The Yakima Raid and the

Coal Famine

The Pacific Monthly—March, 1907

By Lute Pease

"If the railways are trying to give the people an 'object

lesson,'" remarked the prominent citizen, "why I guess

Yakima can establish a little kindergarten for the railways."

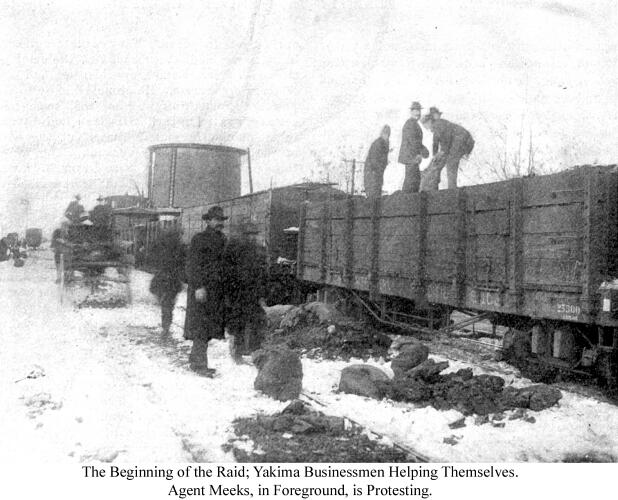

And next day North Yakima, Washington, sallied forth, held

up and confiscated a long trainload of Northern Pacific coal—and

paid for about one-third of it.

The railway's monetary loss is regarded lightly by some of

the citizens. "It's a small fine for the company's neglect

and general cussedness," but the city's honorable business

men regret the moral effect of this feature of the historic raid,

and its results to the reputation of the town.

It is not the purpose of this article to throw more bricks

at the railways, though it may shy a peanut shell or two at both

sides. But the story of the picturesque episode and its causes

is interesting and rather instructive.

North Yakima is one of the finest types of Northwestern towns.

It was built by irrigation. Seventeen years ago most of its site

and the wide sweep of surrounding valley was sagebrush and bunchgrass.

Then came the Sunnyside ditch (a Northern Pacific enterprise),

which spread a portion of the waters of the Yakima over many thousands

of acres of "volcanic ash" soil—richest and deepest

in the country. Settlers were invited to come in and take up tracts

of ten acres, and upwards, on long time and easy payments. They

came, and soon the desert vanished. In its place bloomed apple,

peach and prune orchards, wonderful fields of alfalfa and record-breaking

crops of the finest potatoes in the world.

The town,

at first a "wide open" frontier hamlet, rapidly developed

into the present-day beautiful city of 10,000 inhabitants, splendid

schools, high license, Carnegie library, numerous prosperous banks,

good hotels, substantial mercantile houses and fine church structures.

Its wide streets, excellent light and water systems, well-edited

daily newspapers and other advantages, are also the pride of its

people and of the agricultural population of some 15,000 tributary

to it. The town,

at first a "wide open" frontier hamlet, rapidly developed

into the present-day beautiful city of 10,000 inhabitants, splendid

schools, high license, Carnegie library, numerous prosperous banks,

good hotels, substantial mercantile houses and fine church structures.

Its wide streets, excellent light and water systems, well-edited

daily newspapers and other advantages, are also the pride of its

people and of the agricultural population of some 15,000 tributary

to it.

There is no suggestion of the untamed, wide-sombreroed, jingling-spurred

West about this peaceful community that almost wrecked a train

and freebooted a thousand tons of coal.

Some time ago the Federal Government took over the original

ditch that began the development of the Yakima Valley, extending

and including it with a larger irrigation system. This, together

with certain private projects now under way, or in contemplation,

means further great increase and prosperity to Yakima with the

extension of its tributary agricultural and horticultural region.

Naturally the Northern Pacific looks with a jealous eye upon

the threatened encroachment of the mysterious North Coast Railway

into this hitherto exclusively Northern Pacific territory. It

has fought, and is fighting with every device and weapon in the

brains and hands of its able counsel, the right-of-way progress

of the North Coast.

