|

MUNSEY'S MAGAZINE.

VOL. XXIV. FEBRUARY, 1901. No. 5.

The Marvels of Mountain Railroading.

BY GEORGE L. FOWLER.

THE TRIUMPHS OF SKILL AND DARING ACHIEVED BY THE RAILROAD

ENGINEERS WHO HAVE CONQUERED THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS, THE ALPS, AND

THE ANDES.

IT has

long been an axiom among engineers that no task of construction

is beyond their skill if only sufficient money be provided. Nothing

illustrates this more forcefully and more practically IT has

long been an axiom among engineers that no task of construction

is beyond their skill if only sufficient money be provided. Nothing

illustrates this more forcefully and more practically  than the building of railroads that traverse

mountains. Over and over again it has been proven that there are

no natural obstacles that cannot be overcome. The traveler who

shudders when be looks down hundreds of feet from a car window,

or scowls when he is rushed into a tunnel, seldom understands

at what terrific cost his comfort was bought. Neither does he

realize the dangers which actually surround him, and the small

things upon which his life depends. If he did, he would probably

be panic stricken. than the building of railroads that traverse

mountains. Over and over again it has been proven that there are

no natural obstacles that cannot be overcome. The traveler who

shudders when be looks down hundreds of feet from a car window,

or scowls when he is rushed into a tunnel, seldom understands

at what terrific cost his comfort was bought. Neither does he

realize the dangers which actually surround him, and the small

things upon which his life depends. If he did, he would probably

be panic stricken.

The safe running of a train over an ordinary division requires

an almost infinite amount of care and vigilance, not only In the

present, but in the past as well, beginning from the time when

the engineers were surveying and locating the line. The choice

of a route may mean the future courting or avoidance of a disaster.

There must be knowledge of the geological formation of the ground

over which the track is to he laid, and its risk of exposure to

freshets, subsidences, landslides, avalanches, and snow blockades.

Past performances must be the data upon which future good or bad

behavior must be predicated, and it is upon the intimacy of his

knowledge with that past that the work of the engineer is to be

judged.

In a country that has been peopled for generations, the work

of the engineer is greatly facilitated: but where he must strike

out into new territory—where he must draw conclusions from

such knowledge as he can extort from nature itself or can gather

front the hazy, rambling talk of the savage or the mountaineer—here

his ability, perseverance, and judgment must be of the highest

order.

RAILROAD PIONEERS IN THE WEST.

In few countries

has the railroad builder been asked to overcome such difficulties

as in the mountains of the Western States and Canada. Crossing

the border between civilization and savagery he has pushed his

lines in advance of the frontier settlements, fighting with the

wildest of elements, beasts, and men for every foot. He has followed

mountain torrents to their sources, climbed peaks where the white

man had never stood before; explored canyons which the Indians

said no man could enter and come out alive; dangled by ropes over

precipices and painted his marks on the living rock, because there

was no crevice in which to drive a stake. In one case, at least,

he has taken his railroad over a mountain pass in advance even

of the Indian's trail. All these things have been done far from

any base of supplies. He has been cut off from civilization for

months at a time and has lived on the rifles of his hunters, while

searching for the best way to reach his destination, and guarding

constantly against a treacherous and malignant foe. Only by such

toil and suffering has he driven his stakes to mark the route

over which the thoughtless occupant of the parlor car shall afterwards

roll in comfort and luxury. In few countries

has the railroad builder been asked to overcome such difficulties

as in the mountains of the Western States and Canada. Crossing

the border between civilization and savagery he has pushed his

lines in advance of the frontier settlements, fighting with the

wildest of elements, beasts, and men for every foot. He has followed

mountain torrents to their sources, climbed peaks where the white

man had never stood before; explored canyons which the Indians

said no man could enter and come out alive; dangled by ropes over

precipices and painted his marks on the living rock, because there

was no crevice in which to drive a stake. In one case, at least,

he has taken his railroad over a mountain pass in advance even

of the Indian's trail. All these things have been done far from

any base of supplies. He has been cut off from civilization for

months at a time and has lived on the rifles of his hunters, while

searching for the best way to reach his destination, and guarding

constantly against a treacherous and malignant foe. Only by such

toil and suffering has he driven his stakes to mark the route

over which the thoughtless occupant of the parlor car shall afterwards

roll in comfort and luxury.

