FRANK LESLIE'S

POPULAR MONTHLY.

Vol. LII. JULY, 1901 . No. 3.

THE GREAT LOG JAM

BY STEWART EDWARD WHITE.

THE STORY OF ONE OF THE MOST TERRIFIC BATTLES IN THE

HISTORY

OF AMERICAN INDUSTRY.

COPYRIGHT, 1901. BY FRANK LESLIE PUBLISHING HOUSE. ALL RIGHTS

RESERVED.

AFTER saw logs are cut and hauled to the banks of a river,

they rest until the spring floods. Then they are floated to the

mills.

To accomplish this apparently simple feat a large crew is required.

The men work twelve, sixteen, even eighteen hours a day in ice

water; sleep in temporary camps; and constantly expose themselves

to a hundred dangers. One of the greatest of these is encountered

while breaking jams, which, contrary to general belief, are of

common occurrence.

In a swift stream running through an accidental bed, great

masses of logs pile up with astonishing rapidity. A little obstruction,

a sudden narrowing or shoaling of the channel, an instant's check

of any kind, at once the advance guard tumbles together, the following

timbers grind down on the obstruction thus formed; the water banking

up quickly behind the temporary dam, presses the locked pieces

immovably together. Then it becomes a question of working with

peevy, axe or even dynamite, under the sheer face of timber, until

a sudden crack! warns the rioermen that the mass is about to vomit

down on them. They escape at the last moment over the logs floating

in the slack water below the jam. A single mis-step means death.

I have seen men save their lives by diving from before a breaking

roll-way into the icy river, and allowing themselves to be carried

down stream through the rush of waters.

Ordinarily

it is expedient to break a jam as soon as possible. Once the river

begins to fall, the logs settle, and so press the more firmly

together. A very slight decrease in the volume of the water-will

lock the timber immovably. On the other hand, if the jam happens

to form between high banks, sooner or later the river will back

up sufficiently behind it to flow over it. Naturally, when this

happens, the logs on top are lifted, floated down, and precipitated

over the breast of the jam into the stream below, where they either

kill the men working at the breaking, or stick upright in the

river bottom as a further obstruction. The formation of a jam,

then, is a signal for feverish activity, and the man who is "driving"

the river never breathes freely until his logs are once more racing

down the current. Ordinarily

it is expedient to break a jam as soon as possible. Once the river

begins to fall, the logs settle, and so press the more firmly

together. A very slight decrease in the volume of the water-will

lock the timber immovably. On the other hand, if the jam happens

to form between high banks, sooner or later the river will back

up sufficiently behind it to flow over it. Naturally, when this

happens, the logs on top are lifted, floated down, and precipitated

over the breast of the jam into the stream below, where they either

kill the men working at the breaking, or stick upright in the

river bottom as a further obstruction. The formation of a jam,

then, is a signal for feverish activity, and the man who is "driving"

the river never breathes freely until his logs are once more racing

down the current.

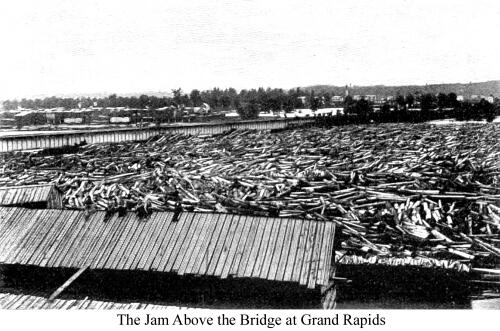

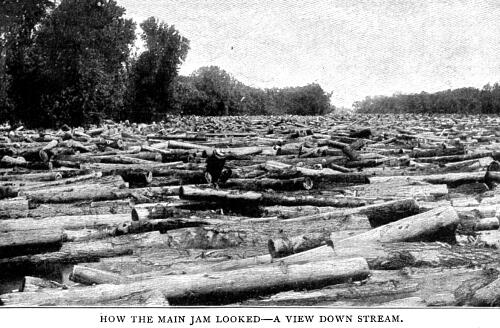

Probably the biggest jam in the history of logging occurred

in the Grand River of Michigan in the summer of 1883. It involved

over one hundred and fifty million feet of logs. It is a little

difficult to convey an idea of an hundred and fifty million feet.

