge iron pot filled with beans and covered tightly, and which

is buried every night in the hot ashes, where the cooking operation

goes on, and during the hours in which the consumers of these

staple edibles are snoring off the effects of yesterday's meals.

Good judges say that this manner of preparing beans for the table

is much superior to any other. I am ready to testify to the excellent

quality of those I ate—a little too rich they were for my

dyspeptic stomach—at least they were, somewhat too highly

seasoned with pork fat. But a lumberman's stomach can digest three

meals a day of them, fat and all, and without fear of the nightmare.

Nothing can swing an axe, or move a saw, or roll logs, like baked

beans. No logger who has free access to that iron pot in the ashes

complains of exhaustion. A Connecticut preacher, in the olden

times, tried to compute the number of bushels of baked beans he

had preached to on Sunday during a ministry of forty years. I

wonder how many bushels are carried into the pineries every winter!

Our repast being ended, we began to think of retiring; but

where shall we sleep? we asked ourselves dubiously. There were

two beds only, and these were full. The problem was solved when

our cook had laid down a buffalo-robe on the uneven floor and

asked us to stretch ourselves there. With another buffalo-robe

for our covering, and with our shawls folded for pillows, the

prospect for a good night's rest was quite encouraging. My friend

took the side next the fire, where his danger of being; burned

was about equal to mine of being frozen; but neither of us suffered

much. If I dreamed of any thing, it must have been of stockings,

socks, and moccasins, as not less than a hundred pairs of these

pedal coverings were hanging against the roof, partially over

the fire, and exactly in range of my eyes as I had fixed myself

for sleep; and being a little nervous from my long ride and late

supper, I was obliged to lie awake an hour or more and study this

singular sight. Calling my friend's attention to the  matter,

I asked if we were not in a stocking-factory or a moccasin-store

instead of a lumberman's forest-house. He replied that "the

loggers are obliged to take good care of their feet; that one

of them often wears three or four pairs of socks, with a pair

of moccasins over them; that the moccasins, because they give

the feet more freedom, rendering them less liable to freeze, are

generally preferred to coarse leather boots. Those you see hanging

there will disappear in the morning, because they will all be

pulled on to their owners' feet and walked off into the woods.

To-morrow night they will be hung up in the same places to dry

again; although, as the snow in this northern latitude is generally

very dry, they seldom get wet much," I listened to my friend's

explanation with deep interest, suggesting to myself that if all

persons would take as much pains to protect their feet against

cold and wet, consumption would be cheated of a majority of its

victims. matter,

I asked if we were not in a stocking-factory or a moccasin-store

instead of a lumberman's forest-house. He replied that "the

loggers are obliged to take good care of their feet; that one

of them often wears three or four pairs of socks, with a pair

of moccasins over them; that the moccasins, because they give

the feet more freedom, rendering them less liable to freeze, are

generally preferred to coarse leather boots. Those you see hanging

there will disappear in the morning, because they will all be

pulled on to their owners' feet and walked off into the woods.

To-morrow night they will be hung up in the same places to dry

again; although, as the snow in this northern latitude is generally

very dry, they seldom get wet much," I listened to my friend's

explanation with deep interest, suggesting to myself that if all

persons would take as much pains to protect their feet against

cold and wet, consumption would be cheated of a majority of its

victims.

A feeling of drowsiness seized me at last, and as the camp

was still, save the occasional snoring of the loggers and the

falling of a firebrand now and then, the hundred pairs of stockings

faded slowly from my vision, and I dropped off into a sleep, wondering

at the latest point of consciousness if St. Nicholas ever visits

a lumberman's camp, and if so, if he feels himself bound to stuff

every woolen leg he finds there with Christmas gifts!

We rose in the morning soon after daylight. The workmen had

already cleared the line over the fire of its burden of stockings,

and were walking about the camp with muffled feet, preparing for

breakfast. The fire, which had been allowed to smoulder and go

partially out during the night, had received a fresh supply of

logs, and brought the room into such a comfortable degree of warmth

we could hardly believe the statement made by one of the men that

the thermometer, hanging against the log-barn, showed the mercury

to be twenty-four degrees below zero. The cook disentombed the

iron pot, dished out a quantity of beans, and putting them on

the table, with a few other eatables, announced that breakfast

was ready. The men ate rapidly, and with an appetite that is enjoyed

by those only who gain their bread by the sweat of the face. Very

little was said during the meal, and each one, as soon as he had

finished, rose and departed to his day's work.

