|

THE CENTURY MAGAZINE

VOL. LXXIV AUGUST, 1907 No. 4

THE GATES OF THE CITY

BY JESSE LYNCH WILLIAMS

WITH PICTURES BY ORSON LOWELL

I

IN the days when cities were surrounded by walls, all who would

enter or go forth were obliged to pass through the gates—usually

called "frowning portals" for the purposes of romance.

So it was no wonder that these places became popular and important

points not only in war, but in times of peace.

Here barterers and beggars would gather, soothsayers, story-tellers,

and many others who had business with those coming or going, including

not a few who had no business there at all except to look on.

That is why "the gates of the city" form a frequently

repeated background for the human drama all through ancient history

and literature.

Nowadays, to be sure, we have done away with walls for the

most part, but we have not increased the number of exits and entrances.

Proportionately they are more restricted than ever. The railroad

stations, with their wide-arched trainsheds, covered with dirty

glass, may be regarded as the modern city gates by those who get

a more satisfying interest out of things by reason of a resemblance

to something else. Similarly the ferries and bridges, with a little

more squinting of the eyes, may be looked upon as so many ancient

portcullises, if you like.

But the present point is that these are the places where humanity

(such as it is nowadays) may be seen passing in and out of the

city. And because our cities happen to be so much larger than

those of old, and every one in and out of them is more given to

travel, both for work and for fun, these portals are in a position

to frown, if so disposed, at the daily ebb and flow of multitudes

greater than the entire population of many a complacent ancient

capital. For here the paths of the world converge. Here meet people

of about all the kinds that there are, brought shoulder to shoulder

for a moment, as in a narrow mountain-pass, then scattering out

to the four winds of heaven, each traveler aiming at something

somewhere, and each in rather more of a hurry, no doubt, than

was the average ancient.

II

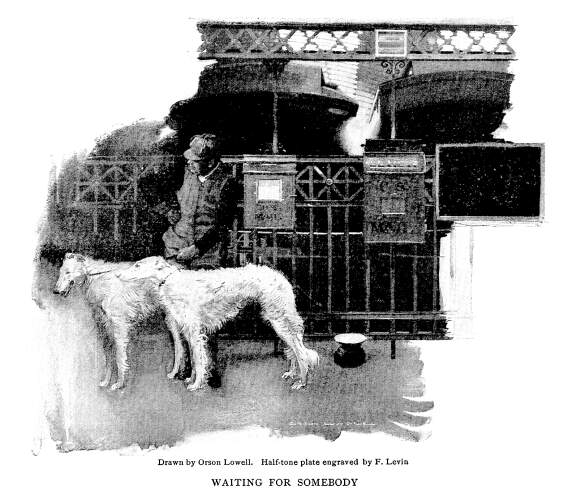

THESE huge, echoing, funnel-like

places, created by commerce merely for the coming and going of

so many impersonal units, take on a deeper significance to most

of the units themselves. For many they serve as memorable backgrounds

to the human emotions,—joy, grief, hope, disappointment,—all

crowded together into such cruel contrasts. The glad laughter

of reunion breaks in upon the uncontrolled sobbing of farewell.

The gay wedding party romps thoughtlessly by the slow-moving group

in black accompanying the white-pine box. Fashion glides through,

followed by a maid carrying her lap-dog; Poverty trudges along

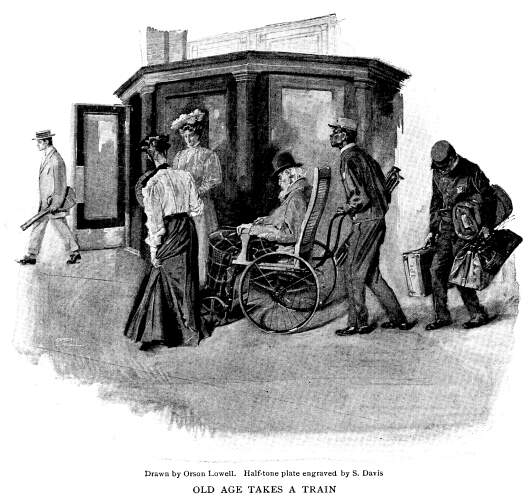

with no one to carry her wailing children. Athletes spring upon

the train, bound for country clubs; invalids are wheeled along

in chairs, bound for the sanatoriums. Youth is here, going home

from school; Old Age, going home to die. THESE huge, echoing, funnel-like

places, created by commerce merely for the coming and going of

so many impersonal units, take on a deeper significance to most

of the units themselves. For many they serve as memorable backgrounds

to the human emotions,—joy, grief, hope, disappointment,—all

crowded together into such cruel contrasts. The glad laughter

of reunion breaks in upon the uncontrolled sobbing of farewell.