Such a mass would weigh, for instance, about thirty-seven million

tons. If piled evenly ten feet high in a river bed a hundred feet

wide, it would extend about ten miles. Singularly enough tremendous

day and night efforts were put forth, not to break the jam, but

to hold it. The men in charge knew that, once this tremendous

force should get beyond control, nothing short of a miracle would

prevent it from sweeping through everything and scattering abroad

over Lake Michigan. That would mean total loss, for salvage would

cost more than the lumber was worth. As a matter of fact, the

jam did get beyond control, and such a miracle did manifest itself.

The way of it was this:—

The first intimation outsiders received of the possibility of

danger came to them on June 26th. Three of the pile-driver men

in the employ of the company which had contracted to do the driving,

asked for two days vacation in order that they might take in Barnum's

circus at Muskegon.

"Can't let you off, boys," said the bookkeeper in

reply.

At the refusal the men grumbled somewhat and loudly considered

the advisability of going anyway. One of the company's officers

here interposed.

"We need you, boys, every one of you," said he, "and

if its worth anything to you to give up your holiday, I guess

the company will make it right. We're going to have all Grand

River down on us in no time."

That evening a tug took the men back to the boom, where, early

the next morning, they and their companions began a three weeks'

struggle.

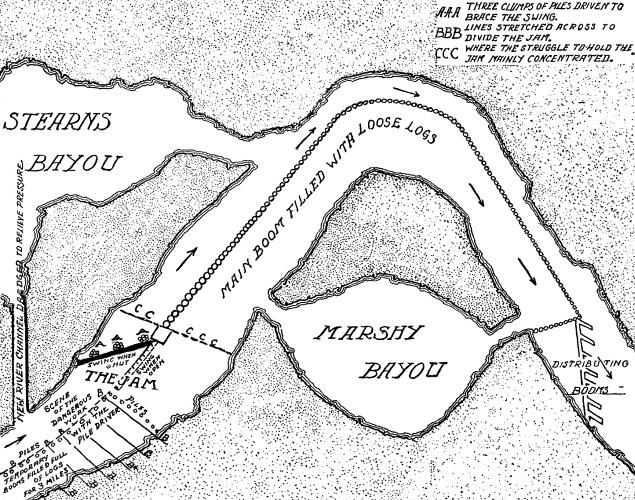

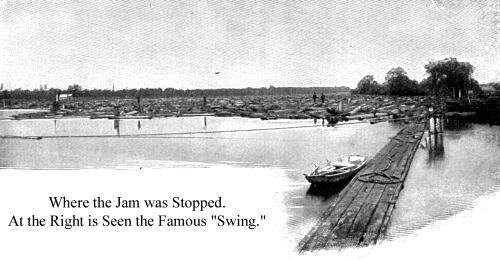

The company's

booms, or enclosures, contained about fifty millions of pine logs.

The enclosures were made of piles driven upright in the river

bottom, close together, and bound at the top by timbers bolted

strongly to either side. The main boom occupied half the channel

for a distance of two and one-half miles, and was supplemented

at the upper end by a floating swing 150 feet long, entirely closing

the river. This swing was operated by means of a winch and an

endless chain, exactly on the principle of a Harlem clothes-line

between two houses. In the narrow strip, so divided off, the logs

of all the sawmills of Nortonville, Spring Lake, Ferrysburg and

Grand Haven awaited sorting and distribution. Besides this, above

the main boom various temporary booms had been put in to accommodate

the extra amount of timber which an immediately preceding dry

season had accumulated. Immediately below was Lake Michigan and

total loss. The company's

booms, or enclosures, contained about fifty millions of pine logs.

