A TRIP WITH A PROFESSIONAL

RAIN-MAKER

St. Nicholas Magazine—1900

(Founded on Fact.)

BY THE REV. CHARLES M. SHELDON.

"ALL aboard!"

"All right, here!

The brakeman at the rear raised his hand, the conductor swung

himself on, the brakeman followed, and I had a glimpse of a row

of curious faces on the platform of the station looking into the

open door of the car in which I was seated as I drew past them.

But I was too much interested in my surroundings to pay much attention

to outside matters.

I had been attached to the United States Signal Service in

one of the Western States, and obtaining leave of absence for

two weeks, I had also, by dint of careful and, influential correspondence

with the division superintendent of the X. R. R., obtained permission

to make a trip over the road with the professional rain-maker

employed by the company.

The car in which I was seated was divided into two compartments.

One of them was fitted up with sleeping and dining arrangements;

the other contained the mechanical and electrical appliances used

by the rain-maker, It was in the professional end of the car that

I was seated, watching the rain-maker as he busied himself with

certain pieces of apparatus that looked as mysterious to me as

if they had been the stock in trade of a necromancer.

Presently he finished his task and came and sat down beside

me. The car was arranged with narrow doors in the sides. We sat

looking out on the prairie as we sped dustily along, and the rain-maker

answered my questions with good-natured amusement at some of them.

"How does the railroad company regard this department?—as

an advertisement or a necessity?"

"Why, it is a regular part of the service this summer.

There are three cars fitted up like this one, and they cost the

company four hundred dollars a week when everything is going."

"And do you regard it as a regular profession, or—"I

saw the rain-maker color up a little and hastily changed my question.

"Of course I mean, do you regard it as really settled that

rain can be compelled by artificial means, or is the whole thing

still in a stage of experiment?"

"You will have to judge of that by the results of this

trip. There is no doubt in my own mind of certain scientific well-established

natural phenomena."

I looked curiously around the car again.

"Will you explain the meaning of some of these arrangements?"

"Certainly. You will understand them better when we begin

the actual work. This box running the entire length of the car

overhead contains eight hundred gallons of water. These pipes,

here, running down the sides of the car, connect with a rubber

hose, which in turn connects with a hole that will be dug under

the car in the ground where we are side-tracked at our destination.

"Under this broad shelf you see these boxes. I cannot

tell you what is in them, as that is part of my secret. However,

by chemical combinations certain gases are forced from these boxes

through the water and from these pipes, here,"- he put his

hand on them as he spoke,-" the gases escape freely into

the air."

"You have a large 24-cell battery there, too. Of what

use is that?"

"That also is a part of my secret. Rain making is largely

an electrical as well as chemical matter."

The whole affair was mysterious

to me, and the "professor's" explanations only added

to the mystery. However, he continued: The whole affair was mysterious

to me, and the "professor's" explanations only added

to the mystery. However, he continued:

"When the entire apparatus is in operation some fifteen hundred

feet of gas escape into the air every hour. When released it is

warm, and being much lighter than the air, ascends rapidly. I

have a way of measuring the altitude, and know that in some cases

the gas has risen nearly eight thousand feet.

"A good deal depends on the velocity of the wind, the

general condition of humidity, etc. I do not say that I can always

produce rain at the point of operation, because the wind has so

much to do with it, and my experiments may result in rain at a

distance."

"But still you believe that by your arrangements here

with the gases, and so on, you can in a dry time produce rain

that would not otherwise have fallen in the course of nature?"

The rain-maker looked at me quizzically, but did not answer,

except to refer me to the coming experiments, to which I began

to look forward with a curiosity I had not felt for years.

To tell the truth, I had no faith in the power of the rain-maker's

combination of chemicals and electricity to produce a drop of

moisture. I had read of his claims to do so, and had seen the

circulars of advertisement sent out by the road, but I wanted

to see for myself; and as the time drew near when it seemed possible

to judge for myself, my interest in the trip grew with every dusty

mile covered by the train.

It was nearly dark when we drew up at the town where we were

to be side-tracked and left to make the trial. It was a railroad

town, with a group of shops and three or four smelters. We were

backed upon the siding, uncoupled from the train, which went on,

and at once the rain-maker made his preparations for letting the

gases out into the air.

A crowd of curious men and boys had gathered, knowing that

the rain-maker was coming. A committee of citizens from the town

was on hand. The committee had secured the services of the "professor"

by making certain terms with the road. Some of them came into

the car and stared at the sight of the bottles, battery, pipes,

shelves, tanks, and so forth, which made such a curious display.

