|

||||||

| ||||||

|

Harpers Monthly, July 1854

THE Catskills follow a grand course from north to south in the eastern part of the State of New York. Their position is at an aggregate remove of ten miles west of the Hudson. The interval of undulating and fertile country is thickly studded with cities and villages and highly cultivated farms. Geologically speaking, the Catskills occupy the counties of Sullivan, Ulster, Greene, Schoharie, and Albany; but pictorially considered, they are in the county of Greene alone; within whose limits are found all the loftiest peaks, and all the chief resorts of the tourist and the artist. The village of Catskill, upon the Catskill Creek, near its confluence with the Hudson, is one hundred and eleven miles above New York; and is accessible from that city almost hourly by steamboat or railway. Good coaches are always waiting to convey travelers thence, over a glorious route of twelve-miles of enchanting valley and hill country, to the regal halls of that famous cloud-capped palace—the Mountain House. This noble edifice, lifting its grand facade above a rocky cliff twenty-five hundred feet in air, forms a curious and beautiful feature of the mountain landscape, in the passage of the river, from all the distant towns and elevations to the eastward; and as it comes again and again into view in the gradual approach from Catskill; and finally, as it rises proudly above our heads, while slowly ascending the precipices which it so grandly caps.

"To the philosopher what is it not?……The fields and waters seem to him to-day no more truly property than the skies which shine down upon them; and to think how some below are busying their thoughts about how they shall hedge in another field, or multiply their flocks in yonder meadows, gives him a taste of the same pity which Jesus felt in his solitude, when his followers were contending about which should be greatest.''

There are here extraordinary facilities for enjoying this high delight of nature. The orient is before you, unobstructed by intervening hill or object whatsoever. The first smiles of the monarch of the morn are yours, dimmed by the intervention of a few jealous or, perhaps, welcoming clouds, for they laugh and dance with radiant beauty and grace as his burning caress calls the roses to their checks. The dense sea of vapor which overhangs the wide valley far below, is broken as by the wand of an enchanter, and it rises into the upper air, like the smoke of a thousand watch-fires, bringing I hill, and vale, and stream, with all their myriad details into active and joyous life and motion. It is a curious and oftentimes an amusing study, to observe the varying degrees of emotion or indifference with which more poetic or obtuser natures witness this sublime spectacle: the highly spiritual temperament worshiping with religious oneness and fervor; the intelligent and philosophic mind satisfied with its grand beauties; the simply wondering observer gazing with new and pleased astonishment; down through all the shades of coolness and insensibility—lazily scanning the scene from chamber window, or enduring terrible martyrdom, standing in the shivering chilliness of the early morning air.

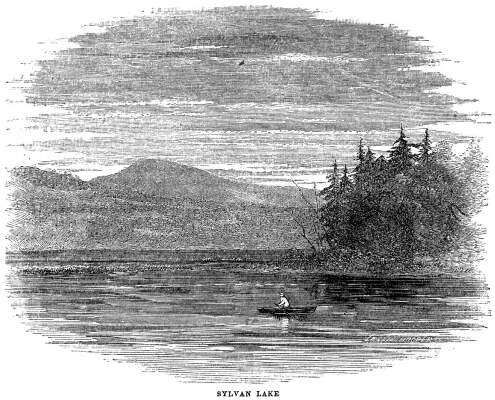

The next pilgrimage which the tourist is expected to make is to the two charming lakelets, which, in their strange mountain bed, add so greatly to the interest of 'he surrounding points. Their waters supply the renowned Catskill Falls, which we shall reach in due order. An easy wagon passes the lakes at intervals throughout the day, on its way from the hotel to the cascades, but an orthodox Syntax will indignantly scorn this vulgar mode of locomotion, and bless the man who first invented boots. A few minutes' walk will bring you to the margin of the Upper or Sylvan Lake, a view of which we add to the list of our pictorial memories. You may pass an hour or two delightfully in strolling upon the pleasant shores, or you may enter one of the skiffs which skim the waters, and mingle your voice in happy carol with the murmur of the breeze, which never fails to play with the bright image cast by tree and rock and sail on the pellucid bosom of the lake. When these more demonstrative expressions of pleasure, which the scene will always draw from the coldest hearts, are spent, you may give your thoughts to the poetic page, or to the dreams of the romancer, occasionally glancing at the fly which you have cast upon the water to lure the wary trout. In short, unless you can find here some or other source of pleasure, God pity you, unhappy man!