But the ungrateful inhabitants view with anything but alarm

the approach of a competing line. "We shall have plenty of

cars, then," they say, "to bring us coal and carry our

products to market."

At the time this article is being written many scores of thousands

of tons of alfalfa are heaped in stacks, and sixty per cent of

the great potato crop is stored in pits, shrinking daily in weight,

while prices are highest, because the farmers cannot get cars.

Hence the popular party cry at the last election was "Hooray

for the North Coast Road!" It boosted O. A. Fechter, banker,

into office as Mayor for the eighth time. Now many Yakima people

believe the Northern Pacific feels vindictive on this score, and

tried to get even on the town by cutting down its fuel supply.

The officials scoff at this as an absurdity, and point to the

very general shortage of coal elsewhere.

But Yakima always has had to depend almost entirely upon the

Northern Pacific for its fuel. The Roslyn mines, some sixty-seven

miles away, are owned by the Northwestern Improvement Company,

a Northern Pacific allied corporation, that in the past has always

supplied an abundance of good coal at reasonable prices to the

Yakima Valley towns, as well as elsewhere through the Pacific

Northwest.

Last Summer the company announced that it had decided to get

out of the commercial coal business; that the entire output of

its mines would be required for its own use in the train service.

"We notified all our leading customers six months ago,"

explained an official to me at the head offices of the Northern

Pacific at Tacoma, "that we should discontinue the trade.

They have had ample notice and could have avoided a shortage had

they taken time by the forelock and purchased a supply from other

sources. You know the old school-book fable of the two squirrels?

The gray squirrel said, 'I will labor and gather and store nuts

while the sun shines and the days are warm,' but the red squirrel

said, 'This is the time to play—I can labor by and by'; but

by and by the winds blew and the snow drifted, and the red squirrel

shivered and hungered and perished. Now these people could have

got coal from the Crows Nest mines north of Spokane, or from Wyoming,

though that's pretty far," he admitted, "or from the

Pacific Coast Company, The mines at Renton, Franklin, New Castle,

Carbon Hill, Cumberland. Burnett or the Occidental. Yes, sir,

the dealers of the Northwest should have laid in a supply in the

Summer."

"But," retort the dealers and consumers, "why

should we unexpectedly be required to order coal months in advance

of our needs? It's the railways' business to furnish cars as we

want them. They have done so in the past—how were we to know

they would be short this Winter?"

Some railway officials have volunteered statements to the effect

that so much agitation against the railways has had a damaging

effect upon the business, and hinted that had the Government and

various state legislatures let them alone, there would have been

less trouble. Many people have pounced upon this as an indication

that something like a vast conspiracy exists for the purpose of

giving the country an "object lesson" of its dependence

upon the good will of the railways. If this be true in the matter

of fuel, the roads have been hoist by their own petard in many

cases, for their reports reveal serious losses because of shortages

of company coal on almost every division.

On all sides

one hears statements to the effect that in the effort to control

the coal supply and gather the profits of the trade unto themselves,

the railways have frozen out private coal enterprises, refused

to build spurs to private mines, or to provide sidings and cars

and otherwise encourage the development of independent mines;

that had the companies stuck exclusively to their proper business

of providing transportation, and had consequently reached out

to encourage new sources of freight, coal would be cheaper and

doubly abundant, for there are vast bodies of untouched coal in

many parts of the Northwest. But the roads retort that they have

had to get control of mines to provide for their own needs. On all sides

one hears statements to the effect that in the effort to control

the coal supply and gather the profits of the trade unto themselves,

the railways have frozen out private coal enterprises, refused

to build spurs to private mines, or to provide sidings and cars

and otherwise encourage the development of independent mines;

that had the companies stuck exclusively to their proper business

of providing transportation, and had consequently reached out

to encourage new sources of freight, coal would be cheaper and

doubly abundant, for there are vast bodies of untouched coal in

many parts of the Northwest. But the roads retort that they have

had to get control of mines to provide for their own needs.

