|

THE ROUTE OF THE WILD IRISHMAN.

Harper's Monthly—1887

by William H. Rideing

THIS wild Irishman is the fast train which carries the American

mails from London to Holyhead, en route to Dublin and Queenstown.

It drives down from Euston to Chester at a speed of forty miles

or more an hour, and issuing from that quaint, gabled, and galleried

city through a gap in the splendid walls, it continues on its

course to Holyhead along the picturesque shores of North Wales.

Many Americans travel by it, as in leaving or in joining the

Atlantic steamer at Queenstown they can save several hours by

taking this route, but it is usually night when they are borne

along, and the journey finds no dwelling-place in their memories.

They miss the long reaches of solidly built seawall which the

high tides of the Dee bespatter and gnaw at; and while propping

up their weary heads, and striving to shut their senses to the

jolt and jar of the train, they are unconsciously flying under

the embattlements of historic castles, along the base of sea-washed

mountains, and through the great iron tube which bridges the Menai

Strait. Precipitous cliffs frown down upon the meteor-like train:

on one side are the stormy waters of the St. George’s Channel,

and on the other the mountains descend without any intervening

foot-hills; but by means of tunnels, embankments, and viaducts

every natural obstacle in the route of the Wild Irishman has been

overcome.

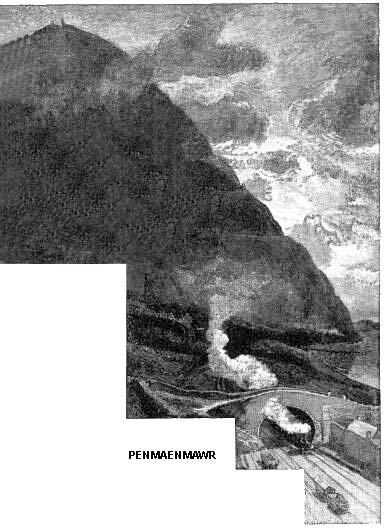

The distance between Chester and Holyhead is accomplished in

less than two hours; a tubular bridge spans the Menai Strait,

the ferrying of which formerly led to many tragedies; another

bridge is hung over the Conway River, and Penmaenmawr is pierced

by a tunnel, through which the train winds like a ring through

the nose of a savage.

When the train leaves Chester it almost immediately crosses

the boundary line between Cheshire and North Wales, and for the

rest of the distance to Holyhead it is in that country. The Dee

is visible out of the carriage windows, like a brazen serpent

crawling over a desert of mud and sand. At high-water the whole

space between the banks is overflowed, but as the ebbing tide

withdraws it only leaves a winding rivulet, which is of little

use to any except the smallest craft. Once the river was wide

and deep, but the channel has been shoaled by the washings of

the hills, and the traffic which belonged to the Dee has sought

the Mersey. Only a narrow tongue of land which Cheshire thrusts

out separates the two rivers, and a little below Chester we can

see from the windows of the Wild Irishman the place where they

meet and mingle.

On the other side of the train lies a country of increasing

hilliness—a landscape like that of England, with trim hedgerows,

thatched cottages, and the solid-looking, sculpturesque foliage

which is a sort of atonement for the persistent humidity of the

climate. Hawarden, Mr. Gladstone’s seat, is about two miles

off the line, and about twenty minutes after leaving Chester the

train runs close against the walls of Flint Castle—a gaunt

mass of naked rock, upon which decay has set no sign of regret,

and age has put no assuaging mantle. The castle was built by Edward

I., and Shakespeare has made its "rude ribs" and "tattered"

battlements one of the scenes in his play of Richard II.

Behind the hills which slope down to Flint is Holywell, a town

which derives its name from a miraculously copious spring, of

such efficacy in healing that the beautiful gothic shrine built

over it, and ascribed to the generosity of the mother of Henry

VII., is hung with the crutches and trusses of those who have

been cured by bathing in it.

