|

THE RAILROADS

and THE MAILS

Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the first

Government-issued Postage Stamps for the

United States of America.

GRAND CENTRAL PALACE

NEW YORK, N.Y.

May 17th thru May 25th 1947

CHESAPEAKE & OHIO LINES

TRANSPORTATION of letters has been a concern of mankind for

at least five or six thousand years. In fact, if Adam was created

in the year 4004 before Christ, he was only about two hundred

years old when the first postal system was instituted. King Sargon

of Babylon reigned about 3800 B.C. He established a regular postal

service for his official letters, which he sent to his correspondents

everywhere in the world as it was then known. The Chinese had

not by that time invented paper, the king of Pergamum had not

developed parchment as writing material, nor the Egyptians the

pith of the papyrus plant. So the king's letters were cut on small

slabs of soft clay, which was then baked hard, covered with a

softer clay for protection, and then marked with the royal seal.

Here we see the counterpart of our modem envelopes—the soft

enveloping clay—and of our postage stamps—the king's

seal. The royal couriers were the postmen of these ancient times.

Specimens of these ancient letters may now be seen in the Louvre

in Paris. From then on, we have postal history almost unbroken.

The kings of Egypt regarded the post as so important that there

are postmen depicted on the walls of a royal tomb dating about

1500 B.C. The Old Testament contains many, references to the post.

Herodotus, writing in the fifth century B.C., is the author of

that famous motto which appears—translated from the Greek

original—on the front of the New York post-office:

"Neither rain, nor snow, nor heat, nor gloom of night

stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed

rounds."

The Romans had an elaborate postal system, which continued

until the Dark Ages almost put a stop to civilization.

WRITING BECOMES MORE GENERAL

In the time of the Renaissance letter-writing gradually became

more general, and regular postal systems were developed on the

Continent of Europe and in the British Isles. Transportation,

however, was still subject to the limitations of foot-couriers

or riders on horseback, and this made the sending of a letter

a very slow and very expensive undertaking. Not until 1839, in

England, following the plans of Sir Rowland Hill, was the sending

of a letter made so inexpensive that anyone who could write could

afford to send what he had written, by mail; using the penny post.

CONDITIONS IN AMERICA

In America the development was perhaps even slower, as post

riders had to travel through dangerous routes, often beset by

hostile Indians; and the same conditions for two hundred years

after the discovery of the country threatened the stage coaches

and even the boats which were employed between different ports.

The rates, too, were very high, as was natural in view of the

difficulties involved. By the Act of Congress, 1792, single letters

required up to twenty-five cents postage, and double and triple

letters two and three times as much. And these charges were for

distances comparatively short, for there was as yet no transcontinental

mail. A "single" letter, too, simply meant a single

sheet of paper. Not until 1845 was there really substantial relief

from this condition. Then five cents was made the rate for a single

letter up to three hundred miles, and ten cents for a greater

distance. The postmasters' provisional stamps (1845) and the first

regular United States postage stamps (1847), whose centenary we

are now celebrating, belong in this era. Four years later the

final basic change was made, and the ordinary letter rate became

three cents.

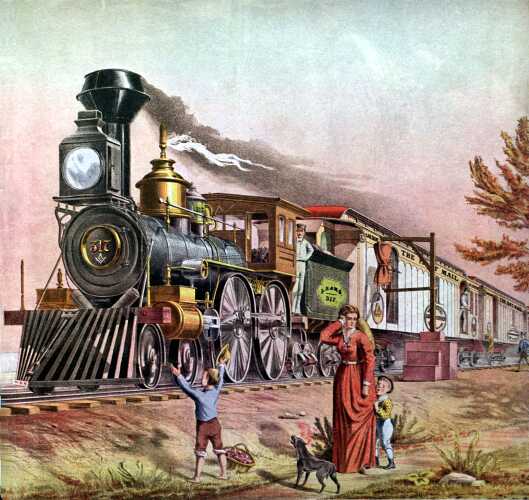

THE RAILROADS COME INTO BEING

Eighteen years before the United States Government issued its

first postage stamps, the first railroad train drawn by a locomotive

was put into operation by the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company,