The early railroad work in the Rocky Mountains stands unique

in the history of the science, in that it was the advance guard

of civilization, and was called upon to solve entirely new problems

and work out its own salvation in its own way, with little or

no  suggestive

help from what bad gone before. Given sufficient capital, a railroad

between almost any two points becomes a possibility; but even

when the road has been built over the most careful of surveys,

its operation may present difficulties as great as those encountered

in the work of exploration and construction. This is especially

true of the roads in the higher altitudes, where snow falls during

the greater part of the year, and where the winter accumulation

is so great as to defy the management to maintain a clear-track,

even avalanches and "flurries" were unknown. suggestive

help from what bad gone before. Given sufficient capital, a railroad

between almost any two points becomes a possibility; but even

when the road has been built over the most careful of surveys,

its operation may present difficulties as great as those encountered

in the work of exploration and construction. This is especially

true of the roads in the higher altitudes, where snow falls during

the greater part of the year, and where the winter accumulation

is so great as to defy the management to maintain a clear-track,

even avalanches and "flurries" were unknown.

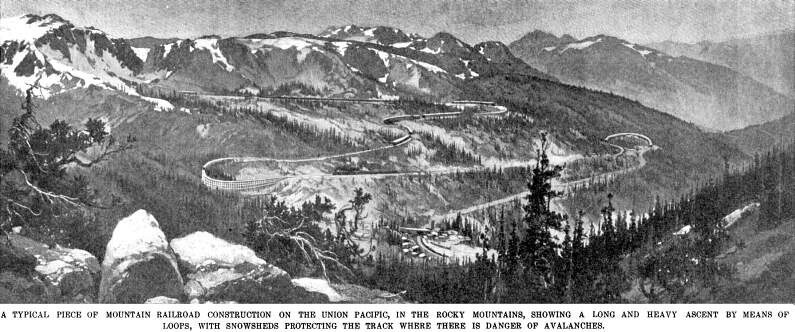

FIGHTING SNOW IN THE ROCKIES

As a result of these conditions, all the Rocky Mountain roads

are provided with snowsheds. These are not mere coverings to protect

the road from a gentle fall of snow, but substantial structures,

that would compare in strength with many an old fortification

intended to withstand the assaults of artillery. They may be designed

merely to carry a dead weight of snow, or to withstand the terrific

action of avalanches upon one or both sides. When the avalanche

is to be guarded against, the mountain side of the shed is built

of a cribwork of timbers twelve inches square, and filled in at

the back with solid rock, designed to carry the snow over the

roof of the shed without permitting the moving mass to strike

heavily against it. The outer edge of the roof is supported by

heavy timbers. Such sheds cost from forty to seventy dollars a

foot, according to circumstances.

Long sheds are objectionable, because their cost is great,

and because gases from the locomotive gather in them. Therefore

the sheds are usually built in sections, made as short as possible.

The openings are protected by "glance works," or "split

fences," intended to divert the course of the sliding mass

of snow, ice, and rocks. These are V shaped fences, the apex pointing

up the mountainside, which throw the descending debris to the

right or left so that it will pass over the sheds. Sometimes one

of these barricades is insufficient, and others are built farther

up the slope. They are of cribwork or piles, strengthened by a

filling of rock work.

Where the Canadian Pacific passes the crest of the Rocky Mountains,

there are about six miles of snowsheds, containing twenty five

million feet of sawed timber, and one million, one hundred and

forty thousand lineal feet of round timber. The snowfall in that

region is at times very great. In the winter of 1886-87 it was

thirty five feet in the Selkirk range; eight and a half feet fell

in six days. At that time the snowsheds were buried under fifty

feet of snow, so compacted that it weighed thirty pounds to the

cubic foot.