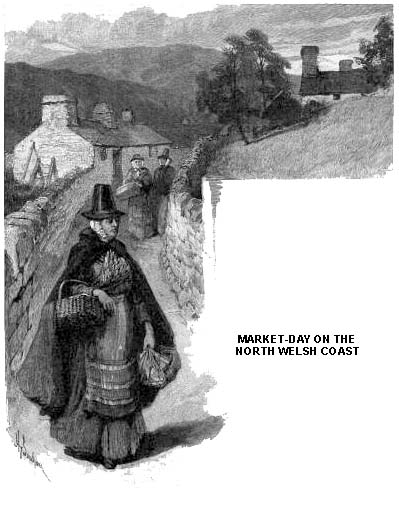

Beyond Holywell and Mostyn nearly every village along the coast

aspires, with some success, to be a watering-place. The climate

is salubrious, but how bleak, how Novemberish, to us who have

just escaped from the Senegambian fervor of the American July!

The thermometer is down below 60 degrees, but the women are dressed

in muslins and poplins, and the children, digging and building

in the sands, are bare-legged and bare-shouldered.

The Wild Irishman scarcely slackens its speed at, Rhyl, the

flat and rectangular little watering-place whose noisy excursionists

from Lancashire and Yorkshire bathe in a yellow mixture of mud

washed down from the Dee and the Mersey, and we also will pass

it by, leaving it, with Abergeley, Llandulas, and Colwyn Bay,

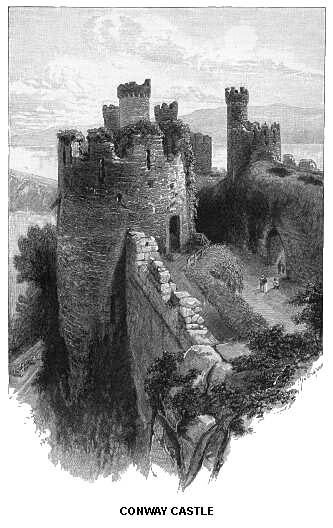

to tourists who have time to see the coast in detail. But presently

we cross a river which, flowing down from between high hills,

empties into the sea within sight of the train, at a point where

a massive headland juts outward, and reaching the farther side,

we are borne under the shadow of a cliff-like wall. We look out

and up, and there are towers, battlements, and parapets. These

are so high, and the train is so close to the base, that we have

to almost dislocate our neck in order to see the summit. It is

a castle, not a cliff; but it seems to grow out of the rock upon

which it stands, and when it was built nature and art joined hands

to give it a double strength.

When Edward

I. had conquered the Welsh he built three great castles to keep

the vanquished down, and though dismantled and despoiled, they

are still very substantial examples of the architecture of his

time: one is at Carnarvon, another at Beaumaris, and the third

is this at Conway, the common name of the river which we have

just crossed, the castle, and the little town which lies under

the castle, shut within a harp-shaped wall which formerly had

twenty-four round towers. When Edward

I. had conquered the Welsh he built three great castles to keep

the vanquished down, and though dismantled and despoiled, they

are still very substantial examples of the architecture of his

time: one is at Carnarvon, another at Beaumaris, and the third

is this at Conway, the common name of the river which we have

just crossed, the castle, and the little town which lies under

the castle, shut within a harp-shaped wall which formerly had

twenty-four round towers.

We are disposed to take Pennant’s word when that antiquary

declares Conway to be the most beautiful of fortresses. The form

is oblong, placed in all parts on the verge of precipitous rock.

One side is bounded by the river, one by a creek which fills with

every tide, and the other two face the town. Within are two courts,

around which are the various apartments, or what remains of them.

But the banqueting hall has tumbled into the kitchen, and the

Queen’s boudoir is scarcely recognizable from the dungeon

cell. No roof or rafters remain, and the grass grows on the floor

of the Council Chamber. The cold wind rushes through the empty

fireplaces, the windows have nothing in them except the vines,

and the winding stairways only go up a few steps, and then leave

us standing on the brink of some ragged gap. Ivy, moss, and grass

have taken hold even of the highest towers, and the only pomp

is the pomp of age.

We look at the smooth river issuing between the hills to the

sea, and the quaint town and its little houses shut within the

triangular walls. That headland of which we have spoken once or

twice is the Great Orme’s-Head, one of the most conspicuous

points to all vessels passing up and down the channel, and between

it and a similar though smaller elevation we can see some of the

roofs of Llandudno, one of the most delightful of watering-places.

