|

"RAINMAKING" ON THE

CHICAGO, ROCK ISLAND & PACIFIC RY.

Engineering News — February, 1895

Ever since the famous expedition, in the fall of 1891, of Gen.

"Cloud-Compelling" Dyrenforth and his party of assistants

to bombard the skies which overhang the and plains of Texas, there

has been a good deal of popular interest in the subject of rainmaking.

The "bomb" method, by which the atmosphere is "whacked"

with explosions until it sheds drops of moisture like an erring

school boy has yielded its place in popular favor to a more mysterious

process, by which certain unknown gases are poured forth from

a secret apparatus. If the claims of the originators of this process

are to be believed, these gases possess a potency only to be compared

with that of the mysterious "vapors" in the "Arabian

Nights," which, issuing from a tiny casket or a nut were

transformed into a palace, a fortress, an evil genie, or other

object whose volume bore no relation to the size of the original

containing vessel.

During the past two or three years various scattered newspaper

articles have given information concerning the working of this

process at various points; and while we are accustomed to place

small reliance on newspaper reports concerning any technical matter,

our curiosity was aroused by the statement that the Chicago, Rock

Island & Pacific Ry. Co. had interested itself in the matter,

and we, therefore, applied to officials of that company for a

verification or contradiction of the reports. We are indebted

to their courtesy for the following information, which we present

substantially as received, commenting upon it in our editorial

columns.

The system of "rainmaking" used by the Chicago, Rock

Island & Pacific Ry. Co. consists in injecting a gas, or mixture

of gases, into the air which "supply the element lacking

in the atmosphere, in order that rain may fall." The composition

of this gas or mixture of gases is a secret with the inventor,

Mr. C. B. Jewell, of Goodland, Kan., a train despatcher in the

offices of the above railway. In a letter to us Mr. Jewell describes

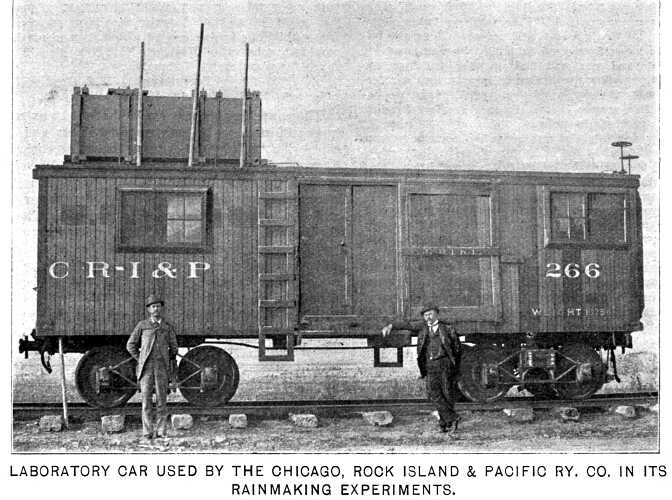

his apparatus and mode of operation in a general way. The laboratory

used in the field is a freight car, at one end of which three

pipes project up through the roof. Each of these pipes divides

into two pipes just inside the car and the six pipes connect with

six jars in which the gases are made. The letter continues:

On the opposite side of the car is a long shelf on and under which

we keep our materials. Directly over this shelf is a second shelf

divided into 13 compartments, in which rests our battery. At the

end of the battery there is a large jug which is filed with a

solution and is connected with the battery, which is also connected

with the six large jars in which we make the gases. The tank shown

on the top of the car is filled with water. This water we prepare

before using, making it as soft as possible. The pipe near the

left end of the car runs from the sink inside to a large hole

dug in the ground to hold the waste. Sometimes this pipe is used

as a ground connection from the battery. The other end of the

car is partitioned off and is used for a sleeping apartment and

office. My entire time is taken up while on the road answering

correspondence, which comes from all parts of the world, and attending

to the machine, which is operated night and day. I have used this

process on the line of this road for two seasons. Last year I

had three cars just like the one I send you photograph of, and

expect to have several more this year. Had there not been such

hard times, several of the railroads in the arid regions would

have used my process in 1894. My materials are furnished in Chicago

by several different houses, and neither house knows what the

other house furnishes, or which the other houses are. The men

who operate the cars for me do not know what they are using, but

simply follow my instructions.

