MY RAILROAD FIGHT IN

AND OUT OF COURT.

Atlantic Monthly—May, 1873

IN the Atlantic

Monthly for December last, I told the story of The Fight of a

Man with a Railroad; and related how, while travelling on the

New York and New Haven Railroad, from New York to New Haven, tendered

in payment for my passage a coupon-ticket marked, "Good from

New Haven to New York," and was dragged from the train because

I refused to pay my fare in any other form, and subjected to severe

bodily injuries. The facts of this case are so familiar to the

public that they need not be recapitulated here. The sequel of

the contest—a suit for damages which, after four trials,

resulted in a verdict of $3,500 in my favor is also well known.

But some interesting and characteristic facts of the legal struggle

still remain to be told; and by way of preface, it should be stated

that my suit against the New York and New Haven Railroad Company

was an action for damages for physical injuries sustained by me

at the hands of its employees; not for its refusal to receive

the ticket which I offered, and which I claimed was a legal and

sufficient tender. I believed, and still believe, that if I pay

for seventy-four miles of transportation on a railroad, I am entitled

to such transportation on presentation of the evidence of my payment

in the form of a ticket, at whichever end of the route I claim

my due. But the basis of my suit was not the denial of my rights

as a traveller. I sued the New York and New Haven Railroad Company,

demanding damages for its wrongful act in beating and maiming

me,—for an assault, in fact. I brought the suit in a Massachusetts

court, first, because the superintendent of the New York and New

Haven Railroad had said that, if I wished to test the case, "he

would give me all the law I wanted, and would show me that the

laws in Connecticut were different from those where I came from";

secondly, because most of the witnesses on my side were residents

of Boston and vicinity, and could attend court in that city without

much inconvenience; and thirdly, because I believed that the Massachusetts

courts represented the highest type of judicial purity. IN the Atlantic

Monthly for December last, I told the story of The Fight of a

Man with a Railroad; and related how, while travelling on the

New York and New Haven Railroad, from New York to New Haven, tendered

in payment for my passage a coupon-ticket marked, "Good from

New Haven to New York," and was dragged from the train because

I refused to pay my fare in any other form, and subjected to severe

bodily injuries. The facts of this case are so familiar to the

public that they need not be recapitulated here. The sequel of

the contest—a suit for damages which, after four trials,

resulted in a verdict of $3,500 in my favor is also well known.

But some interesting and characteristic facts of the legal struggle

still remain to be told; and by way of preface, it should be stated

that my suit against the New York and New Haven Railroad Company

was an action for damages for physical injuries sustained by me

at the hands of its employees; not for its refusal to receive

the ticket which I offered, and which I claimed was a legal and

sufficient tender. I believed, and still believe, that if I pay

for seventy-four miles of transportation on a railroad, I am entitled

to such transportation on presentation of the evidence of my payment

in the form of a ticket, at whichever end of the route I claim

my due. But the basis of my suit was not the denial of my rights

as a traveller. I sued the New York and New Haven Railroad Company,

demanding damages for its wrongful act in beating and maiming

me,—for an assault, in fact. I brought the suit in a Massachusetts

court, first, because the superintendent of the New York and New

Haven Railroad had said that, if I wished to test the case, "he

would give me all the law I wanted, and would show me that the

laws in Connecticut were different from those where I came from";

secondly, because most of the witnesses on my side were residents

of Boston and vicinity, and could attend court in that city without

much inconvenience; and thirdly, because I believed that the Massachusetts

courts represented the highest type of judicial purity.

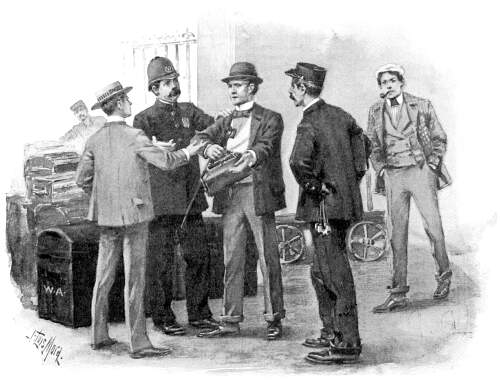

On the day of the first trial, I entered the court-room laboring

under the agitation natural to the novice in legal contests, and

worn with the labors of preparation. When the examination of witnesses

was begun, I was first called to the stand. I was required, as

is the custom, in direct examination, to tell who I was, where

I lived, what my business was; and, these preliminary questions

having been answered, to give a full history of the collision

between myself and the railroad authorities. What was said and

what was done I was permitted to tell, under constant interruptions

from the counsel for the railroad, with, "Your Honor, I object!"