The gay wedding party romps thoughtlessly by the slow-moving group

in black accompanying the white-pine box. Fashion glides through,

followed by a maid carrying her lap-dog; Poverty trudges along

with no one to carry her wailing children. Athletes spring upon

the train, bound for country clubs; invalids are wheeled along

in chairs, bound for the sanatoriums. Youth is here, going home

from school; Old Age, going home to die.

The gate-way of the city marks the beginning and end of many

things. Here the traditional young man from the country is confronted

by a confused view of the city he has come to conquer, though

at this moment, contrary to tradition, he is more likely to be

thinking about his baggage. Here again, after conquering, or being

conquered, he slowly retraces his youthful steps, to retire upon

his farm—or the county's.

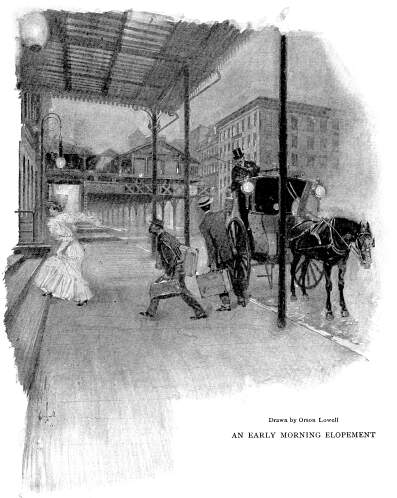

The station is a rendezvous for lovers and the means of flight

for the faithless. Here the city goes out into the fields to play,

and the country comes to the town to work. In the crowd are mothers

waiting for their sons, green-goods men waiting for their prey,

pickpockets watching for their chance, and detectives watching

for theirs. If we wait long enough, we can see nearly all the

world, coming in or going out, asking questions, answering them,

buying tickets, losing them, gazing or being gazed at—from

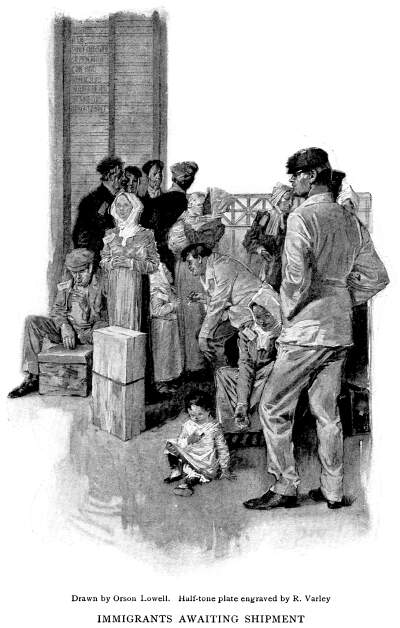

the Presidential party embarking upon a speechmaking tour, or

a foreign prince of the royal blood, to the herds of steerage

passengers being shunted like cattle into long immigrant trains,

or "fresh air" children returning to the noise and delight

of their beloved and begrimed city streets.

III

HISTORY is repeating itself, and

even America is becoming a nation of cities. When we began as

a nation,—in fact, as late as the beginning of the last century,

only four per cent. of the population was urban. At the time when

the nation's unity was threatened, all but sixteen per cent. were

still country people; now a third of us live in the city. HISTORY is repeating itself, and

even America is becoming a nation of cities. When we began as

a nation,—in fact, as late as the beginning of the last century,

only four per cent. of the population was urban. At the time when

the nation's unity was threatened, all but sixteen per cent. were

still country people; now a third of us live in the city.

