|

|

|

|

A Seven Year Outing

By Frances Beecher Perkins

From the New England Magazine, 1900 |

|

|

Seven years may seem a long time for an

"outing," but truth is said to be stranger than fiction,

and this is a true story. The scene is laid in the southern part of

the Catskill Mountains, by the side of one of the loveliest and

clearest lakes with which that region abounds.

It came about in this way. A certain city

minister was invited by a neighbor to spend the summer vacation at

the Willeweemoc trout lake, which was owned and preserved by a club.

From there the minister strayed off into the forest primeval, and

found this exquisite sheet of water, which has ever since been known

by his name, and called the Beecher Lake. On his return to the city

he purchased a mile square of the wild land, which included the lake,

and the following spring took possession of it with his family,

determined to act as a self-appointed home missionary, untrammelled

by any necessity for filling pews and earning a salary. Here they

lived for seven years, with the exception of a few weeks in winter,

at first in tents, and then in a rough but comfortable cottage; and

here, the modern "babes in the wood" flourished with

unusual vigor.

|

|

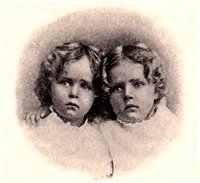

"Babes In The Woods" |

This name was fixed upon them by their aunt,

who had rare skill as a sculptor and modeller, and might have been a

second Harriet Hosmer. A low place near her tent abounded in a

light-colored clay that was easily worked, and one day she called the

party of campers to a lovely bower formed by the trees, and there,

side by side on the ground, displayed two little reclining figures

modelled in clay. They were so astonishingly like the twins that no

one could mistake the intention, and at the same time so brought to

mind the cruel uncle in the old story, even to the leafy covering by

the robins, that all exclaimed, "Behold, the babes in the

wood!" The real babes were enough alike to deceive their own

mother at a little distance, so that she could not tell one from

another, and would call either name. Sometimes the answer would be:

"Dat Margie, me May!" or again it was: "No May; me

Margie!" And when she attempted reproof, she would usually find

she was administering it to the wrong child. |

When the new road was cut through the woods,

some four miles to the lake, the last house was an old log one, and

the owner of it would entertain the party with stories of his

shooting wolves from his own door.

He thought city people were made of money, and

for a time obliged them to pay a dollar for a loaf of bread. The road

was at first only a wide path through the woods, meandering around

hills that were too high or too rough to go over, fording the shallow

streams, and crossing the deep ones on bridges of rough, unhewn logs.

Rocks abounded of every variety and thrown up at every possible

angle; but the good sure-footed horse made his way sagaciously over

or around them, drawing the longest and safest buckboard ever made.

This was a gift from friends in the Poughkeepsie church, and had been

made to order. The seat was the apex of a wide, low, pyramidal box,

in which the family supplies were carted to the lake, and it was a

never solved mystery how so many different articles could be stowed

away in it as appeared in the unpacking at the tent or cabin door. A

Saratoga trunk is as nothing in comparison. Unpicked chickens and

legs of mutton and bags of grain went often dangling from the back,

and in some cavity among them nestled the five-year-old elder

daughter, while the twins were tied upon the seat in front by their

mother's side, and the father walked ahead as guide and helper. Thus

began this remarkable outing. The first tent set up was on rising

ground, where a rivulet flowing from a very clear and cold spring

emptied into the lake. It was a large hospital tent with a fly

extending far over the sides, a good board floor with two long steps

in front like a piazza, the canvas opening at the back to admit the

heat from a sheltered stove on a cold or rainy day. Two or three

tents raised their snowy peaks in a group near by, forming a lovely

contrast with the deep green of the forest. The dining and cooking

room was a board shanty, with open side toward the lake; and never

was better food eaten, or more enjoyed than in this same shanty. No

servants were needed, as the campers all took part in this labor of

love. They were assisted, however, by the saucy little squirrels, who

picked up the crumbs at their very feet.