My process has been used 66 times and at no time have I failed

to produce rain, but at four places the rains were mere sprinkles,

and were termed failures, and to save argument were so admitted

by me. These failures were due to very high and changeable winds.

There are no phenomena connected with these artificial rains any

more than with a natural rain. Mind you, we do not make rain.

All we do is to bring about the same conditions which nature

does when rain is produced, and when we do this a natural

rain will fall. Nature and her laws are never wrong, and all efforts

in this line must be made in accordance with the laws of nature,

or failure must follow.

Briefly described, therefore, the rainmaking system of the

Rock Island road is to run one or more cars into the territory

which needs rain and start the manufacture of the mysterious gases

which escape through the pipes in the car roof. An effort has

been made to get a description of some of the phenomena attending

one or two of these rains, but nothing of much value has been

secured. The following letters give the most definite information:

Sir: In answer to your favor permit me to relate the actual experiments

which were made here about two years ago. We were suffering for

want of moisture, and I made application to our official department

to have

Rainmaker Jewell come here and make a test. At about 2 p.m.

he commenced operation, the skies were cloudless, and at about

5 p.m. the clouds began to appear, and at 9 p.m. we had a rainfall

of 0.78 inches, as shown by the government gage. This included

his first test at this point. The second test was followed by

better results, there being a precipitation of 1 in. of rain.

In the spring of 1894 we had him here again, the weather was cool

and the experiment was not a success, which I firmly believe was

due to the unfavorable weather. The last experiment was conducted

by H. Hutchinson, one of Mr. Jewell's substitutes, and who is

not well versed in the science of electricity, which is an essential

factor in tests of this nature. There is one point in your letter

which I failed to answer, and that was the territory over which

the rainfall extended. I would call it a local rain, as it did

not extend over a radius exceeding 30 miles. I have no interest

in Mr. Jewell's rainmaking scheme, and have given you the plain

facts, as I was very much interested in the matter and gave it

close attention.

Yours truly, J. B. Bailey.

Phillipsburg, Kan., Jan. 29, 1895.

Sir: Mr. Jewell gave us a fine shower in, I think, three days.

He stationed one car at Mankato, one here and one at Beatrice,

Neb. We had a heavy rain from east of Beatrice to west of Mankato,

about 60 miles. I do not remember what the fall of water was,

but think it was 3½ his. I have all confidence In Mr. Jewell's

power to produce rain.

Yours truly, J. A. Whittemore.

Belleville Kan., Jan. 26, 1895.

(We comment upon this letter in the editorial columns. "Can We Make It Rain?"-Ed.)

CAN WE MAKE IT RAIN?

"Can we make it rain?" is certainly the modern counterpart

of the question propounded to Job by the voice from the whirlwind:

"Hath the rain a father?" The paternity of the rain

has indeed been claimed by men in all ages, and the modern claimant

differs from his predecessors only in having used "science"

instead of superstition in the conception of his offspring. In

another column we have outlined briefly the work of rainmaking,

which the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Ry. has been conducting

during the two seasons past, and proposes to continue during the

coming summer on such of its lines as penetrate the arid and semi-arid

regions. The evidence for and against the claim that rain has

been actually produced through the efforts of these rainmakers

we lay before our readers for what it is worth. In sifting this

evidence, it is well to consider for a moment how rain is produced

in nature. The aqueous vapor of the atmosphere which condenses

into cloud, and falls as rain, is derived from the evaporation

of water, partly from the earth, but mostly from the ocean. A

warm air holds more moisture than a cold air; and consequently

if a saturated air is cooled, it precipitates part of its moisture,

or, in other words, it rains. It is now generally held that dynamic

cooling is, if not the sole cause, at least the principal cause

of rain. By dynamic cooling is meant the cooling of air due to

expansion when raised in altitude and brought under less pressure.

There are several different ways in which the air at the surface

of the earth may be raised in altitude; but whatever the manner

and whatever the altitude, the air must reach the point of saturation

before the resulting expansion and cooling can produce rain. The

reason why the and regions of the earth are arid is simply and

solely because geographical and meteorological conditions are

habitually such that moisture-laden winds are deprived of their

moisture before reaching them, or, on the other hand, because

there is nothing to cause the cooling of these moisture-laden

winds and the consequent precipitation.