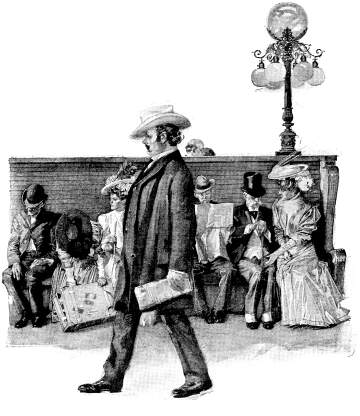

But along with this trend there is also a tendency to live

beyond the city walls. Those who come and go we call commuters,

and they are usually pictured as in a great hurry, carrying several

bundles. These make up the great bulk of the crowd that jostles

its way morning and evening through our city gates, predominating

all other types of travelers, unless perhaps it happens to be

a traveler of such an unusual sort as not to be a type at all—like

the peasant woman from the Balkans in long boots and a short plaid

skirt, or the Hindu maharajah, whose bright costume contrasts

with the dullness of his tired eyes as he bestows a benignant,

quizzical glance at the unreasoned haste of this restless young

nation.

Commuters acquire in time a similarity of expression as they

pass in and out through the gates. They have an air of accustomedness

to their surroundings, quite as if the station were their familiar

club. For that matter, many of them use it as such. When the inspiring

megaphone-man announces a train, they do not seem to be startled,

like the poor, panicky woman with the many babies and bundles.

The commuter is often in a hurry, but he is seldom flurried; he

nods to passing acquaintances, or keeps on reading the afternoon

paper, as he strides abstractedly through the iron gates, and

mounts the steps of the moving train with much the same assured

air of ownership as when he ascends his own porch, perhaps an

hour later, far away from the hurly-burly.

Nearly all of them wear this look of their type, though in

reality they are no more alike than the individuals of any other

army marching in unison and carrying knapsacks or newspapers.

The guard there at the gate, who has a ticket-punching acquaintance

with all of them, soon learns to distinguish the different varieties.

At the Grand Central Station, in New. York, the "substantial

banker" is likely to show "Greenwich" on his monthly

ticket, whereas the man behind, who is like him, but with less

substance, will probably go on to Stamford. Similarly the horsiest

and yachtiest commuters are apt to live in Larchmont, while those

not quite so pronounced get off at New Rochelle. Artists and literary

people are more frequently bound for Lawrence Park, Bronxville,

than for any other one place, while a variegated mob makes for

Mount Vernon. But of course even to these rules there are at least

enough exceptions to prove them.

The Human Medley in the Waiting-Room

Your true commuter must be by nature a man who takes to routine.

There are some who have commuted for a quarter century or more,

and yet have not acquired the trick, and never will. They are

the ones who write letters to the newspapers, airing their grievances

against the heartless railroad corporations. They are not born

commuters; they have had commutation thrust upon them. But many

really enjoy the life of the commuter. They like the clock-like

regularity. They like the pleasant social aspect of the early

morning trip to town, the neighborly interest in one another's

affairs, the ample time for reading the newspapers, which numerous

city residents miss by not being obliged to get an early start.

They look forward to the pleasant relaxation of the whist game

on the way home, with head on one side to keep the smoke out of

their eyes. Some of them even say that they enjoy being awakened

early in the morning.

In time, all who work in New York will come to it. Meanwhile,

for the man with a family it appears to be in many ways a happy

solution of a difficult problem. Undoubtedly it is a more wholesome

existence physically, but mentally and spiritually it has the

defects of its virtues when pursued all the year round.

The commuter devotes the best part of the day to one narrow

corner of the city; the rest of his time, not consumed on the

train, is in the still more narrowing atmosphere of the suburbs.

He neither gets all the way into the life of the city nor clean

out into the country. So his view of things has neither the perspective

of robust rurality nor the sophistication of a man in the city

and of it. His return to nature is only half-way; his urbanity

is suburbanity. Much of our literature, art, and especially criticism

shows the taint of the commuter's point of view.

IV

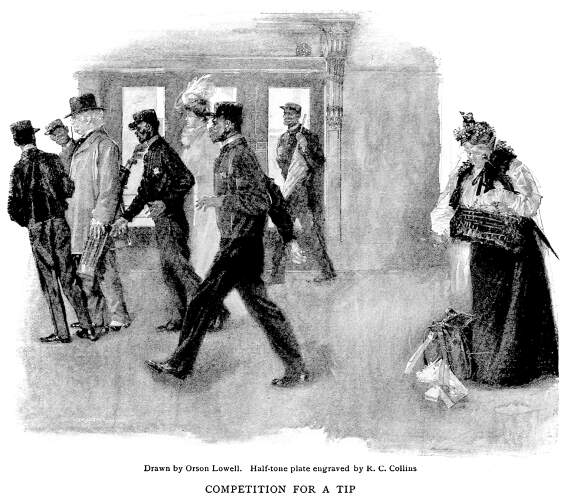

FOR many different sorts of people

the railroad station is more than a mere passage for going and

coming. The number of persons employed in every great terminal

is an army in itself, from the high officers in the unseen offices

overhead to the low officials in the cellar; from the general-manager,

looking out for dividends, to the uniformed porters, looking out

for tips—and showing rare insight in the selection of passengers

with a single hand-bag from the Pullman, while avoiding less likely

ones with bird-cages from the common coach. There are auditors

and the men who hammer the wheels of arriving cars; sellers of

food and sellers of flowers; train-despatchers and bootblacks;