About ten o'clock our horses were harnessed, and we started

for Moses's Camp, on Tibbet's Brook, forty miles distant. The

air was quite still low down in the woods, but the soughing pine-tops

told plainly that a furious gale was raging out on the unsheltered

prairie. Notwithstanding the protection which the forest afforded,

we found it necessary to seek the still further aid of all our

extra clothing to keep out the intense cold; and whenever we came

to the bank of a stream, or some other opening where the wind

had a fair chance at us, our faces tingled with frost, and we

wept tears of ice. Our horses bounded forward as gayly as reindeers,

while the frost hung their nostrils full of stalactites, and ornamented

parts of their bodies with silver-tipped hairs.

We reached Lowell's Camp, on

the "East Branch," at twelve o'clock, and Moses's Camp

a little before dark. The air of comfort and welcome which greeted

us on entering the latter forest home seemed all the more agreeable

on account of the extremely inhospitable day we had braved to

get there. We reached Lowell's Camp, on

the "East Branch," at twelve o'clock, and Moses's Camp

a little before dark. The air of comfort and welcome which greeted

us on entering the latter forest home seemed all the more agreeable

on account of the extremely inhospitable day we had braved to

get there.

The interior of this camp differed from Tidd's Camp in some

respects. It was warmed by a large stove instead of an open fire,

and thus it dispensed with that splendid ventilator, the big chimney.

Then it had the addition of a cellar; of more complete cooking

arrangements; in short, it was a more stylish, aristocratic establishment

than the first. It evidently belonged to the Fifth Avenue of the

pineries. Two clocks, one an alarm-clock, stood side by side on

a shelf; the pantry displayed a fine assortment of tin dishes;

and the Deacon's Seat was smooth and nice. Over the window, at

the east end of the camp, and on the kitchen walls, was a large

advertisement, telling the woods people that Beecher and Spurgeon

are the "two greatest preachers in the world," and that

"their sermons are published every week in the Examiner

and Chronicle!" Who can doubt the peerless ability of

these pulpit orators, or the wonderful enterprise of their publishers,

after seeing such an advertisement posted on the walls of a forester's

cabin in the far off Minnesota Pineries ?

The cook at this camp I soon discovered was to the "manner

born." He moved about in his white apron with an educated

air, and seemed as cleanly and genteel and affable as though he

had just been transferred from the Astor House. He had nothing

but tin dishes to set off his table with, but these were kept

bright and clean; and the food, well cooked, was brought on with

as much precision and style as his humble cuisine would

allow. His biscuits were light and palatable; his gingerbread

was excellent; his tea was delicious. Besides these he gave the

men nice boiled beef, the everlasting dish of beans (though these

were not baked in the ground), and stewed cranberries. He gave

them butter and milk also—the latter luxury they owed to

a good cow kept in one of the log-stables, and which was driven

into the woods at the beginning of winter.

Thirty fine-looking, healthy, robust, well-behaved men sat

down at the supper-table, and who, when their appetites were sated,

broke up the evening in various ways. Some mended their clothes,

some darned their socks, some, using the sinews of the deer, obtained

of the Indians, for thread, repaired their moccasins, while others

employed their time in reading. The hours were relieved, too,

by a little entertainment in the shape of music and dancing. One

young man, who had swung the axe all day, rosined up his bow and

gave us a few lively airs on his fiddle, while two other logmen,

who had tramped in twelve inches of snow since the early morn,

engaged in a "double shuffle," or something of the kind,

on one of the planks of the floor. A pleasant-voiced son of Erin

sang two or three songs, substituting simple musical sounds where

he was unable to recall the words. Others still filled the intervals

between the music with conversation on a variety of topics, breaking

out now and then in loud, hearty laughter. One Scandinavian youth,

busily patching his pants, which had suffered by their contact

with pine-knots, interested several listeners with some neighborhood

gossip he had treasured up with singular minuteness, concerning

a hidden pot of gold, and a ghost which kept watch over it, frightening

those who came to dig for the treasure.

Of course a camp full of woodmen

could hardly be expected to pass a whole evening on the "Deacon's

Seat," around the big stove, without more or less indulgence

in tobacco. A large number puffed away at their meerschaums, or

their short, black, clay pipes, looking a kind of quiet content,

and as if the weariness they brought in from their day's work

were really taking flight in clouds of smoke. No stimulants stronger

than tobacco and tea were allowed in the pineries; the woods had

not yet received enough of the influence of civilization to admit

a bar within their hallowed shades. Of course a camp full of woodmen

could hardly be expected to pass a whole evening on the "Deacon's

Seat," around the big stove, without more or less indulgence

in tobacco. A large number puffed away at their meerschaums, or

their short, black, clay pipes, looking a kind of quiet content,

and as if the weariness they brought in from their day's work

were really taking flight in clouds of smoke. No stimulants stronger

than tobacco and tea were allowed in the pineries; the woods had

not yet received enough of the influence of civilization to admit

a bar within their hallowed shades.