and thanks to these interruptions, and to the slow pen of the

judge, which lagged in note-taking and had to be waited for, I

gave, instead of the concise, straightforward, and symmetrical

account which I intended to give, confused and piecemeal sketches,

which did no justice to my case before the jury. I was wholly

unable to show the animus of my antagonists,—the contemptuous

insolence which characterized their treatment of me in the earliest

stages of the affair, and the reckless brutality which marked

its catastrophe. I was allowed to tell the jury that I was ejected

from the train and received bodily harm: the law recognizes the

fact of an ejection; but it ignores the fact that the victim has

"senses, affections, passions," and that the insult

was put upon him in the presence of a car full of ladies and gentlemen.

The hasty retrospect of my evidence which I involuntarily made

gave me no courage for the next and severer ordeal,—the cross-examination.

The first questions of the counsel for the corporation were gentle,

soothing, and seductive; but, finding that I refused the hidden

pitfalls into which he would fain lead me, he changed his method,

and strove to make me exhibit myself as a "common travelling

agent," who had deliberately plotted to swindle the railroad

company by trumping up a claim for damages for a pretended injury.

He interrogated me as to the particulars of my physical discomforts:

on what days did I suffer pain from my injury? at what hours of

the day? Did the weather affect my state of health? Then he required

me to consider what a mean, contemptible fellow I was, to try

to save two dollars and a quarter by using an old ticket. Then

he demanded, to know why need I be such a "rough," and

get into that disgraceful quarrel, disturbing the other passengers,

assaulting the railroad officials, and making them leave their

business and come all the way to Boston, when I might have paid

my fare, and every thing would have been smooth?

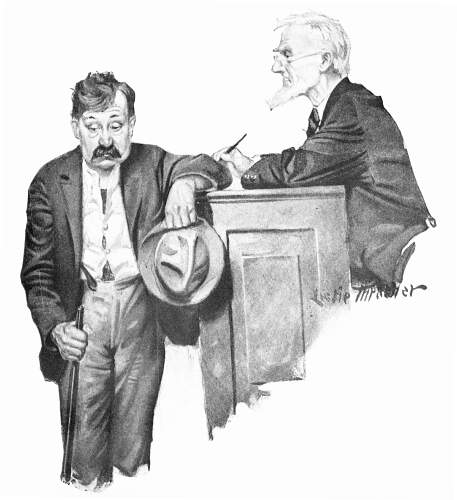

On another

trial the lawyer who conducted the case in behalf of the railroad

company thundered out this command: "Now, sir, look upon

the jury and tell them why you broke the rules of that road,—why

you attempted to use that ticket! A man of your age and your experience

in travelling must have known better. What made you think you

could do it?" A bush followed this indignant outburst. Every

eye in the courtroom was fixed upon me; the spectators straightened

themselves in their seats to listen; the reporters lifted their

heads, and fingered their pencils nervously; the lawyers within

the bar winked at each other significantly; and the presiding

judge bent forward in an attitude of grave expectation. On another

trial the lawyer who conducted the case in behalf of the railroad

company thundered out this command: "Now, sir, look upon

the jury and tell them why you broke the rules of that road,—why

you attempted to use that ticket! A man of your age and your experience

in travelling must have known better. What made you think you

could do it?" A bush followed this indignant outburst. Every

eye in the courtroom was fixed upon me; the spectators straightened

themselves in their seats to listen; the reporters lifted their

heads, and fingered their pencils nervously; the lawyers within

the bar winked at each other significantly; and the presiding

judge bent forward in an attitude of grave expectation.

My answer was deliberate, for I had outgrown my original nervousness,

and was hardened to the asperities of judicial inquisition: "On

general principles, when I pay a dollar for a thing, I am entitled

to the equivalent of that dollar, whether I buy a railroad ticket

or potatoes."