floor-scrubbers and telegraph-operators; ticket-sellers and those

who pounce upon incoming trains, almost before they are emptied,

with long-handled window-cleaners, and with the hurried, businesslike

manner characteristic of all connected with the business of hurrying

people back and forth across the country. FOR many different sorts of people

the railroad station is more than a mere passage for going and

coming. The number of persons employed in every great terminal

is an army in itself, from the high officers in the unseen offices

overhead to the low officials in the cellar; from the general-manager,

looking out for dividends, to the uniformed porters, looking out

for tips—and showing rare insight in the selection of passengers

with a single hand-bag from the Pullman, while avoiding less likely

ones with bird-cages from the common coach. There are auditors

and the men who hammer the wheels of arriving cars; sellers of

food and sellers of flowers; train-despatchers and bootblacks;

floor-scrubbers and telegraph-operators; ticket-sellers and those

who pounce upon incoming trains, almost before they are emptied,

with long-handled window-cleaners, and with the hurried, businesslike

manner characteristic of all connected with the business of hurrying

people back and forth across the country.

The possibilities of the station as a sort of club are thoroughly

appreciated by the true commuter. When he has been up too late

the night before, playing bridge with the neighbors or gossiping

about other neighbors, he stops here for a hurried breakfast in

the morning. Some station restaurants are famous for their specialties.

When his wife joins him in town to go to the theater, he meets

her at the station. He can shave here, too, if he chooses, and

for five cents can even rent a place to dress in. If he forgets

his umbrella, he can lease one at the parcel-room. If it has cleared

off, he can check his cumbersome raincoat.

The parcel-room is one of the best institutions of this club.

Perhaps this explains why so many stations are called depots in

this country, though never in France. The parcel-room is a depot.

All sorts of things are sent there, marked by the commuter's name

and held until called for. The agent, of course, knows the commuter,

and often knows which is his wife, too, as well as the newsboy

knows which is his newspaper. When Mrs. Commuter comes in town

for a day's shopping, she telephones down to the office, from

the station, that certain very important things are to be sent

to the parcel-room, and that he must not forget this time to bring

them out with him. Only, at the Grand Central, they do not refer

to it as the parcel-room: it is called Mendel's. All the New York

shops know Mendel's, and it is unnecessary to give any further

address. At the close of any day you may see the familiar sight

of one or more of the rearguard of commuters—the kind who

never allow more than a fraction of a minute for the transit of

the station—rushing madly toward the corner where Mendel's

is situated. The agent sees them coming from afar, butting through

the crowd as the gong sounds outside by the gate. He reaches down

for their packages, holds them out over the counter, and the commuters

grab them on the run as the mail trains catch up the mail-sacks

at full speed, then squeeze through the gate just as it is slammed

shut by the ticket-puncher.

I know a man who used Mendel's

so often when a commuter that he can not break the habit now that

he lives in town. His bachelor apartment is on Gramercy Park,

he is occupied during the day at 49th street, and in the evening

he is very often occupied in one of the neighboring residence

streets. Rather than go all the twenty-odd blocks down to Gramercy

Park and back, it is his custom to bring his evening clothes in

a suit-case to Mendel's in the morning; then, at the close of

his day's work, he rents a dressing-room at the Grand Central.

This arrangement gives him so much more time to devote to the

evening, which is a great consideration just now. I know a man who used Mendel's

so often when a commuter that he can not break the habit now that

he lives in town. His bachelor apartment is on Gramercy Park,

he is occupied during the day at 49th street, and in the evening

he is very often occupied in one of the neighboring residence

streets. Rather than go all the twenty-odd blocks down to Gramercy

Park and back, it is his custom to bring his evening clothes in

a suit-case to Mendel's in the morning; then, at the close of

his day's work, he rents a dressing-room at the Grand Central.

