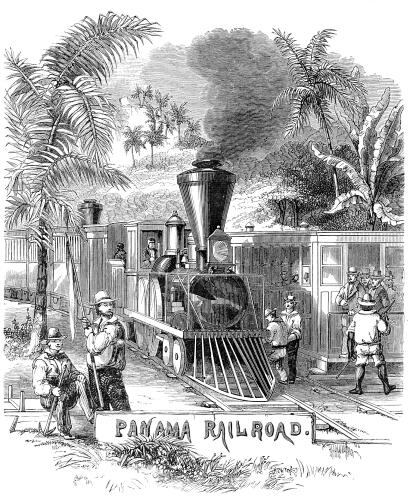

A TRIP ON THE PANAMA RAILROAD.

Panama in 1855. An Account of the Panama Railroad;

of the Cities of Panama and Aspinwall;

with Sketches of Life and Character on the Isthmus. By Robert

Tomes. Harper and Brothers.

"WOULD you like to go to Panama?" was the question

propounded to one of our esteemed contributors. The track of the

Panama Railroad had been completed from ocean to ocean, and the

Company that had for five years been so lavishly

casting its dollars upon the fever-haunted Isthmus, in the confident

hope of finding them again, with increase, after many days, had

resolved to give a grand celebration with wining and dining and

speechifying, in honor of the event. Company that had for five years been so lavishly

casting its dollars upon the fever-haunted Isthmus, in the confident

hope of finding them again, with increase, after many days, had

resolved to give a grand celebration with wining and dining and

speechifying, in honor of the event.

It was January, and the thermometer stood at zero in New York,

and mortal man could not be expected to resist the temptation

to visit the tropics free of expense. So our friend returned an

answer of acceptance to the formal note inviting him to assist

in commemorating the important event, and instituted a search

into the receptacles which contained last year's summer wardrobe,

in preparation for the trip.

On the 5th of February the good steamer George Law left

the wharf at New York, bearing, in addition to its usual miscellaneous

crowd of Californian emigrants, the company of invited guests,

and the United States Minister to Granada. A "Notice"

to passengers, conspicuously posted up, intimating that no deadly

weapons were to be worn on board, and no fire-arms discharged,

and that it was out of order for any person to make his appearance

at the dinner-table with his coat off, might have been a little

startling to the nerves of a timorous or fastidious person; while

the ostentatious display of life-preservers" hinted at the

possibility of drowning too plainly to be altogether agreeable

to one who was not insured against that mode of leaving the world,

by a premonition that he was reserved for a certain other fashion

of exit.

Nobody, however, was shot, stabbed, or drowned, and the brave

vessel, passing within sight of the green hills of Cuba and Hayti,

and the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, dashed with never-resting wheels

among the islands of the Caribbean Sea, and at length, on the

eleventh day, lay motionless as a captured whale, at the dock

at Aspinwall, the Atlantic terminus of the Panama Railway.