The enclosures were made of piles driven upright in the river

bottom, close together, and bound at the top by timbers bolted

strongly to either side. The main boom occupied half the channel

for a distance of two and one-half miles, and was supplemented

at the upper end by a floating swing 150 feet long, entirely closing

the river. This swing was operated by means of a winch and an

endless chain, exactly on the principle of a Harlem clothes-line

between two houses. In the narrow strip, so divided off, the logs

of all the sawmills of Nortonville, Spring Lake, Ferrysburg and

Grand Haven awaited sorting and distribution. Besides this, above

the main boom various temporary booms had been put in to accommodate

the extra amount of timber which an immediately preceding dry

season had accumulated. Immediately below was Lake Michigan and

total loss.

When the three men reached their driver, they found that the

river had already swelled greatly in volume. Heavy rains were

partly accountable; but cloud-burst floods from Crockery Creek

district, above Grand Rapids, had rolled the streams to freshet

volume. A man stood all night on the swing, reporting at intervals

the progress of the water as it crept up the piles. By morning

it was very near the top. Men were at once set to raising the

height of the boom by tying logs firmly to the bolted timbers.

At other places the pile drivers drove strengthening buttresses

here and there where weak spots showed. Still other men stretched

from the boom piles to the shore, strong cables across the field

of logs, in order that the swift current might not jam them all

at the down-stream end of the enclosure. The cables were borrowed

of a barge company, and were of fifteen-inch manila rope.

So, although the water was boiling through at mill-race speed,

affairs were going well. The logs bound to the bolted timbers

would prevent the saw logs from jumping or flowing over the top

of the boom; the buttresses would keep them from breaking out

through the piles, and the cables would hold them, in sections,

from too great pressure below.

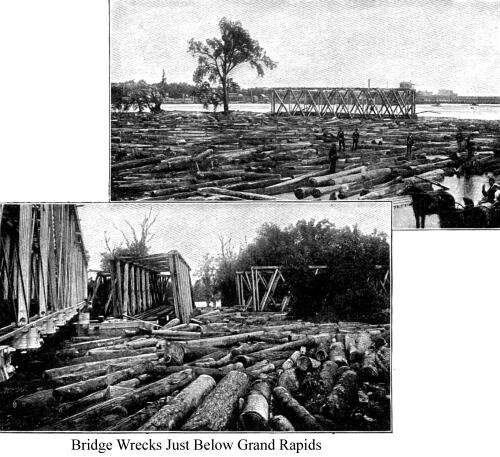

While this comforting conclusion was being reached at Grand

Haven, the Grand Rapids booms had broken, and one hundred million

feet of logs had rushed down stream to jam at the Detroit &

Milwaukee railroad bridge near Grand Rapids. Suddenly the affair

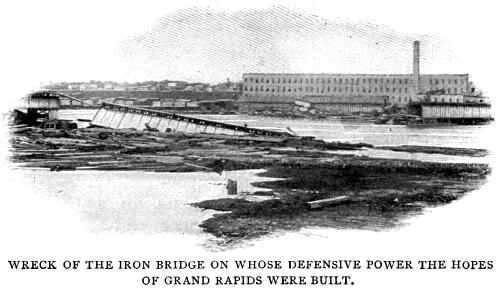

had become serious.

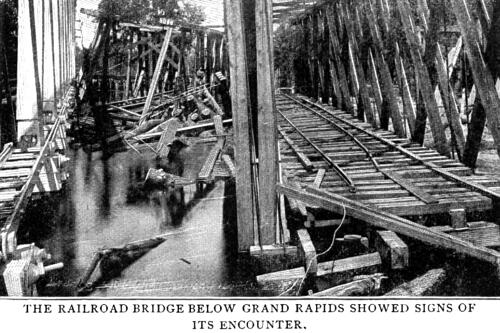

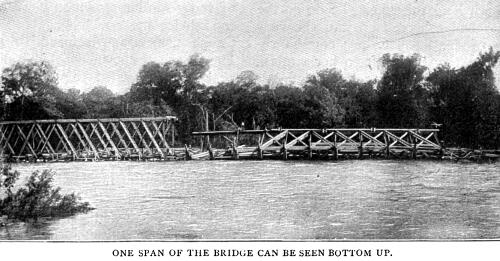

The D. & M. bridge, fortunately, was a new structure built

entirely of iron. Should it be carried out, however, nothing could

prevent the jam from sweeping away the other and lighter structures

down stream. Then it was a clear race from Grand Haven.  No one was sanguine

enough to imagine for a moment that the wooden defenses at Grand

Haven would oppose even a momentary barrier to the shock. The

result would be that all the hundred and fifty million feet of

the combined booms would sweep out into Lake Michigan, there to

be irretrievably lost. No one was sanguine

enough to imagine for a moment that the wooden defenses at Grand

Haven would oppose even a momentary barrier to the shock. The

result would be that all the hundred and fifty million feet of

the combined booms would sweep out into Lake Michigan, there to

be irretrievably lost.