But all other things are dwarfed in comparison with Penmaenmawr,

which now looms up, and we can pity the travellers who, before

the days of the Wild Irishman, found this shoulder of rock—a

very cold shoulder indeed—thrust in their way.

Change is visible everywhere about the castle, and some thrifty

husbandman is raising cabbages and potatoes in the moat. Other

parts of the grounds are also turned to account as vegetable gardens,

and the gate has no more formidable guard than a little girl in

a blue pinafore. But while we sat eating our luncheon at the inn

adjoining the castle we were reminded that though the relics of

mediæval chivalry belong to museums, the love of military

glory is still as strong in the female breast as it was before

the watch on the ramparts had become a noiseless spectre. The

little waitress was in a flutter of intense excitement. Some Volunteers,

with faces as red as their uniforms, who had been encamped outside,

were leaving the town, and she was divided between her anxiety

to be attentive to us and her desire to look out of the window

at them. "Will you have some cheese, sir?" "Yes,

ma’am; they’re the Volunteers." She tried hard

to control herself, but she was carried away in her ecstasy, and

we saw her run to the window and bring her hands together as if

to applaud. Her pink face beamed, and the ribbons in her lace

cap danced. " Oh, if you please, ma’am, doesn’t

the band play lovely!" she exclaimed, in a burst of rapture;

and then she looked frightened, and hurried back to the table

to give us our coffee.

A minute or

two after the train leaves Conway the mountains begin to crowd

down upon the Wild Irishman, and threaten to shove the line into

the sea. It is these that the traveller from America sees from

the deck of the ocean steamer as she passes up the St. George’s

Channel to Liverpool. They are a northern spur of the Snowdon

range, and among the huddled masses rises one, a very Gibraltar

of a peak, higher than all the rest. This, which strangers often

mistake for Snowdon itself, is Penmaenmawr, the via mala

of the old route to Holyhead, upon which many a traveller has

come to grief between the crumbling strata of the mountain on

one side and the unprotected precipice on the other. The road

was grooved in the mountain, and, says Nicholson, writing of it

as it was before the day of the Wild Irishman: "The amazingly

abrupt precipice, variegated with fragments and ruins, presents

a scene of horror. In some places rocks of vast magnitude, which

have probably fallen from the summit, lodge on projecting ledges,

and appear in the act of taking another bound." But carried

along by this fast train, we have only the momentary darkness

of a tunnel to remind us of what Penmaenmawr was a century ago.

The Wild Irishman stops nowhere, not even at the little cathedral

city of Bangor, and it hurries us on to the, Menai Strait, which

resembles the Hudson at Tarrytown. Villas and cottages are visible

everywhere, and building sites are held at a very high price. A minute or

two after the train leaves Conway the mountains begin to crowd

down upon the Wild Irishman, and threaten to shove the line into

the sea. It is these that the traveller from America sees from

the deck of the ocean steamer as she passes up the St. George’s

Channel to Liverpool. They are a northern spur of the Snowdon

range, and among the huddled masses rises one, a very Gibraltar

of a peak, higher than all the rest. This, which strangers often

mistake for Snowdon itself, is Penmaenmawr, the via mala

of the old route to Holyhead, upon which many a traveller has

come to grief between the crumbling strata of the mountain on

one side and the unprotected precipice on the other. The road

was grooved in the mountain, and, says Nicholson, writing of it

as it was before the day of the Wild Irishman: "The amazingly

abrupt precipice, variegated with fragments and ruins, presents

a scene of horror. In some places rocks of vast magnitude, which

have probably fallen from the summit, lodge on projecting ledges,

and appear in the act of taking another bound." But carried

along by this fast train, we have only the momentary darkness

of a tunnel to remind us of what Penmaenmawr was a century ago.

The Wild Irishman stops nowhere, not even at the little cathedral

city of Bangor, and it hurries us on to the, Menai Strait, which

resembles the Hudson at Tarrytown. Villas and cottages are visible

everywhere, and building sites are held at a very high price.

