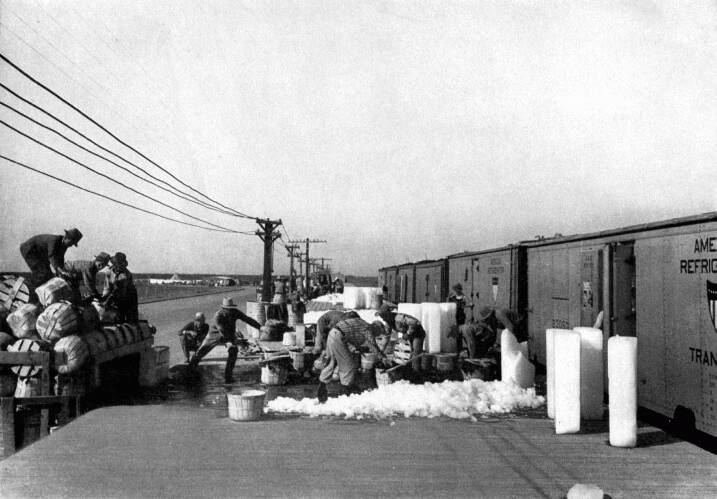

Loading Spinach into a Refrigerator

Car

Loading Spinach into a Refrigerator

Car

When we visit the corner grocery store, with its mixed aromas,

do we ever stop to think where all the fruits and vegetables,

fresh meats, fresh fish, dairy products and other foods come from

and what an important part transportation plays in bringing these

foods to our community?

Do we ever pause to reflect upon the part which railway transportation

plays in assembling the foods that go to make up our daily menu?

Behind every meal we eat is a fascinating story of transportation—fresh

vegetables and fruits that have been transported for hundreds

or thousands of miles; bacon or ham or sausage from the great

packing centers, which draw their supplies from millions of American

farms. And whence come the cereals, the cream, the bread, or the

grain from which bread is made, the butter, the marmalade, the

salt, the pepper, the sugar and other items on our breakfast table?

Several thousand miles of transportation, reaching from a dozen

or more states, far and near, and from distant lands, may be represented

in the typical American breakfast.

In the picture we see men unloading baskets of spinach from

a farm truck and loading them into a refrigerator car. Spinach

is one of numerous farm products which go to make up the million

and a quarter carloads of fresh vegetables, fruits, fish meats,

butter and other perishable commodities which move by railroad

each year. Large quantities of ice are used to keep the products

in good condition.

The long-distance transportation of highly perishable foods

of this nature is distinctly a railroad achievement. At no previous

period in the world's history was it possible for a people to

enjoy such an abundance and variety of foods at all seasons of

the year as we enjoy in America today.

The refrigerator car—America's "ice box on wheels"-makes

this possible. Before refrigerator cars were widely introduced,

perishable foods were marketed only in or near the areas of production,

and the supply and variety of fresh foods were limited.

The first ice-cooled car designed to prevent shipments from

spoiling in transit was introduced by a meat-packing firm in Chicago

in 1857. The first shipments of fruits under refrigeration were

from southern Illinois to Chicago in 1866. To Parker Earle, an

enterprising fruit grower of Cobden, Ill., goes the credit for

pioneering in this development. After several unsuccessful efforts

to ship strawberries to Chicago without their spoiling on the

way, Mr. Earle hit upon an idea. During the winter of 1865-66

he harvested a large quantity of ice, and he packed the ice in

sawdust in his barn so it would keep well into the summer. Then

he built several large wooden chests with double linings. Each

chest was fitted with two compartments. When the berry-picking

season arrived Mr. Earle packed one compartment of each chest

with ice and the other compartment with strawberries. Then he

shipped them by railroad to Chicago. The strawberries arrived

in the Chicago market in perfect condition—several days before

local berries ripened—and Chicago housewives and hotels eagerly

bought them for as high as $1 a quart! Parker Earle reaped a handsome

profit from his crop.

It was only a step from the iced chest to the iced box car,

and Parker Earle was one of the pioneers in this venture also.

By 1872 many carloads of strawberries and other fruits were being

shipped from southern Illinois to Chicago under refrigeration.

In 1885 berries from Virginia were shipped to New York under refrigeration.

Three years later Florida oranges entered the New York market,

and in 1889 New York received its first carload of deciduous fruit

from California.

From these beginnings sprang the great refrigerator transportation

industry which brought revolutionary changes in the production

and distribution of fresh fruits and vegetables, meats, fish and

other perishables.

Railway refrigerator service broke down the barriers of distance.

Farming areas, remote from consuming centers, but especially adapted

by soil and climate to the production of certain fruits or vegetables,

could for the first time be developed commercially on a large

scale, with the entire country for their market.

By thus increasing the opportunities of the farm population

and making a wide variety of fresh foods available in all parts

of the country at all seasons of the year, the railroads contributed

to a higher standard of living, increased commercial activity

and increased industrial production throughout the nation.