The blow to the State's prosperity can hardly be estimated.

Besides a loss of some millions of dollars' worth of sawed lumber—which

would mean the failure, not only of many of the mill companies,

but also of thebankers holding their paper, and so of firms in

other lines of business—thousands of men would be thrown

out of employment; and, what was quite as serious, the destruction

of the bridges would mean the total severance of all railroad

communication between eastern and western Michigan. For a season,

industry of every description would be practically paralyzed.

The most strenuous efforts, then, were concentrated on the

new iron bridge. It was a massive structure, each of whose bents

weighed over a hundred tons. Braces of oak beams were at once

slanted where they would do the most good; chains strengthened

the weaker spots, and on top and all about ton after ton of railroad

iron held the whole immovably. It did not seem possible that any

force could stir such a mass.

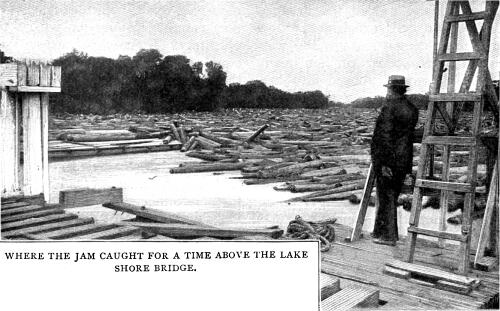

The jam extended

up river for over three miles, but fortunately floated. If it

had jammed to the bottom of the river, the water would have backed

up behind it as behind a dam; but now, luckily, the river had

a clear channel below the log's and the bridge. A slight fall

of the stream would suffice to lock the affair beyond the possibility

of accident. This fall, of a few inches only, actually occurred.

As the local paper jubilantly expressed it: "It's a hundred

dollars to an old hat she holds." The jam extended

up river for over three miles, but fortunately floated. If it

had jammed to the bottom of the river, the water would have backed

up behind it as behind a dam; but now, luckily, the river had

a clear channel below the log's and the bridge. A slight fall

of the stream would suffice to lock the affair beyond the possibility

of accident. This fall, of a few inches only, actually occurred.

As the local paper jubilantly expressed it: "It's a hundred

dollars to an old hat she holds."

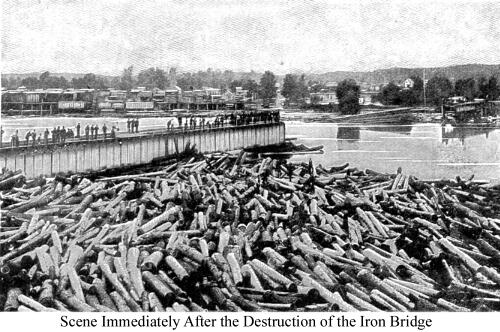

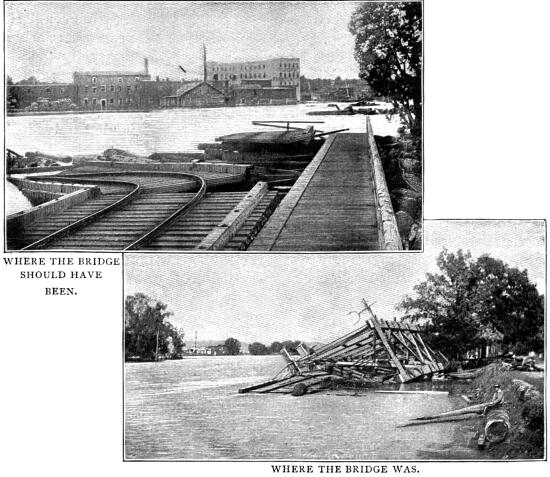

Then, without the slightest warning, in seven minutes, the

jam gathered its might and carried away the elaborate defenses

as though they had been made of straw. Old man Jinby rode frantically

into Grand Rapids, like a second Paul Revere, screaming out that

the flood had broken loose. The other railroad bridges with the

exception of the Lake Shore, did not even offer a check. Five

hours later about half of the logs boiled into sight at Grand

Haven, fifty miles away.