If the railroads

had to contend only with the snow as it fell, they would seldom

have much trouble. But it may be melted by the Chinook winds and

winter rains, and then there may come a sudden fall of the temperature

to thirty degrees below zero, making a compact mass of snow and

ice that only blasting can remove. More dangerous and harder to

control is the "awful avalanche," which may come down

the mountainside so gently and so quietly as to cause no pressure,

no strain, no disaster, or it may start far up the slope, and,

gathering force as it descends, hurl down a huge mass of snow,

ice, rocks, and uprooted trees weighing a quarter of a million

tons. It moves with the roar of a volcano and the speed of a cyclone,

shaking the earth in its progress and sweeping everything before

it, a spectacle of awful magnificence when viewed from a safe

distance. In its mad rush, the avalanche makes a "flurry,"

a local cyclone, which sometimes extends for a distance of a hundred

yards outside its path. This fierce blast of air uproots or snaps

off trees that rise a hundred and fifty feet from the ground. If the railroads

had to contend only with the snow as it fell, they would seldom

have much trouble. But it may be melted by the Chinook winds and

winter rains, and then there may come a sudden fall of the temperature

to thirty degrees below zero, making a compact mass of snow and

ice that only blasting can remove. More dangerous and harder to

control is the "awful avalanche," which may come down

the mountainside so gently and so quietly as to cause no pressure,

no strain, no disaster, or it may start far up the slope, and,

gathering force as it descends, hurl down a huge mass of snow,

ice, rocks, and uprooted trees weighing a quarter of a million

tons. It moves with the roar of a volcano and the speed of a cyclone,

shaking the earth in its progress and sweeping everything before

it, a spectacle of awful magnificence when viewed from a safe

distance. In its mad rush, the avalanche makes a "flurry,"

a local cyclone, which sometimes extends for a distance of a hundred

yards outside its path. This fierce blast of air uproots or snaps

off trees that rise a hundred and fifty feet from the ground.

So rapid is the movement of the avalanche that sometimes, when

the railroad sheds have been broken in and filled with debris,

large vacant spaces have been found in the mass, showing where

air has been caught and imprisoned by the falling snow. With such

natural terrors to contend with, it was a wise provision on the

part of the railroad authorities to provide each dining car on

its through trains with an emergency box, to be opened only as

a last resort, and to store food in caches along the line at intervals

of ten or twelve miles, in imitation of the hunters of the Hudson

Bay Company.

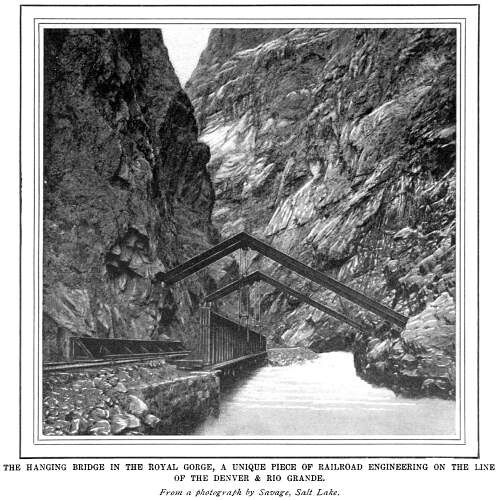

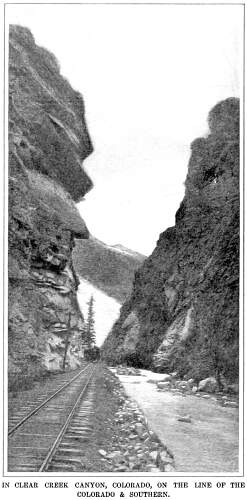

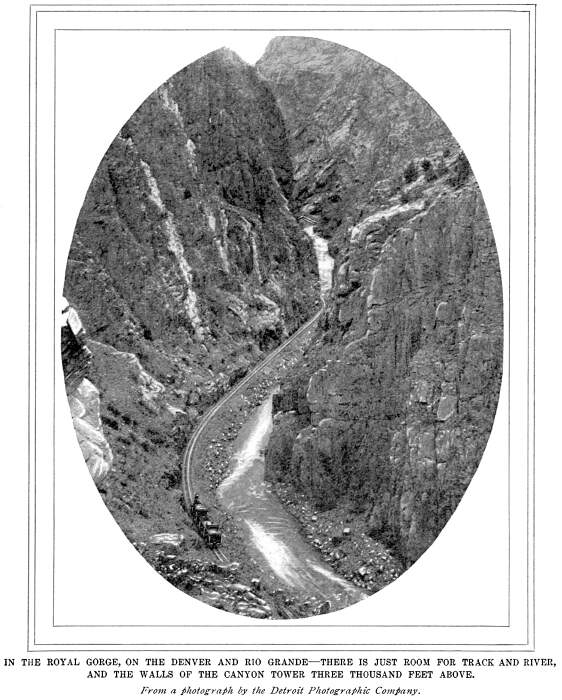

IN THE WESTERN CANYONS.