and the next year, 1830, saw the first American-built engine draw

a train on the Baltimore & Ohio. This beginning, and the rapid

expansion of railroads in the United States, naturally encouraged

the use of the posts, and meant ever greater speed in the transportation

of the mails. In 1832 the Government allowed Slaymaker and Tomlins,

stage mail contractors, $400 extra per year for carrying the mail

from Philadelphia to Chester, Pennsylvania, by rail rather than

by coach. In 1782 the Government had declared a monopoly of the

postal service throughout the United States; in 1823 it extended

this monopoly to all navigable streams; and in 1838 all railroads,

for this purpose, were declared post-roads.

THE STAGE ROUTES ARE GRADUALLY ELIMINATED

Naturally the owners of the stage routes with mail-carrying

contracts did not readily yield their prerogatives to the railroads.

Shortly after the opening of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

in the summer of 1830, the locomotive "Tom Thumb," driven

by Peter Cooper, was distanced in a race with a certain powerful

gray horse. This naturally brought fame to the horse, and satisfaction

to his owners, Stockton and Stokes, who were the most important

owners of stage routes in their day, and of the contracts for

carrying the mail. Soon, however, the railroad began to carry

mail, first by arrangement with the regular mail contractors;

and within two or three years the contractors were asking the

Government to agree to their having the mail transported by the

railroad. Specifically, a contractor in February 1834 engaged

the Camden & Amboy Railroad Company to convey the mails for

him. As the railways grew, they gradually displaced the horse

as a means of mail conveyance, and there was much dispute between

the Department and certain railroad companies as to what should

be fair compensation for their services.

CONGRESS ACTS

On July 7th, 1838, the Act of Congress just referred to declared

that "each and every railroad, which now is or hereafter

may be made and completed, shall be a post route; and the Postmaster

General shall cause the mail to be transported thereon not paying

more than twenty-five per centum over and above what similar transportation

would cost in post coaches." Mail routes, which had of course

been established for the stage coach transportation, were now

made much more detailed and elaborate as the railways took up

the work. The management of the mail en route was held by "route

agents," so called.

THE ROUTE AGENTS AND THEIR WORK

The first route agent, a government official, was appointed

in 1837, probably on the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad. He was

a post-office employee, with many of the duties of a postmaster.

The first recorded cancellation referring to railroads is on a

pre-stamp letter dated November 7th, 1837. This cancellation is

RAILROAD, on a letter sent by way of the Mohawk & Hudson line,

running out of Albany, New York. Many of the mail routes had a

route agent from the early days. On July first, 1882, every type

of railroad service which required the presence of a post-office

employee on the railroad cars became a Railway Post-office; their

names were not, except accidentally, associated with the names

of the railroads over which they operated. These early railroad

postmarks, as distinguished from RPO postmarks, constitute a very

interesting chapter in United States postal history.

CAMPAIGN FOR PENNY POST IN THE UNITED STATES

In 1848, when the five and ten cent rates were in force in

the United States, an Association was formed in New York with

the avowed purpose of campaigning for a literal equivalent throughout

this country of Sir Rowland Hill's Penny Post. It was urged that

the basic rate for letters for any distance in the United States

be set at two cents, if prepaid (this was still optional) and

weighing under half an ounce; and that newspapers be charged at

the rate of one cent a sheet, while letters be delivered free

of charge in all large cities and towns. This association met

with effective opposition, and became particularly bitter against

the railroads. In view of present practice in the matter of mail-carrying

by the railroads, a brochure of this organization, printed in

1848, may prove especially interesting.

RAILROAD TRANSPORTATION—THE EVILS

"One of the most difficult points in the administration

of the post-office has been dealing with railroad corporations.