A great many questions were asked, to which the rain-maker gave

short and unsatisfactory replies.

By this time it was dark, and the apparatus was in shape. The

battery was turned on, and in a few moments I was informed that

the gases were being liberated. There was little noise in connection

with the work, and the whole thing was very undemonstrative.

"We might as well eat our supper now," said, my companion.

Don't you have to watch anything?

"No; it goes itself," he answered. "That's the

beauty of it."

So we went into the other end of the car and had a hearty supper,

the company furnishing a good bill of fare, and supplying a colored

servant who cooked and did the work.

I shall never forget the next twenty-four hours spent in that

strange rain-maker's-car. The experiences of such a trip could

probably be duplicated in no other country in the world than the

United States.

The prairie was illuminated by the moonlight, which made every

dusty blade of grass and every curled rosin-weed look drier and

deader than they looked by day. There had been no rain in the

neighborhood for three weeks. Unless rain came inside of forty-eight

hours the entire corn crop of the country would be ruined by the

hot winds which bad already begun to blow.

We opened the side doors of the car for the circulation of

air. The rain-maker went about among his bottles and pipes and

arranged them: for the night, so that fresh material could be

on hand. Then he came and sat down by me again.

"How long will it take before signs of rain appear?"

"It depends on many things—wind, velocity, humidity,

electric disturbance, and many other circumstances."

"What is your opinion about success this time?"

"I think we shall get a storm within twenty-four hours."

I did not say anything. To get a little exercise I stepped

out of the car and strolled up, the main track to the little station.

I was surprised to find a large gathering of men there.

"What's going on?"

"Haven't you heard? The big strike is, on, and all trains

on the line have stopped running."

It was true. The greatest railroad strike ever known had begun,

and there we were, stranded in that railroad town full of desperate

men, and no telling when we could pull out!

I went back to the car and told the rain-maker. He was an old

railroad man, and did not seem impressed with the news at all.

He said he guessed we would get away when we got ready.

I slept very little that night. I was conscious of strange

noises and a feeling that something unusual was going on in the

town and around the shop near by.

In the morning we looked out upon the same dusty, bleak, hot

prairie. The sun rose hot and burning. There was not a cloud to

be seen anywhere. As the day wore on, news of the great strike

came over the wires. Not a train went through the town. The railroad

men in the shops went out on the strike at noon. Our car was surrounded

by a perfect mob of men and boys all day. Some of them made threats

against the company's property; but we thought nothing of them.

There was feeling of excitement on all sides.

Just as the sun went down at the close of one .of the strangest,

driest, hottest days I ever knew, a bank of cloud appeared just

above the southwestern horizon. The rain-maker had seen it, but

I pointed to it and asked him about it. He replied in a doubtful

tone, and at that moment I was amazed to see, coming around the

curve beyond the station, a long freight-train.

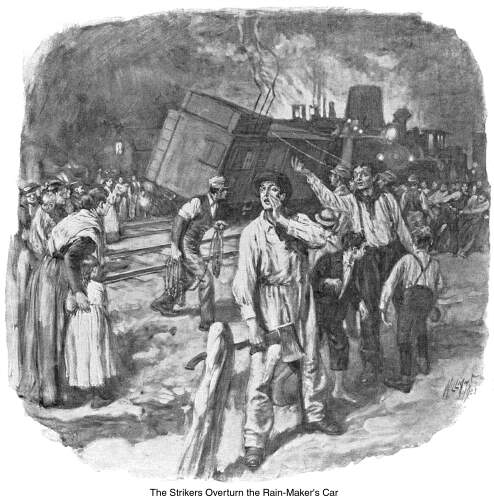

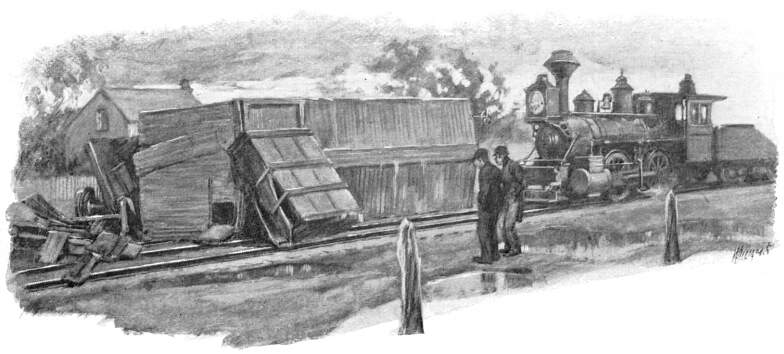

A tremendous crowd began to stream down to the tracks. In a

few minutes it seemed as if every inhabitant of the town was surging

about that freight. It had managed in some way to get over the

road from the station below. In a very few minutes the mob had

uncoupled the engine, after backing the cars upon the siding next

to our car. We felt the jar of the cars as they stopped, and we

were then pushed slowly up the siding until we were at its extreme

end, where we were stopped. It was the evident intention of the

strikers to prevent the train from going any farther.