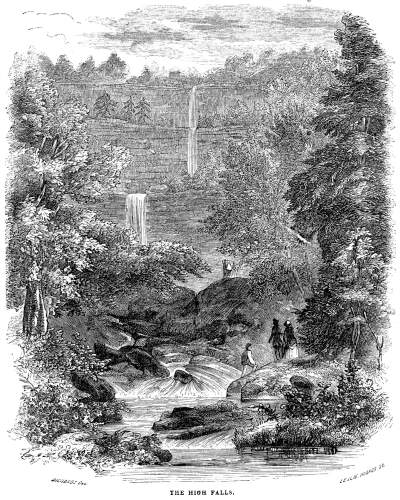

Now for the Falls. Approaching from the Mountain House, you of course see them first from above. Before you commence the descent of the long flights of wooden steps which lead to the base of the cataracts, you enter a very pleasant sort of cafe, where you may strengthen your physical man with any species of refreshment, from brandy-punch (in the quality of which you may place the extremest confidence of true love) to a cooling ice-cream or a draught of sparkling lemonade. At the same time you may relieve yourself still farther by lightening your purse to the extent of a quarter, which the placards posted around will instruct you it is expected that gentlemen will pay to keep the stairs, the Falls, and the guides, in order. This assessment also rewards the Neptune of the spot—our venerated friend Peter Schutt, whom you must cultivate—for "letting off the water!" For, be it known unto you, that a dam is built above these Falls; by which ingenious means the stream, restrained from wasting its sweetness on the desert air, is peddled out, wholesale and retail, at the tale of two and a half dimes a splash! Cooper says, in the "Pioneer," touching these cascades: "The stream is, may be, such an one as would turn a mill, if so useless a thing was wanted in the wilderness; but the hand that made that 'leap' never made a mill!" Alas! since Cooper's hero lived, the "wilderness" has "blossomed as the rose," and the once free torrent is now chained by the cold shackles of the spirit of gain. Happily, after being thus bound, it laughs with the greater glee when released; and one will forget while he gazes, spell-bound, upon the world of spray, that, like the sunshine in his own heart, it will not always last. To continue our loan from the graphic picture in the Pioneer: "The water comes croaking and winding among the rocks, first so slow that a trout might swim in it, and then starting and running, like any creature that wanted to make a fair spring, till it gets to where the mountain divides like the cleft foot of a deer, leaving a deep hollow for the brook to tumble into. The first pitch is nigh two hundred feet; and the water looks like flakes of snow before it touches the bottom, and then gathers itself together again for a new start: and, may be, flutters over fifty feet of flat rock, before it falls for another hundred feet, when it jumps from shelf to shelf, first running this way and that way. striving to get out of the hollow, till it finally gets to the plain." When you reach

the base of the first Fall, your guide will perhaps conduct you

over a narrow ledge behind the falling torrent, as at "Termination

Rock" at Niagara. Then reaching the green sward on the opposite

side of the stream, you may make a signal to Peter Schutt, who

will be looking over the piazza of his cafe above, and if you

have duly settled between you the telegraphic alphabet, in such

case made and provided, he will attach a basket to the projecting

pole, and incontinently there will descend sundry bottles of the

very coolest Champagne of which the vineyards of France ever dreamed.

You may then repose yourself half an hour or more upon the mossy

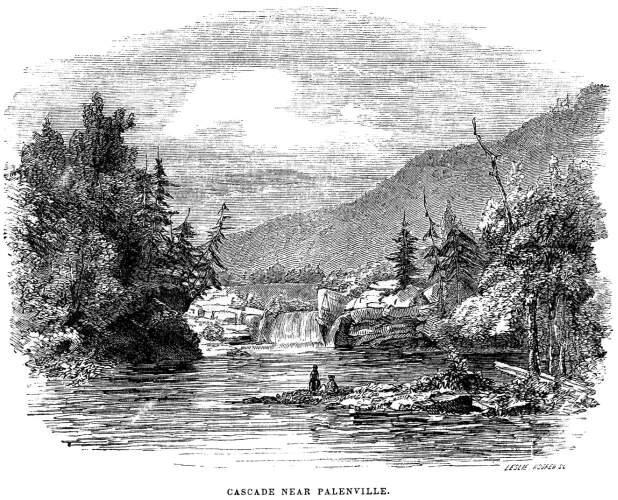

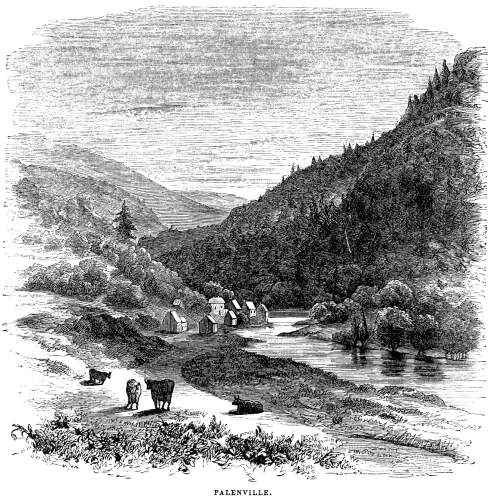

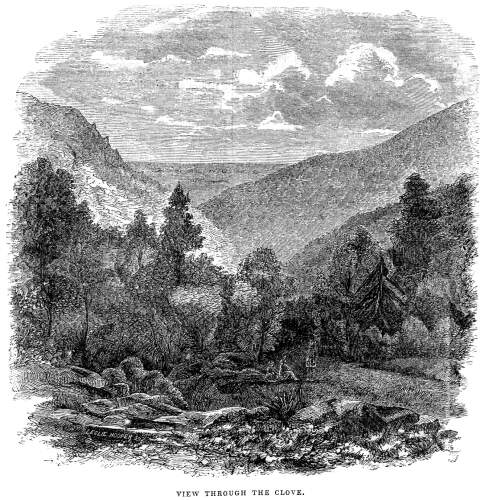

couch aforesaid, imbibe Neptune's nectar, The passage of the gorge we now traverse is replete with interest. Up and down we go for a varied mile, urging our way through the deep tangled wild wood, leaping from rock to rock across the brawling stream, contesting the track with prostrate trees, gazing reverently upward upon sullen cliffs, or far below into the deep chasms where the plunging waters lie inert for a moment after their unwonted toil. At the close of this brief but brilliant episode in our tour, we open upon the fine turnpike road which crosses the mountains through the clove of the Kauterskill. We shall perhaps explore this picturesque gorge more intelligently if we commence the jaunt at the mouth of the passage, where one or other of the little inns of Palenville will afford us a very tolerable if not luxurious bivouac. Very few of the thousands who annually visit the Mountain House