A premature compliance with the new Federal regulation divorcing

the railways from the interstate coal trade may have had something

to do with the trouble. Then, too, bad management is charged.

Instead of equipping themselves to carry more freight, the railways

have been applying profits to paying dividends on heavily watered

stock or have been using their means to buy each other up. "The

money it cost to get Fish out of the Illinois Central would have

hauled a lot of Nebraska wheat to market." The Interstate

Commerce Commission has reported that loaded cars stand "from

two to twenty days at the points, of origin"; cases of "empty

cars lost in congested terminals, or lying unused, sometimes in

solid trains, for equal lengths of time; of engines broken down

from overwork; of trains torn in two by heavy loads; of train

crews working extremely long hours without rest, although making

only ordinary mileage; of cases being common in which loaded trains

took twenty days or more to be moved 250 miles."

Whatever be the causes, the Northwest has encountered an appalling

fuel shortage accompanied by a season of almost unprecedented

cold weather. Yakima was not the first town to confiscate coal

from cars destined elsewhere. Driven to desperate straits two

or three other small points had already startled the railway companies

by seizing coal, in one case an entire car, but it was done in

an organized and orderly fashion, the coal being properly weighed

and duly paid for.

At Yakima the pinch began to be felt as far back as the heavy

floods, which absolutely stopped all train service during the

latter half of November. Thereafter coal arrived intermittently

in small lots, a car or two at a time. Through all the years in

which the company has been selling coal to this large town it

has constructed no bunkers or storage bins here; the consumers

are obliged to back their wagons up to the siding and shovel directly

from the cars. This is a measure of economy, for coal loses weight

from the time it is out of the mine; and the plan has been followed

to keep only enough coal on hand in cars to supply immediate needs.

Consequently any loss of service or shortage of cars is promptly

felt.

Through December, Yakima people and the farmers far and near

had to form in line with wagons day after day, moving up, one

by one, to the car, only to receive at times a maximum allotment

of 500 pounds. This line-up began as early as 3 o'clock A. M.,

and often stretched out many blocks in length. As teamsters charged

from fifty cents to one dollar an hour for this waiting time,

the cost of coal was frequently doubled to the shivering householder.

Complaints and questions assailed the company, and the reply

was usually "car shortage." But reports came to Yakima

of empty coal cars idling at sidings in many places near; and

once, eighteen "empties" stood on a Yakima sidetrack

for several days—quite long enough, said the citizens, to

have run up to the mines, loaded and returned.

So, as conditions grew worse, the people became more skeptical

and indignant. The weather waxed colder and they took to their

kitchens to economize with cookstove heat only. Boxes, old boards

and backyard fences—every scrap that could serve for fuel—went

to drive away the shivers.

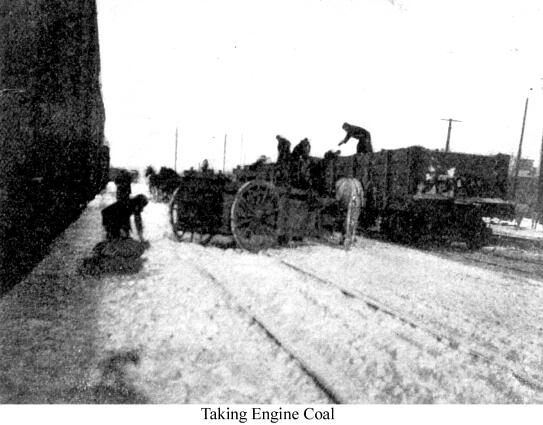

One day several cars of engine coal arrived. This is not of

quite so good quality as the usual commercial grade, and the company

says that its Yakima customers turned up their noses at it. Yakima

denies this and suggests that the company may have had a call

for it elsewhere, and therefore took it away before the town had

a fair chance at it. At any rate, the coal of the raided trains

was of the inferior grade, and the town seems to have made no

complaint about that.

