A LITTLE JOURNEY THROUGH THE AIR

St. Nicholas Magazine—1902

By KATHARINE MORGAN CROOKS.

WHEN I was small I often heard my elders tell what a great

invention a railway with wooden tracks, on which cars were drawn

by horses, had seemed to them when they were young. Nowadays we

are so used to the wonders of mechanics that the most extraordinary

methods of journeying appear as matters of course to us. Those

of you who have been in London have probably gone from one part

to another on the "Tuppenny Tube," the electric railway

deep in the earth, which winds its way like a long snake beneath

London. It is built with two single-track tunnels; each tunnel,

when you peer into it from an underground station, looks like

a big tube, and is not much higher or wider than the train. From

its shape and the fare, which is twopence (familiarly "tuppence"),

comes the nickname Tuppenny Tube.

Many of you have looked down

into the deep cuts in New York where men are digging and blasting

for a railway under the city; and most of you are familiar with

railways which, instead of burrowing in the ground, go on supports

through the air. A railway through the air is now a prosaic, every-day

affair. But there is one form of elevated-railway travel to which

we have not yet accustomed ourselves and which does seem odd.

This is an elevated railway where the car, instead of running

on the track, hangs from it. I took a little trip one day last

summer on the only railway of this kind in the world. Many of you have looked down

into the deep cuts in New York where men are digging and blasting

for a railway under the city; and most of you are familiar with

railways which, instead of burrowing in the ground, go on supports

through the air. A railway through the air is now a prosaic, every-day

affair. But there is one form of elevated-railway travel to which

we have not yet accustomed ourselves and which does seem odd.

This is an elevated railway where the car, instead of running

on the track, hangs from it. I took a little trip one day last

summer on the only railway of this kind in the world.

There flows in Germany, not far from the Rhine, a narrow winding

river called the Wupper. On this river, about twenty-seven miles

from the old city of Cologne, are two busy towns, Elberfeld and

Barmen. About where Elberfeld ends Barmen begins, so that together

they have a length of from six to eight miles. The factories and

houses of both line the two sides of the little river, fill the

narrow valley, and climb the hills which begin close beside the

river's banks. I took a walk in Barmen up one of these hilly streets,

and met an electric street car on its way down. The car ran on

a cog wheel railway, so you may imagine how steep the road was.

Although the odd kind of elevated railway of which we have spoken

is called the Elberfeld - Barmen Suspension Railway, the Barmen

end was not all finished at that time. It was, therefore, in Elberfeld

that I mounted the steps to a station not quite fifteen feet above-ground,

and paid five cents for a first-class trip to the end of the route.