As these are bodies without souls, they can only be dealt with

on the footing of pecuniary interest. And as they are state institutions,

and local favorites, public opinion has been generally predisposed

to take sides with the railroad, and against the department. And

thus the railroads have been able to exact exorbitant allowances

for services which cost them next to nothing. Were the whole mails

of the country to be sent at once by a single railroad, what would

be the amount? The average number of letters mailed in a day is

142,857; which, at the average weight of one-third ounce, would

weigh 2,976 pounds. The average number of newspapers in a day

is 150,685, which, at the average weight of two ounces, would

give 18,834 pounds. The whole together make 21,815 pounds, equal

to 109 passengers, averaging, with their baggage, 200 pounds each.

These passengers would be carried by railroad 200 miles, from

Boston to Albany, for $545. The daily cost of railroad service

is $1,637, which shows that it is distance, not weight, that is

chiefly regarded. Or, in other words, that the weight of the mails

is of very little account to railroads. It is well known that

corporations regard the carriage of the mail as almost clear profit.

The whole daily mails of the United States could be carried by

the inland route from Boston to New Orleans, by the established

expresses, at their regular rates on parcels, for a little over

$3,000; while the whole daily expense of mail transportation is

$6,594. The expresses will carry from Boston to New York, for

$1.50, an amount of parcels which the Post-office would charge

$150 for carrying as letters, or $18.40 as newspapers and all

go by the same train, of course involving equal cost of transportation

to the company. The inference is unavoidable, that the government

is charged exorbitantly by these companies, from, the entire absence

of competition on almost every railroad route. While human nature

remains the same, it is to be expected that corporations will

take this advantage, unless some counteracting interest can be

brought to bear upon them as a restraint against extortion."

RAILROAD TRANSPORTATION—THE REMEDY

"Now, let the post-office present itself to the people

as a system of pure and unmingled beneficence, studying not how

it can get a little more money for a little less service, but

how it can render the greatest amount of accommodation with the

least expense to the public treasury, and it will at once become

the object of the public gratitude and warm affection; men will

study how to facilitate all its transactions, will be conscientiously

careful not to impose any needless trouble upon its servants,

and will generally watch for its interests as their own. Such

is the benign effect upon all the considerate portions of society

in England. Then the government will be fully sustained in insisting

that all railroads shall carry the mail for a compensation which

will be just a fair equivalent for the service performed, in reasonable

proportion to other services. And if the corporations are perverse

in throwing obstacles in the way, the people will expect that

such coercive measures should be employed as wisdom may prescribe,

to make these creatures of their power subservient to the public

good, and not to mere private aggrandizement."

CONCLUSION OF THE ARGUMENT

The brochure proceeds to state that the cost of mail transportation

in England is about five and a quarter pence per mile; in the

United States about twelve cents per mile. Again, "the average

weight of passengers with their baggage is set at 230 pounds.

This would be equal to the weight of 7,360 letters, at half an

ounce each, the postage on which at two cents would be $147.20,

irrespective of distance." Against this the passenger fare

from Boston to New York is stated to be $4.00, and the express

freight of an equal weight to be $1.50. While even to Liverpool

per Cunard steamers the passenger fare is $120, and the express

freight $7.20. The cost of transporting a letter from London to

Edinburgh has been ascertained to be one thirty-sixth of a penny.

THE RAILWAY MAIL SERVICE

Until the year 1864 the only connection between the railways

and the postal service was the fact that the mail pouches were

carried on trains—and a record kept of the quantity, the

distance, and the speed. Only occasionally is there evidence of

further activity on the part of the route agent. From the beginning

of the Civil War the great increase in mail due to that conflict

resulted in long delays in transmission and delivery; letters

had to be sent to a distributing office, sorted there, made into

wrapped packages with the name of their destination written on

each, and forwarded from that point. A story is told of a mail

pouch sent from Chicago to the Green Bay distributing office in

Wisconsin, about 1855, whence its contents were to be shipped

to points in the Upper Michigan peninsula. When it was opened

at Ontonagon a month later, a nest of mice, parents and offspring,

was found to have established itself in the pouch. This violation

on the part of the mice of the rules of the Post-office Department

impressed at least one post-office official with the need of a

change in the handling of the mail.