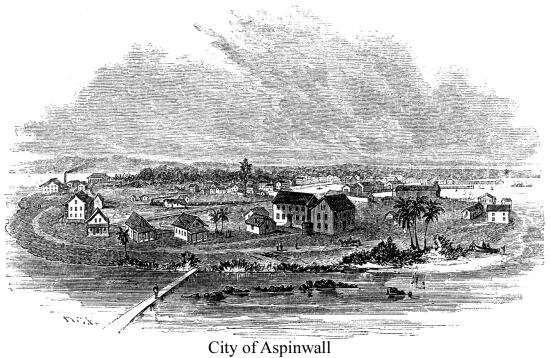

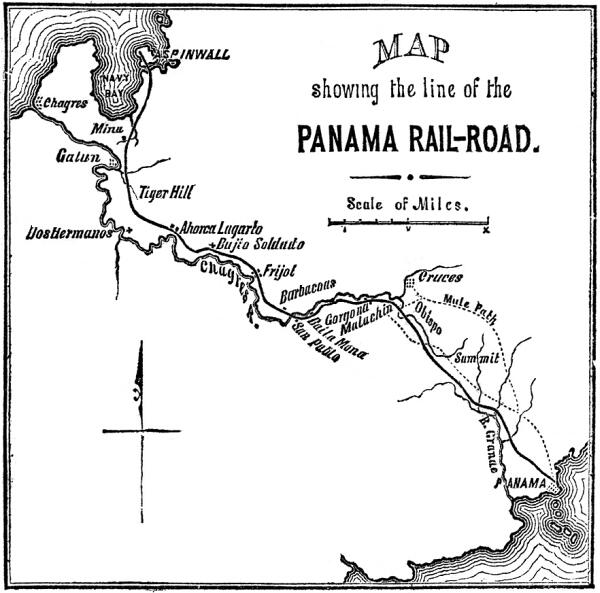

If the map proudly displayed by the enthusiastic

draughtsman of the Company is to be accepted as prophetic, Aspinwall

is destined to be a wonderful city. Broad avenues—A, B, C,

and so on far down the alphabet—are intersected by streets,

to designate which whole squadrons of Roman numerals are pressed

into service. Magnificent docks give proof that the interests

of commerce are to be duly cared for; while the noble Boulevard

surrounding the city, as the "ocean strewn" girdled

the shield of Achilles, and a spacious "Central Park,"

show that devotion to the "Almighty Dollar," the tutelar

genius of America; was not the sole passion in the hearts of the

projectors. If the map proudly displayed by the enthusiastic

draughtsman of the Company is to be accepted as prophetic, Aspinwall

is destined to be a wonderful city. Broad avenues—A, B, C,

and so on far down the alphabet—are intersected by streets,

to designate which whole squadrons of Roman numerals are pressed

into service. Magnificent docks give proof that the interests

of commerce are to be duly cared for; while the noble Boulevard

surrounding the city, as the "ocean strewn" girdled

the shield of Achilles, and a spacious "Central Park,"

show that devotion to the "Almighty Dollar," the tutelar

genius of America; was not the sole passion in the hearts of the

projectors.

It must be confessed that the real Aspinwall hardly corresponds

with the ideal existing in the mind of the enthusiastic artist,

as our friend the Doctor—for we may as well give him his

official title—discovered when he set out on a tour of exploration.

"A hundred or so," he says, "are about the whole

number of houses in Aspinwall. Upon the beach at the northern

end of the island are a few scattered buildings, gay with white

paint and green blinds, chiefly occupied by the officials of the

Panama Railroad, while to the right of these are the works and

depot of the company with machine shops and reservoirs. The shore

at the north curves round, leading easterly to an uncleared portion

of the island, where a narrow rim of white beach separates the

sea from the impenetrable jungle. As we turn westerly and follow

the shore, taking the Mess House as the point of departure, we

come upon a building of corrugated iron in progress of erection,

intended for the residence of the British Consul, if he will ever

have the courage to live in what is only a great target for all

the artillery of heaven. The lightning during the rainy season

keeps it in a continual blaze of illumination, and I mourned,

in common with Colonel Totten, whose house is next door, over

several prostrate cocoa-nut palms, which had been struck down

in consequence of their fatal propinquity to the iron-house. As

we proceed we pass three wooden, peaked-roofed cottages, with

green blinds and verandas, inhabited by employees of the Company;

hurry past some ugly whitewashed buildings, which the palefaced

sailor and the melancholy convalescent negro, sitting smoking

their pipes on the steps, remind us are hospitals, and soon passing

by some outlying hats with half naked negresses and pot-bellied

children sunning themselves in front, we make our way into the

thicker part of the settlement over marshy pools corrupt with

decaying matter, black rotten roots of trees, and all kinds of

putrefying offal, which resist even the street-cleaning capacities

of those famous black scavengers, the turkey-buzzards, which gather

in flocks about it. We now get upon the railroad track, which

leads us into the main street. A meagre row of houses facing the

water, made up of the railroad office, a store or two, some half

dozen lodging and drinking establishments, and the `Lone Star,'

bounds the so-called street on one side, and the railroad track,

upon its embankment of a few feet above the level of the shore,

bounds the other.