"Ye-e-s," rejoined the lawyer, slowly, and with a

sneer in every word, "and when you buy potatoes,

you think you can take it out in sugar or tea, if

you prefer." He had made a good point, he thought, and he

cast about the room a look inviting congratulation.

"No," I said; "I do not think I can take it

out in sugar or tea. But I think, if I buy a barrel of potatoes,

it's nobody's business but my own whether I take the head out

of the barrel and eat through that way, or tip it

the other end up, and go through that way!"

For once I had the whole court with me in a laugh, in which

judge, jury, lawyers, and spectators took eager part; and my inquisitor

dashed his papers on the table, and dropped into his seat.

During the last trial I had testified that I knew tickets had

been used "backwards" on the road, and I believed such

usage amounted to a custom. My tormentor asked why I did not bring

witnesses to prove such a custom. I replied, that we did introduce

a witness for that purpose, but the defendant's counsel refused

to permit him to testify, declaring that the custom of the road

had nothing to do with the case; only the rule of the road

was to be considered. The counsel denied this, and affirmed that

be would not have objected to such testimony, if we had been able

to produce it. A gentleman sitting among the spectators rose and

whispered to my lawyer; and as soon as I left the witness-stand,

he was called and sworn, the opposing counsel watching the proceeding

with undisguised curiosity. "Mr. Witness," asked my

lawyer, "you have travelled a good deal on the New York and

New Haven Railroad, have you not?" "Yes, sir."

"State whether or not you ever had any tickets to go in the

reverse direction, and how they were marked."

Before the witness could answer, the counsel for the railroad

sprang up and vehemently protested against the introduction of

the evidence. The judge evidently did not comprehend the situation,

and turned an inquiring look upon my lawyer, who answered it by

saying, "Your Honor, the defendants have asked me why we

did not call witnesses to prove the custom of using tickets 'backward,'

and said that they should not object if we did so. Now we have

put this gentleman on the stand to show that he had such tickets—"

"Yes, and used them too," interrupted the witness. "Stop,

sir!" cried the judge, "you are not to testify until

you are told to do so." But the caution was too late; the

mischief was done; and again all present, appreciating the humor

of this breach of legal etiquette, united in a hearty laugh. It

was plainly unnecessary to pursue the examination of this witness

further, and he was permitted to stand aside.

The other witnesses for the plaintiff, ladies and gentlemen

who were in the car at the time of my ejection, gave their evidence

on each trial, clearly and impressively, corroborating my own

in all material points, and resisting successfully the diligent

efforts of the opposing counsel to lead them into self-contradiction

and confusion. They, too, were badgered and brow-beaten, as I

had been; and their plight in the grasp of the cross-examining

lawyer, though not edifying, was instructive in so far as it proved

that the law is no respecter of persons. All the evidence 'for

the plaintiff having been put in, the defendants' counsel opened

their case in a brief speech, in which he quietly assumed, and

seemed to take the jury into partnership in the assumption, that

I had deliberately laid a plan to cheat the railroad company,

and coolly stigmatized my suit for redress as a "fraud."

He then introduced his witnesses,—"the honest, hard-working

men who had been styled 'roughs' by the other side," and

whose advent was now witnessed by the spectators with ill-concealed

amusement. The contrast, in fact, between the witnesses for the

two sides of the case was too glaring to be ignored,

The first honest witness was as prompt as a well-drilled recruit.

He described the incidents of my ejection: the conductor called

upon him and some of the other "boys" to take a man

out of the car; they attempted to carry out his order quietly,

but the man refused to go; therefore they laid gentle bands on

him, whereupon the man kicked and struck and bit, and he (the

witness) had to take hold of the man's hands to restrain his violence.

He swore positively that it took six men to move the man. In answer

to an inviting question, he eagerly testified that he saw Mr.

Coleman bite one of the boys on the arm,—right through the

woollen garment that the man wore. The story was clear, concise,

and told with an air of confidence that was quite impressive.

"Mr. Witness," said my lawyer, beginning the cross-examination,

"you said just now that you saw Mr. Coleman bite one of the

men?" "Yes, sir; on the arm. "Which arm?"

The witness hesitated; he was well prepared in generalities, but

not in details. Presently be answered, "The left arm."