ever explore this, the most charming part of the Catskills. The

village of Palenville, apart from its location, is a hamlet of

the most shabby sort. It barely supports one ill-furnished store,

two primitive way-side taverns, a Methodist chapel, a school,

a post-office, and a small woolen factory. With the exception

of such gentry as the blacksmith, the wagon-maker, the cobbler,

and the tailor, the inhabitants employ themselves in the factory,

in neighboring sawmills, tanneries, and in the transportation

of lumber and leather to the river landings. In the vicinity are

a few of the better class of homesteads and small farms. The situation

of Palenville, at the portals of the hills, gives you an equal

and ready access to the great valley on one side, and to the mountain

solitudes on the other. Eastward from the hamlet, half a mile

is a most lovable cascade, too much neglected by the few travelers

who come to the clove. A minute's walk through a dense copse will

bring you to an unexceptionable point of observation. Seated upon

a moss grown rock, and shaded by the "sloping eaves"

of giant hemlocks, you "muse on flood and fell." At

your feet lies the deep basin of dark waters, the clustering foliage

toying with their busy bubbles. The cascade and its accompanying

rock-ledges fills the middle ground, exposing beyond the entire

stretch of the southern line of hill, until it is lost in the

golden haze of the setting sun. At this evening hour, too, the

sunlight kisses only the tops of the trees and shrubs, and glimmers

upon the upper edge alone of the falling water. A little way below

and this picture occurs again, in a scarcely less pleasing form.

Still further eastward are other smaller yet exceedingly agreeable

glimpses of cascade and copse. The greater beauties, however,

lie west of the village, and along the bed of the torrent, rather

than on the frequented path. You must make a thousand detours

to properly explore the varying course of the brook which dashes

and leaps through this magnificent pass. You must risk your neck

now and then in descending to the arcana of a ghostly glen far

below the roadside, and anon you must struggle manfully to pull

your aching limbs back again. Beyond this point the highway offers very little of interest, excepting in the general vistas of the ravine, up and down, as you ascend the ridge. The waters may, however, still be followed two or three hundred yards, to the base of another fall, not less noticeable, though of totally opposite character to that which you have just left. This is known to all habitues of the clove as the Dog-Hole. It is a perpendicular leap of some sixty feet. The stream here, extremely narrowed by the rocky banks, rushes over an immense concave ledge, into a caldron from which a fish could scarcely emerge. We were once passing the day here sketching; undisturbed, save by the music of the waters, and the melody of birds; when, as we finished our drawing and were examining it with inward satisfaction, we were suddenly startled by a near and unusual noise. Remembering that the much dreaded snake moves more silently, we ascribed the fracas to the passage of stray cattle, or to the noisy amours of the winds, and resumed our meditations. Again were we startled, and this time, with a consciousness of some extraordinary presence; when looking up, we caught the wondering eye of a remarkable old denizen of Palenville, and heard him ejaculate, as he stared at our picture, "'Tis most onaccountable!" This is a favorite expression of the good old man's. "Is that you, Uncle Joe!" we exclaimed, much relieved, "we took you for a bear!" "O no!" said he, "there ain't many bears in these parts now, and they never disturb a body. When they hear a man coming, they always bear away! he, he, he! 'Tis most onaccountable!" Uncle Joe

looks out and observes the clouds gathering or rolling away, and

each circumstance strikes him as most unaccountable; in the long

winter evenings he loses, at dominoes in the sitting-room of the

village inn, and in his peculiar nasal utterance still thinks

it "most onaccountable!" At the Dog-Hole you must again betake yourself to the road, and you will do well to keep therein, until you reach the sprawling shanties of a deserted tannery in the "Upper Clove." These tanneries are numerous in the Catskills; and the business affords employment and bread to very many people. The great abundance of the hemlock, which supplies the necessary bark, gives extraordinary facilities for the labor. In Prattsville, some thirty miles west of the Clove, Colonel Zadoc Pratt has established one of the most extensive tanneries in the land. This feature of the country is not at all calculated to win the love of the hunter of the picturesque. It destroys the beauty of many a fair landscape—discolors the once pare waters—and, what is worse than all, drives the fish from the streams! Think of the sacrilege! The bright-tinted trout offered up upon the ignoble altar of calf-skin, sheepskin, and cow-skin! It boots nothing to protest against the infamy, or, "O! ye gods and little fishes!" we would summon the venerated shade of our beloved Walton, to share our indignation at the shameful innovation. Let us then pass the filling tanneries without even a requiescat in pace, and again springing and stumbling from rock to rock, and from log to log, make our way up the stream. The brook which now comes in from the ravine on the right, is that which we have already followed in our descent from the High Falls—near the Mountain House—to the Clove. We pass it by now, and advance upon the other branch. The rest of our way is as novel and romantic in its continually changing revelations, as it is arduous in achievement. Here is the favorite studio of the many artists, whom the summer months always bring to the Catskills. Nowhere else do they find, within the same narrow range, so great and rich a field for study. Every step is over noble piles of well-marked rocks, and among the most grotesque forest fragments; while each successive bend in the brook discloses a new and different cascade. The total absence of a nomenclature prevents any successful attempt to individualize the many fine points here, until we reach the base of the last and highest of the cascades, the Little Falls, to which we have already referred as having excited the jealousy of good Peter Schutt, the Prospero of the "High Falls." Often in these wild glens have we looked upward, where— "Higher yet the pine-tree hung  Or we have gazed below, where— Rock upon rock incumbent hung; With Uncle Joe as a guide, and accompanied by two of our friends, we took our first walk up this devious path, resolute in purpose and step as the youth who "bore the banner with the strange device." We sallied forth in high glee on that lovely morn, "with health on every zephyr's wing;" and even Uncle Joe failed to look upon it as "most onaccountable," when one of our party vented his superabundant enthusiasm in a recitation of Mrs. Ellis's verses: "Were I a prince, it is not all As we trudged joyously along, our chat fell upon the comparative charms of Nature, in her varying aspects, with the seasons' change. One loved the fresh and sparkling emeralds of spring, and her pure and buoyant airs; another rejoiced and dreamed happy dreams, fanned by the warmer and more soothing breezes of summer; while a third reveled in the fanciful and gorgeous appareling of motley autumn—in the rainbow beauty of the forest leaves. Uncle Joe listened with truthful sympathy to all their varying preferences; but he thought the terrors of winter, when the fathomless depths of snow buried the hills, and the giant stalactites of ice sentineled their narrow passes—the "most onaccountable." "You should see," said be, as we stood beneath the towering rocks of Little Falls, "you should see those thousand rills, trickling and leaping down so merrily from the summit of the mountain, as they appear in winter, in the shape of glittering icicles a hundred feet in length' You should look upon those waters when bitter frosts have chilled them with their own icy monuments." As our worthy thus discoursed, though in more homely phrase, the fanciful poem of Bryant suggested by similar scenes at the Mountain House Cascades, came to our mind: "'Midst greens and shades the Catterskill leaps But when in the forest, bare and old, From the top of the Little Falls, we have a noble view of the gorge of the Kauterskill, with the distant glimpse of the valley of the Hudson, and the remote plains of Connecticut. "There," as Miss Martineau writes, " where a blue expanse lies beyond the triple range of hills, are the churches of religious Massachusetts, sending up their Sabbath psalms—praise which we are too high to hear, while God is not." Half a dozen miles onward, we may enter the "Stony Clove," a pass in the western chain of these hills, generally known as the Shandaken Mountains. This gorge had been described to us as one of sublime beauty; so narrow as scarcely to admit of the passage of more than a single file of voyagers; and with such mighty walls as to exclude the faintest beam of sunshine; while ice and snow were to be seen there at all seasons of the year. Our experience afterward corrected this report. Compared with other regions of the Catskills, we thought the Stony Clove extremely monotonous; and indeed we found ourself at the other extremity, while we were yet vainly awaiting a realization of our magnificent expectations. There is a lakelet in this pass from which a certain author once drew a trout weighing five pounds; but in a second edition of his travels he reduced the extraordinary fish—at our particular and most conscientious request—to a tonnage of a pound and a half!