"There is another and only one other street, which you

reach by crossing a wooden bridge, that a sober man can only safely

traverse by dint of deliberate care in the daytime, and a drunken

man never, and which stretches over a large sheet of water that

ebbs and flows in the very centre of the so-called city. This

second street begins at the coral beach at the northern end of

the island, and runs southward until it terminates in a swamp.

At the two extremities houses bound it on both sides; in the middle

there is a narrow pathway over an insecure footbridge, with some

tumble-down pine buildings on one side only, with their foundations

soaking in the swamp, their back windows inhaling the malaria

from the manzanilla jungle in the rear, and their front ones opening

upon the dirty water, which we have already described, that fills

up the central part of the city. The hotels—great, straggling,

wooden houses—gape here with their wide open doors, and catch

California travelers, who are sent away with a fever as a memento

of the place, and shops, groggeries, billiard-rooms, and drinking

saloons thrust out their flaring signs to entice the passer-by.

All the houses in Aspinwall are wooden, with the exception of

the stuccoed Railroad office, the British Consul's precarious

corrugated iron dwelling, and a brick building in the course of

erection under the slow hands of some Jamaica negro masons. The

more pretentious of the wooden buildings were sent out from Maine

or Georgia bodily.

"The inhabitants of Aspinwall—some

eight hundred in number—are of every variety of race and

shade in color. The railroad officials, steamboat agents, foreign

consuls, and a score of Yankee traders, hotel-keepers, billiard

markers, and bar-tenders, comprise all the whites, who are the

exclusive few. The better class of shop-keepers are mulattoes

from Jamaica, St. Domingo, and the other West Indian Islands,

while the dispensers of cheap grog, and hucksters of fruit and

small wares are chiefly negroes. The main body of the population

is made up of laborers, grinning coal-black negroes from Jamaica,

yellow natives of mixed African and Indian blood, and sad, sedate,

turbaned Hindoos, the poor exiled Coolies from the Ganges." "The inhabitants of Aspinwall—some

eight hundred in number—are of every variety of race and

shade in color. The railroad officials, steamboat agents, foreign

consuls, and a score of Yankee traders, hotel-keepers, billiard

markers, and bar-tenders, comprise all the whites, who are the

exclusive few. The better class of shop-keepers are mulattoes

from Jamaica, St. Domingo, and the other West Indian Islands,

while the dispensers of cheap grog, and hucksters of fruit and

small wares are chiefly negroes. The main body of the population

is made up of laborers, grinning coal-black negroes from Jamaica,

yellow natives of mixed African and Indian blood, and sad, sedate,

turbaned Hindoos, the poor exiled Coolies from the Ganges."

Notwithstanding the profuse hospitality of his hosts, with

Champagne cocktails and choice Havanas ad libitum, the

Doctor could not find it in his heart to be grieved at the announcement

that the grand expedition across the Isthmus was about to be made.

In addition to its own habitual fever, Aspinwall was in a fever

of excitement in anticipation of the great event. Speeches and

counter-speeches were to be delivered, and duly reported for the

New York Press. Those who expected to be "most unexpectedly

called upon to fill a gap," showed a praiseworthy diligence

in preparing the materials, and in rehearsing their speeches to

each other, so as to provide against any possibility of failure.

The appointed hour at length came and the train left the depot,

amidst a general waving of the star-spangled banner from the shipping,

and a display of miniature copies of the same from the hotels

and drinking saloons while from the balcony of the "Lone

Star" a. single white female waved her white handkerchief

in adieu. The negroes were especially delighted. A party of them

had taken possession of a rusty old cannon, which they kept firing

off with uproarious glee that was soon turned to wailing, when

one of them was mortally wounded by a premature discharge. The

poor Coolies alone were apparently unmoved amidst the general

excitement. They gazed with Eastern apathy upon the scene. What

mattered it to them that another link was completed in the chain

that binds together the Ocident and the Orient?