At ten o'clock the signal for retiring was given. A half hour

later and most of the logmen were snoring—perhaps dreaming

of friends "down the river." At half past five in the

morning the alarm-clock put an end to snoring and dreaming, and

called the men from their beds again.

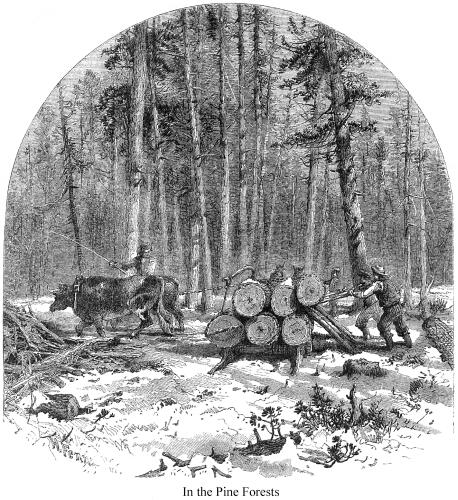

As soon as breakfast was dispatched the workmen divided themselves

into separate squads, according to their respective charges, and

went to their labors: one squad to drive the teams; another, the

"choppers," to fell the trees; another, the "swampers,"

to prepare the roads; another, the "sawyers," to saw

the trees into logs. Notwithstanding the mercury was still at

a frightful distance below zero my friend and I followed on—he

to see how his men had got along, how many logs bad been hauled,

etc.; I to obtain a little information concerning the logging

business. We had gone but a few rods when we made the discovery,

by some tracks in the snow, that a couple of wolves had been prowling

about our camp during the night. Why they did not come nearer,

give us their usual lupine serenade, and even thrust their noses

into the door, we did not understand. This was the nearest we

came to seeing any wild beasts during our stay in the woods. We

hoped to meet some deer, as their tracks were plenty every where,

but we did not happen to see one. Very much to our disappointment,

we saw only one wild Indian. This one, as he stepped out of the

road to let us pass, frightened our horses terribly with the great

white blanket thrown over his head. It is said that horses dislike

the peculiar scent that Indians carry about their persons and

clothes.

Within a quarter of a mile of

the camp we came where the pines stood thick and tall, and handsome

enough to delight any lumberman's eyes. Hundreds of splendid symmetrical

trunks might have been counted without changing our position;

and one could almost fancy, as he looked out among them, that

they were the columns of some old and endless temple, their dark

and shaggy tops forming the lofty roof, and the snow beneath the

white marble floor. Often three or four trees of about equal size

were seen standing close together in a cluster, as though they

sprang from kindred germs, and had cherished a common sympathy

through their hundred years of growth; generally, however, those

large enough for use were half a dozen yards apart—sometimes

as many rods. Scattered between them were a few oaks, iron-wood,

and birch—the latter ornamented with the usual fringes and

curls. All the timber here, except the pine, is valueless. Although

wood is worth, when cut, from $6 to $10 a cord in Minneapolis

and St. Paul, it is not worth ten cents a cord on Tibbet's Brook,

because there is no means for transporting it to places where

it is wanted. Even the land itself will, in many cases, be abandoned

to the tax claims as soon as it is cleared of pine. Within a quarter of a mile of

the camp we came where the pines stood thick and tall, and handsome

enough to delight any lumberman's eyes. Hundreds of splendid symmetrical

trunks might have been counted without changing our position;

and one could almost fancy, as he looked out among them, that

they were the columns of some old and endless temple, their dark

and shaggy tops forming the lofty roof, and the snow beneath the

white marble floor. Often three or four trees of about equal size

were seen standing close together in a cluster, as though they

sprang from kindred germs, and had cherished a common sympathy

through their hundred years of growth; generally, however, those

large enough for use were half a dozen yards apart—sometimes

as many rods. Scattered between them were a few oaks, iron-wood,

and birch—the latter ornamented with the usual fringes and

curls. All the timber here, except the pine, is valueless. Although

wood is worth, when cut, from $6 to $10 a cord in Minneapolis

and St. Paul, it is not worth ten cents a cord on Tibbet's Brook,

because there is no means for transporting it to places where

it is wanted. Even the land itself will, in many cases, be abandoned

to the tax claims as soon as it is cleared of pine.

