|

THE GHOST OF A TRAMP.—Frank Leslie's-April 2, 1881

IT WAS on my way from New York to Pittsburgh, by way of the

Pennsylvania Railroad, and was lounging in my chair, lazily watching

the beautiful blue Juniata as the train sped along the river-bank.

It was a Summer evening, and the sun was sinking slowly behind

the Western hills, as it it were loath to leave the scene of so

much beauty. Floods of glorious golden light came pouring down

upon the landscape, and the river, as if unwilling to be outdone

in effulgence, gathered the burning rays in its broad bosom, and

flashed them back to the sun in a blaze of splendor.

As the train rolled on, its iron path gradually led it to the

mountain-side, and at last it burst into that charming valley

known as the Lewistown Narrows. It was a scene of surprising loveliness

and awful grandeur. The river blazed and sparkled, and glowed

and dimpled, by turns, in response to each parting kiss from the

sun but even the caresses of that luminary were not sufficient

to stay its course, for it hastened on its appointed journey,

now rustling furiously at the gray old rocks that had held their

defiant heads above the surface for centuries; now embracing amorously

some jutting cape, which, bolder than the rest, had extended itself

into the stream; now roaring, gurgling, foaming, as it tumbled

over tile inexorable rocks; now smiling, sparkling, whispering,

as it kisses the verdure on the banks. But, faithful to the end,

it penetrates all barriers, and finally merges into a beautiful

stream, which stretches away to the east as far as the eye can

reach.

The mountain rises loftily above the river, and bears suspended

on its side the railroad and the, rushing train. Here it presents

to the eye the appearance of a broad, forest clad plain, stretching

obliquely from the earth to the skies; there it is a mass of granite,

piled upon a larger mass, whose frowning aspect is unrelieved

by a single tree. There, on the sister mountain, which rises almost

perpendicularly on the opposite side of the river, midway up its

steep ascent, a huge rock bangs threateningly over its base, and

from its commanding portion one could easily imagine that it had

originally been wrenched from its bed by some powerful convulsion

of Nature and hurled down tire steep incline; but, having had

time in its mad rush to see the surpassing loveliness of the valley,

it had stopped suddenly half-way down, and remained there ever

since. So I imagined, as I caught a glimpse of the charming scene

through the car window. The train was moving toward the west in

the face of the sun, now nearly set, but I could see the wondrous

beauty of the sky from my chair. Steadily the great eye of day

withdrew, and finally, after a longing, lingering look, it disappeared.

A perceptible change now came over the landscape. The dazzling

brilliancy of the sun gave place to a mellow light, which rested

lovingly upon the water and the mountain sides. The shadows deepened

as the wondrous panorama went on, and the foliage assumed a darker

hue.

Overhead the sky was softly tinted with the red and green which

streamed out from the west, and the few clouds which gracefully

draped the resting-place of the lord of day were pierced through

and through, and yet bolted together by many fiery streaks of

shining gold.

All who gazed upon this splendor felt its wondrous power over

the human heart.

Scarcely a word was spoken. All were absorbed in contemplation

of the ineffable grandeur of the dying sun.

Suddenly the spell was broken. A short, sharp whistle from

the engine pierced the ear, and each passenger, thus quickly recalled

to mundane affairs, grasped his chair and braced himself for a

shock.

Then came

a peculiar rubbing noise and a slight jarring sensation which

assured the frightened travelers that the famed Mr. Westinghouse

had, through the instrumentality of his air-brakes, clutched the

car-wheels with a death-like grip, and was endeavoring to stop

the train. A moment of dreadful expectancy ensued, and then, as

the train was quickly stopped, the trembling passengers perceived

that they were safe. Then came

a peculiar rubbing noise and a slight jarring sensation which

assured the frightened travelers that the famed Mr. Westinghouse

had, through the instrumentality of his air-brakes, clutched the

car-wheels with a death-like grip, and was endeavoring to stop

the train. A moment of dreadful expectancy ensued, and then, as

the train was quickly stopped, the trembling passengers perceived

that they were safe.

Of course, every one wanted to know the cause of the sudden

stoppage. Happily for the anxious travelers, the conductor now

appeared, and as he hastened through the car on his way to the

rear platform, be was beset by eager questioners.

A short reply was vouchsafed. The engine had struck a man.