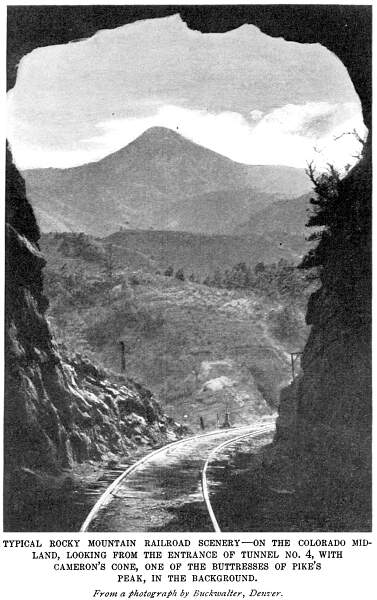

But snowsheds

are not the only interesting engineering features of the Rocky

Mountain roads. We find tracks running on shelves along the faces

of unscalable cliffs; they follow the windings of deep canyons;

they skirt great hills, and everywhere the work is one of might

and power. There is more romance in the building of these mountain

railroads than in the tales of chivalry; there are more adventurous

experiences and hairbreadth escapes than the inventive minds of

story writers ever conceived. There are a devotion, a pluck, and

an indomitable energy coupled with engineering genius That make

the deeds of the old knights seem puny and trivial. Take the story

of the Royal Gorge, where there is room but for one road, where

it was a matter of life and death to secure the right of way and

the surveyor's transit was ever guarded by the rifle. This was

the only route from Canyon City to Leadville, and a right royal

route it is. Here the Arkansas River emerges from the rocky fastnesses

in its wild plunge from the mountains to the plains, after a twelve

miles' course between cliffs rising three thousand feet in the

sheer, and with barely room between them for the tumbling waters

of the river. Through this wild canyon of mica, green serpentine,

and red sandstone the railroad edges its way up and up, disputing

with the water for every foot of the path, until, at last, at

the hanging Bridge, it leaves the whole width of the gorge to

the water, and crosses the stream on a plate girder bridge, one

side of which is suspended from a truss that has a footing on

either side of the lofty canyon walls. But snowsheds

are not the only interesting engineering features of the Rocky

Mountain roads. We find tracks running on shelves along the faces

of unscalable cliffs; they follow the windings of deep canyons;

they skirt great hills, and everywhere the work is one of might

and power. There is more romance in the building of these mountain

railroads than in the tales of chivalry; there are more adventurous

experiences and hairbreadth escapes than the inventive minds of

story writers ever conceived. There are a devotion, a pluck, and

an indomitable energy coupled with engineering genius That make

the deeds of the old knights seem puny and trivial. Take the story

of the Royal Gorge, where there is room but for one road, where

it was a matter of life and death to secure the right of way and

the surveyor's transit was ever guarded by the rifle. This was

the only route from Canyon City to Leadville, and a right royal

route it is. Here the Arkansas River emerges from the rocky fastnesses

in its wild plunge from the mountains to the plains, after a twelve

miles' course between cliffs rising three thousand feet in the

sheer, and with barely room between them for the tumbling waters

of the river. Through this wild canyon of mica, green serpentine,

and red sandstone the railroad edges its way up and up, disputing

with the water for every foot of the path, until, at last, at

the hanging Bridge, it leaves the whole width of the gorge to

the water, and crosses the stream on a plate girder bridge, one

side of which is suspended from a truss that has a footing on

either side of the lofty canyon walls.