|

The Shanty |

The menu was, of course, not modelled on that

of Delmonico's; but who would have it in such a place? Variety is the

spice of life, and the appetite engendered by the mountain air

demands simple food. But the veriest gourmand could have asked no

better breakfast than was furnished by those delicate trout, only

half an hour from the pure water of the lake, half a pound in weight

and dotted with the most brilliant colors, which neither oven nor

frying pan could change. These trout, baked in cream and served with

the best of corn muffins and coffee, and discussed in the open air

with one of Nature's loveliest pictures in full view, might well

elevate the prosaic business of eating into a fine art. Necessity is

said to be the mother of invention, and an infinite variety of

appetizing dishes was evoked by thought and skill from very limited material. |

A cow was soon declared to be a necessary

adjunct to the menage, but then, "Who can milk her?" was

the question. It was at length settled that the minister should

perform that ceremony, he being the only one of the party with

sufficient knowledge in that line. Later on, when this first cow,

Daisy, had three companions, Buttercup, Dandelion and Wild Rose, a

butter-making establishment was set up, and one of the country lasses

placed in charge. The ice- cold spring was hollowed out, and jars of

milk and cream placed in its keeping. Then a roof was built over it,

and water power from the descending stream was applied to the dasher

of a churn. This was thought more humane and romantic than the usual

custom of putting a dog or sheep on to a treadmill. The babes of the

family, however, though they throve well on trout and buckwheat

cakes, had notions of their own about eating, as well as about many

other things, and as soon as the book with that title appeared,

fastened on themselves the sobriquet of "The Heavenly

Twins." Everything they could reach, from the surface of the

ground up, was put into their little mouths - berries, leaves,

stones, sticks, and even earth, indiscriminately. The woods seemed to

infect them with wildness. One day the mother returned home and found

all her bureau drawers locked. As she never used keys herself, she

was at a loss to understand this novel state of affairs. Exclaiming

in wonder, "What does this mean?" she was told by the

helpless father that he had done it to protect her treasures from

being eaten up or thrown away by the irrepressible twins.

|

|

|

It was not long before their neighbors from the

adjoining valleys and small farms, miles away, began to appear on the

scene; and the minister was asked to preach in the nearest

schoolhouse, which was about four miles distant. The following Sunday

they begged him to go to the next schoolhouse, eight miles away, --

and then to the one twelve miles distant; and thus began a series of

services which continued as regularly during the whole seven years as

if a $10,000 salary were the reward. It would be impossible to tell

the whole outcome of these gatherings; but the effect, as time went

on, became more and more apparent, even in external matters like

dress, food and housekeeping. Young men and maidens, old men and

children, babies, even, and whole families, came from far and near.

It would be difficult for outsiders to understand what a treat those

Sunday meetings were to people so isolated by distance from railroad

and town. It combined for them a picnic, a sociable, a theatre and

religious teaching. |

The family buckboard was, of course, driven

down into the valley every Sunday, and, while some rode, the others

trudged through the woods on foot. At first the babes and their

visitors wore shoes and stockings, after city fashion; but when they

saw all the other children in the freedom of bare feet, off came

their own footgear, and it was seldom resumed thereafter.

These Sunday services led, naturally, to a

desire for better singing, and singing schools, taught by this

minister of versatile talents, with organ and blackboard of his own,

were the result. This, again, led to the fact that, though the public

schools were in session for six months of the year, the so-called

teaching had been of such a character that neither children nor young

men could write or read writing, nor could they read a book aloud in

a comfortable manner. Whereupon the minister's wife rose up and

proclaimed: "I cannot stand this state of affairs in this

nineteenth century. I, myself, will apply for the post of public

school teacher in our district for the next three months' term, and

see if I cannot then get my business notes read by any boy in the

valley." So the family divided, a part boarding in the farmhouse

nearest to the school. This was in winter, and the four miles of

separation were easily travelled, for the snow lay always deep and

solid, and after being well packed by the teams and sleds, the

sleighing was something delightful.

When Christmas came the schoolhouse was the

centre of attraction. It was decorated as never before, with

evergreens of all kinds, and a Christmas tree loaded down with

strange fruits from the city delighted all hearts, young and old.

Shortly after came the closing examination day, and good letters to

parents were read aloud by those who, three months before, could not

form a letter. One young man of twenty-five learned to write a good

round hand in two weeks' time, and came in with the rest on the

letter question. City friends took much interest in this experiment,

and sent writing tablets and pretty desks and boxes of varying

construction, for rewards of merit. These are still treasured as most

precious, and can be seen in almost every house in the valley.