The pinch became more bitter—actual suffering was experienced

by at least 1,500 families. At last, January 6, with the east

wind whistling through the icy streets, a committee of citizens

visited the Mayor at his office in his bank. As a result the following

telegram, signed by Mayor Fechter, Sheriff Grant and Chief of

Police Cayou, was sent to Vice-President Levy at the Northern

Pacific office at Tacoma:

Prompted by desperate conditions,

an organization of more than a hundred people was formed here

today for the purpose of seizing and appropriating the first shipment

of coal, large or small, the company attempts to haul through

North Yakima. Suffering actually exists. Not a pound of coal is

for sale. At least ten cars are needed to relieve the present

conditions, and as much more daily while the cold weather continues.

May we expect relief?

That same day the Yakima Herald had published a very

vigorous article setting forth conditions and mentioning the probability

of summary means being taken by the citizens to secure fuel.

Vice President Levy's reply to the mayor's telegram stated

that a dozen cars were in transit to Yakima, but the dispatch

was not received until late next day. Meanwhile the town had carried

out its threat, seizing twenty-one cars of coal January 7.

Newspaper reports indicated that the affair was sudden, spontaneous,

leaderless. Now, even though driven by dire stress, a modern American

town of churches, banks, culture and commerce, does not suddenly

rise up and take that which belongs to another, without the counsel,

example or leadership of at least one man.

Somehow, from

the fact of the telegram to Mr. Levy, and other features of the

news reports of the affair, I had the notion that the Mayor must

be this unique and determined personage; so Mr. O. A. Feebler,

eight times Mayor of Yakima, was the first citizen whom I visited

to get the story. He did not welcome me; he seemed a trifle embarrassed.

The railway company was not to blame, he said, the people were

not to blame—it was just a spontaneous affair; the people

had to have coal; they were mostly farmers from the surrounding

country, anyway; the railway had done its best—nobody could

be blamed for anything. Suddenly he became suspicious: Somehow, from

the fact of the telegram to Mr. Levy, and other features of the

news reports of the affair, I had the notion that the Mayor must

be this unique and determined personage; so Mr. O. A. Feebler,

eight times Mayor of Yakima, was the first citizen whom I visited

to get the story. He did not welcome me; he seemed a trifle embarrassed.

The railway company was not to blame, he said, the people were

not to blame—it was just a spontaneous affair; the people

had to have coal; they were mostly farmers from the surrounding

country, anyway; the railway had done its best—nobody could

be blamed for anything. Suddenly he became suspicious:

"Don't you put my name in

your article," said he; "I wont have it. I'll sue you

for damages if you mention me."

Clearly this was no leader, at least not the leader I was seeking.

Also, clearly, the Mayor expected and dreaded criticism. Why?

Others informed me. He had failed to meet a crisis for which he

had ample time to prepare. Not that he was expected to stop the

raid, but he made no attempt to regulate it; to provide that the

seized coal should be properly apportioned to all alike, so that

the poorest should have equal chance with those owning or able

to pay for teams and help; also to see that all should pay the

proper price for what they took. Because of this neglect more

than half—perhaps two—thirds of the coal was stolen.

Yakima's business men do not justify this—they regret

it. They feel that the confiscation, while lawless, was excusable;

but they know that the stealing side of it cannot but have an

unfortunate moral effect. They are not proud of the example to

the young of the town.

When appealed to at the beginning, to try to regulate the raid,

the Mayor had said, "I can have nothing to do with it."

Perhaps he felt with the Sheriff and Chief of Police, that by

keeping out of it he could, in a measure, escape responsibility.

So one had to look elsewhere for the man in the affair.

I talked with the railway company's employees at the yards, and

they mentioned I. B. Turnell.

"He set the example—he's a bad one—he raided

coal cars on his own account here two or three times before this

last raid; he's the man that started the crowd to dumping those

coal cars."

So I made inquiry about Mr. Turnell among Yakima people. "He's

all right," they said. "An old railway man; now he's

proprietor of one of our hotels. You can depend upon anything

he tells you."

Almost everybody is ready to abuse the railways privately,

but when it comes to utterance for possible publication, many

business men are curiously shy. "I don't want you to say

I said that," one hears; "you see I have had favors

and may want another sometime—I can't afford to have the

company down on me."