"For seven miles the road passes through

a deep marsh, in which the engineers, during the original survey,

struggled breast-high, day after day, and yet, in spite of such

toilsome and perilous labor, fixed their steady eyes straight

forward, went on step by step, and accomplished their purpose.

These seven miles are firm now as a stone pavement. Piles upon

piles have been driven deep down into the spongy soil and the

foundation covered thick with a persistent earth, brought from

Monkey Hill, which overhangs the railroad track two miles from

Aspinwall. "For seven miles the road passes through

a deep marsh, in which the engineers, during the original survey,

struggled breast-high, day after day, and yet, in spite of such

toilsome and perilous labor, fixed their steady eyes straight

forward, went on step by step, and accomplished their purpose.

These seven miles are firm now as a stone pavement. Piles upon

piles have been driven deep down into the spongy soil and the

foundation covered thick with a persistent earth, brought from

Monkey Hill, which overhangs the railroad track two miles from

Aspinwall.

"On we go, dry shod, over the marsh, through the forest,

which shuts out with its great walls of verdure on either side,

the hot sun, and darkens the road with a perpetual shade. The

luxuriance of the vegetation is beyond the powers of description.

Now we pass impenetrable thickets of mangroves, rising out of

deep marshes, and sending from each branch down into the earth,

and from each root into the air, offshoots which gather together

into a matted growth, where the observer seeks in vain to unravel

the mysterious involution of trunk, root, branch, and foliage.

Now we come upon gigantic espaves and coratos, with

girths of thirty feet, and statures of a hundred and thirty feet,

out of a single trunk of which, without a plank or a seam, the

natives build great vessels of twelve tons burden.

"Again we cross a stream, rippling between banks of verdant

growth, where the graceful bamboo waves over the water its feathery

top, and the groves of the vegetable ivory palm, intermingled

with the wild fig-tree, spread their shade, and rustling gently

in the breeze, whisper a slight murmur of solitude in the ear,

and surest a passing dream of repose."

At Gatun, seven miles from Aspinwall, the first halt was made.

We who remained at home read in the papers gorgeous accounts of

the triumphal arch flung over the road, and the irrepressible

burst of enthusiasm which greeted the passing train. Our author's

recollections of the scene hardly come up to the florid description

of the enthusiastic reporter. He remembers having seen one white

man, two negroes, and a Coolie mounted on the top of a clay bank

in front of a ruinous hut, shouting with all their might, and

firing a salute from an old blunderbuss.

Passing Bujio Soldado, where stands a picturesque cottage which

was formerly the favorite residence of the lamented John L. Stephen,

while upon the Isthmus, the train reached Baracoas, where the

road crosses the Chagres river by a bridge 600 feet in length.

It is built of pine, brought from Georgia. Its massive timbers

seemed as though they might endure for ages; but such is the destructive

character of the climate that in a twelvemonth they must be replaced.

To the west looms up the Cierro Gigante, the loftiest summit upon

the Isthmus whence Balboa saw at one glance the bright waters

of the two oceans. Another short stage brought the train to the

spot which had been selected for the site of a monument to Stephens,

Aspinwall, and Chauncey, the original projectors of the Panama

Road. The train stopped, and two sturdy negroes panted up the

gentle acclivity, bearing the corner-stone of the proposed monument,

and our Minister to Granada delivered a speech, of which copies

were duly forwarded to the papers at home; where we hope it was

read with more attention than seems to have been accorded to it

by hungry listeners.

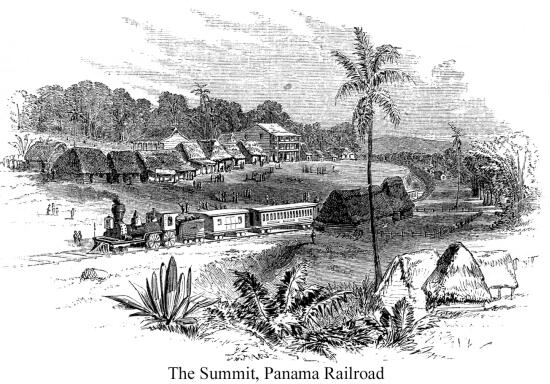

Another seven miles brought the train to the

summit of the line, 250 feet above the level of` the Pacific.