Notwithstanding the general excellence of the pines which stretched

away in grand perspective on every side, there were many, of course,

unfit for use. Some were short and scraggy; some were "shaky;"

and some were old and rotten. Marsh, in his article on the "Quality

of Timber," says: "The white pine, Pinus Strobus, for

instance, and other trees of similar character and uses, require

for their perfect growth a density of forest vegetation around

them, which protects them from too much agitation by the winds,

and from the persistence of the lateral branches, which fill the

wood with knots. A pine which has grown under these conditions

possesses a tall, straight stem, admirably fitted for masts and

spars; and at the same time its wood is almost wholly free from

knots, is regular in its annular structure, soft and uniform in

texture, and consequently superior to almost all other timber

for joinery. If, while a large pine is spared, the broad-leaved

or other smaller trees around it are felled, the swaying of the

tree from the action of the wind mechanically produces separation

between the layers of annual growth, and greatly diminishes the

value of the timber. The same defect is often observed in pines

which, from accident of growth, have over-topped their fellows

in the virgin forest. The white pine growing in the fields or

open glades in the woods is totally different from the true forest

tree, both in general aspect and quality of wood. Its stem is

much shorter, its top is less tapering, its foliage is denser

and more inclined to gather into tufts, its branches more numerous

and of larger diameter, its wood shows much more distinctly the

divisions of annular growth, is of coarser grain, harder, and

more difficult to work into mitre joints. Intermixed with the

most valuable pines in the American forests are many trees of

the character I have just described. The lumbermen call them 'saplings,'

and generally regard them as different in species from the true

white pine, but botanists are unable to establish a distinction

between them, and as they agree in almost all respects with trees

grown in the open grounds from white pine seedlings, I believe

their peculiar character is due to unfavorable circumstances in

their early growth. The pine, then, is an exception to the general

rule as to the inferiority of the forest to the open-ground tree."

The truth of much, if not all,

of this quotation was verified wherever we made an observation.

The tallest, straightest, finest pines we saw, those freest from

limbs and knots, among which the logmen seemed to revel like a

herd of oxen just let loose in a full-grown field of Illinois

corn, were found in the densest portions of the woods, where the

shade was so great and the atmosphere so dank that a ray of sunlight

could hardly penetrate there. The low, scraggy growths, whose

unmannered trunks gave them immunity from the ruthless axe, were

generally situated in more open places, and at greater distances

from each other. The thicker the neighborhood the statelier and

loftier grew each individual tree, as though it took a kind of

pride in outdoing its fellows. Sometimes a tree which had a fair

outside, like the hypocrite among men, was shaky and hollow within;

and as we have certain methods of testing the virtue of human

pretensions, so the chopper had a way of sounding his tree, determining

its internal condition often by the first stroke of the axe; besides,

he could detect the lumber qualities of a tree by his experienced

eye, to which patches of lichens and certain colored fungi attached

to the bark as surely revealed a concealed rottenness as the scarlet

excrescences on a drunkard's nose divulge the fact of an unsound

life. The truth of much, if not all,

of this quotation was verified wherever we made an observation.

The tallest, straightest, finest pines we saw, those freest from

limbs and knots, among which the logmen seemed to revel like a

herd of oxen just let loose in a full-grown field of Illinois

corn, were found in the densest portions of the woods, where the

shade was so great and the atmosphere so dank that a ray of sunlight

could hardly penetrate there. The low, scraggy growths, whose

unmannered trunks gave them immunity from the ruthless axe, were

generally situated in more open places, and at greater distances

from each other. The thicker the neighborhood the statelier and

loftier grew each individual tree, as though it took a kind of

pride in outdoing its fellows. Sometimes a tree which had a fair

outside, like the hypocrite among men, was shaky and hollow within;

and as we have certain methods of testing the virtue of human

pretensions, so the chopper had a way of sounding his tree, determining

its internal condition often by the first stroke of the axe; besides,

he could detect the lumber qualities of a tree by his experienced

eye, to which patches of lichens and certain colored fungi attached

to the bark as surely revealed a concealed rottenness as the scarlet

excrescences on a drunkard's nose divulge the fact of an unsound

life.

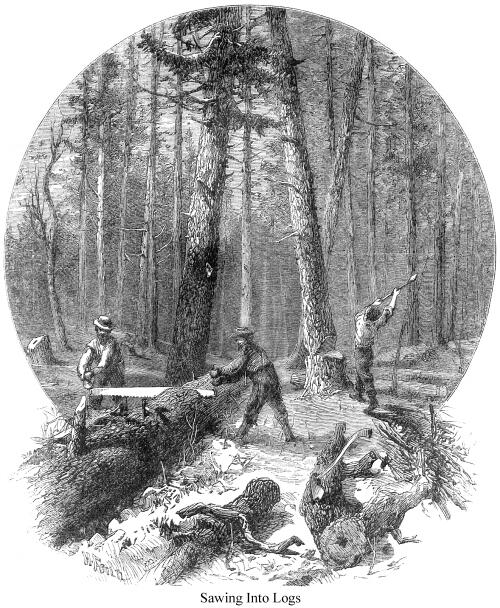

Following close upon the "choppers," who did nothing

but fell the trees and trim them, came the "sawyers."