I. B. Turnell was a refreshing exception. A big, tall, two-fisted

American, very square of jaw, very wide between the eyes, and

very wide across the shoulders, he looks you in the face with

a jolly smile, and gives you his views evidently without reservation

because of man, God or the devil. The son of pioneers of Wisconsin—that

state of La Follette and railway legislation—he became a

brakeman in his youth. Having been slightly crippled in an accident,

he studied telegraphy, and thereafter continued in the transportation

service as station agent and telegraph operator. At one time he

managed a railway coal mine in Illinois. Always an enthusiast

in railway matters, he is probably one of those railway men who

have, through luck, lack of opportunity, or perhaps too ready

outspokenness, just missed promotion. Eventually he came to Yakima

as night operator at the Northern Pacific station. His wife opened

a modest boarding-house which prospered so well that the pair

at last resolved to stake their savings and their future in an

hotel enterprise.

They were succeeding beyond their expectations when the coal

shortage began to threaten them with ruin. Having invested their

all, they did not secure a large stock of coal in advance of the

famine, not dreaming of being unable to get what they wanted as

needed. Using from one to one-and-a-half tons a day, when coal

arrived in single carloads and consumers had to wait all day in

line, only to get sometimes not more than 500pound portions, the

Turnells became anxious. To be without coal meant to be without

guests, and without the latter, no means to pay rent or help.

Finally, when but a day's supply remained at his shed, Turnell

visited Freight Agent Meeks, of the railway company, and Agent

Hessey, of the coal company. They could offer him no other consolation

than to say that the Northern Pacific was doing the best it could.

Thereupon Mr. Turnell took a look around the yards and saw a carload

of engine coal resting quietly upon a siding. He hurried over

to the drayage company and said:

"I want a couple of your best teams to haul coal from

a car I have out here."

Before being discovered by Agent Meeks he had secured two full

loads. Seeing Mr. Turnell thus engaged, other teams crowded up:

"That your coal?" asked the drivers.

"Looks like it—doesn't it'?" returned the facetious

hotel man.

"Sell us some?"

"Not a pound."

"How can we get some?"

"By doing as I am doing."

Thereupon, as Turnell's team drove away, the others started

to help themselves; but by this time Agent Meeks had been warned

and he stopped them with resolute language. However, that afternoon

four cars of commercial coal were set off on the siding, and the

town rejoiced.

"I have always found," said Mr. Turnell, "that

when you can't get attention by talking soft, talk hard or do

something to make the other fellow mad, and he'll begin to take

notice."

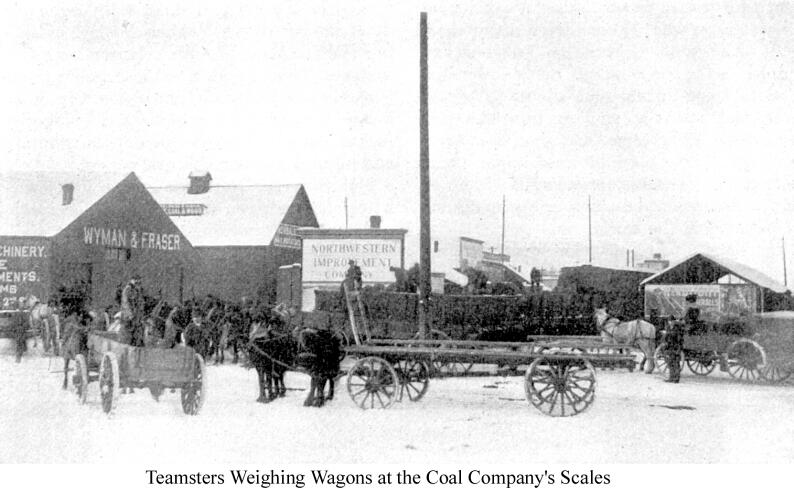

Securing his weight slips from the scales, Turnell went over

to the Northwestern Improvement Company's office and paid the

surprised agent for the coal he had taken.