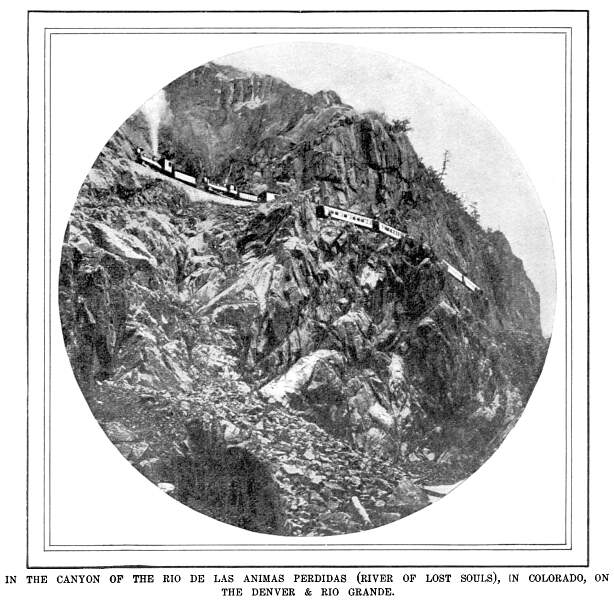

Again, in the canyon of the Rio de las Animas Perdidas (the

River of Lost Souls) the Denver & Rio Grande, after following

the bed of the river for about fifteen miles from Silverton, plunges

into the gorge. At first, the road is but a few feet above the

level of the stream; then the grades become steeper, the curves

sharper, the surroundings wilder, until, almost before the passenger

is aware, the train is running along a shelf cut in the face of

the cliff, with the river a ribbon of foam and mist hundreds of

feet below.

A photograph gives only a faint idea of the engineering difficulties

encountered in the construction of a line where there was hardly

a chance for the setting of the tripod of the transit. Indeed,

in some of the Colorado canyons the location was determined by

triangulation, because of the absolute inaccessibilitv of the

route, which was to run where no living being but the birds of

the air had been before. Such work, like many other great enterprises,

would have been commercially impossible before the discovery of

the nitroglycerin compounds. The successful use of nitroglycerin

in the work of the Hoosac tunnel led to the later production of

dynamite, a safer compound to handle; and this, in turn, has given

way, to a great extent, to the glycerin gelatine, which will endure

a still greater amount of rough treatment without exploding.

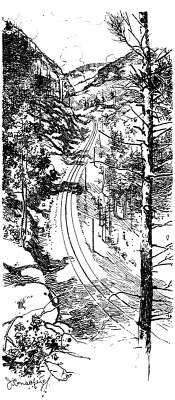

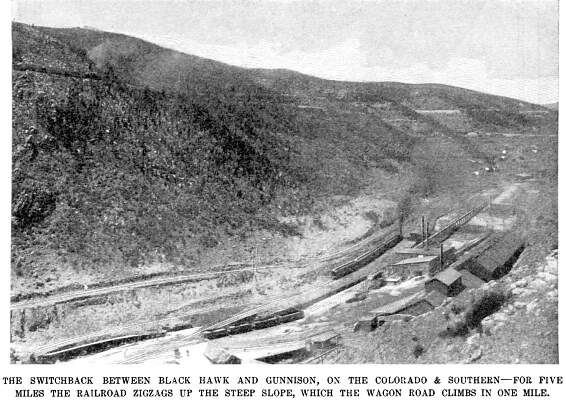

THE LOOP AND THE SWITCHBACK.

Interesting

as the canyon work is from an engineering standpoint, laborious

as the task of blasting may have been, and picturesque, as the

results of these cuttings undoubtedly are, as the photographs

show, they constitute but a small part of the work of the railroad

builder. Where a mountain has to be climbed, and the entering

valley is narrow and steep, and where the side valleys cannot

be used to lengthen the line and ease the grades, the engineer

must resort to such devices as the switchback and the loop. The

former is a simple expedient for zigzagging up a mountainside.

The track runs up the valley until the mountain blocks the way;

it then starts back in the opposite direction, and climbs higher

until it is again stopped, perhaps by a precipitous slope, perhaps

by the ending of the spur upon which it rests. Again its direction

is reversed, and this method is continued until a point is reached

where it is high enough to reach the crest of the divide, so that

it can go its way without let or hindrance. Interesting

as the canyon work is from an engineering standpoint, laborious

as the task of blasting may have been, and picturesque, as the

results of these cuttings undoubtedly are, as the photographs

show, they constitute but a small part of the work of the railroad

builder. Where a mountain has to be climbed, and the entering

valley is narrow and steep, and where the side valleys cannot

be used to lengthen the line and ease the grades, the engineer

must resort to such devices as the switchback and the loop. The

former is a simple expedient for zigzagging up a mountainside.