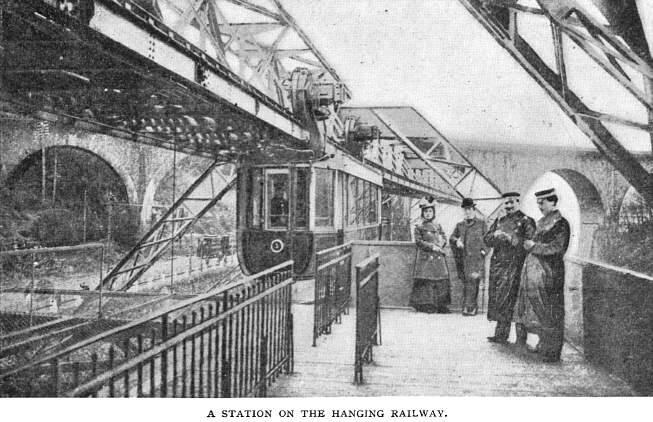

In the station, as you may see by the picture, a stout iron

netting is stretched for security between the two platforms, and

apparently there are tracks. In reality what one sees are supports

on which a car rests as the passengers get in and out, to prevent

its tipping. Each car runs alone, like a street-car, and is much

like a streetcar in appearance. The ends, however, instead of

being square, taper slightly, something like a kite, and there

is no open platform. Perhaps you would be interested to know something

more of these cars. With all its belongings a car weighs about

twelve tons; it is about thirty-eight feet long, over eight feet

high, and nearly seven feet wide, is divided by a glass door into

two compartments for first and second class passengers, and can

seat fifty persons. The trucks for the wheels—and this is

the curious part—are above the car, as you see, instead of

below. There are two of them, one to the front and one to the

back of the car; each has two wheels, one behind the other, so

that the car seems to hang from the top edge of one side. The

electricity is supplied to a motor for each truck by means of

a contact-rail running beside the rail on which the wheels rest.

When the railway is finished a car will run the whole route of

eight and a quarter miles, including stops at many stations, in

twenty-five minutes.

Now that we understand something

about it, we enter by the door at the side of the car, first passing

through the little gangway from the platform. The door is locked

after us, and without noise or jar the car starts. The windows

are large, and there is a glass door at each end besides those

on the side of entry; a platform to the front, on which the motorman

stands, is also inclosed in glass, so that one can see forward

and backward as well as to the sides. The railway, which was opened

March 1, 1901, has now been running sixteen months. In the beginning

the townspeople, who get on and off every few minutes at a station,

were curious about the railway; so many thousands scrambled to

be among the first to ride through the air that the traffic had

often to be suspended. Once, as a German newspaper solemnly announced,

in the station shown in the first picture a car window was actually

broken—whereupon the police were hurriedly called in, and

they ordered the road closed for the day! Now that we understand something

about it, we enter by the door at the side of the car, first passing

through the little gangway from the platform. The door is locked

after us, and without noise or jar the car starts. The windows

are large, and there is a glass door at each end besides those

on the side of entry; a platform to the front, on which the motorman

stands, is also inclosed in glass, so that one can see forward

and backward as well as to the sides. The railway, which was opened

March 1, 1901, has now been running sixteen months. In the beginning

the townspeople, who get on and off every few minutes at a station,

were curious about the railway; so many thousands scrambled to

be among the first to ride through the air that the traffic had

often to be suspended. Once, as a German newspaper solemnly announced,

in the station shown in the first picture a car window was actually

broken—whereupon the police were hurriedly called in, and

they ordered the road closed for the day!