Here has been the heaviest work upon the line. A "deep cutting,"

1200 feet long, and 24 feet deep, has been dug through a soft

soil, which every rain washes down upon the road, requiring a

numerous force of laborer to keep the track clear. A rapid descent

of 70 feet to the mile conquers the descent upon the Pacific side.

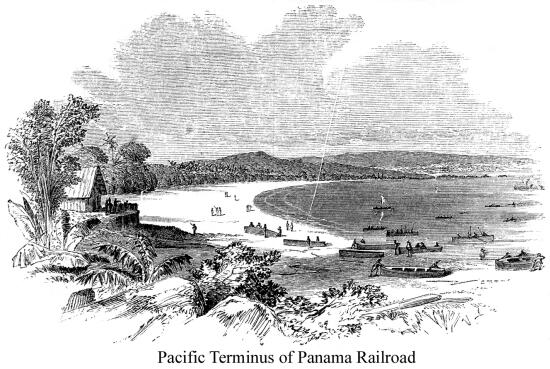

Then a few miles of level track and the train reaches Panama,

stopping on the very verge of the shore of the broad Pacific.

The transit from ocean to ocean has occupied, just four and a

half hours, including the time lost in listening to speeches. Another seven miles brought the train to the

summit of the line, 250 feet above the level of` the Pacific.

Here has been the heaviest work upon the line. A "deep cutting,"

1200 feet long, and 24 feet deep, has been dug through a soft

soil, which every rain washes down upon the road, requiring a

numerous force of laborer to keep the track clear. A rapid descent

of 70 feet to the mile conquers the descent upon the Pacific side.

Then a few miles of level track and the train reaches Panama,

stopping on the very verge of the shore of the broad Pacific.

The transit from ocean to ocean has occupied, just four and a

half hours, including the time lost in listening to speeches.

Panama was very quiet just then. The Californians, going and

returning, had all left for their several destinations, and the

visitors had abundance of leisure to wander about the town and

see the few sights, and observe the people. There is the spruce-looking

Padre, in long silk surplice, lined with pink satin. A cocked

hat, fringed and tasseled, covers his reverend head; and his lower

members are encased in silken hose, and polished shoes with golden

buckles. His golden-headed cane, the jaunty air with which be

puffs his cigar, and the gallantry with which he accosts the females

of his flock, show that he is no anchorite. Then came a slouchy

negro woman, with long black hair streaming down her back. Her

garments are anything but superfluous, and, in accordance with

the custom of the Isthmus, the flounces are at the  top,

instead of the bottom of the skirt. She carries a child astride

upon her hip, which looks as though it was fashioned for that

special purpose. She, too, is smoking the perpetual cigar. Next

may come a mother and child gayly tricked out in loose calico

dresses, of the most flaming colors and startling patterns. Broad-brimmed,

bright-ribboned Panama hats cover their heads; and satin slippers

are stuck upon the tips of their toes. The child is a perfect

fac-simile of the mother in all but size. From hat to slipper

they are dressed alike. One fancies that he is looking at the

mother through a spy-glass reversed. They evidently belong to

the upper class, and are fully aware of the magnificence of their

appearance, as they pace along in conscious pride through the

streets. Another characteristic denizen of Panama presents himself

in the person of the water-carrier, mounted on his mule. He is

just returning from outside the walls, where be has filled his

kegs from the orange-shaded spring, and is now returning to supply

his customers, whose water-jars stand under the balcony, covered

with cool moisture. Into the bung holes he has inserted a tuft

of green leaves, by way of cork; so that, at first sight, one

might suppose his water-kegs had spontaneously germinated, and

were about to grow up, and perhaps produce a crop of diminutive

vessels in their own image and likeness. A shackled mule is cropping

the grass in the deserted Plaza; a group of naked black children

are playing on the church steps; and a file of galley-slaves are

marching through the streets. Inside the churches, devotees are

prostrate before tawdry images of the saints; and frowzy padres

are snuffing the candles and peering into the contribution boxes.