The track runs up the valley until the mountain blocks the way;

it then starts back in the opposite direction, and climbs higher

until it is again stopped, perhaps by a precipitous slope, perhaps

by the ending of the spur upon which it rests. Again its direction

is reversed, and this method is continued until a point is reached

where it is high enough to reach the crest of the divide, so that

it can go its way without let or hindrance.

The loop requires more room than switchback, and is used in climbing

where the valley is broader.

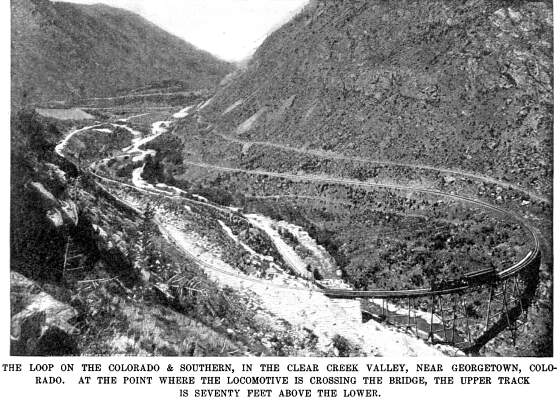

Probably the best known loop in the West is that of the Colorado

& Southern Railway, near Georgetown. Before reaching this

point, the road doubles back on itself twice, crossing Clear Creek

on each turn. Then it passes on to the loop, where it turns, crosses

the creek twice more, and passes beneath itself, with a distance

of seventy five feet between the upper and the lower line of rails,

running nearly four miles to secure an advance of two. This section

has an average grade of one hundred and sixty feet to the mile,

with a maximum of one hundred and ninety.

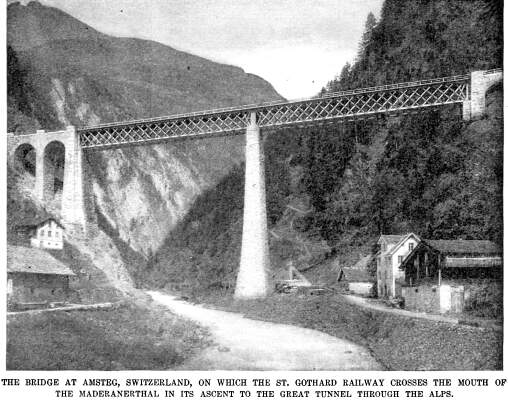

Sometimes the engineer is confronted with alternative courses.

He may be able to make a long detour, by which he can pass along

the side and across the head of a valley in order to reach the

opposite slope; or he can build a viaduct straight across as the

bird would fly. It then becomes a matter of cold blooded calculation

as to which would be the better investment. The viaduct, of course,

will cost more to build, but it may shorten the line by several

miles, and every train that crosses it will save time and money.

Careful estimates of the first cost of each plan are made, and

of the probable expense of operation and maintenance in view of

the traffic that may be expected. If the viaduct can show a saving

in operating expenses more than sufficient to pay interest on

its added first cost, the matter is settled, and the structure

is erected.

Thus the railroads

have been led over untrodden mountain passes, and through canyons

that for centuries had echoed only to the roar of cataracts and

rapids, but whose rocks now reverberate to the rumble of the fast

express. They have threaded valleys by the eagle's route, and

plunged through the granite of the everlasting hills by tunnels

that are but pin pricks in their rugged sides. Thus the railroads

have been led over untrodden mountain passes, and through canyons

that for centuries had echoed only to the roar of cataracts and

rapids, but whose rocks now reverberate to the rumble of the fast

express. They have threaded valleys by the eagle's route, and

plunged through the granite of the everlasting hills by tunnels

that are but pin pricks in their rugged sides.