It is impossible to describe the excitement and consternation

that reigned in Grand Rapids as the rushing timbers shot down

the current past the city. No old-established country could ever

understand it. Destruction threatened not only men's fortunes,

but their very life-work in building up a community. As the heavy

iron bridges one after the other crumpled up like matchwood and

were borne out of sight down stream on the very top of the jam,

no one for a moment entertained the hope that anything could stop

the rush this side of Lake Michigan.

The first period

of security at Grand Haven had been of but short duration. All

that day and the following night the water had steadily risen

at the rate of an inch an hour. Soon it became evident that the

boom piles would never suffice to hold the enormous pressure when

once the full force of the freshet should bear on them. Especially

was this true of the temporary booms up stream. In order to hold

the logs from pressing against the main boom it became necessary

to shut the swing across the river. Before doing so, however,

the pile-driver started to drive three clumps of piles in the

opening, against which the swing, when shut, should rest. The first period

of security at Grand Haven had been of but short duration. All

that day and the following night the water had steadily risen

at the rate of an inch an hour. Soon it became evident that the

boom piles would never suffice to hold the enormous pressure when

once the full force of the freshet should bear on them. Especially

was this true of the temporary booms up stream. In order to hold

the logs from pressing against the main boom it became necessary

to shut the swing across the river. Before doing so, however,

the pile-driver started to drive three clumps of piles in the

opening, against which the swing, when shut, should rest.

Two of the clumps had been driven, and bound together by cables.

The third was in the process, when, with a crack and a roar, the

upper booms, giving way, projected their logs upon the opening

and the driver. Fortunately, the man in charge of the swing did

not lose his head. He succeeded in starting the long arm; the

logs, rushing in back of it, hurried it shut, jammed, and heaped

up in a formidable tangle behind the barrier.

The huge driver was lifted bodily in the air and deposited

with a crash half on the bank and half in the water.

For the moment all was safe. But the pressure had begun. Behind

the swing the logs were banked solidly to the bottom of the river,

and behind them the water gathered power every instant. Already

the main boom was feeling it. The great fifteen-inch cables tightened

slowly but mightily; some of the piles began to groan; here and

there a log up-ended across the level.

Now for four days and nights ensued a grim struggle for supremacy

that has probably never been equalled in industrial history. Twenty

million tons of logs and a river of water pushed steadily and

relentlessly; seventy-five men threw before them the ingenious

obstructions invented by determination and desperation. The pile-driver

worked day and night placing clumps, each of sixteen piles, bound

to solidity by chains, and so arranged in angles and slants as

to direct the enormous pressure toward either bank. Another drove

similar clumps here, there and everywhere that need arose. Men

stretched hawsers. Others did nothing but watch for the weakening

places. The groaning and creaking of the mass was said to be especially

terrifying—it must have been so to the devoted band who worked

without sleep under the frowning brow of destruction.

Not an instant

of those eighty-four hours was wasted. By the most tremendous

exertions the men seemed just able to keep even. It appeared that

a breathing spell would bring the deluge. Piles quivered, bent

slowly outward—at once, immediately before the logs behind

could stir, the driver must do its work. At night it was the worst.

No man could tell, while bracing one spot, how soon another might

give way to let loose his destruction. The water rose steadily;

the logs grew more and more restive, the defenses weaker and more

inadequate. Spectators marveled how the jam held, yet hold it

did, and without rest the dogged little insects under its face

toiled to gain an inch on the waters. Not an instant

of those eighty-four hours was wasted. By the most tremendous

exertions the men seemed just able to keep even. It appeared that

a breathing spell would bring the deluge. Piles quivered, bent

slowly outward—at once, immediately before the logs behind

could stir, the driver must do its work. At night it was the worst.