Once again we are in darkness, but this time the reverberations

are not those of a tunnel. The sounds are hollow and metallic;

we are crossing the strait by the vast tubular bridge Which Stephenson

built between 1846 and 1850, and which put an end to the frequent

accidents that had previously occurred to passengers crossing

by the ferry. The Britannia Bridge, as it is called, consists

of eight tubes resting on three towers, and it spans the stream

at a height of 104 feet. It is 1841 feet long, and the tubes are

said to contain 11,400 tons of iron. Some fellow passenger is

sure to put us in possession of these dimensions, but we who have

seen the Brooklyn Bridge can listen unmoved, and give him in return

the statistics of a much greater achievement.

One end of the bridge—that by which we enter—is in

Carnarvonshire, and when we reach the other we are in the island

of Anglesey, the Mona of early English history, and the last refuge

of the Druids. It is not a very large island, only twenty miles

from north to south, and twenty-eight miles from east to west.

The surface is rolling and (if such a word can be employed to

describe anything in nature) commonplace, but, except in the straits,

the seaward edge is a long line of cliffs of varying height, at

whose feet many a ship has come to grief. There are many Druidical

remains on the island, cromlechs and other enigmatical masses

of stone which the old hierarchy of the woods has left unexplained,

and it was in Anglesey that Suetonius burned the last of the Druids

in their own altar fires. Tacitus has painted the wild scene which

opened upon the Roman forces when they landed: the motley army

in close array and well armed, with women running frantically

about, their dishevelled hair streaming in the wind, while they

brandished torches in their hands, and the priests moving among

them, and, with arms reached out to heaven, uttering the most

awful curses on the invaders. The Roman soldiers were spellbound,

and for some time were, as Tacitus puts it, resigned to every

wound; but at length, aroused by their leader, and calling on

one another not to be intimidated by a womanly and fanatic band,

they displayed their ensigns, and quickly hushed their antagonists.

Anglesey has another claim to remembrance, as the home of the

founder of the Tudor dynasty, who danced so well that he won the

heart of the fair widow of Henry V. The queen, says an old chronicler,

" beyng young and lustye, followyng more her own appetyte

than frendely consaill, and regardyng more her private affection

than her open honour, toke to husband privily a goodly gentylman,

and a beautiful person, garnized with manye godly gyftes, both

of nature and of grace, called Owen Teuther, a man brought forth

and come of the noble linage and auncient lyne of Cadwalader,

the last Kynge of the Britonnes." Some courtiers who were

sent to Wales to ascertain the condition of the Tudors found Owen’s

mother seated in a field with her goats around her; but there

is no doubt that, though reduced in circumstances, the family

was of high descent.

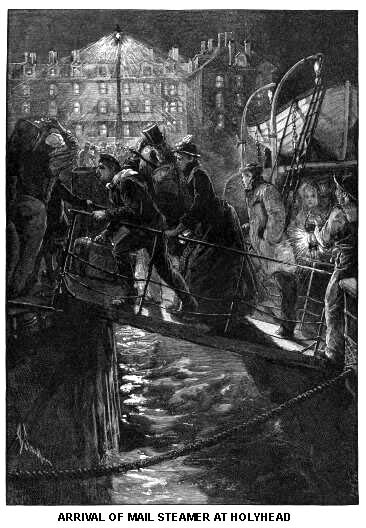

A few miles

from Holyhead we pass within a short distance of Aberffraw, the

seat of the native princes of Wales, and thus the Wild Irishman

completes its course, and lands us at the gangway of the channel

steamer. The lugubrious passage is not for us this time; and knowing

what it is, we watch the other passengers embark with feelings

of pity. It is not an affair of eighty or ninety minutes, like

that from Dover to Calais, or from Folkestone to Boulogne. It

takes fully five hours, and the sea gives the steamer that irregular,

eccentric motion which nothing can resist. It is a gusty and rainy

expanse, and it is seldom peaceful or sunny. Few who have made

it think of it except with abhorrence, and to recall it is to

have visions of wet and slippery decks, pelting showers of spray,

gray, low-hung clouds, and angry-looking waters. The steamer is

sheltered in a large masonry dock, but, looking out to the mouth

of the harbor, we can see the waves spattering over the breakwater,

and a sallow-hued anticipation of discomforts to come is visible

in the faces of those who are stumbling down the narrow gang-plank.

There are members of Parliament, government messengers, sportsmen,

tourists, and commercial travellers. There are few English people,

but many Americans, who could be identified by their enormous

iron-clad trunks if they were not individualized in other ways.