To remind you of home you look into a drinking saloon, where top,

instead of the bottom of the skirt. She carries a child astride

upon her hip, which looks as though it was fashioned for that

special purpose. She, too, is smoking the perpetual cigar. Next

may come a mother and child gayly tricked out in loose calico

dresses, of the most flaming colors and startling patterns. Broad-brimmed,

bright-ribboned Panama hats cover their heads; and satin slippers

are stuck upon the tips of their toes. The child is a perfect

fac-simile of the mother in all but size. From hat to slipper

they are dressed alike. One fancies that he is looking at the

mother through a spy-glass reversed. They evidently belong to

the upper class, and are fully aware of the magnificence of their

appearance, as they pace along in conscious pride through the

streets. Another characteristic denizen of Panama presents himself

in the person of the water-carrier, mounted on his mule. He is

just returning from outside the walls, where be has filled his

kegs from the orange-shaded spring, and is now returning to supply

his customers, whose water-jars stand under the balcony, covered

with cool moisture. Into the bung holes he has inserted a tuft

of green leaves, by way of cork; so that, at first sight, one

might suppose his water-kegs had spontaneously germinated, and

were about to grow up, and perhaps produce a crop of diminutive

vessels in their own image and likeness. A shackled mule is cropping

the grass in the deserted Plaza; a group of naked black children

are playing on the church steps; and a file of galley-slaves are

marching through the streets. Inside the churches, devotees are

prostrate before tawdry images of the saints; and frowzy padres

are snuffing the candles and peering into the contribution boxes.

To remind you of home you look into a drinking saloon, where  the

sallow bar-keeper is concocting a sherry-cobbler for a fever-stricken

Yankee; a brace of dark-haired natives are making wonderful strokes

at the billiard table; and a group of Spaniards and Frenchmen

are playing dominoes and sipping absinthe. This appears to be

about the sum-total of life in Panama. the

sallow bar-keeper is concocting a sherry-cobbler for a fever-stricken

Yankee; a brace of dark-haired natives are making wonderful strokes

at the billiard table; and a group of Spaniards and Frenchmen

are playing dominoes and sipping absinthe. This appears to be

about the sum-total of life in Panama.

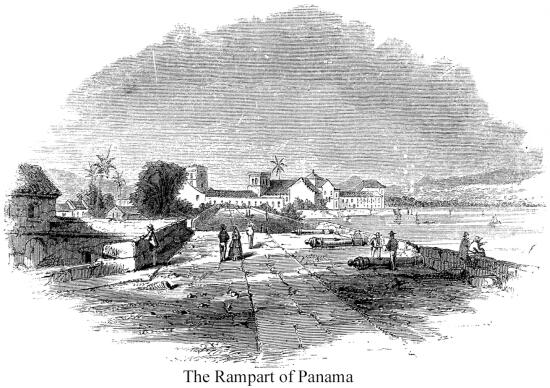

The rampart speaks of the days when the memory of Morgan was

fresh in men's minds. Its solid foundations, laid two centuries

ago, still breast the long waves of the Pacific. But the wall

is in ruins; the loopholes are rent and jagged; the beautiful

guns lie dismounted. A few barefooted mulatto soldiers, clad in

loose linen jackets and trowsers, with red woolen caps on their

heads, smoke their cigars, and strive to keep up the appearance

of a military post. But it is all a sham. The descendants of the

Castilian conquerors, here as every where else, are a worn-out

and effete race. People and town alike have fallen into decay.

The government is too feeble to exercise the ordinary duties of

police, and has been obliged to give into the hands of foreigners

the duty of preserving order on the Isthmus. The right of punishment,

even to life and death, without appeal, has been granted to the

Railroad Company. What the government is unable to accomplish,

is performed by a guard of forty men, headed by Ran Runnels, famed

as a Texas Ranger, who have cleared the Isthmus of robbers, and

keep the thousands of unruly laborers in awe.