No man could tell, while bracing one spot, how soon another might

give way to let loose his destruction. The water rose steadily;

the logs grew more and more restive, the defenses weaker and more

inadequate. Spectators marveled how the jam held, yet hold it

did, and without rest the dogged little insects under its face

toiled to gain an inch on the waters.

So tremendous was the pressure at this time, that here and

there over the surface of the jam single logs could be seen popping

suddenly into the air, propelled as an apple seed is projected

from between a boy's thumb and forefinger. Some of the fifteen-inch

manila ropes stretched to the shore parted. One, which passed

once around an oak tree before reaching its shore anchorage, actually

buried itself out of sight in the hard wood! Bunches of piles

bent, twisted or were cut sheer off as though they had been nothing

but shocks of Indian corn. The current was so swift that the tugs

could not hold the drivers against it; and, as a consequence,

before commencing operations, especial mooring piles had to be

driven.

The excitement

was intense. Men who have served in the war tell me that the intoxication

of battle was nothing to it. In this combined the elements of

desperation and the spirit of the American pioneer bent on victory. The excitement

was intense. Men who have served in the war tell me that the intoxication

of battle was nothing to it. In this combined the elements of

desperation and the spirit of the American pioneer bent on victory.

The crew worked marvels. Few of them thought for an instant

of quitting. Once, after two nights without sleep, they began

to grumble a little. John Walsh, who had charge of No. 4 driver,

did not make the mistake of commenting or of raising objections.

"Boys," said he, irrelevently. "Let's have a

smoke."

So they sat down on the logs, while every moment cried out

for its labor, and for ten minutes puffed tobacco into the air.

"Now," said John, knocking the ashes from his pipe,

"come on and let's get something done!"

They responded to a man. It was the consummate art of leadership.

John Walsh wore a hook in place of one hand, but he was a wonder

for all that. His resourcefulness, courage and unbending firmness

had much to do with winning the battle. He was there for one thing—to

drive piles in the right places—and nothing could turn him

from his purpose. If a man was not actually working, he had no

business on the No. 4 driver, even though he might happen to be

one of the owners. One intruder refusing to leave quickly enough,

John promptly knocked him overboard into the shallow water between

the driver and the bank. Then as the fellow did not rise, John

fished for him in the most matter of fact manner with his iron

hook, threw him on the bank, unconscious, and went on driving

piles!

Another time, the jam broke suddenly just as John had a pile

in the carrier ready to hammer into place. The driver was picked

up bodily and carried some distance. The crew were pretty well

frightened, but the instant the craft came to a standstill, Walsh

cut loose the hammer and drove that pile. He had placed it in

the carrier for the purpose, and he was going to finish the job

if he were carried to Jericho!

At this point

the men in charge originated one of those daring and original

plans which take their conception peculiarly in the American genius.

As the reader can see, the main difficulty lay in that the flood

was denied an outlet because of the logs jammed to its very bed.

Already, although the pressure was but slightly relieved by it,

the river had begun to spread laterally, thus carrying many of

the upper logs past the jam to the lake. The plan was to dig

a new channel for the river around the jam! Think of the magnificence

of the conception! At this point

the men in charge originated one of those daring and original

plans which take their conception peculiarly in the American genius.

As the reader can see, the main difficulty lay in that the flood

was denied an outlet because of the logs jammed to its very bed.

Already, although the pressure was but slightly relieved by it,

the river had begun to spread laterally, thus carrying many of

the upper logs past the jam to the lake. The plan was to dig

a new channel for the river around the jam! Think of the magnificence

of the conception!

A dredge was at once floated down from Grand Rapids. So swift

was the current that when the tug which accompanied and guided

the dredge, accidentally turned broadside to the channel for a

single instant, she was at once thrown so far on her beam ends

that the water poured into her main hatch. The dredge finally

got to work. In two days she had completed above the swing a new

channel some thirty-five feet wide. A great part of the river

immediately began to flow in this new bed; the pressure was relieved,

and so the danger point was passed for the moment.