This arrangement gives him so much more time to devote to the

evening, which is a great consideration just now.

"Over by the telephone-booths" is the place where

lovers meet. They pretend to be waiting for a telephone number

as they pace up and down with elaborate carelessness, which does

not even make the station attendants smile, they are so used to

it. There is a stand near-by where violets can be purchased leisurely

while waiting for the meeting, and there are plenty of doors and

corners to dodge in and out of should acquaintances appear. The

booths themselves are sometimes "commandeered" when

the necessities of love or war arise.

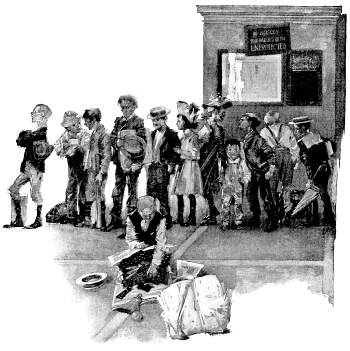

"Fresh-Air" Children Waiting for a Train

V

AT the Bureau of Information two men are kept busy from morning

until midnight answering questions in seven languages.

I once asked this one: "Do you get many fool questions

here?"

The man who speaks only American

looked as if he thought that was one. "Do we!" he replied.

"The other day somebody wanted to know how many ties there

were in the Poughkeepsie Bridge. Sometimes they ask how long the

Erie Canal is. Oh, yes, we get fool questions all right." The man who speaks only American

looked as if he thought that was one. "Do we!" he replied.

"The other day somebody wanted to know how many ties there

were in the Poughkeepsie Bridge. Sometimes they ask how long the

Erie Canal is. Oh, yes, we get fool questions all right."

Most of the inquiries are for timetables or railroad connections,

and the majority of them come in the afternoon and evening. Some

of them are somewhat remote, such as, "What is the best afternoon

train out of Sacramento for San Francisco?" or, "How

do you get to the Klondike?"

Many travelers, unused to the quick manner of these alert minds,

trained to answering questions, are apt to linger and blink and

ask it all over again, as if unconvinced that the reply could

be in earnest when given with so little thought. "Just as

if we had to think," commented this useful official, "to

answer questions we get fired at us a hundred times a day."

In addition to the questions over the counter, come questions

by mail and telegraph, beside the many that are put by telephone

over the two trunk lines and the two wires that connect with the

various departments of the building.

The megaphone-man stands up on an elevation like a pulpit,

with stairs leading down on each side of it, which helps the ecclesiastical

effect. For eight hours he stands there magnificently and tells

people that their trains are ready for them, then his voice is

relieved by the arrival of one or the other of his two confreres.

They work thus in eight-hour shifts all through the day and night

at the gates of the city, animated guideposts at the parting of

ways, as all men in pulpits should be.

In some station the announcement ends up with a stirring "All

aboard!" which makes one feel like taking that train whether

it is the right one or not. Some of these announcers are famous

the country over. There used to be one in Chicago some years ago

before the megaphone was a common household utensil, who pronounced

the names of the various stations with such wonderful resonance,

with such a compelling suggestion of the alluring possibilities

in the connections he mentioned, that it was almost as good as

a romance of travel and adventure just to listen to him.

But it is a very serious matter,

the dean of the Grand Central announcers assures me, and it isn't

every one can do it. And he offered to let me try if I did not

believe him. He declared, moreover, that he is obliged to expend

just as much effort now as in the old, dark, megaphoneless days.

It is all a great mistake to think it helps him, but the

public whom he serves is benefited because his voice now reaches

out to the uttermost recesses of the room. "Just put me up

there on one of those vestibules out in the shed," he declared,

warming up to the subject with proper professional pride, "and

I'll bet I could throw my voice clear out to the end if they'd

only keep their confounded engines quiet." But it is a very serious matter,

the dean of the Grand Central announcers assures me, and it isn't

every one can do it. And he offered to let me try if I did not

believe him. He declared, moreover, that he is obliged to expend

just as much effort now as in the old, dark, megaphoneless days.

It is all a great mistake to think it helps him, but the

public whom he serves is benefited because his voice now reaches

out to the uttermost recesses of the room. "Just put me up

there on one of those vestibules out in the shed," he declared,

warming up to the subject with proper professional pride, "and

I'll bet I could throw my voice clear out to the end if they'd

only keep their confounded engines quiet."