The transfer from the train to the boat is quickly effected. Saratogas,

knapsacks, gun-cases, fishing-rods, bicycles, and despatch-boxes

are rushed on board after the passengers, and then the mail is

heaped upon the deck. The bags are lettered with the names of

American cities, and while we are speculating on their contents

the little steamer starts, and in a very few minutes passes out

beyond the breakwater into the open sea. A few miles

from Holyhead we pass within a short distance of Aberffraw, the

seat of the native princes of Wales, and thus the Wild Irishman

completes its course, and lands us at the gangway of the channel

steamer. The lugubrious passage is not for us this time; and knowing

what it is, we watch the other passengers embark with feelings

of pity. It is not an affair of eighty or ninety minutes, like

that from Dover to Calais, or from Folkestone to Boulogne. It

takes fully five hours, and the sea gives the steamer that irregular,

eccentric motion which nothing can resist. It is a gusty and rainy

expanse, and it is seldom peaceful or sunny. Few who have made

it think of it except with abhorrence, and to recall it is to

have visions of wet and slippery decks, pelting showers of spray,

gray, low-hung clouds, and angry-looking waters. The steamer is

sheltered in a large masonry dock, but, looking out to the mouth

of the harbor, we can see the waves spattering over the breakwater,

and a sallow-hued anticipation of discomforts to come is visible

in the faces of those who are stumbling down the narrow gang-plank.

There are members of Parliament, government messengers, sportsmen,

tourists, and commercial travellers. There are few English people,

but many Americans, who could be identified by their enormous

iron-clad trunks if they were not individualized in other ways.

The transfer from the train to the boat is quickly effected. Saratogas,

knapsacks, gun-cases, fishing-rods, bicycles, and despatch-boxes

are rushed on board after the passengers, and then the mail is

heaped upon the deck. The bags are lettered with the names of

American cities, and while we are speculating on their contents

the little steamer starts, and in a very few minutes passes out

beyond the breakwater into the open sea.

It is then that we discover what an empty, noiseless little

place Holyhead is. It is the nearest port to Ireland, and that

is, and always has been, the reason of its existence. The harbor

is the principal part of it now, as it was years ago, when there

were no steamers, and the vessels used were small sail-boats,

which often took four or five days in making the passage between

here and Dublin. Vast sums have been spent on its beacons, and

on the long granite breakwater, the granite docks, and the lofty

sheds lighted by electricity. There are rumors that some day it

will be the terminus of a line of transatlantic steamers, which,

by using it, will avoid the fogs and tidal delays of the Liverpool

bar; but in the mean time it has the appearance of a premature

expansion. After the departure of the mail-boat it suddenly becomes

silent and sepulchrally still. The vociferous newsboy, the wharfingers,

the porters, and the railway and steam-boat officials all disappear.

The ticket-office windows are abruptly closed, and the pensive

attendant in the refreshment-room turns the lock on the mildewed

veal pies and the sawdust sandwiches, which have reminded us of

Mugby Junction. Our footsteps sound boisterously loud, and we

have a feeling of detachment and sequestration. Looking down the

harbor, we can see no movement. Half a dozen or more spare boats

are moored along the splendid piers, but they are out of service

and unmanned.