Now ensued the breathing space, during which the Grand Rapids

logs hung at the iron bridge near that city. For some reason,

in spite of the local confidence above, Grand Haven never doubted

for a moment that the bridge would go eventually. Defenses were

strengthened. After a time, since nothing happened, it was resolved

to clear another channel through the jam.

To accomplish this men had to venture under the very breast

of it, to pry at the key logs until a portion of the face started,

and then in some manner to escape out of danger. While engaged

in this work, news arrived from Lowell and Plainfield, above Grand

Rapids, that the waters were again rising. It became necessary

at once to close the opening already made in order that the logs

might not break through it to the lake. To do so the driver had

to creep up into the very jaws of death. The tug captain refused

to tow the craft to her station.

"It isn't

safe!" he expostulated. "It isn't

safe!" he expostulated.

"You get right off this tug!" cried the owner. "Go

over to the middle of that ten-acre lot and lie down on your face!

See if you'll feel safe there! Here, Jim, you take this tug."

A long line was made fast to the stern of the driver and tied

to a tree out of danger around a down-stream bend. As the craft

crept up between and under the threatening timbers, men paid out

this line, so that always they retained connection with a point

of safety. In case of necessity they could let go forward, drop

down with the current past the bend, and swing themselves out

of peril with the stern line. The tug would have to escape as

best it could.

As has been stated, the piles were driven in bunches of sixteen,

bound together by chains. The clumps were further connected by

a system of boom logs and ropes to interpose a continuous barrier.

The driver placed and bound the clumps, the tug attended to the

rest.

Shortly before venturing on this hazardous undertaking, they

received word from Grand Rapids that the bridge had gone, and

that the logs were on their way down the river. At this the rivermen

gave up hope. Many of them ceased their exertions. The Government

driver, which had been placing five extra booms at intervals down

stream, unmoored and quit. The case appeared quite hopeless. If

Grand Rapids could not hold a hundred millions with iron defenses,

Grand Haven could certainly do nothing against them with wooden!

The mere impact would suffice to jar them loose.

"That settles

my fifty thousand dollar house!" said one lumberman. "Twenty

dollars a month is good enough for me now." "That settles

my fifty thousand dollar house!" said one lumberman. "Twenty

dollars a month is good enough for me now."

One firm alone refused to yield. They were the owners of driver

No. 4, the employers of John Walsh, and had retained the generalship

during the long battle. A last stand was offered.

"Boys," said the two members of this firm, "if

she starts to go, save yourselves the best way you can. Never

mind the driver, stay on top!"

And so the tug and the driver crept slowly up the boiling water

under the jam.

A pile was placed in the carriage, the hammer descended. At

once logs commenced to shoot out of the water end foremost all

around them. The pile had been driven into the foot of the jam,

so loosening timbers at the bottom of the river. Luckily none

of them hit either of the boats squarely, or the craft would have

been stoved in and sunk. The fault of position was remedied, and

the work begun.

Four times the jam quivered. Four times it paused again on

the brink of discharge.

"One more'll hold her!" said Walsh, anxiously.

The pile was placed. Without delay the heavy chains were thrown

around the winch, and the steam power began to draw the clump

together. On the other side of the little channel the tug lay

moored fore and aft. John Walsh stood on the boom coolly tying

the last cumbersome knot of the system of defense. Clark Deremo,

all alert, grasped the spokes of the wheel. In the engine room,

Norris, his hand on the throttle, stood ready to throw her wide

open at the signal. A man at either end watched the owner's upraised

hand, prepared to cut the mooring lines when it should descend.

"Look out, John," said the owner, quietly, "she's

getting ready."

The man addressed

folded the knot over without reply. The man addressed

folded the knot over without reply.

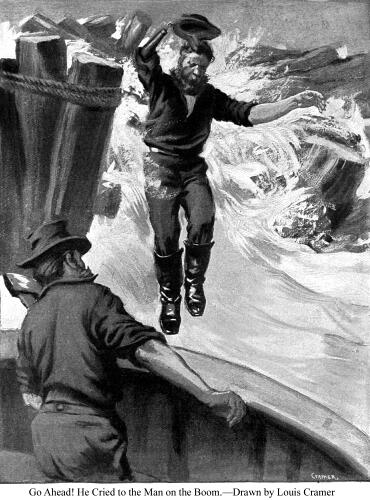

Up-stream the jam creaked, groaned, settled deliberately forward,

cutting a clump of piles like straw.