Two centuries ago Panama was the centre of

the trade between Europe and Western America. It was a gorgeous

city, whose merchants were princes. Their warehouses were filled

with gold, silver, spices, and precious stuffs; and their dwellings

were adorned with all that wealth could procure. But the discovery

of the passage round Cape Horn turned the trade into a new channel.

With the decline of the Spanish power the last gleam of prosperity

departed; and since the Isthmus has been divided into feeble states,

the decay has gone on with accelerated speed. For a short time

the California emigration infused a spark of life into the stagnant

city. But it was a spasmodic activity. The two thousand foreigners

who were there congregated in 1850, have fallen to a few hundreds;

and the native population was never fairly aroused from their

deathlike lethargy. The majority of the natives are a mongrel

race, in whose veins White, Indian, and Negro blood is mingled

in every conceivable proportion. Yet these are every way superior

to the few who boast an unmixed Castilian descent. It is fearfully

probable that no race of whites can escape deterioration upon

the Isthmus. The indomitable energy which braves every hardship,

and overcomes every visible obstacle, yields to the fatal influence

of the climate; and each generation sinks lower than the one that

preceded it. Yet the prize of the commerce between the East and

the West is too great to be abandoned without a desperate struggle.

It is hardly to be thought of that this narrow Isthmus should

be suffered to add ten thousand miles to the voyage between New

York and San Francisco. Two centuries ago Panama was the centre of

the trade between Europe and Western America. It was a gorgeous

city, whose merchants were princes. Their warehouses were filled

with gold, silver, spices, and precious stuffs; and their dwellings

were adorned with all that wealth could procure. But the discovery

of the passage round Cape Horn turned the trade into a new channel.

With the decline of the Spanish power the last gleam of prosperity

departed; and since the Isthmus has been divided into feeble states,

the decay has gone on with accelerated speed. For a short time

the California emigration infused a spark of life into the stagnant

city. But it was a spasmodic activity. The two thousand foreigners

who were there congregated in 1850, have fallen to a few hundreds;

and the native population was never fairly aroused from their

deathlike lethargy. The majority of the natives are a mongrel

race, in whose veins White, Indian, and Negro blood is mingled

in every conceivable proportion. Yet these are every way superior

to the few who boast an unmixed Castilian descent. It is fearfully

probable that no race of whites can escape deterioration upon

the Isthmus. The indomitable energy which braves every hardship,

and overcomes every visible obstacle, yields to the fatal influence

of the climate; and each generation sinks lower than the one that

preceded it. Yet the prize of the commerce between the East and

the West is too great to be abandoned without a desperate struggle.

It is hardly to be thought of that this narrow Isthmus should

be suffered to add ten thousand miles to the voyage between New

York and San Francisco.

With the commerce between California and the

East for a prize, it would at first sight seem to be no extraordinary

achievement to construct a railway of less than fifty miles in

length, where there were no broad rivers to cross, no rocky ridges

to excavate, and no deep valleys to fill up. But the Panama route

presented obstacles more formidable than these visible and tangible

ones. The materials for the construction and equipment of the

road were all to be brought from a distance. Not only were the

tools and iron work to be conveyed from the United States and

from England, but, although the country abounded in forests, the

very wood upon which the rails were to rest, and of which the

bridges were to be constructed, was the product of Maine and Georgia,

and the food for the laborers must be sought in the markets of

the Atlantic cities. The tropic, climate, which stimulates the

powers of nature, whether of production or destruction, to an

activity unknown in temperate regions, wrought in both directions

with unresting activity against the enterprise. Thick jungles

had to be pierced, which reproduced themselves almost as rapidly

as they were cut down. The way once cleared, if left to itself,

would be overgrown again in a twelvemonth. The destruction of

dead material is as rapid as the growth of the living. A month

does the work of a year. The most solid timber, exposed to the

action of the climate and the insects, decays in a twelvemonth.