Three short blasts of the whistle followed, and the train slowly

backed down the track. Only a few rods were traversed before the

signal to stop was given. I looked out the window, and saw lying

amongst the bushes a black object, which was readily recognized

as a human form.

The train continued to move until the baggage-car came opposite

to the body, when it stopped. Together with several passengers

I stepped out of the car and approached the ghastly figure.

The trainmen had already gathered about it, and one man—the

conductor—was turning the head around so as to expose the

face.

"Is he dead?" asked one of the passengers, in a low

voice.

"Dead!" said a man who was kneeling by the side of

the body—dead! Well, I should may so! I don't believe he

drew a breath after the engine struck him. Don't you see his head

is all smashed in? If there is a bone in his body that ain't broke,

then it ain't the fault of the engine."

I turned to look at the engine as it stood hissing and foaming

near the spot where it had just dashed the life out of a human

being, and I shuddered involuntarily as I saw the fireman, pour

a bucket of water over the pilot, and carelessly wash away the

blood and brains and hair with which the front of the locomotive

was bespattered.

At this moment the safety-valve lifted, and a cloud of steam leaped

into the air with a deafening noise, effectually precluding all

further attempts at conversation. Casting one look at the horrible

mass of quivering flesh which the trainmen were lifting into the

baggage-car, I returned to my seat in the Pullman, sick with horror,

and with nerves unstrung.

To be sure, it was only a man killed. Nearly everyday of my

life I had noticed a two or three-line paragraph in my newspaper,

announcing to the busy world that, another man had been, ran over

and killed on the railroad; but I rarely gave it a moment's thought.

It was only another death—and surely deaths were not so

uncommon as to call for a particular remark. But now I saw one

face to face, and not as in a glass, darkly, and I felt as if

a new world of thought had been suddenly disclosed to me.

Civilized men cannot bear to see the human body treated with

indignity. They likewise cannot bear to see human life ruthlessly

sacrificed. It has taken thousands of years to elevate men to

this height; but now that they have reached it, they see that

they owe their present high state of civilization to the respect

with which human beings are now treated.

Love and admiration for mankind elevate men above the savages.

The ancient Greeks thought so highly of men that they ascribed

human bodies to their gods, and sought to represent the divine

persons by means of statues.

Christianity would have failed had it not been that Christ

was a God in a human body. His presence in the flesh dignified

it, and has caused the human race to look upon their fellow-men

with increased respect, knowing that the human body is indeed

a "temple where a god may dwell."

The above thoughts passed through my mind as the train proceeded

on the journey which had been so fatally interrupted. It was soon

running at full speed, only to stop again at a small station at

which the conductor had determined to leave the body.

This caused a delay of a few minutes, but the time lost was

quickly regained after the train started, for in a very short

time we were rolling over the rails at the rate of forty-five

miles an hour.

In the meantime darkness had fallen upon the earth, and vailed

the beauties of the landscape from my eyes. The lamps were now

lighted, and they shed a soft, mellow light upon the interior

of the car.

It was certainly a charming conveyance—this Pullman parlor

I but I felt uncomfortable. Wherever I looked I saw in imagination

the pale, still face of that poor wretch, who had been hurled

so suddenly out of the world. Had he a wife somewhere, eagerly

watching for his return, and anxiously asking, like the mother

of Sisera, "Why is he so long in coming?" Had he children

and a happy home, or was he an outcast, a pariah, a tramp, only

a pauper whom nobody owns"?

My questions found no answer however, and I soon discovered

that, try what I would, thoughts of the fatal event would flash

through my mind, and, like Banquo's ghost, would not down. Wearied

at last of my thoughts, I arose and left the luxurious parlor-car,

and wended my way through the long train to the smoking-car. Here,

thought I, I can at least enjoy a cigar and, perhaps, the fumes

of the fragrant weed will wait away the visions I had conjured

up of a home bereaved. So thinking, I looked about me for a seat,

and, having found one. I sat down by the side of a nice-looking

man, who was just finishing a cigar. As I drew out my case and

selected a cigar, he courteously offered me his own to light mine

by. I accepted it gratefully, and, being unwilling to be outdone

in politeness, I offered him my cigar-case with an invitation

to help himself. He did so, and in a moment we were both puffing

away at our respective weeds. I now looked at my companion more

closely, and discovered that he was a man who could bear examination.