Lifelong friendships were formed between the pastor and his family

and the people, and generosity and good feeling flourished.

|

|

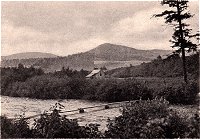

Beecher Lake |

The good roads and the lighter work of winter

encouraged visiting, and sufficient social life was enjoyed to keep

the people from stagnating. Large wood sleds, drawn by oxen and

loaded with the entire family, might often be seen going for an all

day's visit to some far-away neighbor; or a pair of horses and a

box-sleigh filled with straw and children; for the visitors were

always sure of a welcome. Hospitality flourished, as in all primitive

settlements. The jar of buckwheat batter was always ready for

visitors, and they were served at all hours of the day with thick,

white, fluffy griddle cakes and maple syrup, such as city folks know

nothing about. The talk was friendly and pleasant, as there was

little sickness to discuss or worries and jealousies and rivalries to

bring forward. Kindly feeling prevailed. Yet these people lived in

such houses that they often had to construct a spare room by a

festoon of bedquilts, and you would have said they were to be pitied

for their poverty. Not at all! "'Happiness, like heaven, does

not depend upon situation," nor on the abundance of things a man hath. |

But perhaps I am talking too much the lakeside

life; so out and bring forward the animals and show up our menagerie.

First and foremost were the friendly squirrels. You should have seen

the paterfamilias feed them with crumbs on his knee and shoulder, and

even on his head, for their and our entertainment. The twins, of

course, delighted in all the living things about them. They were

perfectly fearless and, like Kipling's Mowgli, were ready to

associate on equal terms with any animal that would allow them to do

so. A pair of tame chipmunks, with shaded stripes and bushy tails,

served them at one time as bedfellows and playmates. The end of that

intimacy was pathetic in the extreme; for the mother took one of the

chipmunks to Brooklyn to exhibit its attractions, and city life

proved too much for him, while his mate at home seemed to pine away

from the separation. Frogs and toads served also as playthings until

the summer aunt, who always occupied a tent, insisted that the deep

bass tones of the bullfrogs in their nightly concerts disturbed her,

and offered a reward of five cents for every pair of legs large

enough for a fricassee. So the pockets of the children were turned

into rattle-boxes filled with nickels, the aunt enjoyed her purchased

quiet, and the family its new French delicacy for the table.

The hunters of the party were first quite

successful with the deer, and all enjoyed stealthy glimpses of one

that came daily to drink at the lake. But to the ladies of the camp

it always seemed a pity that so beautiful a creature should be hunted

and slain for food, unnecessarily. Yet such are the contradictions of

the human mind that, when broiled venison did appear on the table,

sentiment seemed to disappear, and the pretty deer were forgotten.

The camp was not very far from the eastern

branch of the Delaware, and many a keen search for the tracks of bear

and deer, reported as being in the neighborhood, was conducted on

principles of Indian reasoning, and brought Cooper's "Deer

Slaver" and other stories so strongly to mind that the books had

to be brought out and read aloud, as had also "The Lady of the

Lake" and many another poem which gave expression to the romance

of this life.

The bears, being real wild beasts and large and

rare, made the deepest impression on the minds of these Outers. The

Outers owned a dog named Carlo, which was of very unusual size and

strength, and often carried the children on his back. One night, late

governess happened to be alone in the house, Carlo growled so

savagely that they ran to the window, and there saw a big brown bear,

clumsily walking around. Without a thought of fear, they at once

opened the door, and Carlo rushed out and chased his furriness up

into a distant tree, and continued barking for an hour or two, until

his master came home. Foolishly, he ran to greet his master, and let

the bear go free. Another fall, when blackberries were ripe and the

family went on a picnic to gather them on a neighboring mountain, it

reported that Mr. Bruin, who is a devoted lover of blackberries, been

seen only half a mile from the spot. But they only kept a little

nearer together than usual, and in sight of Carlo, and were on guard,

lest in picking berries they might pick the eyes of Mr. Bear. He had

the misfortune to get caught in a trap that very night, and the next

day the family were invited to feast on the most delicious meat they

had ever tasted, even the twins asking for a second helping. A bear

hunter in the neighborhood became a favorite visitor, and recounted

tales more interesting than any you can read. One bear he kept alive

for months, and built a log house for him; but after he had broken

bounds once or twice, he was deemed an unsafe neighbor. |

|

|

When the snow first came, the rabbit tracks

upon it made hunting the rabbits so easy that going after them was

like going to market in the city. They furnished many a savory stew,

roast and pie, in their season. The foxes, also, made themselves

known by their tracks on the snow. One was caught in his youth and

brought home for a pet, where big bright eyes, alert ears and sharp

nose made him most attractive; but nature at length grew stronger in

him than education, and away he went to his native woods.