GEORGE B. ARMSTRONG

George Buchanan Armstrong, assistant postmaster at Chicago,

conceived the idea of having the pieces of mail sorted and distributed

in mail cars en route. Through the help of Schuyler Colfax, then

Speaker of the House, and A. N. Zevely, Third Assistant Postmaster

General, he was authorized to test his plan. He prevailed upon

the officers of the Chicago & Northwestern Railway to equip

some of their mail-cars for service as his "traveling post-office";

and the first run was made August 28th, 1864, from Chicago to

Clinton, Iowa. In 1867, as this idea proved itself, the Chicago

& Northwestern introduced post-office mail cars, especially

built from plans furnished by Armstrong. The great saving of time

resulting from this service was at once apparent, other roads,

first in the middle west and then in the east, adopted the plan,

and before the end of Grant's first term as president the practice

had become general. Mr. Armstrong had been put in charge of the

entire railway mail service of the country, as General Superintendent,

in 1869. In the Government Building in Chicago stands a bronze

bust erected to his memory in 1881. He died August 5th, 1871.

It may truly be said that today, because of the developments following

his work as a pioneer, a letter may even reach its destination

before a passenger setting out from the same place at the same

time.

AT THE END OF THE LAST CENTURY

A thumbnail picture of the mail service of railways, as it

existed in the latter part of the nineteenth century, is given

in the following account. It is not anti-railway. Every railway

was a postal route. But the basis of compensation, for one thing,

was unsatisfactory. Cost was directly dependent upon weight, speed

of trains, and condition of the property. The government, however,

calculated the rate for each "mail route" from the average

weight of the mails for that route. The whole matter transported

was weighed once each four years, for thirty consecutive working

days, and this formed the basis of compensation for the four years

following. The Government alone determined the price it would

pay the carrier; and if it saw fit, it might change the rate at

any time, and the railroad would have no redress. The rate was

sharply reduced as the volume increased, so that "the price

for transporting 5,000 pounds daily was only four times as much

as that for transporting 200 pounds." The Government alone

took all charge, through its own personnel, but at terminal points

the railroad had to transport all mail matter between the station

and the post-office at the same rate as that set for transportation

on the railroad itself; and at local stations it had to perform

the same service without compensation, unless the distance was

over eighty rods. The Government also imposed fines for delays

or failure to meet schedules as ordered. And in deciding who was

at fault the Government was sole arbiter. "The development

of the railway postal service is altogether due to the generosity

of the carrier. But the Government has rarely dealt fairly with

the railway companies." The railway mail service was recognized

as particularly hazardous; and for this reason it was contended

by many that insurance and pensions should be provided by the

Government for those who handled the mails on railroads, in exactly

the same manner as it provided for those who had been soldiers

in their country's defense.

TWENTIETH CENTURY CONDITIONS

Conditions in the twentieth century are greatly improved over

the state of affairs existing about 1900. In 1916 the "weight

basis" of pay for the railroads' services, which had stood

from 1836, was in part replaced by the "space basis,"

and in 1920 was entirely superseded by it. Space was obviously

the important factor, for by 1943 there were over 3,500 mail cars

required to convey the mails in the United States alone. In 1925

for New England, and in 1928 for the country as a whole, Government

adjustments in the rate paid the railroads were made upward, in

order to bring the remuneration more directly in line with the

cost involved.

By 1943, the railroads carried the mails a distance of 486,466,650

miles in a single year, and received therefor a compensation of

over one hundred and ten million dollars. In this same year the

clerks in the mail cars handled and redistributed over twenty

billion pieces of mail (roughly seven million pounds) thirteen

billion of these being letters. This was in addition to about

two hundred million miles of transportation performed by the airlines

and motor vehicles.

In 1945, the latest date for which statistics are available,

the Post-office Department spent about eleven percent of its income

for railway transportation of the mails, and about six and a half

percent more for the railway mail service. Some two hundred and

thirty million dollars was the amount expended in these two categories.