There was something In his manner that aroused my curiosity, for

I thought I could detect in him the air of a man who was accustomed

to danger. Be was apparently not more than forty years old, broad-shouldered,

keen-eyed, and dressed like a well-to-do mechanic.

Satisfied as to his character, I began a conversation by addressing

him as follows:

"That was a very sad accident, wasn't it?"

"Yes, indeed; it was an awful thing. But it was not an

uncommon event."

"No," said I, "it is not uncommon. Somebody

is ran over and killed nearly every day."

"It is hard on the engineer," said he, "particularly

if the victim be the father of a family."

"Yes," replied I, as a sudden light dawned upon me,

it must be hard on him. But are yon not a railroad man yourself?"

"Yes," said he with a quick look at me. "I am

a locomotive engineer myself. What made you suspect that?"

"Why," said I, in some embarrassment. "I fancied

it from your manner, for one thing; besides, you have the appearance

of a man who is accustomed to danger."

"I understand." he remarked, slowly. "You can

nearly always tell what a man is from his face."

"Do you run on this road?" I inquired.

"No, not on this road; but I am employed by the same company.

I run on a branch road of the New Jersey division. I am going

to Altoona now as a delegate to the convention of engineers. The

Brotherhood, you know," said he.

"Ah, yes! You represent your friends on a New Jersey road.

I presume you know from experience just how an engineer feels

when he runs over a man?" questioned I.

"Yes," replied he, reluctantly, I thought. "I

know what it is. I would rather lose a month's pay than run over

even a man's arm. You see, you can't forget it, no matter how

hard you may try. Once I struck a man near Milltown and killed

him. For a long time after that I never could pass that place

without shuddering, for I imagined that I could see the white,

ghastly face rise up out of the ground and turn its stony eyes

full upon me. But, then, that was an exceptional case. Perhaps

you read of it in the newspapers?" continued he, interrogatively.

"No," said I, removing the cigar from my mouth, do

not think so. At least, I do not remember it!"

"If, you had read of it you would certainly remember it.

It was very strange thing indeed. My engine struck a tramp and

killed him, you know. Well, a half-hour afterward the train was

saved from destruction by that tramp's ghost."

"By a ghost!" ejaculated I, in surprise. "Why,

you don't look like a men who believes in ghosts."

"I don't say that I do," replied he, with a twinkle

in his eye. "However, I shall always stick to it that my

train was saved from destruction that night by the ghost of a

tramp."

"Do you mind to in me the story?" asked I, prompted

by all the curiosity of my nature.

"I don't mind telling you the story, but I don't often tell

it."

"Come, now, let me hear It. I just feel like listening

to a good story, particularly if it has a ghost in it."

"I am afraid the ghost will disappoint you; still I will

tell it to you. It occurred two years ago, on the Belleview Railroad.

I ran an express-train from Lamberton to Belleview, and back again

the same day, being a round trip of a little more than a hundred

miles. My train left Lamberton, where I live, at one o'clock in

the afternoon, and reached Belleview about a quarter to three.

On the return trip I left the latter place at 7:30 p.m., and reached

home at nine o'clock. It was a very nice run, you see. Well, sir,

one day last Fall a year ago, I left home feeling very uneasy

about my wife. You must understand, sir, that we were expecting

a baby about that time, and Lucy kept saying over and over again

that she was sure to die and leave the little one all alone in

the world. Of course, that thing worried me considerably, for

I was very fond of Lucy, but I tried to cheer her up by telling

her that, since she had gone through with it before, she stood

a good chance of having an easy time of it now. But no, she wouldn't

be convinced. She felt sure that a shadow was hanging over us—those

are her words, sir, not mine—and it was about to fall and

cover us all with the darkness of grief.

"Well, I went away that day feeling very uneasy; and it

was no wonder I felt blue, considering the weather. Why, sir,

it had been raining steadily for three days, and the air was as

damp and chilly as it could be. The leaves were nearly all gone

from the trees, and everything had assumed that cold, cheerless

aspect which is peculiar to November. Well, sir, I climbed aboard

the old lady—that's my engine, you know, sir, although I

sometimes call her 'Susie'—496, sir, that's her number. Well,

sir, I got on her, and pulled out of the house, feeling pretty

gloomy. Then, besides, the train from Philadelphia was late, and

I had to wait fifteen minutes, which made me feel mad. However,

we got off at last, and inside of half an hour 'Susie' foamed

over. Do you know what that is?"