Two men standing on opposite sides of a prostrate tree, a few

feet apart, and facing each other, one with his right and the

other with his left foot advanced grasp the upright handles of

a cross-cut saw, and drawing it backward and forward with an easy,

regular motion, expelling the saw-dust, whose piny odor is pleasant

to a lumberman's nostrils, into a heap on either side of the tree,

they sever the trunk into logs of various lengths. Next came the

"swampers," who prepared the roads for the teams which

were waiting to draw the logs away to the landing.

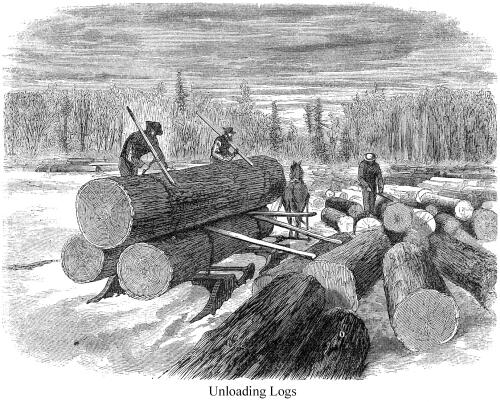

I watched the "loading" process with a deep interest,

as I saw here how intellect, as every where else, has triumphed

over mere brute force. The time was, and not many years ago, when

logmen had little to aid them in getting their logs on to a sled

besides their own hands. There was then no alternative but the

hardest kind of lugging and lifting; but all that has changed.

Using a log-chain, which is attached to the middle of the log

in such a way as to get a purchase on the latter, and cause it

to roll when  the chain is pulled,

the logman now makes the oxen do the lifting, while he superintends

the operation and applies a little brain work. Six large logs

were piled on to one sled in a few moments of time, two or three

men assisting with their "cant-dogs," the whole costing

as little manual effort as the laying together of an equal number

of common fence-rails. The sleds used were at least one-third

wider than common sleds, and hence they made a very wide path.

Along this "broad gauge" we followed the teams to see

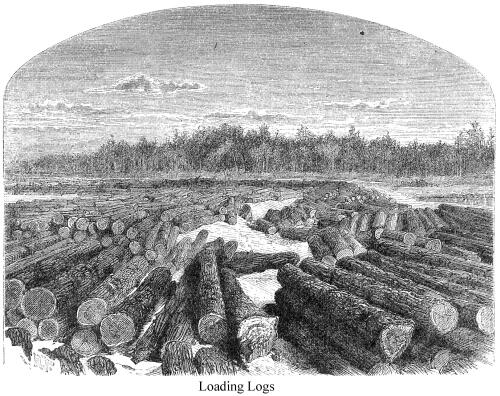

where the logs were deposited. After a few minutes' walk we emerged

from the thick timber into an opening through which ran Tibbet's

Brook. Here was what was called the "landing." Standing

on the banks of that winter-bound brook we could see thousands

of logs which had been cut and hauled from the surrounding forests.

Counted in feet the logs we saw at a single view numbered between

four and five millions! It was a splendid sight. My friend, who

owned them all, and as many more besides, whose mill at Minneapolis,

a hundred miles below, was ready to convert these logs into sawed

lumber, worth on an average twenty dollars per thousand feet,

must have enjoyed the spectacle even more than I. the chain is pulled,

the logman now makes the oxen do the lifting, while he superintends

the operation and applies a little brain work. Six large logs

were piled on to one sled in a few moments of time, two or three

men assisting with their "cant-dogs," the whole costing

as little manual effort as the laying together of an equal number

of common fence-rails. The sleds used were at least one-third

wider than common sleds, and hence they made a very wide path.

Along this "broad gauge" we followed the teams to see

where the logs were deposited. After a few minutes' walk we emerged

from the thick timber into an opening through which ran Tibbet's

Brook. Here was what was called the "landing." Standing

on the banks of that winter-bound brook we could see thousands

of logs which had been cut and hauled from the surrounding forests.

Counted in feet the logs we saw at a single view numbered between

four and five millions! It was a splendid sight. My friend, who

owned them all, and as many more besides, whose mill at Minneapolis,

a hundred miles below, was ready to convert these logs into sawed

lumber, worth on an average twenty dollars per thousand feet,

must have enjoyed the spectacle even more than I.