"How many men had hold of Mr. Coleman at this time? "

One man was on his left side and another on his right, others

had him by his legs, and I was in front." "These men

were abreast of Mr. Coleman, taking him out squarely through

the car, were they?" "Yes sir." "Will you

swear to that positively?" "Yes, sir," said

the witness, resolutely. "Careful, now; are you sure of

that?" Yes, sir; I am sure of it." "On

which side of Mr. Coleman was the man who was bitten?" Again

the witness hesitated, and his face, hitherto calm, grew flushed

and anxious. But he answered at last, "The left side, sir."

"Will you swear positively to that also?" "Yes,

sir; I swear positively to it." "Now, sir,"

resumed the lawyer, "do you not know that a man of Mr.

Coleman's breadth in that narrow car aisle would completely fill

it, so that neither two men nor one could stand at his side, as

you swear they did?" Flustered, but not daunted, the witness

explained, "The men were a little back of Mr. Coleman";

and witness quitted the stand, leaving the court to meditate on

the strange spectacle of a man curving his giraffe-like neck,

and fastening his teeth in the left arm of a man who stood

on his left side, and a "little back of him!"

Several other honest witnesses gave similar testimony as to

the biting, and as to the violent behavior of the plaintiff, and

the gentle but firm deportment of the railroadmen; these latter

struck no blows, but several were delivered by the plaintiff.

The harmony of the witnesses was beautiful. They seemed to have

beheld the scenes which they described with a single eye: as to

the biting, the arm bitten, and the position of the biter, their

agreement was perfect. At this stage of the proceedings a recess

was taken. On the reassembling of the court, other witnesses for

the railroad were examined; but, strange to say, not one of them

could give any particular information as to the biting; they swore

that Mr. Coleman did bite, but, though they had enjoyed the same

opportunities for observation with their predecessors on the stand,

they "couldn't exactly remember the details." Such is

the effect of lunch.

The conductor told a plausible story, modelled carefully on

my own statement, but differing in certain points that could be

turned against me. It will be remembered that he told me in the

cars that the directors had made a "rule," forbidding

him to take tickets backward. On cross-examination, my counsel

asked him where he was accustomed to turn in his tickets to the

company. He attempted to evade the question again and again, but

finally answered, with painful reluctance, "in New York."

It was further extorted from him that the tickets were turned

in at New York whether taken in going to or from that city; that

it made no difference which way my coupon was used; and,

finally, that, the directors of the road had never given him (as

he asserted to me) a rule against taking coupons "backwards,"

but that the superintendent had verbally ordered him not to take

them, about three years before! This superintendent, who, with

his son, wrenched me from the train at Stamford when I attempted

to re-enter it after my ejection, was obliged to swear that it

was the exclusive right of the directors to make "rules,"

and, further, that they never had made a "rule" touching

the ticket question; he himself having verbally instructed the

conductors not to take tickets "backward," which be

had no shadow of authority to do. Thus it seems that the "rule"

for the violation of which I had been mildly rebuked by the servants

of the railroad,—a violation which was the soul of the defence,

its single excuse and answer to my allegations—was not

a " rule" at all, but a mere verbal order given

by an unauthorized person. Yet, in the face of the declaration,

by one of the highest officers of the road, that there was no

"rule," the judge charged the jury that a "rule"

had been broken, that I was a trespasser, and that the railroad

company had a right to eject me from the train, employing the

necessary force and no more! Such a charge concerns every person

in the community; for it seems that any of us, for disobedience

to a non-existent rule, may be brutally dragged from a railway-car,

and, seeking redress, shall be informed by the court that the

railway company is responsible only for "excess of violence."

The examination of the superintendent having been concluded,

the counsel for the railroad stated to the court that the victim

of Mr. Coleman's carnivorous ferocity had been discharged from

the road immediately after his misfortune; that diligent search

had been made for him, but in vain. By one of those dramatic felicities,

so frequent in fiction and so rare in real life, just at this

juncture a telegram was brought in announcing that the bitten

man had been found, and would arrive on a train due in ten minutes.

The judge granted the delay asked for, and the spectators brightened

up in anticipation of new and measurably tragic revelations. The

delay was brief. In a few minutes the door of the courtroom was

thrust open, and in rushed the witness, breathless with haste.

A brisk, bronzed person he was, self-contained and self-satisfied,

with locomotive gait, and a habit of gesture suggestive of brake-rods.

