|

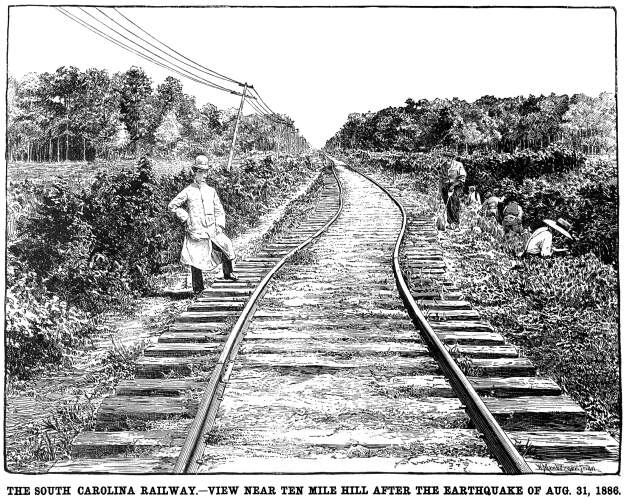

Effect of the Earthquake on the

South Carolina Railroad

Scientific American—November 20,

1886

Never before in this country has there been, and if it is to

be hoped never again will there be, opportunity to present such

a picture of the effect of "the bottom dropping out of everything"

as that which we present in this issue in our engraving (an exact

reproduction of a photograph) of what was left of what had before

been a tangent on the South Carolina Railway, near the point where

a bad accident and worse scare occurred on the night of the earthquake

of August 31, and where (we presume) the dislocation was exceptionally

severe. It hardly seems possible that the sharp curve in the foreground

can be wholly due to a permanent dislocation of the surface, but

we are informed that it was, as also the quick drop in grade in

the "middle distance." The photograph gives obscure

evidence of still further dislocations in the background, which

has been rather softened than obscured in the engraving.

The Charleston & Savannah road is said to have suffered

on the whole even more severely than the South Carolina or the

Northeastern as respects dislocation, although all the serious

wrecks occurred on the other lines. Accounts of three of those

wrecks, including the one near the point illustrated, were given

in our issue of September 10, as also a description of the accompanying

" quakes." In connection with this engraving, the nature

of the catastrophe, and the fact that the description is probably

not exaggerated, can be better appreciated, and we therefore reproduce

the substance of it:

"Near Ten Mile Hill a fatal accident occurred on Tuesday

night. The down Columbia train (South Carolina Railroad) jumped

the track under the unseen influence of the shock that dismantled

the road. It is said that the earth suddenly gave way, and that

the engine first plunged down the temporary declivity. It was

then raised on the top of the succeeding terrestrial undulation,

and, having reached the top of the wave, a sudden swerving of

the force to the right and left hurled the ill-fated train down

the embankment.

"How it was done was plainly indicated. In many places

along the track of the South Carolina and the Northeastern railroads;

and for spaces of several hundred yards in width, the dreadful

energy of the earthquake was expended in two particular ways.

First, there were intervals of a hundred yards and more in which

the track had the appearance of having been alternately raised

and depressed,

like a line of waves frozen in their last position. The second

indication was where the force had oscillated from east to west,

bending the rails in reverse curves, most of them taking the shape

of a single, and others a double letter S placed longitudinally.

These latter accidents occurred almost invariably at trestles

and culverts. There were no less than five of them between the

Seven Mile Junction and Jedburg. In other places the track had

the appearance of being kinked for miles, but always in these

cases in the direction of the rails. and depressed,

like a line of waves frozen in their last position. The second

indication was where the force had oscillated from east to west,

bending the rails in reverse curves, most of them taking the shape

of a single, and others a double letter S placed longitudinally.

These latter accidents occurred almost invariably at trestles

and culverts. There were no less than five of them between the

Seven Mile Junction and Jedburg. In other places the track had

the appearance of being kinked for miles, but always in these

cases in the direction of the rails.

"The train at the time of the earthquake was running along

at the usual speed, and when about a mile south of Jedburg it

encountered a terrible experience. It was freighted with hundreds

of pleasure seekers returning from the mountains. They were all

gay and happy, laughing and talking, when all of a sudden, in

the language of one of them, the train appeared to have left the

track, and was going up, up, up into the air. This was the rising

wave. Suddenly it descended, and as it rapidly fell it was flung

first violently over at the east, the side of the car apparently

leaning over at less than an angle of 45 degrees. Then there was

a reflex action, and the train righted and was hurled, with a

roar as of a charge of artillery, over to the west, and finally

subsided on the track and took a plunge downward—evidently

the descending wave. The engineer put down the brakes tight, but

so great was the original and added momentum that the train kept

right ahead. It is said on trustworthy authority that the train

actually galloped along the track, the front and rear trucks of

the coaches rising and falling alternately. The utmost confusion

prevailed, women and children shrieked with dismay, and the bravest

hearts quailed in momentary expectation of a more terrible catastrophe.

The train was then taken back in the direction of Jedburg; and

on the way back the work of the earthquake was terribly plain.

The train had actually passed over one of those serpentine curves

already described."

Two other accidents of the same general nature were likewise

described in the same issue. The only pleasant feature in these

occurrences, to a railroad man, is that at least it can be said

of them, with literal and indisputable truth, that "no one

was to blame." —Railroad Gazette.

Mother

Nature | Contents Page

|