In order for the reader to gain any adequate idea of the lumber

interests carried on in these woods it should be observed that

there were a great many other landings scattered about in different

sections and on various streams, perhaps fifty in all, similar

to the one I have mentioned—some smaller and some larger.

Nearly or quite an equal number might have been found on the Upper

Mississippi itself above St. Cloud. In both pineries, the Upper

Mississippi and Rum River, from eight hundred to a thousand men

were employed, and not far from one hundred millions of feet of

logs were secured during the winter.

The streams spoken of, on which "landings" are made,

are numerous, and traverse an extensive tract of country, intersecting

everywhere rich pine regions, and serving as outlets to the thousands

of logs that are rolled over their banks. Although many of these

streams, at certain seasons of the year, are so shallow and muddy

that an Indian can not navigate them in his birch canoe, yea,

that a common teal duck can not find enough depth of water to

swim there, yet when swollen by the spring thaws each one bears

away on its bosom great argosies of wealth, and becomes in the

lumbermen's eyes a modern Pactolus. In some instances the pines

grow very near the streams, and the trouble of hauling the logs

is slight; but often they are brought three or four miles. The

hauling distance, for obvious reasons, will increase from year

to year.

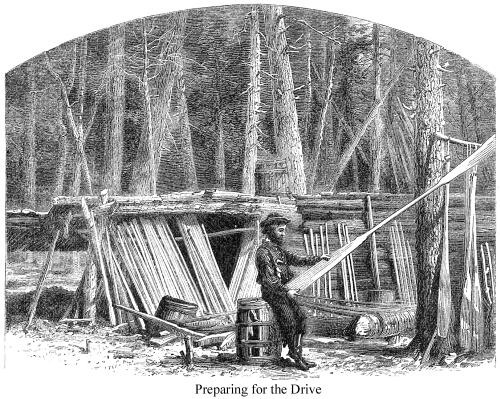

The process of moving the logs from their winter "landings"

down the streams to Minneapolis and St. Anthony is called the

"drive." The operation begins as soon as the snows are

melted and the streams, augmented by the spring freshets, are

high enough to float the logs. In those instances where the stream

is too shallow and feeble to lift the logs, even with the help

referred to, a dam is built across it, and from the waters thus

temporarily deepened the logs are pushed forward a considerable

distance to a point where they must wait, it may be, for the erection

of another dam. By repeating this slow, tedious, and expensive

work the logs are moved along into the river, where they float

with less trouble. Some of the brooks are deep enough at the start

without any dam. It is a magnificent sight to see the thousands

of logs as they come down out of the forest, swimming along singly

or in large masses, into the main body of Ram River at Princeton.

The surface of the river below this point is sometimes entirely

covered for a distance of twenty-five miles.

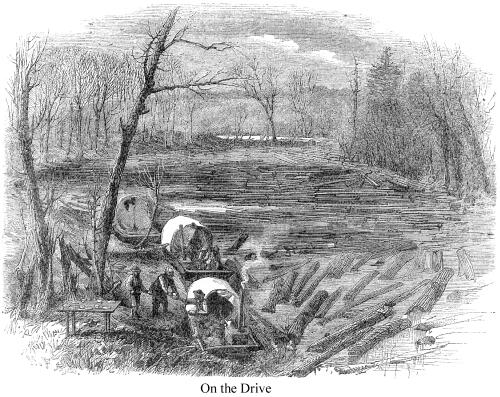

The men employed on the "drive,"

and who, for the most part, are men who spent the winter in the

woods, and who consent to engage in this business at considerably

increased wages, divide themselves into separate squads, and proceeding

along the river, urge the logs forward as rapidly as possible. The men employed on the "drive,"

and who, for the most part, are men who spent the winter in the

woods, and who consent to engage in this business at considerably

increased wages, divide themselves into separate squads, and proceeding

along the river, urge the logs forward as rapidly as possible.

Behind the whole line of operations, or behind each regiment

of logs, follows the "waugan"—a small boat or barge

with a canvas awning stretched over it, and carrying the cook,

cooking-utensils, and supplies for the men. At the meal-hour,

which occurs four times a day, the "waugan" hauls up

to the bank, fastens her bow to a tree, when the cook spreads

his table on the shore and blows his horn—the echoes of which,

as they sound along the winding stream, call the weary men to

their ample repast of hot tea and baked beans. At each sunset

the captain of the "waugan," having moored his craft

to the shore again, selects a proper spot and erects a tent, under

which the men spend the night. A big, hot fire in front of the

tent keeps off the night chill.