The dignified deliberation of his utterances had always impressed

me deeply. His explanation of this, however, has made clear that

his manner was not due to the vain-glorying of one in a high calling.

I had ventured to ask him about his rhetorical pauses. "Why

do I say 'Track—number—eighteen?' Because if I said

'Track number eighteen,' the way you talk, those people you see

'way down there by the Pullman office would only get something

like 'Ac-clack-teen-clack.' You have to know how, in order to

do this thing right. After I say 'number' I wait till the echo

brings it back to me before I say 'eighteen.'

"Even then, you see," he added, shrugging his shoulders

after an interruption caused by a woman carrying a baby up the

steps toward him timidly as if about to offer a sacrifice—"even

as it is, you see they come up here and bother me with questions

as if I was only a bureau of information. What? Oh, yes, she heard

me, but she just wanted me to say it all over again for her specially—sort

of whisper it to her confidentially. That's because she's a woman,"

he added, with the calm tolerance of a philosopher looking down

upon the passing, fretful world from a superior height. Then he

raised the mighty megaphone to his lips to announce another train.

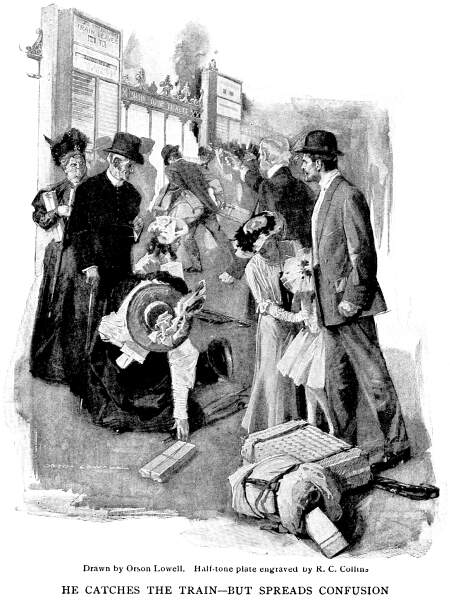

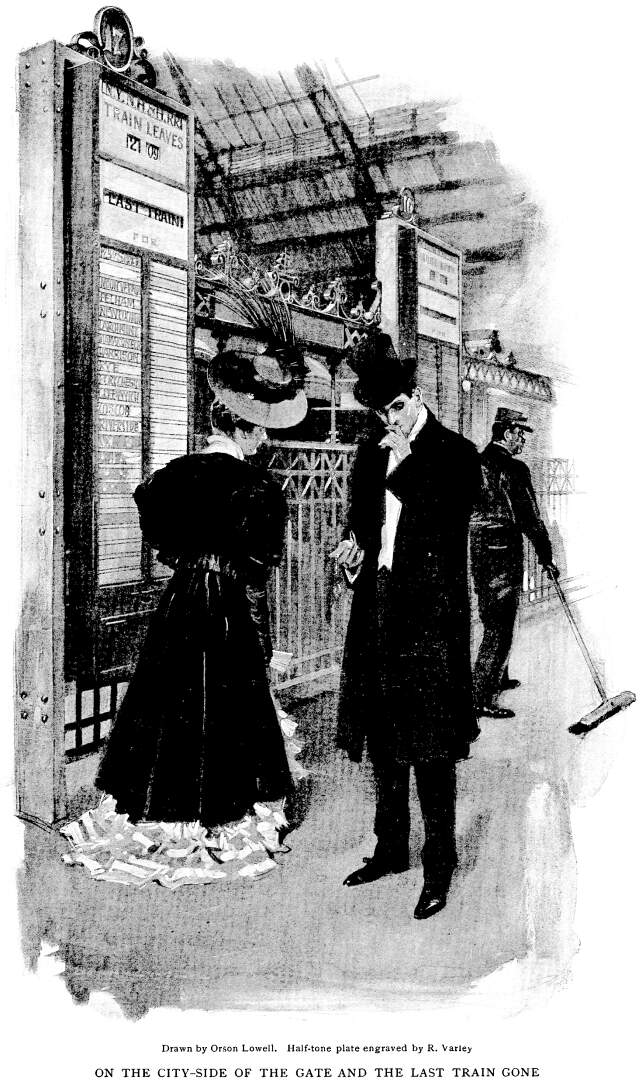

Every evening there is something of a scramble for the 11:57

or the 12:03 or whatever may happen to be "the last train"

out, up, down, or over for the suburbanites that live in those

directions. Theater-parties come scurrying through, close upon

one another's heels, the men, with overcoats buttoned up to their

chins, striding ahead and fumbling for tickets, the women, holding

on to their hats, their high heels clicking on the mosaic floors

as they make haste in the interesting feminine way, arousing the

sleepy ones waiting for an early morning express.