That happened December 14th. Thereafter, until the holidays,

a fair supply of coal was furnished Yakima; then the company shut

down on the shipments. On January 3d the hotel man again found

himself in desperate straits. Again he found it impossible to

buy coal; again he raided a car of railway coal. He had secured

one big dray load, and was rapidly getting another, while other

teams gathered anxiously around. Suddenly Agent Meeks appeared.

"What are you doing?" he demanded.

"Shoveling coal," replied Turnell, pausing to wipe

his brow.

"You're stealing it; stop or I'll have you in jail."

"Go ahead and get your warrant; I'll go to jail,"

returned Turnell, resuming work.

"Stop," shouted the resolute Meeks, now addressing

the drayman, "or I'll have you prosecuted."

In dismay the drayman dropped his shovel.

"Now put back what you have on your wagon."

The drayman hesitated.

"Drive off," ordered Turnell, "I've got enough,

anyway."

"Don't

you dare to do so," cried Meeks. Again the drayman hesitated.

Thereupon the lawless and square-jawed Mr. Turnell jumped upon

the box and drove the team away to the scales himself. The following

Sunday morning, rising very early, he discovered that the company

was about to set a car of commercial coal upon the siding. Without

waiting for a line to form, or the agent of the coal company to

arrive, he helped himself to six dray loads. "Don't

you dare to do so," cried Meeks. Again the drayman hesitated.

Thereupon the lawless and square-jawed Mr. Turnell jumped upon

the box and drove the team away to the scales himself. The following

Sunday morning, rising very early, he discovered that the company

was about to set a car of commercial coal upon the siding. Without

waiting for a line to form, or the agent of the coal company to

arrive, he helped himself to six dray loads.

"What!" cried Mr. Hessey, when Mr. Turnell tendered

payment, "you got away with six loads when there's hundreds

waiting their turn at it? Do you know what I think of you—you're

a hog—that's what you are."

Mr. Turnell smiled.

"Perhaps you don't care what I think of you," persisted

the indignant agent.

"Young man," retorted Turnell, "be calm—wanted

coal." Afterwards he remarked, "If other people were

willing to be put off and be doled out to until they were ruined

or frozen, I was not. I know there has been no legitimate excuse

for the coal shortage and car shortage everywhere. I believe that

greed and mismanagement from headquarters back in St. Paul and

New York are at the bottom of it. Every subordinate official has

had Jim Hill's motto, 'Maximum load with minimum haulage expense,'

drilled into them until it has become a crime to run a train of

less size than will absorb every ounce of the engine's power.

Consequently there has been nothing but trouble and delay, and

cars take three or four times the number of days to make hauls

that used to be required for the same trips." In which statement

Mr. Turnell repeated in effect what the Interstate Commerce Commission

has reported.

It was on the day following Mr. Turnell's last "raid"

that the committee of citizens visited the Mayor, and the warning

telegram was sent to the Northern Pacific headquarters at Tacoma.

When members of this committee asked the Mayor's advice about

action in case coal should not be forthcoming from the railway

company, he replied, smilingly

"You know that it wouldn't be right for me to advise breaking

the laws."

"But you don't expect us to let our families freeze?"

"No," replied the Mayor, "and under the circumstances,

no jury would convict you for taking the coal if you can get it."

Next day the crowd of drays began to assemble about the railway

yards before daybreak. Noon came and no reply had yet been received

from Vice-President Levy.

All day the

crowd increased. Farmers and orchardists from many miles out of

town foregathered with townspeople, stamping their chilled feet,

rubbing aching ears, swapping stories of hardships suffered at

their homes, or exchanging comments. All day the

crowd increased. Farmers and orchardists from many miles out of

town foregathered with townspeople, stamping their chilled feet,

rubbing aching ears, swapping stories of hardships suffered at

their homes, or exchanging comments.

"That man Turnell's been getting coal," some one

remarked. "We ought to have as much gall as he has."