Bridges, stations, tanks, houses must be built of stone or iron

to be permanent. With the commerce between California and the

East for a prize, it would at first sight seem to be no extraordinary

achievement to construct a railway of less than fifty miles in

length, where there were no broad rivers to cross, no rocky ridges

to excavate, and no deep valleys to fill up. But the Panama route

presented obstacles more formidable than these visible and tangible

ones. The materials for the construction and equipment of the

road were all to be brought from a distance. Not only were the

tools and iron work to be conveyed from the United States and

from England, but, although the country abounded in forests, the

very wood upon which the rails were to rest, and of which the

bridges were to be constructed, was the product of Maine and Georgia,

and the food for the laborers must be sought in the markets of

the Atlantic cities. The tropic, climate, which stimulates the

powers of nature, whether of production or destruction, to an

activity unknown in temperate regions, wrought in both directions

with unresting activity against the enterprise. Thick jungles

had to be pierced, which reproduced themselves almost as rapidly

as they were cut down. The way once cleared, if left to itself,

would be overgrown again in a twelvemonth. The destruction of

dead material is as rapid as the growth of the living. A month

does the work of a year. The most solid timber, exposed to the

action of the climate and the insects, decays in a twelvemonth.

Bridges, stations, tanks, houses must be built of stone or iron

to be permanent.

But worse than all these is the pestilential climate, with

which no race of men and no strength of constitution can contend;

and against which no measure of precaution and no process of acclimation

is a safeguard. No man could hope to escape the terrible "Panama

fever" for more than a few weeks, or months at most. If the

patient survived the violence of the first attack, the poison

remained in the system, and he could hope for no perfect recovery

so long as he remained on the Isthmus. And those who had apparently

recovered by seeking a more healthy climate, succumbed at once

on their return. "I never met," says our author, speaking

as a medical man, "with a wholesome-looking person among

all those engaged upon the railroad. There was not one whose constitution

had not been sapped by disease."

The laborers upon the road were sought from every country,

and there was a marked difference in the rapidity with which different

races yielded to the miasma. The African resisted it longest;

next came the Coolie; then the European races; and last of all

the poor Chinaman, who succumbed at once. A ship-load of eight

hundred of these poor Celestials landed at Panama. Of these thirty-two

were prostrated almost at the moment of landing; in four or five

days eighty more lay by their side; and in as many weeks there

was hardly one who was fit for labor. They gave themselves up

to despair, and sought for death at once, rather than await its

rapid and inevitable approach. Hundreds destroyed themselves.

Some persuaded their companions to kill them. Some seated themselves

on the beach at low-water, and lighting their pipes, grimly waited

for the rising tide to engulf them. Some strangled themselves,

in default of a better means, with their own cherished pig-tails.

Some impaled themselves upon sharpened stakes or the implements

of their labor. In a space of time incredibly short, six hundred

of the eight were dead, and the miserable remnant, hardly alive,

and wholly unfit for labor, were shipped to Jamaica, where they

linger out a life if possible more wretched than that of their

countrymen whom a heartless cupidity brought to our own city,

and then, failing in its object, abandoned here.

Hardly less terrible was the fate of a shipload of Irish laborers,

fresh from their green island. So rapidly did they give way to

the fearful poison pervading the atmosphere, that not one

of them was ever able to perform a full day's labor; and the miserable

survivors, shipped to New York, died almost to a man of the fever

contracted during their brief stay upon the Isthmus.

Nature seemed determined that the "door of the seas"

should not be opened. Yet in spite of the obstacles which she

interposed, and in spite even of the unexpected cost of the work,

the enterprise went steadily on, until in five years from the

time when ground was first broken, the first locomotive traversed

the whole space from ocean to ocean. It is a wonderful triumph

of man's indomitable will over the hostile powers of nature, visible

and invisible. But the victory has been won at a fearful cost

of life and health. Whether—leaving these out of view, and

looking at the matter in a merely pecuniary point of view—the

enterprise is a success or a failure, is still a question. Wall

Street counts up the millions already expended in the construction

of the road, and the other millions required to keep it in operation,

and shaking its head, asks dubiously, "Will it pay?"

We, certainly, most devoutly hope that it may.

Panama Canal

| Contents Page

|