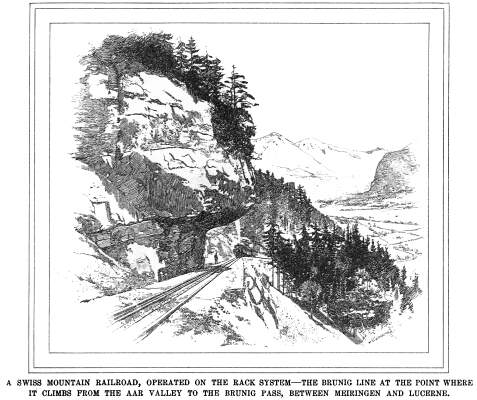

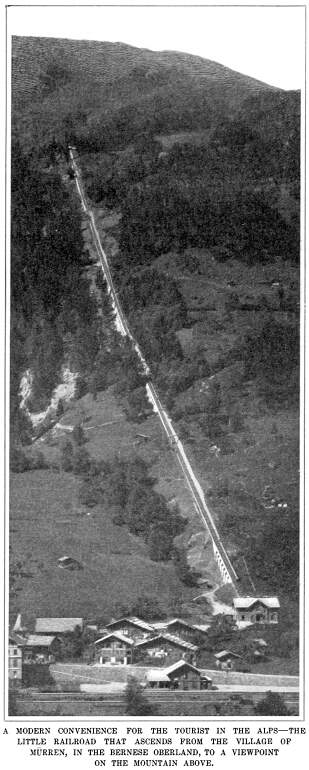

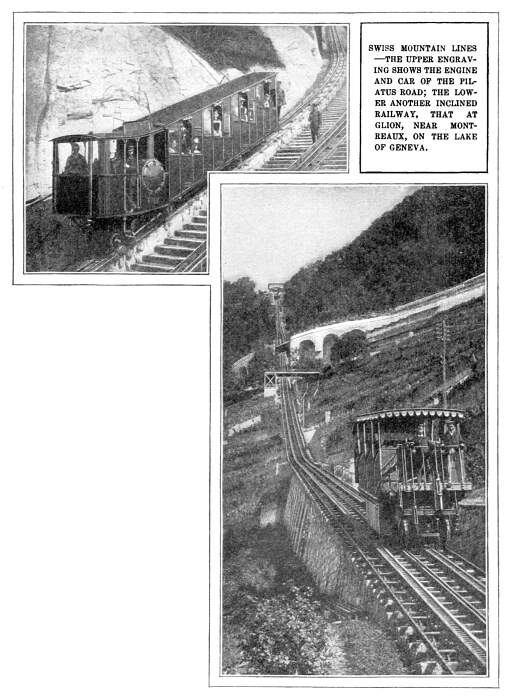

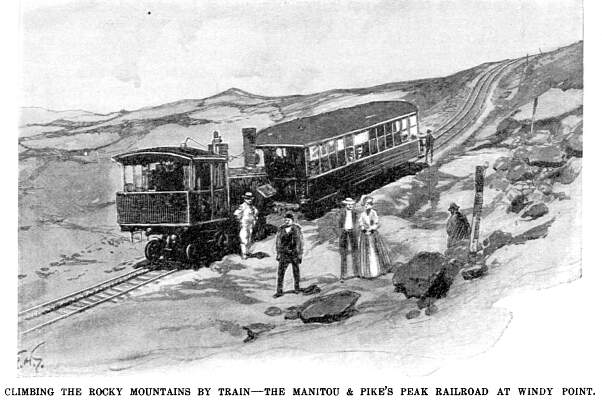

And when these things have been done still bolder schemes are

accomplished. A great peak is climbed by grades on which no smooth

faced wheel could roll, and the rack is used to hold and force

the train ahead. The rack system was first planned by a German

engineer for the Rigi, the mountain familiar to all tourists who

visit Lucerne; but the Swiss project was delayed, and before any

of the proposed road was constructed, a line of the same type

was built and put into operation on Mount Washington, in New Hampshire.

Some years later, a similar road reached the still loftier summit

of Pike's Peak, making the climb of that Western giant a mere

holiday trip, to be taken with the same blasé indifference

as the journey across the continent or the ocean.

THE HIGHEST RAILROAD IN THE WORLD.