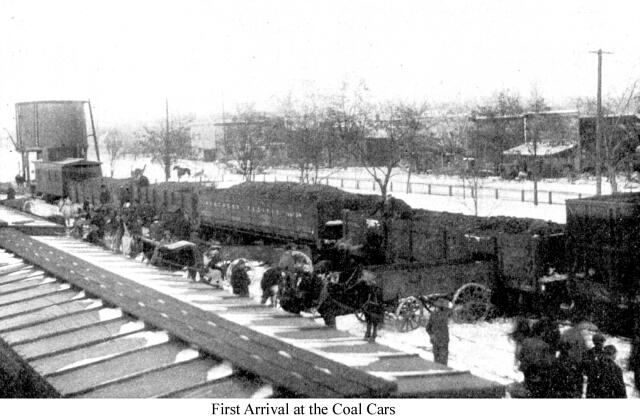

Shortly after 2 o'clock a freight pulled in from the west and

shunted a couple of coal-laden cars upon the coal company's siding.

"Look at that!" cried the crowd, "there's only

a sackful apiece for us."

But the teams peacefully lined up for loads, and Coal-Agent

Hessey had just set about its distribution, when the shout went

out:

"There's a coal train up the track!"

Scores of wagons immediately raced for it, but as the train

proved to be a long one, there was room for all. Every dray, express

and lumber wagon in town was pressed into service, while men and

women ran from one teamster to another to engage the hauling of

small portions of the precious loot.

The engineer and fireman had uncoupled the engine from the

train and run it down to the station while they went to lunch,

so the rapidly increasing crowd was making the coal fly almost

before the railway people were aware. Says the Yakima Herald:

Hundreds of men and boys, women

and a few small girls sailed into the piles that were thrown off

onto the ground and filled boxes, baskets, sacks and even lard

pails and handkerchiefs, but all women who came were helped until

they had all they could carry.

Comparatively a small showing was made in the quantity taken,

however, when the engine backed down, coupled on and started the

train southward. Wagons were quickly driven across the track,

and the crowd gathered begging, pleading, warning and threatening

the engineer, and trying to get him to set the coal cars in on

another siding. He refused, and steamed slowly down the track,

intending to pull out at a rapid gait as soon as the siding was

cleared.

"Dump the cars!" shouted a man. Some say it was Turnell,

but I could not definitely learn who struck off the patent dumping

control of the first car. When the train began to move most of

the crowd scattered, but a considerable number remained on the

cars. These quickly freed the adjustable bottoms of ten of the

cars, and the coal poured down upon the track and along the sides.

The train stalled directly opposite the station. A quartermile

of track was littered deep with coal and the people gathered about

it like flies along a streak of honey.

The engineer managed to get away then with about half his train,

pulling it down the track to another siding. But in a few minutes

another raid had started, and much coal was taken before the harrassed

engineer again got under way and took his train further on still

to Yakima City. The spirit of loot was rampant, and Yakima City

swarmed out like a hive of bees. Here at last the railway people

took charge of the cars, and sold coal to all who came.

Meanwhile another coal train had pulled to the yards shortly

after the first had been stalled at the station. It, too, was

raided with a whoop! and eleven more cars were dumped upon the

track.

The news had spread all over town and the people "come

a-running." Business men and laborers, rich and poor, young

and old, labored with quiet enthusiasm and thorough good nature.

Some people were in a panic lest the hundreds of tons would be

gone before they could get a share. One man was seen to remove

his overalls, tie a cord about each lower extremity, then filling

the improvised sack to the waistband, hurry home joyfully with

the load.

Early in the raid a quick-witted railway employee turned in

a fire alarm, and the Yakima department dashed out across the

tracks. Scarce one of the busy looters looked up from his work,

however, and the ruse was without effect. At last, after dark,

the authorities took charge, and thence on all coal was weighed

and accounted for. That night saw cheer in every Yakima home and

farmhouse round about.

Next day many more cars came in, and, ever since, Yakima is

said to have enjoyed the distinction of having more coal per capita

than any other town away from the mines in the Northwest.

"If you can't get attention by talking soft," says

Mr. Turnell, "talk hard or do something, and they'll take

notice."

Stories Page | Contents Page

|