Two hours went by. Meanwhile we had felt obliged to close the

doors of our car to ,shut out the mob; and in the close, hot little

room we proceeded to spend the night as comfortably as we could.

I had made my arrangements to sleep, and had, in fact, in spite

of the excitement of the evening, supposed that all was going

to settle down again, when a shout outside brought me up standing,

and the rain-maker and I pushed open one of the side doors a little

way to look out.

A mass of men could be seen gathered about one of the smelters,

which was situated a quarter of a mile up the track and close

beside it. And as we looked up there, the foremost of them grew

more distinct. A pale light glowed over them. It grew brighter,

redder. The rails of the track not covered by the mob glistened

in it; and soon a stream of flame burst out of a window and ran

up one of the gables.

The strikers had fired the smelter! As we watched them and

heard their shouts, we grew serious. A large group of men could

be seen running down the track toward us. They stopped on the

other side of the switch from a the siding, and by the light of

the burning smelter we could see them tearing up the rails.

Their numbers were increased every moment, and the siding on

which the freight-cars stood was soon surrounded by hundreds of

excited men.

The rain-maker closed the door and locked it. He then secured

the other door in the same way. A small lamp had been burning

on a shelf. He blew it out and whispered to me: "It's our

best chance of escaping notice. The men are excited; they have

been drinking, and there is no telling what they may do, now their

blood is up."

So there seemed nothing better to do than to sit down and let

events take their course. Ten minutes went by. We felt the noise

and confusion outside increasing. Suddenly a strange crash was

heard. It sounded close by, but what it was we could not guess.

It was followed by another and another, each nearer than the first,

and accompanied with great yells and cries.

"What can they be doing?" I could not help asking.

At that instant, before my companion could answer, a peal of

thunder rolled over the prairie and above the shouts of the mob.

The rain-maker smiled at me, as much as to say, "I told you

so"; and what he would have said I do not know, for the next

moment we felt the car sway violently up and down, as if caught

on the swell of an earthquake.

The heavy trucks went up on one side, and then came down with

a jar that smashed nearly every bottle on the rain-maker's shelves.

There was an awful yell from the mob, and again the car rose on

one side, as if being lifted by giant hands.

"Great heavens!" cried the rain-maker. "They

are trying to tip the car over!"

It was true. The mob had resorted to this method of destroying

railroad property, and the crashes we had heard had been made

by the overturning of cars. Ours, being like the rest on the outside,

may not have been distinguished by the men.

At any rate, we were in the fury of the crowd. We tried in

vain to unlock the doors and get out. We screamed and pounded

on the doors, but the car rose, swayed on the trucks sickeningly

for one second, and then over it went, with us inside!

The crash that followed so stunned me that for a while I did

not realize what had happened.

My first return of clear ideas came on finding that I was drenched

with water, and dripping as if in a river. I thought at first

of the rain-maker, curiously wondering if he thought this was

the scientific way of producing moisture. The tank in the top

of the car had broken open, and the water had splashed out all

over us.

The side of the car had split in such a way that I was able

to crawl up from where I lay and get my head and shoulders out.

By this time some of the more sober men in the crowd realized

the situation. I was half kindly, half roughly dragged out from

the broken car, bruised and bleeding, but with no bones broken.

Next I saw the rain-maker standing near the track, his face cut

with broken glass, and one arm broken. The colored cook was nearly

killed by fright, but he escaped with severe bruises.

I spent the rest of the night in the home of a private citizen

who kindly cared for the professor and myself. The strike continued

a week longer, and we were unable to get away even if we had felt

well enough.

I should say, to make the story complete, that on that memorable

evening, about midnight, a tremendous thunder-storm burst over

the town, and drenched the country for miles around. My friend

the rain-maker claims that storm as the result of his scientific

efforts. I have my doubts as to the origin of the rain; but it

will probably be a long time before I take another trip with a

professional rain-maker.

Oddities &

Curiousities | Contents Page

|