The men by long practice on the "drive" become very

expert in their business. They balance themselves on floating

logs and leap from one to another of these precarious footings

with the agility and skill of circus-riders, while green hands

would be sure of a ducking every few minutes, if they did not

meet with the worse fate of breaking their necks. If a log lodges

on a rock in the middle of the stream, the nearest man plunges

into the water, often waist-deep, and wading out to it catches

hold of the refractory member with his "cant-dog"—a

short hand-spike with an adjustable iron hook attached to the

end—and hurls it quickly into the channel again, when it

darts forward after its fellows. If the water is too deep for

wading, an experienced oarsman puts off toward the points of obstruction

in a "batteau"—a long, slim, red boat, which shoots

over the waves with the ease and swiftness of an Indian's arrow.

This boat is handled by a single oar, is not easily upset, will

stand any amount of jamming against stones, can swim in the shallowest

places, and ride safely down the most dangerous rapids. Sometimes

several men may be seen in it, standing, and pushing it about

with long poles. Whether it is moored under the banks, or left

to float at will on some circumfluous wave along the margin of

the river, or making its diagonal trips from shore to shore, or

running in and out of the spaces between the floating logs, the

"batteau" forms one of the most novel, picturesque,

and stirring things which one will encounter in a "drive."

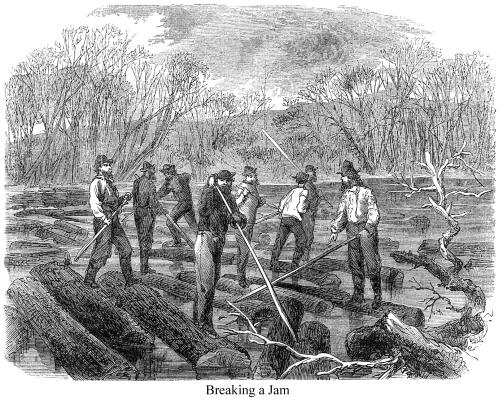

Often, while making a turn in the river, the immense mass of

logs crowd so close upon each other that they fill the whole space

between the shores, and form a vast wedge, or, in the vernacular

of lumbermen, a "jam," and which, until it is broken,

prevents any further progress of the logs; as soon, therefore,

as this "jam" happens a score of men, with their "cant-dogs"

in hand, rush on to the obstructed logs, and loosening a few of

the front ones, put the whole in motion once more.

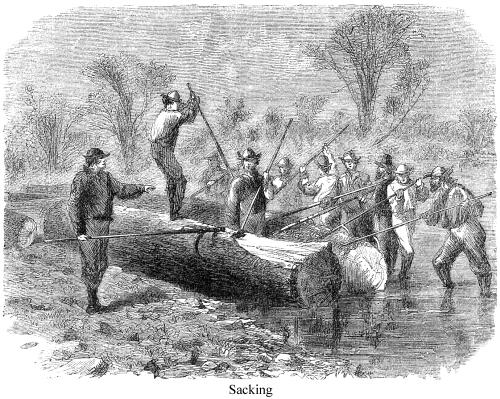

Another frequent and laborious part of the "drive"

is "sacking." This takes place when the logs, by means

of a rapid current at a bend in the river, or from some other

cause, have been thrown up and lodged upon the shore. To get them

back again into the river, three or four, often half a dozen,

men seize each log with their "cant-dogs," and absolutely

lift it or drag it along the mud and sand a considerable distance.

And thus, by "sacking," breaking "jams,"

wading and dislodging stragglers, pushing the shore logs toward

the middle of the current, rowing here and there in the batteau,

and tumbling such pines as had perched themselves high and dry

on some projecting bank or stone—by all these processes,

repeated day by day, the whole "drive" is advanced until;

after a few weeks, it reaches the "booms" prepared for

it at the mouth of the Rum River and at other points on the Mississippi

near the  Minneapolis and St. Anthony mills.

Passing down Tibbet's Brook a short distance we came to Moses's

lower "landing," which differed from the other in no

important particular except that it contained a few logs of enormous

size. On the butt end of the largest one we counted two hundred

and fifty annular rings! Thus the tree from which it was

taken was born about the year that William Shakspeare died and

Oliver Cromwell matriculated at Sussex College. It was four or

five years old when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock; and

was a flourishing youth of fifty when John Milton went quietly

to sleep in his house at Bunhill Fields; it had stretched its

green top up to a magnificent height, and was able to boast of

an experience of nearly one hundred and fifty years when the famous

and infamous "Stamp Act" was passed, and before Ohio,

Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan claimed even a territorial government;

its two-hundredth birthday had passed before a single white man

had come to admire its giant trunk, and before its " topmost

branches," peering over the shoulders of younger pines, could

see beyond the "Land of the Dakotas." How cruel that

a civilization so long waited for should signal its approach by

ordering her first hardy skirmishers to cut this patriarch of

the forest down, and to bring in its dismembered parts as a trophy

of the ever-widening circle of her conquests! Two centuries and

a half of patient growing to be torn asunder in a moment by irreverent

saws, and to serve the cupidity of a race that turns all the natural

waterfalls into milldams, and the forests into lumber-yards! Minneapolis and St. Anthony mills.