Before we take our leave of those hills, we must go back a while to the Kauterskill, and ascend those giant spurs looking down into its glens—the lofty Round Top and the illustrious High Peak. From these grand elevations the Mountain House and its soaring

perch are seen far, far below in the valley. Glorious are the

vistas of plain and river opened here and there in the great forests,

which shelter you in all your long ascent. When the dawning is

auspicious, you may gaze in wonder as upon a vast expanse of ocean,

with the surface here and there writhing in mad billows: now it

is a frozen sea, with huge heaps of snow-drift, which anon is

rent into mighty squadrons of giant icebergs. Magical is the effect

of the sunbeams upon this great sea of mist, making it a Proteus

in form, and a chameleon in color. Once, after passing an adventurous

night with a large and merry party of dames and cavaliers, upon

the proudest heights of the High Peak, we watched such a scene

as this until the sun, rising high in heaven, bathed farm and

cot below in the full effulgence and glory of the day. We can

not perhaps better amuse our readers than with some account of

this same memorable expedition. To this end we shall venture to

draw at pleasure, as we have already done throughout this paper,

upon letters and descriptions of the Catskills which we have written

for other occasions than the present. Gazing from the window of

our little hostelry, in the mountains, one sunny mom in July,

as the sound of many wheels struck upon our ears, we beheld a

suite of carriages, heavily laden with fair dames and gallant

lords, bent, as was evident from their excess of glee and basketry,

upon a frolic of some sort. A single glance was sufficient for

much mutual recognition between the travelers and ourselves; and

as some of the party alighted to greet us, we felt that marching

orders for our idle feet had at length arrived. So it fell out

and we were speedily enrolled a full private, in the largest and

most genial expedition which ever set forth for the conquest of

"High Peak." Our troupe was to reach the head of the

Clove (the average summit of the mountains) in the carriages,

and proceed thence, on foot, six miles to the crest of High Peak,

where we were to pass the night. Preceded by our guides, laden

with stores, we made a very gallant appearance, not lessened by

the orthodox costume of both ladies and gentlemen—the former

in a demi-composite Bloomer rig. Through bush and brake, wading

in deep mosses and clambering over and under fearful rocks, we

merrily urged our way; now and then halting for a general council

of travel, by the side of the cool mountain springs. The ladies

performed the journey stoutly, until, without let or hindrance

from bears, snakes, or panthers, we rested on the crown of the

noble peak, upon a grand table-rock covered with mosses of Of the rewards of all our enterprise and trials, in the sublime spectacle of the succeeding dawn, we have already discoursed. After a very matutinal breakfast we made a successful descent, regaining the habitable globe in good condition, and with none but pleasant memories of our adventurous night on High Peak. We have less agreeable memories of our first acquaintance with Round Top, the neighboring summit, and next in elevation to the High Peak. We had been assured that from the crest of the Round Top we should be able, at least by climbing a tree, to see "all creation." But, alas! when our destination was reached, our only reward was the consciousness of duty discharged; for so thick were the forest leaves, that look which way we would, our vision was every where obstructed. We knew that "all creation" was—as we had been told—spread out beneath us, but that knowledge was merely a Tantaluscup, while creation was so effectually hidden from view. We recollected the supreme alternative of "climbing a tree;" but then, too, we remembered not only the ten miles which we had walked, but the other ten still to be trudged over in returning; and we felt ourselves much too fatigued to venture upon any rash exploit. Our feelings at that critical moment might be happily expressed by a slight parody of some lines in the soliloquy of Hamlet's uncle: "What then? what rests? And yet, what can they when one can not climb up. Here was a quandary! After lugging ourselves and our sketch-boxes to "the height of this great argument," not a glimpse could we get of all the marvelous beauties around us. Something, however, we were determined to draw, by way of memento of the visit. As good luck would have it, our eyes unanimously fell upon the picturesque figure of our guide, old Uncle Joe, as he gracefully reclined upon a moss-grown bank, filling the air with the perfumes of the fragrant weed, As he thus arrested our attention, we thought—to use again the speech of the Danish king—" all may yet be well!" Uncle Joe was a doomed man—sacrificed upon the altar of the picturesque and of High Art. Enjoining upon him the most statuesque quiet, we rapidly transferred