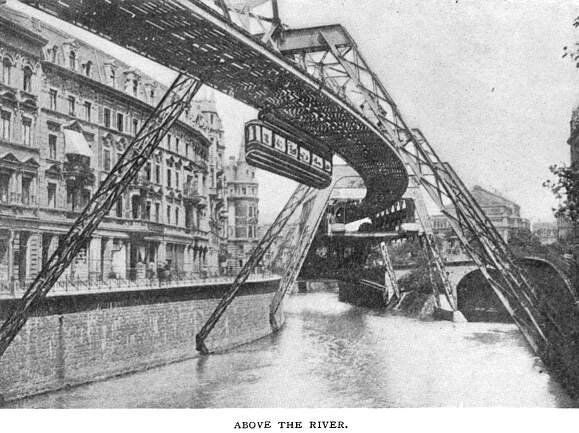

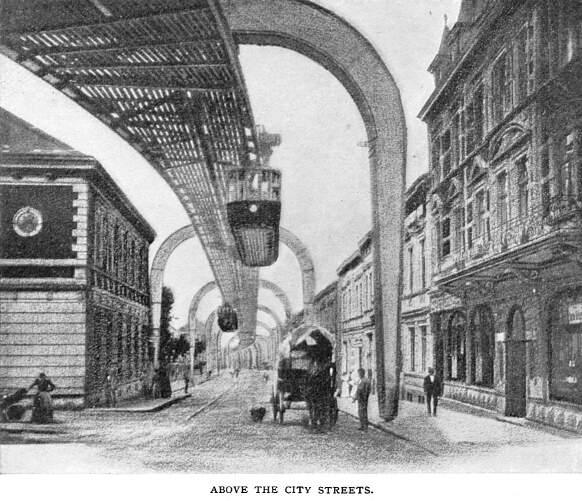

For a long way the car travels over the river between the rows

of houses and factories. You can see how it looks from the picture

of the structure as it straddles the stream. Here the supports

look like big A's with very slanting sides and square tops; over

dry land, as you see by the last picture, the supports to the

railway are like big U's upside down. The Wupper is a narrow,

dirty stream of many colors, like Joseph's coat, for the refuse

of the dye and chemical works which line its sides give it more

hues than has the rainbow. While passing above, you look down

on a stream that is, by turns, yellow, brown, magenta, and many

other shades, but never a natural water-color.

Standing in the car, it is necessary to steady one's self;

altogether, though, there is very little jarring, and one feels

like a bird looking down in this fashion on the world. This is

especially the case when the car finally quits the river and travels

over the road toward Vohwinkel, as the highway is lined on both

sides by fine trees.

When I was a little girl and

firmly believed every word of the "Arabian Nights,"

I used to sigh for a magic horse which would soar through the

air without spilling me off. That horse, I feel, will never appear;

but perhaps a substitute for him might be found in the magic coach

in which one seems to float, during this part of the route, through

a green bower. The illusion is heightened by the noiseless flitting-by

of cars traveling the other way. There is nothing picturesque

in the New York elevated railway, as all of you who live near

that city know, excepting sometimes at sunset in the spring when

a brightly lighted train, pictured against a glowing sky, flies

past the opening of a cross-street, and the chance observer catches

at the same time the shimmer of the river beyond. Novelty and

nature, however, throw a charm over a large part of the route

of the Suspension Railway. The scheme of building it as far as

possible over the Wupper probably arose from the desire to have

direct and speedy communication between the two ends of the sister

towns without going uphill and down dale. Certainly the matter

was long and carefully pondered before this form of an elevated

road, the invention of an engineer in Cologne named Eugene Langen,

was decided upon. So successful has the experiment proved that,

as the conductor tells with much importance, there is talk of

extending the railway to Cologne. When I was a little girl and

firmly believed every word of the "Arabian Nights,"

I used to sigh for a magic horse which would soar through the

air without spilling me off. That horse, I feel, will never appear;

but perhaps a substitute for him might be found in the magic coach

in which one seems to float, during this part of the route, through

a green bower. The illusion is heightened by the noiseless flitting-by

of cars traveling the other way. There is nothing picturesque

in the New York elevated railway, as all of you who live near

that city know, excepting sometimes at sunset in the spring when

a brightly lighted train, pictured against a glowing sky, flies

past the opening of a cross-street, and the chance observer catches

at the same time the shimmer of the river beyond. Novelty and

nature, however, throw a charm over a large part of the route

of the Suspension Railway. The scheme of building it as far as

possible over the Wupper probably arose from the desire to have

direct and speedy communication between the two ends of the sister

towns without going uphill and down dale. Certainly the matter

was long and carefully pondered before this form of an elevated

road, the invention of an engineer in Cologne named Eugene Langen,

was decided upon. So successful has the experiment proved that,

as the conductor tells with much importance, there is talk of

extending the railway to Cologne.

Now the German railway man is even less willing to answer questions

than his American mate; and, just as local pride makes this one

communicative, the magic coach comes to a sudden standstill. The

Vohwinkel terminus has been reached in eighteen minutes after

leaving the station in Elberfeld, which lies across the way from

the ordinary railway station.

When, all aglow with the adventures of the day, I sought, on

return to the pretty town from which I had gone, to narrate these

experiences to the good Germans who had suggested the trip, they

shook their heads and said: "So you really tried it, did

you? Perhaps you don't realize what a dangerous river the Wupper

is. Did you know that the refuse from the factories has made mud

at the bottom twelve feet deep, and nothing that falls into it

is ever found?"

Oddities &

Curiousities | Contents Page

|