"She's coming!" warned the owner.

"Give me every second you can," replied Walsh, without

looking up.

He was just making the last turns.

The mass toppled slowly, fell into the swift current and leaped

with a roar. The man in the waist of the tug watched with cat-like

attention.

"Jump aboard!" he cried to the man on the boom, and

his raised hand descended at last.

With the motion the two axes severed the mooring lines, the

wheel whirled, the little craft shot from its leash like a hound.

And so fine had they cut it that the first logs smashed their

stern rail! But the opening was closed.

The driver had escaped around the bend, as planned. If either

craft had been fairly caught, it would have been overwhelmed.

Subsequently Walsh and his brave crew ventured in to strengthen

some neglected spots. They took the places on No. 3 driver of

a crew which absolutely refused to undertake such perilous work.

Thanks to the new river channel which had been excavated around

the head of the jam, the logs from Grand Rapids could be awaited

with some degree of confidence. The logs would simply be shunted

into the new opening and scattered over the broad marshes of Stearn's

Bayou. The hope seemed reasonable. But with the very first rush

came an iron bridge, which jammed square across the channel, effectually

blocking it.

This looked like the proverbial last straw. The bridge was

fearfully and wonderfully twisted. It took two days to remove

it, nut by nut, bolt by bolt, piece by piece. During that time

the old scenes had all to be relived. Men worked as though mad.

Excepting them, no one ventured on the river, for to be caught

meant to die. Old spars, refuse timbers of all sorts—anything

and everything was requisitioned that might help form an obstruction

above or below water. Sleep was forgotten. Food was brought directly

to the scene of work.

Other men were

equally busy hunting for piles. They took them where ever they

found them without attention to their owners. Farmer's trees were

cut out, and the farmers held at bay with peevies; pines belonging

to divers and protesting proprietors were felled and sharpened;

Holland and Muskegon furnished their quota by rail; even Uncle

Sam, the inviolable, was commandeered in a most cavalier fashion.

The D. & M. railroad company owned a fine lot of piles which,

with remarkable shortsightedness and lack of public spirit, they

refused to sell at any price. A crew of men took them by force.

Once, when other means failed, John Walsh was found up to his

waist in water, felling the trees of a wood, and dragging them

to the river by a cable attached to the winch of his driver. Other men were

equally busy hunting for piles. They took them where ever they

found them without attention to their owners. Farmer's trees were

cut out, and the farmers held at bay with peevies; pines belonging

to divers and protesting proprietors were felled and sharpened;

Holland and Muskegon furnished their quota by rail; even Uncle

Sam, the inviolable, was commandeered in a most cavalier fashion.

The D. & M. railroad company owned a fine lot of piles which,

with remarkable shortsightedness and lack of public spirit, they

refused to sell at any price. A crew of men took them by force.

Once, when other means failed, John Walsh was found up to his

waist in water, felling the trees of a wood, and dragging them

to the river by a cable attached to the winch of his driver.

And so, finally, for the second time, the auxiliary channel

was cleared. Gradually the pressure lightened. In three days more

the danger had passed. The impossible teas achieved.

All the rest of the summer was spent in the hardest kind of

work. The tangle had to be straightened; the logs which had been

carried inland a mile or more, to be restored to the river. All

must be sorted. Grand Rapids had to ship its cut back by railroad.

The Boom Company expended in all over sixty thousand dollars,

but it saved the community millions.

The men connected with this mighty crisis are to be found still

in western Michigan. The owners are wealthy business men; John

Walsh is considered the most reliable contractor in his town;

the seven members of No. 4's crew have risen to various posts

of responsibility afloat and ashore. And this again is characteristically

American. The fire that carried them through the weeks of the

"Big jam" was no momentary flicker; it has shone steadily

to guide them to success.

Logging Page

| Contents Page

|