his undying beauties to the spotless page; one assailing him in the van; a second on his flank; while a third worried his rear; until he soon fell a victim to black lead, and was carried at the point of the pencil. Thus provided with reminiscences of Round Top, we began the descent of the mountain a little more rapidly than we went up. While hurrying down the steep declivity, Uncle Joe, who led the file, overturned a hornet's nest; but the speed at which he was moving placed him beyond the Teach of the vengeful insects by the time they were fairly aroused. He shouted the alarm, but too late for the wellbeing of the next in pursuit. Those still behind hastily avoided the fatal track and escaped. While we were quizzing our fellow-traveler upon his swelled eye, incident to the warm reception given him by the hornets, Uncle Joe fell over a prostrate tree and bruised his back. Very soon after, another slipped upon a mossy rock and damaged his ankle; while we, to, save ourself from a like fall, stupidly grasped at a thorn bush, and lacerated our hands. Condoling with each other, we hobbled along, one with his hand over his smarting eye, another seeking to straighten his dorsal latitudes, a third limping heavily, and we with our digits wrapped in a white cambric. To increase the pleasures of the day, we lost the path, and after wandering hither and thither, very much befogged, finally emerged upon the turnpike, some miles further from our inn than the point at which we had left it. Here, after the fatigues of a night on High Peak, and of a day on the Round Top, we end our wanderings in the Catskills.

Ulster & Delaware | Stories Page | Railroad Extra Contents | Catskill Archive Home

This page originally appeared on Thomas Ehrenreich's Railroad Extra Website

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

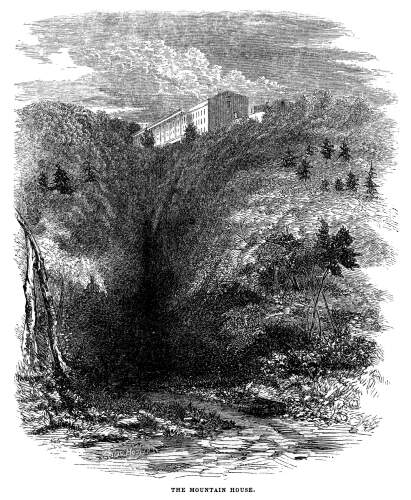

The Mountain

House is a spacious structure of wood, originally built by the

people of Catskill at a cost of more than twenty thousand dollars.

It has from time to time been since refitted and enlarged, until

it now affords all the conveniences and elegances of our most

recherche metropolitan hotels. "How the proprietor,"

says Mr. Willis, can have dragged up, and keeps dragging up, so

many superfluities from the river level to that eagle's nest,

excites your wonder. It is the more strange, because in climbing

a mountain, the feeling is natural that you leave such enervating

luxuries below. The mountain-top is too near heaven. It should

be a monastery to lodge in, so high—a St.Gothard or a Vallombrosa.

But here you choose between Hermitages, 'white' or 'red,' Burgundies,

Madeiras, French dishes and French dances, as if you had descended

upon Capua." The grand and precipitous height of the Mountain

House, reveals a scene which in extent and beauty is scarcely

rivaled by any "panoramic" view in the land. The eye

glories in a boundless sweep of cultivated champaign, sparkling

with busy towns and happy homes, bending rivers and mystic mountain

chains, between the remote hills of Vermont on the one hand, and

the dim waters of the Atlantic on the other. Miss Martineau, musing

here on a sunny, quiet Sabbath morn, thus records her impressions

of the morale of this suggestive picture:

The Mountain

House is a spacious structure of wood, originally built by the

people of Catskill at a cost of more than twenty thousand dollars.

It has from time to time been since refitted and enlarged, until

it now affords all the conveniences and elegances of our most

recherche metropolitan hotels. "How the proprietor,"

says Mr. Willis, can have dragged up, and keeps dragging up, so

many superfluities from the river level to that eagle's nest,

excites your wonder. It is the more strange, because in climbing

a mountain, the feeling is natural that you leave such enervating

luxuries below. The mountain-top is too near heaven. It should

be a monastery to lodge in, so high—a St.Gothard or a Vallombrosa.

But here you choose between Hermitages, 'white' or 'red,' Burgundies,

Madeiras, French dishes and French dances, as if you had descended

upon Capua." The grand and precipitous height of the Mountain

House, reveals a scene which in extent and beauty is scarcely

rivaled by any "panoramic" view in the land. The eye

glories in a boundless sweep of cultivated champaign, sparkling

with busy towns and happy homes, bending rivers and mystic mountain

chains, between the remote hills of Vermont on the one hand, and

the dim waters of the Atlantic on the other. Miss Martineau, musing

here on a sunny, quiet Sabbath morn, thus records her impressions

of the morale of this suggestive picture: Every fashionable

"resort" has its especial points or lions—its great

staple "sights." The staple, par excellence, of the

Mountain House is the "sunrising." Though every body

does the "sunrise," and every body rhapsodizes thereon,

and though it forms now one of our own themes, yet it never has

been and never can be looked, or talked, or scribbled up or down.