He mounted the witness-stand, was sworn, and delivered his direct

testimony with easy indifference, coupling his sentences as he

would couple cars, with a jerk. This is his story in brief: "The

conductor c'm out the car 'n' said,'' S man in there want ye t'take

out.' Went in the car, and he said, 'That's th' man: put 'im out!'

I jes' took 'im up and carried him out through the car out on

t' th' platform th' depot, an' took 'n' set 'im down, an' never

hurt him a mite." "Did Mr. Coleman bite you?" inquired

the counsel for the railroad. "Yes, sir." "Did

he bite you on the arm?" "Yes, sir." The lawyer

asked him no more questions, evidently satisfied with the effect

of his evidence thus far, and possibly remembering that, unlike

the other witnesses for the road, he had not enjoyed the benefit

of lunch. Remitted to my counsel for cross-examination, the witness,

well pleased with his success, and confident in his own powers,

met the inquisitorial onset with calm dignity.

"Mr. Witness," said the lawyer, "you were in

the car on the day when Mr. Coleman was taken out, were you? Yes,

sir; I took him out myself." Ah! you assisted the men to

take him out, did you?" "No, sir; didn't have no men;

took him out myself." "O, you took him out alone, then?"

"Yes, sir; took him out alone." "You swear to that?"

"Yes, sir; swear to it." "Nobody helped you?"

"No, sir; took him out myself" Well, sir," pursued

the lawyer, "you must be a stout fellow, to handle a man

like that. Won't you please describe just how you took him out."

"Well, I jes' went up to th' man, reached one arm 'round

his neck, so fashion, had his head right up here on my arm, 'n'

I jes' took 'im right through the car out on t' the platform th'

depot, an' set 'im down and never hurt 'im a mite."

Every face was intent upon the witness and not a sound was

heard save his voice, though there were premonitory symptoms of

laughter. With a suavity delightful to see, the lawyer said, while

he scanned the compact frame of the witness, "Why, you must

be a powerful fellow!" "Yes, sir.; I'm big enough for

him." "Well, now, will you be kind enough to tell the

jury, did Mr. Coleman strike anybody?" "No, sir; I didn't

give 'im no chance; I had 'im." "You swear to that positively?"

"Yes, sir." A look of dismay and disgust settled upon

the faces of the earlier witnesses for the road, who had graphically

and minutely described my violent resistance, my kicks and blows.

The spectators giggled, and even the judge relaxed the solemnity

of his visage. "Did anybody strike Mr. Coleman?" continued

the lawyer. "No, sir; I had 'im and didn't give 'em no chance."

"You swear to that, too? " "Yes, sir." "Well,

Mr. Witness, when you had Mr. Coleman's head upon your arm, as

you described, I suppose you had his face turned a little toward

your breast?" The witness, eagerly following this description

of the situation and the gestures which illustrated it, his face

now flushed and beaded with perspiration (for the work was harder

than he had thought it), nodded assent. "Mr. Coleman's mouth,

then, would come about there?" inquired the lawyer, pointing

to the inside of the arm, next to the body. "Yes, sir; that's

just the place where he bit me." "You swear to that

positively?" "Yes, sir, positively." All the witnesses

for the road, except the conductor, who did not commit himself

as to the biting, swore emphatically that the bite was on the

outside of the left arm, some of them placing the bitten man upon,

the left of the biter; and now comes a third untutored witness,

who claimed to be the sufferer and who of course ought to know

the place of the bite, testifying with equal positiveness that

the bite was on the inside of his arm. Even the counsel for the

road could not refuse to join in the universal merriment which

ensued.

On subsequent trials all this testimony as to the biting was

rearranged. The victim of my ferocity was obliged to share the

honor of taking me out with five auxiliaries, and the bite was

transferred to his right arm. Being a draughtsman, I had measured

the car, and was ready with a drawing to show that the new theories

of the defence as to the method of taking me out left just three

inches for the movement of each stalwart brakeman as he walked

at my side.

I Suppose that I need give no extended report of the argument

of the road's counsel. He took the highest ground,—the ground

that the public had no right to question the management of the

road; that the company owned it, and had the right to manage it

as any other property is managed by a private corporation: that

is, he denied the fact that the public is virtually a partner

in railroad companies, which it creates and lifts into power

by grants of franchises and land. Indeed, this distinction between

public and private corporations has been carefully ignored by

the judiciary of the country; and to this the present alarming

domination of railroad corporations is mainly traceable.