Upon my replying in the negative, he endeavored to explain

how the water in the boiler would sometimes boil so violently

as to fill the space intended for steam with foam, which would

work down into the cylinders and interfere with the stroke of

the piston.

"As soon as I found that out, I foamed over, too. It's

no joke to run a foaming engine when you are already behind time,

I tell you. But, you see, sir, I got the old lady all right directly,

and in a short time she was skimming along the metals at the rate

of two miles in three minutes, which was faster than the schedule

time. My train only stopped four times on the way up, so I succeeded

in gaining a little, but the devil himself seemed to have a hand

in managing our train that day, for when we got within five miles

of Belleview I saw a red flag ahead. I put on the brakes and stopped

suddenly, for, owing to the storm, I had not seen the flag until

I was almost up to it. The flagman told me that a freight train

was off the track right ahead, and that I was to wait until the

rails were cleared. And, sir, we had to wait there for an hour

before we could get past. Finally, we went on and reached the

station.

"The rest of that afternoon I spent in misery. I was worried

about my wife, for one thing, and for some reason or other I couldn't

get warm. I was chilled through and through by that damp, raw

November air, and, sir, if there ever was a man all in the downs

with the bluest kind of blue devils, it was myself.

"Well, time went on, and at 7:30 p.m. sharp I pulled the

throttle of Engine 496, and, picking up her train, sir, she swept

out of the station like a lady leaving the ballroom.

"It was still raining, and I could not see very far. I

don't know when I felt as nervous as I did that night. Yes see,

sir, several things combined to make me so. Besides being in the

blues myself, there was the fear that my wife might even then

be dying, and also I was a little worried about the condition

of the track.

The road ran right along the river bank, and I couldn't see

that, owing to the heavy rains, the river had risen at least ten

feet above low-water mark. On the other side of the track was

a long line of hills which stretched nearly all the way from Belleview

to Lamberton and I was very much afraid that the storm would cause

landslides.

"Then, again, there were at various points along the line

little streams which emptied into the river. Over these streams

the road was carried on culverts, which were large enough in the

dry season, but when the heavy storms caused the creeks to swell

to five or six times their proper size, the Culverts were too

small to allow the flood to pass through, and the result was that

the water collected behind the railroad and formed quite a pond,

which was prevented from joining the river only by the railway

embankment.

"Still, I had to make time. I kept a sharp lookout for dangers

ahead, but I could not see far. The storm blinded the light flung

out in advance by the headlight, and the rain-drops clouded the

glass in front of the cab, so it was very little use for me to

keep straining my eyes. However, I did the best I could and left

the rest to God..

"Everything went smoothly for an hour, only I steadily

lost time, for it wasn't human nature to rush on through the darkness

blindfolded.

"I had now reached Landsdale, where a my train stopped.

At this point we passed the up-train. It was somewhat behind time,

and I asked the engineer about the state of the track.

"'It's all right,' said he, I only I advise you to run

slow over the culvert below Milltown.'

"I didn't have time to ask more questions, for the bell

rang to start. I let on steam and pulled out rather lively, for

there was a fine piece of track just below the station, and I

knew that it was safe. It was about twenty miles from Landsdale

to Lamberton, and twelve miles to the culvert before spoken of,

and so I determined to risk the rate of a mile in two minutes.

The engine was just then in fine trim, having a high-water level

and making steam rapidly, and she made five miles in a trifle

less than ten minutes.

"So far, nothing had happened. We were now only fifteen

miles from Lamberton, and for the next two miles the track was

laid on a solid rock foundation, at least two hundred yards from

the river. Believing that accident was improbable on this tangent,

I gave the throttle another jerk, and the engine jumped forward

like a racer.

"For about ten minutes I sat there like a statue, with

both hands on the lever. The engine quivered like a leaf as she

danced over the joints of the rails, and hurled herself through

the darkness as if she, too, were anxious to get home.

"Presently I saw, the lights of Milltown appear in the distance.

As this was a small village, my train was not scheduled to stop,

and so I did not slacken up, but contented myself with ringing

the bell. "'It chanced that the road was slightly down-grade,

at this point—hence the speed of tile train was increased

a little.