Every fashionable

"resort" has its especial points or lions—its great

staple "sights." The staple, par excellence, of the

Mountain House is the "sunrising." Though every body

does the "sunrise," and every body rhapsodizes thereon,

and though it forms now one of our own themes, yet it never has

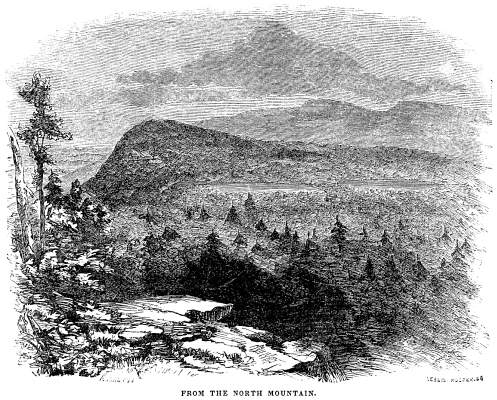

been and never can be looked, or talked, or scribbled up or down. A pleasant

morning may be spent in a tramp to the North Mountain, a neighboring

eminence, overlooking the Mountain House and its surroundings.

The "Two Lakes," of which anon, sleep peacefully below

in their soaring hammocks, while the great valley of the Hudson

spreads away to the east and south. Glorious is the sparkle and

freshness of the air at this lofty altitude, giving one a feeling

and relish of life, of a vigor and intensity undreamed of in the

thronged city. We may perhaps be permitted to relate here a little

adventure incident to our first pilgrimage to the North Mountain.

This part of the Catskills was always a favorite range of the

bear; and they may yet be readily found here when sought at the

proper season. We were duly posted in respect to this fact, as

also touching a habit this animal has of leaving marks of his

passage, in the shape of upturned stones. Our companion kept a

sharp eye upon all the rocks in our path, and seemed to be in

mortal fear of encountering one of the black gentry. It so happened

that in returning we lost our way, and the better to re-find it,

we agreed to search each in a different direction, being careful,

however, not to lose one another. We at length discovered the

path, and our fancy was so enlivened by our good fortune that

it suggested to us a little play upon the fears of our friend.

We exerted ourself successfully to overturn a number of the largest

stones around us, and then, joyfully announcing the success of

our search, we pointed with an affected shudder to the freshly

disturbed rocks. B— turned pale with fright, and grasping

us by the arm literally pulled us along the path. We intimated

to him, pointing to our sketch-box, that with such a load it would

be impossible for us to proceed so fast. Taking the hint, he added

our burden to his own, and thus relieved us to the end of the

journey. When he came to a "realizing sense" of the

nature of the ruse played upon him, which we very triumphantly

laid bare to his imagination, he vowed never again, under

any circumstances whatever, to carry our box, and at the same

time condemned us to a fine of a pitcher of the very best milk-punch

which the borough of Palenville (our headquarters at the time)

would afford.

A pleasant

morning may be spent in a tramp to the North Mountain, a neighboring

eminence, overlooking the Mountain House and its surroundings.

The "Two Lakes," of which anon, sleep peacefully below

in their soaring hammocks, while the great valley of the Hudson

spreads away to the east and south. Glorious is the sparkle and

freshness of the air at this lofty altitude, giving one a feeling

and relish of life, of a vigor and intensity undreamed of in the

thronged city. We may perhaps be permitted to relate here a little

adventure incident to our first pilgrimage to the North Mountain.

This part of the Catskills was always a favorite range of the

bear; and they may yet be readily found here when sought at the

proper season. We were duly posted in respect to this fact, as

also touching a habit this animal has of leaving marks of his

passage, in the shape of upturned stones. Our companion kept a

sharp eye upon all the rocks in our path, and seemed to be in

mortal fear of encountering one of the black gentry. It so happened

that in returning we lost our way, and the better to re-find it,

we agreed to search each in a different direction, being careful,

however, not to lose one another. We at length discovered the

path, and our fancy was so enlivened by our good fortune that

it suggested to us a little play upon the fears of our friend.

We exerted ourself successfully to overturn a number of the largest

stones around us, and then, joyfully announcing the success of

our search, we pointed with an affected shudder to the freshly

disturbed rocks. B— turned pale with fright, and grasping

us by the arm literally pulled us along the path. We intimated

to him, pointing to our sketch-box, that with such a load it would

be impossible for us to proceed so fast. Taking the hint, he added

our burden to his own, and thus relieved us to the end of the

journey. When he came to a "realizing sense" of the

nature of the ruse played upon him, which we very triumphantly

laid bare to his imagination, he vowed never again, under

any circumstances whatever, to carry our box, and at the same

time condemned us to a fine of a pitcher of the very best milk-punch

which the borough of Palenville (our headquarters at the time)

would afford. On the opposite

side of the hotel is another grand lookout which visitors delight

in, under the programme of a jaunt to the South Mountain. It overlooks

the clove of the Kauterskill, the finest chapter of the Catskill

scenery, and which we shall read con amore, when we have sufficiently

glanced at the Mountain House localities.

On the opposite

side of the hotel is another grand lookout which visitors delight

in, under the programme of a jaunt to the South Mountain. It overlooks

the clove of the Kauterskill, the finest chapter of the Catskill

scenery, and which we shall read con amore, when we have sufficiently

glanced at the Mountain House localities. The footpath

to the Falls is another and much shorter one than the carriage

way. It leaves the lakes to the right and traverses the forest.

We did it for the first time by moonlight, after lingering too

long in the shadows of the ravines below. The density of the leafage

made the way very sombre. Late rains had left innumerable pools

here and there, and our foot often sank into their treacherous

depths, when we thought we were firmly stepping upon inviting

bits of polished rock. Now we nearly lost our equilibrium, as

like a drunken roan we made a lofty step over some nothing, which,

in the partial obscurity, appeared to be a considerable obstruction

in the path. Now a dripping bough cooled our perspiring phiz with

its saucy greetings, and then our thoughtless heel crushed the

head of some unsuspecting reptile. It was a lonely walk, and despite

our romance, we were not a little relieved when we emerged from

the wilderness upon the larger path which leads over the plain

of the "Pine Orchard" to the Mountain House. The sight

of that beautiful structure, in its wild insulation, and with

its many illumined windows, obscured only by the passings and

repassings of gentle forms, was as grateful to our eye as was

the sound of the distant music to our ear.