Today a railroad gets two mills, one fifth of a cent, for carrying

a letter across the continent. And the railroads carry ninety-two

percent of all the mail transported in the United States.

SPECIAL SERVICES BY THE RAILROADS

On special occasions recently the railways have provided special

service. In 1939, at the time of the visit of the King and Queen

of Great Britain, a special postal car was attached to their train

from the time it left the Canadian border, June seventh, to the

time it returned to Canada via Rouses Point three days later.

Thus the Post-office Department was enabled to handle over one

hundred thousand covers, with a special postmark to commemorate

the occasion.

Similarly, during the months of the World's Fair in New York,

in 1939 and 1940, a postal car, in charge of railway postal clerks,

was on exhibition on a railway siding. Visitors to the car averaged

5,215 a day, sets of commemorative stamps were sold there to the

average daily amount of over a hundred dollars, and the daily

deposit of mail was over 2,000 pieces.

THE CHESAPEAKE AND OHIO

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, a trunk line from the Atlantic

seaboard at Newport News, the world's largest ice-free harbor,

to Chicago and the West, has had no small part in the development

of the mail service. Its route was originally the Midland Trail,

surveyed by George Washington. He planned a great East-West network

of canals and post-roads, through what is now known as the Chessie

Corridor. In 1785 the James River Company was organized, and was

the original predecessor of the C & O, which now traverses

the States of Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana,

as far as Chicago. An example of the present volume of mail carried

on this line is a statement by the postmaster of Huntington, West

Virginia, (pop. 85,000), that in a single month in 1945 his office

cancelled a total of 1,942,339 pieces of mail.

RAILWAY POSTAL CAR # 106

A further elaboration of present conditions in the Railway

Post-office system is provided by the description of a typical

mail route on the Pere Marquette Railway, a connection of the

C & O. R.P.O. car # 106 is attached to train #7, on the Grand

Rapids-Chicago run. This run is part of the Ninth Division of

R.M.S. (there are fifteen in all). On each run the clerks in #

106 distribute letters for Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin,

Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Chicago, including Mixed States

mail and airmail. Newspaper distribution includes all these States,

Missouri, South Dakota, (not Nebraska) and Mixed States. The average

distribution each night consists of seventy-six pouches, containing

approximately 1065 working letter packages, and 107 sacks of paper

mail. A full sized R.P.O. car is sixty feet long, provides 744

letter-case separations, 210 paper and pouch rack separations,

and about thirteen and a half feet available storage space.

"Apartment cars" are 15- or 30-foot ends of baggage

cars, especially fitted. "Storage cars" are those in

which the mail is not "worked." On this train the Government

allows eighteen to sixty feet of storage space extra. As railroads

are paid on the basis of storage space, very accurate records

must be kept. At non-stop stations on this route pouches are thrown

off, or picked up by a "catch-arm." These pouches are

"worked" immediately. Sacks are used for all except

first class mail; for first class mail, locked pouches. And all

this elaborate and detailed procedure sprang from the beginnings

made by George B. Armstrong in 1864.

OWNIE

A fitting conclusion to this story of the railroads and the

mails may be the history of a famous dog, the only one ever to

be adopted by the Post-office Department. "Ownie" spent

his life in mail cars; beginning in 1888 on the run from Albany

to New York City, he was a pet of the mail clerks, who kept attaching

tags to his collar till he had 1017. He visited Canada and Alaska,

and in 1895 took a trip to Japan, where he was decorated with

a medal by the emperor. He went on around the world, and got back

to Tacoma, Washington, after 132 days. Unhappily he met an ignominous

end, for he was shot on the orders of a postmaster in Cleveland,

Ohio, who had never heard of him. The postmaster nearly paid for

his ignorance with his own life. During his vacations Ownie had

travelled one hundred and forty-three thousand miles. And for

many a railway mail clerk the monotony of his labors must have

been broken by the presence of this dog, who appreciated the opportunities

afforded by the Railway Mail Service.

GILMAN KNOWLTON.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|