All sections of the country benefited from these developments.

Because of refrigerator car service provided by the railroads,

Pacific Coast states can and do produce lettuce, cabbage, carrots,

celery, onions, asparagus, pears, grapefruit, cantaloupes, grapes,

peaches, plums, oranges apples, tomatoes, lemons and other fruits

and vegetables for the people of distant New England and all other

parts of the country, as well as the several provinces of Canada.

Oranges, grapefruit, tangerines, limes, lemons, peaches, strawberries,

watermelons, celery, spinach and tomatoes produced in Florida,

Louisiana, Texas, and other Southern states are marketed in nearly

every state in the Union as well as in Canada. Potatoes from Maine

and Idaho find their markets at points as far distant as Florida

and Texas.

In order to reach the consumer, potatoes travel an average

distance of 741 miles; peaches, 843 miles; cabbage, 970 miles.

Even greater travelers are the watermelons that come to our tables,

their average journey being 1,084 miles, and apples, which travel

1,162 miles on the average. And the berry family travels 1,200

miles, on the average; tomatoes, 1,894 miles; oranges and grapefruit,

2,126 miles; and cantaloupe and melons come 2,434 miles-about

as far as from Los Angeles to Cincinnati. But the record-holder

among domestic fruits is the grape. This little fellow journeys

2,597 miles to reach our tables!

Large cities, such as New York and Chicago, are almost wholly

dependent on distant points for their food supplies.

Of more than 35,000 carloads of fresh fruits and vegetables

received in Boston in 1939, 10,456, or 35 per cent, came from

California; 8,224 carloads, or 23 per cent, came from Florida,

and 1,925 carloads, or 6 per cent, came from Texas. Thus, approximately

two out of every three carloads came from these three distant

states.

Seventy per cent of the fruits and vegetables consumed in New

York City comes from points 1,000 miles or more away.

The widespread distribution of perishable products by rail

is shown by a study of receipts of fruits and vegetables at 66

principal marketing centers in the United States. The study shows

that 58 of these markets received peaches from Georgia, 59 received

celery from Florida, 37 received grapes from Arkansas, 48 received

tomatoes from Mississippi and 43 received strawberries from Louisiana.

Of 31,460 carloads of fruits and vegetables unloaded in Philadelphia

in a recent year, 10,295 came from Florida, 9,682 came from California,

2,185 came from Maine, 1,571 came from Texas, 1,060 came from

South Carolina, 993 came from New York State, 941 came from Arizona,

603 came from Idaho, 574 came from Washington State, 532 came

from Georgia, 517 came from North Carolina, and the remaining

2,507 carloads came from 26 other states. Thus, 37 out of 48 states

in the Union contributed to Philadelphia's supply of fruits and

vegetables.

Reports of the United States Department of Agriculture show

that Boston draws carload shipments of fruits and vegetables from

38 states; New York City from 41 states; Baltimore from 32 states;

Buffalo from 34 states; Pittsburgh from 41 states; Cleveland from

41 states; Cincinnati from 40 states; Detroit from 43 states;

Chicago from 42 states; Milwaukee from 39 states; St. Louis from

40 states; New Orleans from 38 states; Kansas City from 34 states;

Denver from 24 states; Salt Lake City from 12 states; and Los

Angeles from 12 states.

In a recent year, the railroads of the United States transported

394,000 carloads of fruits, 567,000 carloads of vegetables and

440,000 carloads of dairy and packing-house products. Many of

these commodities move under refrigeration; some move in specially

heated cars to prevent freezing; some move under controlled temperatures

without ice or heat.

To provide the American people with year-round, nation-wide

service in the transportation of perishable products, the railroads

operate a fleet of 145,000 refrigerator cars. Assembled in a single

train, these cars would reach 1,194 miles across the country.

Many refrigerator cars are owned by private car companies.

In cooperation with the railroads, these companies make advanced

studies of the transportation needs of the fruit and vegetable

producing regions and see that a sufficient number of empty refrigerator

cars are at the numerous loading points when they are needed.

Solid trainloads of fruits and vegetables are frequently shipped

from the producing areas at the height of the harvest season.

These trains move on fast schedules. For instance, strawberries

from the Carolinas reach New York for second morning delivery;

peaches from Georgia arrive in New York for third morning delivery;

strawberries from Louisiana arrive in Chicago for second morning

delivery. Trainloads of perishables from Florida, Texas, Pacific

Coast points and other areas are timed for delivery in Eastern

cities at a definite hour.

The refrigerator car is a long-distance traveler among freight

cars. Trips from California to Boston; from Florida to Minnesota

or Montana; or from South Texas to New York are not uncommon.

And as soon as it has been emptied, it hurries back to the producing

region, usually empty, for another load.

I've Been Working

on the Railroad | Contents Page

|