Passing down Tibbet's Brook a short distance we came to Moses's

lower "landing," which differed from the other in no

important particular except that it contained a few logs of enormous

size. On the butt end of the largest one we counted two hundred

and fifty annular rings! Thus the tree from which it was

taken was born about the year that William Shakspeare died and

Oliver Cromwell matriculated at Sussex College. It was four or

five years old when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock; and

was a flourishing youth of fifty when John Milton went quietly

to sleep in his house at Bunhill Fields; it had stretched its

green top up to a magnificent height, and was able to boast of

an experience of nearly one hundred and fifty years when the famous

and infamous "Stamp Act" was passed, and before Ohio,

Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan claimed even a territorial government;

its two-hundredth birthday had passed before a single white man

had come to admire its giant trunk, and before its " topmost

branches," peering over the shoulders of younger pines, could

see beyond the "Land of the Dakotas." How cruel that

a civilization so long waited for should signal its approach by

ordering her first hardy skirmishers to cut this patriarch of

the forest down, and to bring in its dismembered parts as a trophy

of the ever-widening circle of her conquests! Two centuries and

a half of patient growing to be torn asunder in a moment by irreverent

saws, and to serve the cupidity of a race that turns all the natural

waterfalls into milldams, and the forests into lumber-yards!

To what degree of longevity this tree might have attained if

it had been left to its natural course is uncertain, but we could

discover no signs of decay, internal or external. Dr. Williams,

who is quoted by Mr. Marsh, says he found "pines four hundred

years old," and that a friend of his discovered soiree "much

older." So it is probable that our tree might have survived

another term of two hundred years. In that case what other changes

would it have witnessed in this country before its branches rotted

and its heart became worm-eaten and dead?

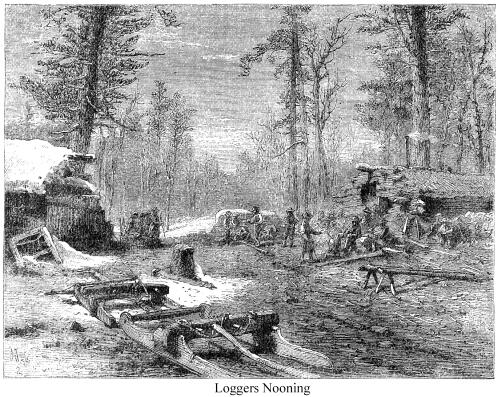

At twelve o'clock all the men returned to the camp for "nooning."

The horses and oxen were unloosed from the sleds, driven into

the log-barn, and fed with hay and oats, while the workmen sat

down with huge appetites to their savory dishes of beans. My friend

and I, dreading to encounter the stinging air again, spent the

afternoon on the Deacon's Seat, close by the camp stove. The following

morning we bade adieu to our camp friends, who had entertained

us so generously, and started for home by way of St. Cloud. Our

road, which struck off in a westerly course, led us in a little

while across the "West Branch" of Rum River, and along

by the door of Brown's Camp. The sun shone clear in the cold March

sky, dropping a beam now and then through the dense boughs upon

the quiet snow, which was spread like a white carpet on the floor

of the woods. The air, although a little more pungent than one

might wish, was brisk and healthy, causing our frames to tingle

with inexpressible delight. A more charming, inspiring, invigorating

morning's ride than this can hardly be imagined. The road, much

of the time, wound through a majestic colonnade of pines, whose

branches formed splendid arches over our heads, and threw down

the most welcome odor. Altogether we seemed to be riding through

an enchanted forest. The scene was mightily changed, however,

the moment we emerged from the woods and began to cross the open

prairie east of St. Cloud. The wind, seeming to seek revenge for

our temporary escape from its power, swept upon us with merciless

fury, and we were obliged to cover our faces to keep them from

instant freezing.

We at last reached St. Cloud at two o'clock. After a rest of

two hours we drove to Clear Water, where we spent the night. The

next day about five o'clock p.m. we arrived in Minneapolis, having

ridden two hundred miles during the five days of our absence,

and all but thirty miles of the distance in a sleigh, the thermometer

keeping far enough below zero all the while to make it one of

the coldest weeks ever experienced by Minnesotians in the month

of March.

Logging Page

| Contents Page

|