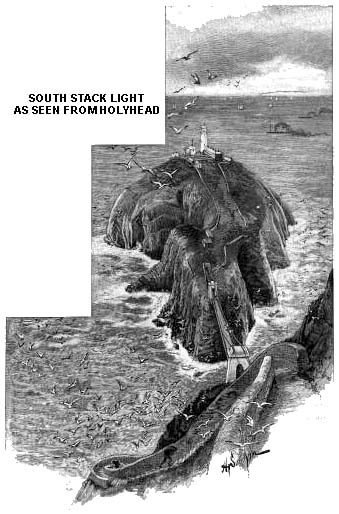

Wandering out

of the brick and granite enclosures of the modern docks, we enter

the straggling, and little town, which has a curious old parish

church dating from the reign of Edward III.; and then leaving

the crouching white cottages with the fortress-like walls behind,

we strike out in the direction of the mountain which slopes upward

to the north and west of the town, and is of such a height that

a veil of blue or purple always hangs upon it. This is Holyhead

itself, the point from which nearly all vessels passing up and

down the channel are signalled, and which is familiar to all readers

through the maritime columns of the newspapers. The slope upward

from the harbor and town forms a buttress to the wall which the

mountain presents to the sea, and from the summit we can look

down as dizzy and terrifying a precipice as there is on the coast

of North Wales. The face of the rock is scarred and seamed in

an extraordinary manner, and at its base the sea has bored several

enormous caverns and alcoves, one of which, called the Parliament

House, is seventy feet high. Our path up the slope is through

some rocky, heather-strewn fields, and then over the shoulder

of the mountain, and down a steep stairway in the cliff. The sea

reaches out before us, quivering and glinting, and down below

us rises an appalling mass of rock, linked to the mountain by

a frail suspension-bridge, and surrounded by a chain of breakers.

On all sides of us there are vertical spaces and jagged edges,

and the escarpment has a strange and crumpled look, as if it had

been torn with difficulty from some other mass by a sudden disrupting

force. On every ledge there are flocks of birds—sea-gulls,

razor-bills, cormorants, and guillemots, which whirl and sweep

around us, and add to the wildness of the scene by their unearthly

shrieks. We might suppose that no other living creatures would

be found here, but man’s ingenuity has utilized that detached

mass of rock, which, though below us, is still nearly 150 feet

above the level of the sea, and on the summit rises the white

pillar of a light-house and the neat cottages of the keepers.

The sea has cut a tunnel through it, and when the wind is high

the spray is carried over the suspension-bridge which loops the

outer cliff with the inner. But, whirl and thunder as the gale

will, the waters have never yet reached the lantern, and at night

it is visible over the whole of Carnarvon Bay, and in conjunction

with the light on the Skerries, this on the South Stack, as the

rock on which we are looking is called, guides the boat from Dublin

into the harbor, where the Wild Irishman is waiting to retrace

its way to the noisy metropolis. Wandering out

of the brick and granite enclosures of the modern docks, we enter

the straggling, and little town, which has a curious old parish

church dating from the reign of Edward III.; and then leaving

the crouching white cottages with the fortress-like walls behind,

we strike out in the direction of the mountain which slopes upward

to the north and west of the town, and is of such a height that

a veil of blue or purple always hangs upon it. This is Holyhead

itself, the point from which nearly all vessels passing up and

down the channel are signalled, and which is familiar to all readers

through the maritime columns of the newspapers. The slope upward

from the harbor and town forms a buttress to the wall which the

mountain presents to the sea, and from the summit we can look

down as dizzy and terrifying a precipice as there is on the coast

of North Wales. The face of the rock is scarred and seamed in

an extraordinary manner, and at its base the sea has bored several

enormous caverns and alcoves, one of which, called the Parliament

House, is seventy feet high. Our path up the slope is through

some rocky, heather-strewn fields, and then over the shoulder

of the mountain, and down a steep stairway in the cliff. The sea

reaches out before us, quivering and glinting, and down below

us rises an appalling mass of rock, linked to the mountain by

a frail suspension-bridge, and surrounded by a chain of breakers.

On all sides of us there are vertical spaces and jagged edges,

and the escarpment has a strange and crumpled look, as if it had

been torn with difficulty from some other mass by a sudden disrupting

force. On every ledge there are flocks of birds—sea-gulls,

razor-bills, cormorants, and guillemots, which whirl and sweep

around us, and add to the wildness of the scene by their unearthly

shrieks. We might suppose that no other living creatures would

be found here, but man’s ingenuity has utilized that detached

mass of rock, which, though below us, is still nearly 150 feet

above the level of the sea, and on the summit rises the white

pillar of a light-house and the neat cottages of the keepers.

The sea has cut a tunnel through it, and when the wind is high

the spray is carried over the suspension-bridge which loops the

outer cliff with the inner. But, whirl and thunder as the gale

will, the waters have never yet reached the lantern, and at night

it is visible over the whole of Carnarvon Bay, and in conjunction

with the light on the Skerries, this on the South Stack, as the

rock on which we are looking is called, guides the boat from Dublin

into the harbor, where the Wild Irishman is waiting to retrace

its way to the noisy metropolis.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|