"On we dashed up to the station, and were just passing

by, when I beheld a sight that fairly froze my heart's blood.

It lasted only a second, but even that brief space of time served

to photograph it on my mind forever.

Directly in front of the engine, distant only a few feet from

where I sat, a human face grinned at me. And such a face! There

was something indescribably horrible about it, and, in spite of

myself, I screamed right out. You can't imagine, sir, what a fearful

sight it was. You see, it just seemed to flash right out at me

and then disappeared. It was fully ten feet above the ground,

and directly in line with my face. The eyes were wide open, and

they glared at me terribly. The mouth, too, was open, and the

teeth were exposed; but, worst of all sir, right on the forehead

was a gaping wound, and the blood was apparently flowing from

it.

"All this I saw in a single second; it might possibly

have been even less. However, I was paralyzed with horror by it,

and it was half a minute before I recovered my senses. I quickly

closed the throttle-valve and applied the brakes. After I had

done this the thought flashed through my mind that I might have

been mistaken; that, owing to the troubles pressing on my mind

I might have imagined that which I thought was real. Then, again,

I thought it might have been a ghost; for you must understand

that, while I had never previous to this time believed in unearthly

visitors, I was scared enough then to believe in anything.

"But the train came to a dead stop,

"'What's up,' asked Tom Ryan, my fireman. 'What did you

holler for?'

"'Don't ask me, said I. 'Heaven alone knows what that thing

was.'

"I did not wait for any more questions to be put, but

jumped down from the engine and walked quickly to the pilot. I

had a torch with me, and by its light I examined the front of

the engine. Strange to relate, I saw no signs to indicate that

the engine had struck a man.

"At this juncture the conductor came up to learn the cause

of the stoppage.

"For a moment I knew not what to say. I was satisfied

in my own mind that the engine had not struck a man, because the

face I saw was that of a corpse, blanched and rigid. Besides,

I could not conceive how the engine could have tossed a man in

that strange position without the body falling back on the pilot.

But there was no evidence of having struck a man on the front

of the engine, and so I did not know what to say.

"'What is the matter?" asked the conductor; did you

run over somebody ?'

"'I don't know,' said I; 'I saw something like a dead

man's face right ahead, and so I stopped.'

"'A dead man's face!" said he, in surprise.

"'Yes,' said I, 'a dead man's lace. I'll swear to it in

any court of justice.'

"'You must have hit a man and tossed him into the air

just in front of the headlight, and you saw the light flash on

his face,' suggested tire conductor, after a pause.

"'Where is the body?' asked I.

"'We must look for it,' said he, and he sent out all the

trainmen, except the rear brakeman, to search the track. Several

men who were at the depot assisted them in the search, but they

seemed to put little confidence in my story.

"Well, sir, for ten minutes they wandered up and down

in all that rain looking for the body. I climbed into the cab

and staid there, feeling satisfied that there was no body. Yes,

sir, I honestly believed I had seen a ghost. I thought that it

had appeared to me to warn me of my wife's death, so, of course,

there was no use for me to hunt for a body.

"At last the conductor got impatient.

"'You must have been dreaming, Jack Thorn1ey,' said he;

'there is no body here.'

"'No, I wasn't dreaming,' said I; 'I'll swear I saw a face

right ahead.'

"'Call in the hind brakeman,' said he; 'we can't "stay

here all night.'

"Well, sir, I whistled four times, and in few minutes

the brakeman returned. The bell rang to go ahead, and I let on

steam. 'Susie' made about three revolutions of her drivers, and

then I stopped her.

"'Did you hear that noise?' I asked I of the fireman.

"'No. What noise?' questioned he.

"I made no reply. I heard the shout of a man directly

ahead, and something warned me to stop.

"I leaned out of the window and listened.

"I heard a shrill cry very distinctly. Involuntarily I shuddered,

and drew in my head.

"'There,' said Tom—'I heard that.'

"Again the cry was repeated. This time I thought I could

distinguish the word:

"'Stop!'

"'What on earth is the matter with you, Jack Thornley?'

asked the conductor, who had again come to the engine.

"'Listen!' said I." Don't you hear?'

"At that moment the cry once more rang out:

'Stop, stop—for God's sake, stop!'

"We three man turned and looked sit each other.