The footpath

to the Falls is another and much shorter one than the carriage

way. It leaves the lakes to the right and traverses the forest.

We did it for the first time by moonlight, after lingering too

long in the shadows of the ravines below. The density of the leafage

made the way very sombre. Late rains had left innumerable pools

here and there, and our foot often sank into their treacherous

depths, when we thought we were firmly stepping upon inviting

bits of polished rock. Now we nearly lost our equilibrium, as

like a drunken roan we made a lofty step over some nothing, which,

in the partial obscurity, appeared to be a considerable obstruction

in the path. Now a dripping bough cooled our perspiring phiz with

its saucy greetings, and then our thoughtless heel crushed the

head of some unsuspecting reptile. It was a lonely walk, and despite

our romance, we were not a little relieved when we emerged from

the wilderness upon the larger path which leads over the plain

of the "Pine Orchard" to the Mountain House. The sight

of that beautiful structure, in its wild insulation, and with

its many illumined windows, obscured only by the passings and

repassings of gentle forms, was as grateful to our eye as was

the sound of the distant music to our ear. and when your quarter's

worth of cascade is spent, you may remount the steps to the summit

of the Fall, or may accompany us and the stream down the ravine

to the great clove below. One moment, though, before we tumble

through brush and brake. and over rock and rapid. On one occasion,

while we were sketching the beauties of certain other cascades

in the neighborhood called Little Falls, we were discovered by

Peter Schutt, who accused us bitterly of forgetting our first

love, and strictly forbade us, or any body, to "paint the

Little Falls bigger than his!" Peter Schutt can bear no rival

near the throne.

and when your quarter's

worth of cascade is spent, you may remount the steps to the summit

of the Fall, or may accompany us and the stream down the ravine

to the great clove below. One moment, though, before we tumble

through brush and brake. and over rock and rapid. On one occasion,

while we were sketching the beauties of certain other cascades

in the neighborhood called Little Falls, we were discovered by

Peter Schutt, who accused us bitterly of forgetting our first

love, and strictly forbade us, or any body, to "paint the

Little Falls bigger than his!" Peter Schutt can bear no rival

near the throne. After the passage of a mile and

a half you cross the creek on a wooden bridge, rickety and insecure

enough for all the requisitions of the picturesque, at the favorite

point of" High Rocks." Beneath this bridge is a fall

of great extent and beauty. To see it to advantage, you must hunt

up the footpath, which will lead you to the edge of the water

on the opposite bank, where a good granite lounge looks the roystering

spray full in the face.

After the passage of a mile and

a half you cross the creek on a wooden bridge, rickety and insecure

enough for all the requisitions of the picturesque, at the favorite

point of" High Rocks." Beneath this bridge is a fall

of great extent and beauty. To see it to advantage, you must hunt

up the footpath, which will lead you to the edge of the water

on the opposite bank, where a good granite lounge looks the roystering

spray full in the face. He once undertook to pilot

us over a short cut to the Mountain House, when he completely

lost his way, yet found every consolation in the reflection that

it was "most onaccountable!"

He once undertook to pilot

us over a short cut to the Mountain House, when he completely

lost his way, yet found every consolation in the reflection that

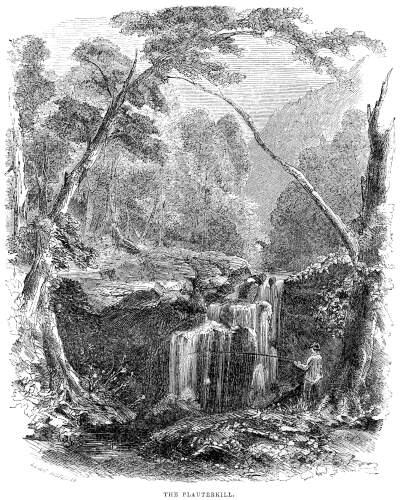

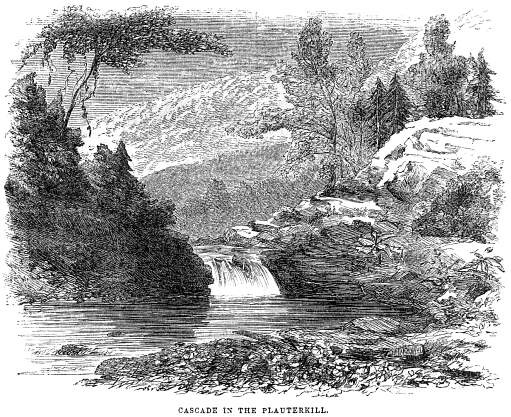

it was "most onaccountable!" Plauterkill,

the second of the two great cloves of the Catskills, is entered

five miles south of Palenville It is scarcely less fruitful in

the picturesque than is the Kauterskill; while it retains yet

more of its native luxuriance and wildness. The hand of man, however,

is now busy in its forest haunts—felling the royal tree obstructing

its foaming torrents, and winding the smooth and trodden path

through its fastnesses. The stream which makes its rugged way

in the gorge of the Plauterskill, falls, in the passage of two

miles, no less than twenty-five hundred feet. Its banks rise in

colossal mountain walls, towering high in air, and groaning with

all their mighty strength, beneath the weight of their dense forests.