I may say, for the encouragement of those who look to the courts

for deliverance from a railroad tyranny, whose bonds the judiciary

seems willing enough to rivet, that, in every trial, my counsel

carried the jury with him, one single juror of the forty-eight

excepted. This juror was said to have been formerly an employee

of the New York and New Haven Railroad. The action of the several

juries, so far as the public is concerned in it, is satisfactory

and cheering; for it indicates unmistakably that the spring of

railroad power in our courts is not in the deliberate judgment

of intelligent men; but the judges' charges were in effect restatements

of the arguments of the counsel for the railroad touching the

general question of the rights and powers of railroads. The juries

were instructed that the public has no voice in the affairs of

railroads; that contracts with passengers were to be made on conditions

fixed by one party, the railroad; that if a passenger violated

its regulations, an assault upon him by the agents of the corporation

was justifiable, though these latter must be careful to avoid

excess of violence. The juries were also instructed that if they

found that, in this case, the defendants had employed an excess

of violence, they must not allow punitive damages, but only such

as would compensate the plaintiff for his injuries. Despite these

instructions the four juries promptly brought in verdicts in my

favor, each one giving heavier damages than its immediate predecessor.

On the second trial the jury disagreed, owing to one of its members;

I am informed that many of his associates desired to award me

$15,000. The first jury agreed upon a verdict of $10,000; but

one of their number, versed in the ways of courts, suggested that

it would probably be set aside, and that I would consequently

be subjected to great trouble and expense; so they reduced the

figures to $3,300, which was increased to $3,500 on the last trial.

Such, briefly sketched, were some of the features of my railroad

fight in court. The reader will recollect that I—a man not

rich and ill able to afford the time or expense of such a contest

with an opulent corporation—was compelled to repeat this

fight three times: first, because the verdict of $3,300 awarded

excessive damages for one of the most brutal assaults ever committed,

and the infliction of lifelong injuries; and subsequently upon

pretexts even more trivial. The judges ruled that the roads had

all the rights in the case, and I had none. They ruled that an

order given by an unauthorized person, and confessedly no regulation,

was a regulation, and that, if I violated it, I must take

the consequences. They declared in effect that a railroad ticket

was a contract, though it bore no government stamp, and was made

by a single party. They suffered the wild and contradictory swearing

of the road's witnesses to go unnoticed. But in spite of the judges,

and their rulings, the juries were for me.

My fight out of court has been a different matter. The publication

of my first article has called forth comments from the press in

every part of the country. I have seen more than one hundred notices

and articles based upon it, all of which, with three or four exceptions,

applaud my course, and express the public sympathy with me in

terms which I could not reproduce without seeming to turn to my

own honor a matter which I am anxious to regard in an impersonal

light. These articles have appeared in the most important journals

of the country; I believe that no journal of influence has left

the case unnoticed; and the country press has treated it as generously

and courageously as the great newspapers of the city, which are

supposed to be less susceptible to local influences, and more

independent to advertisements and free passes. Nothing could be

more instructive and interesting than this almost universal expression

of public opinion by the public press in regard to the arbitrary

and despotic management of our railroads. Many of the journals

recur to the subject again and again, and all testify to the fact

that every railroad passenger has seen or felt some outrage or

oppression against which he has longed to protest.

This fact is even more vividly enforced by the private letters

which have not, ceased to come to me since the publication of

my paper. They are from women as well as men, and from persons

in every station of life and every department of business, in

nearly every State of the Union; and they congratulate me, not

only upon my personal victory, but also upon my demonstration

of the fact that it is possible for an individual to stand up

in defence of his rights against a railroad corporation. They

recite the tyrannies and meannesses of different railroads, and

catalogue the stratagems by which railroad managers bind the hands

that should protect the people from their encroachments. If it

were possible to print these letters together, they would constitute

an indictment whose force would impress even the most easy-going

and spiritless citizen. I make an extract from one of them which,

brief as it is, carries a tremendous significance. The letter

was written by a resident of another State, who, like myself,

had dared to sue a railroad.