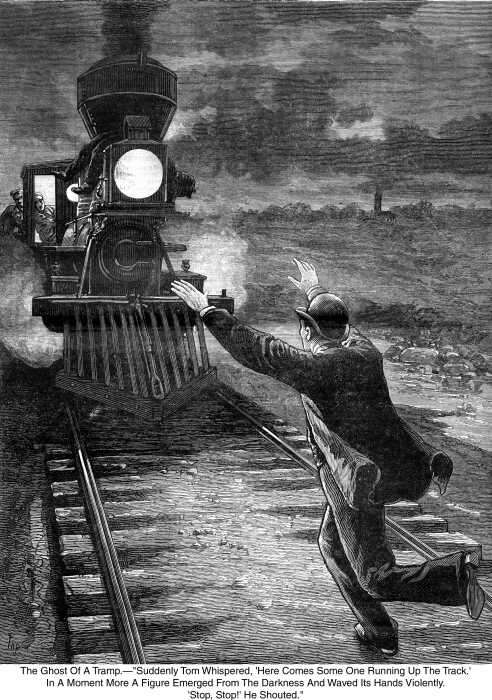

Suddenly Tom whispered:

"'Here comes some one running up the track.'

"In a moment more a figure emerged from the darkness,

and waved its arms violently.

"'Stop, stop!' he Shouted.

"'The train is not moving!' shouted I, in return.

"'The culvert! the culvert!' gasped he, as he staggered

up to the engine. 'It has caved in, and the track is washed away!'

"' The track washed away! Ah!' thought I, 'I understand

it now. My wife is dead, and her spirit appeared in front of the

engine to warn me of approaching danger.'

"To be sure, the ghost had a man's face; but you see,

sir, I was so scared by our narrow escape that I scarcely knew

what I thought.

"Well, Sir, I won't tire you out by making the story too

long. The rest can be told in a few words. It seemed that the

water had accumulated behind the embankment until it was powerful

enough to make a crevasse. As soon as this was done, the entire

embankment rapidly disintegrated, and was swept away into the

river. A man living near by saw the disaster, and knowing that

a train was due, he ran up the track to stop it.

"However, as he had no lantern, his attempt would have

been in vain; but fortunately, thanks to that ghost, I had already

stopped the train, and the fifteen minutes we spent in looking

for the body gave him time to reach us. That is all."

"But the ghost," said I—"the ghost, Mr.

Thornley. How do you account for that?"

"Well," said he, with a peculiar smile, "this

is the truth of the matter. Of course, since the track was washed

away, the train could not go on. The conductor telegraphed the

news to Lamberton, and he was ordered to remain at Milltown overnight.

So I backed slowly up to the station, and the engine came to a

stop right by a large reflecting-lamp at the lower end of the

station.

"Just as I stopped the train, a cry of horror arose from

the men on the platform. I looked at them and saw that they were

staring at the front of the engine. My eyes naturally turned in

the same direction, and, sir, I saw by the blaze of the depot-lamp,

a corpse tightly wedged in between the smoke-stack and the headlight

of the engine—a corpse, sir, and the face was turned toward

me. I understood it all then. There had been no ghost at all.

What I saw was the face of that dead man which was suddenly illuminated

by the depot-lamp as the train rushed by."

"But how did the corpse get there!" asked I, in amazement.

"I can't say for certain," replied he, since I did

not see the occurrence. An examination of the body revealed the

fact that he had been dead for some time—possibly half an

hour. His clothes indicated that he was a tramp, and I presume

the accident happened this way: The night was so dark that it

was impossible for me to see any distance ahead; so I am inclined

to think that the tramp was walking along the track when the engine

struck him. As the train was moving quite fast, the poor tallow

was knocked high in the air, and it chanced that the body fell

in between the smoke-stack and the headlight, where it remained

for half an hour tightly wedged in. The face was turned toward

me, and as the train passed the Milltown station, the large lamp

there flashed for a single second upon the face, and I just caught

a glimpse of it. Well, Sir, when I reached home next day, I found

my family increased by the arrival of a very young boy; and, sir,

he was born about the time when I first caught sight of the ghost

of a tramp."

"And how about your wife—was she dead?"

"Oh, no, sir, she wasn't dead. She is alive and well to-day."

"That is one of the strangest stories I ever heard,"

remarked I, as I threw away the stump of my cigar.

"It is true, sir, every word of it," said he, quietly.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|