A monarch among these hills is South Peak, with its crown lifted

four thousand feet toward heaven. It is full of remarkable localities,

each enwrapt in legendary lore. Not the least lovely of its possessions

is a gentle lake, perched in solitude upon its summit.

Plauterkill,

the second of the two great cloves of the Catskills, is entered

five miles south of Palenville It is scarcely less fruitful in

the picturesque than is the Kauterskill; while it retains yet

more of its native luxuriance and wildness. The hand of man, however,

is now busy in its forest haunts—felling the royal tree obstructing

its foaming torrents, and winding the smooth and trodden path

through its fastnesses. The stream which makes its rugged way

in the gorge of the Plauterskill, falls, in the passage of two

miles, no less than twenty-five hundred feet. Its banks rise in

colossal mountain walls, towering high in air, and groaning with

all their mighty strength, beneath the weight of their dense forests.

A monarch among these hills is South Peak, with its crown lifted

four thousand feet toward heaven. It is full of remarkable localities,

each enwrapt in legendary lore. Not the least lovely of its possessions

is a gentle lake, perched in solitude upon its summit. extraordinary length,

and of the softest texture. The promised land thus gained, we

set about selecting a site for our camp, which we formed under

the ledge of our trysting rock. Then what an industrious colony

we were, to be sure!—some felling trees for the construction

of the castle, others gathering mosses and hemlock sprigs for

roofing and bedding, building fires, boiling coffee, and other

preparations for the evening meal and the night's repose. All

this while a heavy storm, which had been long gathering, threatened

momentarily to break upon us, in anger at our bold invasion of

cloud-land. Night grew apace, and the newly risen moon hid herself

in affright: nearer and louder boomed the deep thunder, and more

fiercely and frightfully flashed the lightning, until our huge

campfires looked dim and pale in the electric glare. The bough-house,

which we had fully completed, was soon crowded, in the vain hope

of shelter. The water quickly penetrated its dense roof of leaves,

until every devoted noddle served as a rock for the gambols of

a mischievous little cascade. It was soon found to rain harder

inside than without, those exposed to the full blast of the storm

having the heat of the fires as an antidote. Thus passed a long

hour, when the storm, wearied with our obstinate resistance, took

itself off, with the whole baggage of mist and cloud. The moon

again gleamed forth, decking the dripping forest leaves with pearl

and diamond. The scene which followed, as one after another emerged

from the bower, and gathered around the fires to dry, was grand

and solemn in the extreme. The artists of our party made—as

artists always will—good use of the occasion. Each strove

to rival the other in excess of caricature; but no exaggeration

could exceed the reality. We had no idea that we possessed so

large a stock of dry goods (wet goods we mean), until we beheld

the vast array of submerged beaver, dripping broad-cloth, and

innundated muslin and linen, steaming on rock and bough. As it

was deemed unsafe to sleep after the rain, we were reduced to

the necessity of sitting up throughout the night, an alternative

which proved, however, to be no great hardship. Each member of

the party seemed to feel the necessity of being more than usually

amiable, and all discomfort was quickly exorcised by the magic

wand of cheerfulness. Story and jest and song followed rapidly,

and none were permitted to take cold, either physically or mentally,

by remaining quiet and unoccupied. Among our divertissements, a series of grand tableaux vivants had eminent success.

For the drama of Pocahontas and Captain Smith, the party—especially

the ladies—were already in admirable costume; and with the

wild glare of the fires, and the ghostly forest back-ground, the

representation was very tragic.

extraordinary length,

and of the softest texture. The promised land thus gained, we

set about selecting a site for our camp, which we formed under

the ledge of our trysting rock. Then what an industrious colony

we were, to be sure!—some felling trees for the construction

of the castle, others gathering mosses and hemlock sprigs for

roofing and bedding, building fires, boiling coffee, and other

preparations for the evening meal and the night's repose. All

this while a heavy storm, which had been long gathering, threatened

momentarily to break upon us, in anger at our bold invasion of

cloud-land. Night grew apace, and the newly risen moon hid herself

in affright: nearer and louder boomed the deep thunder, and more

fiercely and frightfully flashed the lightning, until our huge

campfires looked dim and pale in the electric glare. The bough-house,

which we had fully completed, was soon crowded, in the vain hope

of shelter. The water quickly penetrated its dense roof of leaves,

until every devoted noddle served as a rock for the gambols of

a mischievous little cascade. It was soon found to rain harder

inside than without, those exposed to the full blast of the storm

having the heat of the fires as an antidote. Thus passed a long

hour, when the storm, wearied with our obstinate resistance, took

itself off, with the whole baggage of mist and cloud. The moon

again gleamed forth, decking the dripping forest leaves with pearl

and diamond. The scene which followed, as one after another emerged

from the bower, and gathered around the fires to dry, was grand

and solemn in the extreme. The artists of our party made—as

artists always will—good use of the occasion. Each strove

to rival the other in excess of caricature; but no exaggeration

could exceed the reality. We had no idea that we possessed so

large a stock of dry goods (wet goods we mean), until we beheld

the vast array of submerged beaver, dripping broad-cloth, and

innundated muslin and linen, steaming on rock and bough. As it

was deemed unsafe to sleep after the rain, we were reduced to

the necessity of sitting up throughout the night, an alternative

which proved, however, to be no great hardship. Each member of

the party seemed to feel the necessity of being more than usually

amiable, and all discomfort was quickly exorcised by the magic

wand of cheerfulness. Story and jest and song followed rapidly,

and none were permitted to take cold, either physically or mentally,

by remaining quiet and unoccupied. Among our divertissements, a series of grand tableaux vivants had eminent success.

For the drama of Pocahontas and Captain Smith, the party—especially

the ladies—were already in admirable costume; and with the

wild glare of the fires, and the ghostly forest back-ground, the

representation was very tragic.