But, supposing the aqueous vapor exists in the air somewhat

below the point of saturation, is it not reasonable to suppose

that there may be some way of hastening or forcing condensation,

so that rain will fall? If we trace the history of scientific

rainmaking, we find that it is upon this hypothesis that most

of the various theories are based. The best known and probably

the oldest of these theories is that the agitation of the atmosphere

Produced by violent explosions acts to concentrate the particles

of moisture, until it falls as rain. The popular belief that great

battles have always been followed by rain has been much used as

an argument in favor of this theory. Aside from the fact that

this belief was prevalent long before the days of explosives,

a careful summary of the great battles of the world and the character

of the weather following them has shown conclusively that days

of battle were no more likely to be followed by rain than days

when it was quiet all along the line. As our readers will recall,

the United States Government made some investigations of this

"concussion" theory of rainmaking in the fall of 1891,

and through the courtesy of the Department of Agriculture we have

been furnished the barograph diagrams taken to show the amount

of agitation of the air produced by the explosions. These show

that, at a distance of half a mile from the point of explosion,

the movement of the air was not sufficient to rustle the leaves

of a tree, let alone the condensation of the moisture necessary

for the slight rainfalls which followed one or two of the dozen

experiments. In the same way the old belief that large fires,

like our great forest fires, or the Chicago conflagration, brought

rain by the raising of large masses of heated air, which in cooling

formed clouds that expanded into the proportions of local storms,

has been exploded by a similar compilation of facts.

Concerning the latest system of rainmaking, referred to above

as having been taken up by the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific

Ry. Co., we present such information as we have been able to collect

in another column. A word of explanation may be needful, however,

to prevent misunderstanding and to answer in advance the criticisms

of those who may object that "Engineering News ought not

to give space to such 'fakes.'" We conceive it to be the

office of a technical journal to Publish information on all subjects

of technical interest, together with such comment as may aid its

readers to most clearly understand their significance. This alleged

system of rainmaking has become more or less widely known through

various newspaper articles, it has been taken up experimentally

by a great railway corporation, and a large number of witnesses

aver that remarkable results have actually been produced by it.

These facts are sufficient to justify the presentation of information

in these columns, even granting it to be absolutely certain that

the scheme were a pure delusion; for it is as much a part of our

work to expose the false and fraudulent as to present accounts

of excellent work and improvements on former practice.

As for comments upon the system itself, criticism is largely precluded

by the fact that it is entirely secret; and it is, of course,

well understood that secrecy concerning such a thing is in itself

very strong evidence that it is fraudulent. We are, therefore,

obliged to fall back on general principles and to say that, so

far as can be seen, any effective method of causing the precipitation

of rain must operate through some cause proportionate to the effect

produced. The chances are many to one that such materials and

machinery as could be carried in one end of a box car could not

cause the condensation and precipitation of some 60,000,000 tons

of' water over an area of several hundred square miles.

Reference to the article in another column will show that it

is actually such an effect as this which is claimed for Mr. Jewell's

rainmaking process. It is alleged by one witness that a rainfall

of 0.78 inches, extending over a radius of some 30 miles, occurred

within seven hours of the time the "rainmaker" began

operations. Reducing this radius by one-third, to allow for smaller

precipitation in the outlying territory, we have still an area

of over 1,200 sq. miles, and a precipitation of 0.78 in. means

the fall of some 50,000 tons of water on a square mile. Other

arguments of equal strength might be presented to show the improbability

that the discharge into the air of any gas known to chemistry

could cause condensation and precipitation over a wide area. As

for the alleged successes, it must be remembered that because

a rainfall occurs at a certain time and place is no proof that

rainmaking operations carried on at that time and place had anything

to do with it.

On the other hand, our knowledge of meteorology is not on the

same basis of mathematical certainty as our knowledge of thermo-dynamics,

for example. We cannot say positively that by no possible methods

can a man cause the rain to fall, much as we may feel the exceeding

improbability that rain can ever, be produced by artificial means.

The proper attitude of the engineer or scientist on this question,

therefore, is to hear and weigh evidence without, prejudice. If

Mr. Jewell can water the great American desert with such simple

and inexpensive machinery, as he claims, we shall be glad to see

him prove it, even though we realize that the chances are many

thousand to one that his shrewdness as a weather prophet lies

at the bottom of any success he may have achieved, and that the

juice which he distills with his secret apparatus is merely concentrated

essence of humbug.

Oddities

| Contents Page

|