He writes:

"But I am not yet out of the woods, as

the case is again before the lower court, where it is delayed

from the fact that most of our judges are disqualified from trying

the case; one is secretary of the company; others are stockholders;

others, before their elevation to the bench, were regular counsel

for the company."

What is true in that State is true in all; the trail of the

railroad is over every judicial bench in the country. In one of

the great States of the West, a correspondent writes that one

of the judges of the Supreme Court permits a railroad corporation,

which is party to several suits pending before him, to transport

free of charge building material for his new house, thereby saving

him from five hundred to one thousand dollars in freight money.

In New York some judges had become openly vendible; in other States

they are more coy and circumspect; but in no State are they above

suspicion, as judges ought to be. It is a notorious fact that

railroad corporations regard the free-ticket system as one of

the strongest bonds wherewith they have bound the American people.

On the press, on the legislature, and on the judiciary they bestow

"passes" with lavish hand, well knowing that every man

who accepts one virtually assumes an obligation to favor the corporation

which gives it. They do not count upon an immediate return, but

are content to bide their time. Some day their road may need defence

in the newspapers; or it may need an extension of its privileges

at the hands of the legislature; or it may be a party in an important

lawsuit. For all these contingencies it is prudent to provide.

One of the most curious and interesting of the letters I have

received is from a former railroad man, in the West, who gives

me his full name and address, and says,

"I wish to express my thanks to you for

having benefited the country by your victory over a railroad,

and by the article just sent forth; the statements of which I

can testify are true, having been a railroad agent in a Western

State."

From Albany a prominent merchant writes to congratulate me,

and to express his own feeling in regard to the "arrogance,

tyranny, and oftentimes brutality exhibited by railroad officials

and employees"; and from Washington a gentleman, distinguished

in literature and society, sends me his thanks. "I have for

years," he adds, "called the attention of the public

to the extortions and illegalities of our railroads. But it is

slow work, because, as you have very well shown, the companies

bribe indirectly, by propitiation, men who are, some of

them at least, too honest to be bribed directly ..... But let

us hope, some day or other, those fellows may hustle or maim a

senator by mistake"; or, let me suggest, as even more to

the purpose, a judge of the courts.

A letter from a well-known firm in Boston asserts that our

merchants are doing business under a worse despotism than exists

under any arbitrary government of the Old World. I need hardly

say that my correspondents abound on the line of the New York

and New Haven Road, and that they one and all hail my success

with joy, and reiterate those well-known complaints of the road.

I may be excused, I trust, for copying finally a letter from

a lawyer of Cambridge, Massachusetts, which is remarkable for

the practical turn of the writer's sympathy:

"Accept my sincere thanks for your

article in the December Atlantic. I have been intending to write

you a letter of thanks for two weeks past, but am now specially

moved to do so, as I can add to my own the high commendation of

my friend Mr. ——, our United States minister to ——,

who spent last night at my house. If you will accept it, I will

send you fifty dollars as an earnest of my thanks, and as my contribution

to your good work."

Naturally, I could not accept my correspondents offer, but

I valued it as a movement in the right direction. The impulse

which prompted it has already taken a practical shape in the West,

where, as I learn, the farmers and merchants have already begun

to form unions for their common defence against the railroads.

The members contribute to a fund which is to be used in attacking

the illegalities of the roads in the courts, and for defraying,

at the common cost, the expenses of suits which private persons

would not dare to undertake. This is a thoroughly practical movement,

and altogether preferable to the secret political organization

against the roads which has also been set on foot. Such a party

is predestined to be the prey of politicians, who will betray

it on the first occasion; but a co-operative society seeking justice

in the courts must succeed, even though the judges who make railroad-law

preside, with free passes in their pockets. There, with jurors

who have never been connected with railroads, —jurors chosen

only half as carefully in this view as jurors in murder cases

are chosen,—the victim of railroad tyranny is sure of justice

at last. No compromises should ever be accepted. A thousand suits

at law would do more to right the public than any amount of legislation.

The most encouraging and satisfactory characteristic of my

railroad fight out of court is that it is still going on, and

I trust that it will continue till the insolence of these railroad

corporations is curbed, and they are taught their single and true

function of common carriers for the sovereign people. They are

servants who have usurped the mastery. It is time they relinquished

it.

John A. Coleman.

Stories Page | Contents

Page

|