Once the haven of the open gate is reached, they slow up for

breath, and have something to laugh about half-way through the

long, dreary anticlimax of their evening's entertainment. But

almost every night certain ones are excluded from among the blessed,

for the man in brass buttons at the gate is as impartial as St.

Peter. A tantalizing feature of this is the dramatic pause ordained

between the inexorable clanging of the gates and the slow, deliberate

starting of the unobtainable train, while those kept out stand

with their faces pressed against the bars, like prisoners looking,

for a moment, as if they meant to bite their way through. When

this thing happens to a solitary couple, unmarried, unchaperoned,

and unacquainted in the midnight city, it is a tragic moment as

they turn and look at each other, wondering what to do about it.

The Lost and Found Department ought

to furnish interesting data for psychologists, and for moralists,

too. The absent-mindedness of travelers gives employment to two

busy men at the Grand Central Station. Whatever is picked up in

the trains is brought in to them, or is supposed to be; and a

surprisingly large percentage of what is found is actually brought

in. It includes all sorts of stuff, from stickpins to packages

of bonds. A great many things are claimed, identified, and recovered

almost immediately, so that not all that's lost and found is recorded

on the books. But even so, on the Saturday when a certain inquiry

was made, the clerk reported no fewer than 107 articles for that

one week. This included none of the harvest gleaned from the parlor

and sleeping cars, for the Pullman Company has a Lost and Found

Department of its own. The Lost and Found Department ought

to furnish interesting data for psychologists, and for moralists,

too. The absent-mindedness of travelers gives employment to two

busy men at the Grand Central Station. Whatever is picked up in

the trains is brought in to them, or is supposed to be; and a

surprisingly large percentage of what is found is actually brought

in. It includes all sorts of stuff, from stickpins to packages

of bonds. A great many things are claimed, identified, and recovered

almost immediately, so that not all that's lost and found is recorded

on the books. But even so, on the Saturday when a certain inquiry

was made, the clerk reported no fewer than 107 articles for that

one week. This included none of the harvest gleaned from the parlor

and sleeping cars, for the Pullman Company has a Lost and Found

Department of its own.

Odd human traits are disclosed in the strange adventures of

some lost articles. If the articles themselves could only tell

of their experiences, we might know more about the traits. Occasionally

a jewel or something else of considerable value will be reported

as lost, and will be inquired for day after day in vain. Then

suddenly, sometimes after an interval of weeks, the missing property

will turn up at the Lost and Found Department, often in such a

manner as to preclude the acceptance of a reward. These are called

"conscience" cases by the, clerks, and they get a great

many of them. One day a certain artist, perhaps because he is

an artist, absentmindedly left a valise in the train. It contained

money, household silver, and two bananas. Some time after he had

given it up for lost, it came back. Opening it, he found everything

there except the bananas. Perhaps the finder decided that he was

entitled to that much for carrying such a heavy load in his hand

or on his conscience so long. Perhaps he had a wife who thought

that the bananas would rot and tarnish the silver.

VI

In every station one may find those who do not take trains

or meet them, nor attend those who do. Some come to the waiting-room

only to wait—respectable derelicts still hoping that something

will turn up, and wrecks who have given up hope. It is a warm

place in winter, the seats are comfortable, and thoughtless passengers

often obligingly leave newspapers behind them. It makes good waiting.

There are so few other places to wait—so cruelly few for

women adrift, but not yet foundered. Sometimes, to deceive that

meddlesome busybody, the station detective, they carry in traveling

bags, and pretend to be pulled down with their burdens, emptied

long since at the pawn shops.

In the case of the men, one might find out their story, if

one cared to; but as for the women,—the shabby little old

lady with the corkscrew ringlets, for instance,—is she, like

Eli in the Scriptural tragedy, watching at the city gates for

sons who will never come back? Or is it a lover she thinks of

as she sits there all day, waiting and waiting? We can only wonder,

and try to forget, as we go on our way.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|