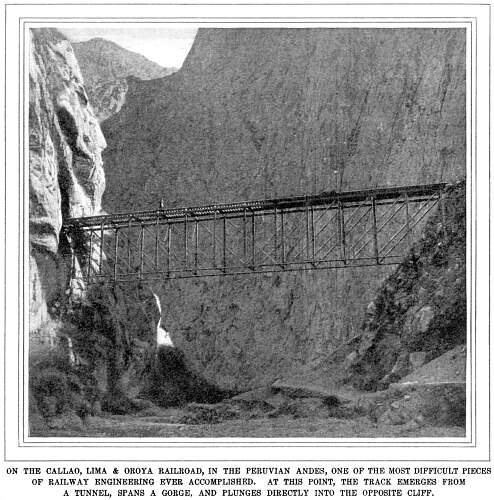

Our mountain

roads are great in the difficulties that they have surmounted,

and the energy with which they have been pushed to remote fastnesses

where nature seemed unconquerable. But wherever civilization has

settled, and wherever the miner has gone, there the railroad has

followed. In South America, especially among the Peruvian Andes,

mountain railroading has many examples of fine engineering to

show. In fact, there are places where the work done is unprecedented

in the history of the profession. The Callao, Lima & Oroya

Railroad famed throughout the world. Starting from the Pacific

Ocean, it follows the broad valley of the Rimac up past Lima to

Chosica, where the converging spurs of the Cordilleras crowd it

to a width of a thousand yards. Thence, in the tortuous defiles

of the Rimac the road climbs with a four percent grade, and over

curves of three hundred and fifty feet radius; it crosses and

recrosses The Rio Seco and spans a deep mountain gorge on the

famous Verrugas viaduct—a structure which, at a distance,

appears far too delicate for practical railroad work, but which

shows no appreciable deflection under the heaviest locomotives

on the road. Still up and up the track climbs, with detour after

detour, until, near Surco, there are three tunnels directly over

one another. But the heights to be scaled still reach on and on

until the Rimac gorge is crossed; thence we pass up a zigzag to

tunnel No. 14. Here the laying out of the line presented stupendous

difficulties and dangers. The men were lowered over the cliffs

from bench to bench cut from the naked faces of the rock, until

the levels were reached. Our mountain

roads are great in the difficulties that they have surmounted,

and the energy with which they have been pushed to remote fastnesses

where nature seemed unconquerable. But wherever civilization has

settled, and wherever the miner has gone, there the railroad has

followed. In South America, especially among the Peruvian Andes,

mountain railroading has many examples of fine engineering to

show. In fact, there are places where the work done is unprecedented

in the history of the profession. The Callao, Lima & Oroya

Railroad famed throughout the world. Starting from the Pacific

Ocean, it follows the broad valley of the Rimac up past Lima to

Chosica, where the converging spurs of the Cordilleras crowd it

to a width of a thousand yards. Thence, in the tortuous defiles

of the Rimac the road climbs with a four percent grade, and over

curves of three hundred and fifty feet radius; it crosses and

recrosses The Rio Seco and spans a deep mountain gorge on the

famous Verrugas viaduct—a structure which, at a distance,

appears far too delicate for practical railroad work, but which

shows no appreciable deflection under the heaviest locomotives

on the road. Still up and up the track climbs, with detour after

detour, until, near Surco, there are three tunnels directly over

one another. But the heights to be scaled still reach on and on

until the Rimac gorge is crossed; thence we pass up a zigzag to

tunnel No. 14. Here the laying out of the line presented stupendous

difficulties and dangers. The men were lowered over the cliffs

from bench to bench cut from the naked faces of the rock, until

the levels were reached.

The engineers were swung across the gorges on wire ropes stretching

from side to side. In one run of fifteen miles, there are twenty

two tunnels. At another point five parallel lines, hundreds of

feet above one another, are visible from any point in the valley,

three on one side and two on the other, while the greatest horizontal

distance between any two of them is fewer than five hundred feet.

Still it is up, up, to the head of the Rimac, which is inclosed

by unscalable cliffs, to overcome which seven tunnels had to be

constructed. At last, the road found itself amid a desolation

of snow and ice just below the dividing crest of the Andes. One

more boring, and then the Galera tunnel, 3,847 feet long and 15,645

feet above the sea, leads to the comparatively easy stretch down

to Oroya, the inland terminus.

Such, then, is a brief review of what the quiet man with the

transit has done to annihilate space and time; to rob mountain

climbing of its fatigues and dangers; to roll a panorama of beauty

and grandeur and sublimity before the eyes of those who would

otherwise never see it. He sets his goal wherever man desires

to go, and with courage, patience, and indomitable energy, amid

toil and hardship, he has marked out and built the road over which

his fellows may follow him in ease and luxury.

Mountain Railroading

| Contents Page

|