Every one has heard of the porcupine of hot

countries, and doubtless owns one of his quills in the shape of a

penholder. One night his northern cousin visited this house in the

woods, and tried to get in at the back door. The noise he made with

his sharp teeth and claws was like the sawing of a carpenter. When

his summons was answered, he could not be found; and so he became a

nightly mystery, until a watch was set, and poor Carlo, in his

eagerness to help, thrust his nose into the quills of the hedgehog.

It took time and skill to get them out, as they are barbed like a fishhook. |

In the fall and early winter the table was

bountifully supplied with meats new as well a; old. A new kind was

the woodchuck, which was pronounced as good as pork. Flocks of wild

ducks and pigeons, on their way to the South, flew over the lake and

aroused a great commotion, while a large flock of domesticated ducks

furnished a novel sight to visitors, as they would all rise on the

wing and fly together over the lake at any time when called by the

three little girls, and land at their feet with the greatest

confidence. Roast goose could always be relied upon for festal days,

for geese were domesticated in the valley, and had furnished every

log house for years with the best of feather beds, which the winters

and open houses rendered most acceptable. But I think the pretty

mottled partridges were sought with the greatest eagerness, both as

furnishing the most highly prized delicacy for the table, and because

it was so exciting to come upon a bevy of them unexpectedly and to

hear the queer whirring sound as they rose from their covert and

showed the plump forms of the modest beauties.

The fishing, too, was always best in the fall.

Through the summer every possible contrivance was used to lure the

trout from their cool homes in the depths of the lake. One method was

to place on the lake a perfect fleet of toy boats, with bright little

flags to mark their positions. These had baited hooks and anchors

fastened to them, and were examined twice a day. Sometimes they

yielded a scant breakfast, and sometimes none at all. The neighboring

lakes then came to the rescue, with catfish and pike and perch, and

the streams near by with an inferior kind of trout, larger, yet of

imperfect flavor and color. A prettv sight it was when the first cool

autumn sunsets came, and the shining trout were leaping up out of the

water in every direction, as much as to say, "Catch me if you

can." Then the lady of the house blossomed out as a proud

provider. Taking her rod, fly and boat, and a companion to hold the

boat still in certain places, she secured in twenty minutes, without

money and without price, enough of the welcome shiners to furnish the

favorite breakfast of her family.

No season in the mountains was without its

peculiar pleasures. At the first suggestion of spring, though the

snow lay two feet -deep, the maple trees were selected, the auger

holes were bored, the spiles put in, and the pails put tinder to

catch the sap. Then the fireplace was built for boiling the sap, the

wood was laid the plans brought out, and the path from tree to tree

trampled down and made as smooth as possible for collecting the sap.

Then came the delights of sugar making, from the first boiling of the

clear liquid to the clarifying of the thick syrup and the

"sugaring off" into cakes. These cakes were large or small,

smooth, or moulded into any conceivable shape. By night and by day

the work went on in pleasant weather. Poor was the family which did

not succeed in securing enough sweets for the year.

Many a pleasant memory these three children

stored up. One spring, when the sugar camp was half a mile .from the

house and the twins were about six years old, they were allowed to go

alone to the camp, where their father and mother were at work, but

were warned not to step off the road to the right or left. One of

them "forgot," and, walking off the well beaten track, sank

down to her knees in the soft snow; and, try as she might, she could

not lift her little feet out of their prison -- her efforts only

sinking her deeper in the snow. Most children of that age would have

been frightened and cried; but no traces of fear ever appeared in

these mountainbred little folks. The other babe simply went on to the

sugar-making hut as fast as her feet could carry her, to tell

"papa," though you may be sure that that papa turned

somewhat pale and rushed to the rescue on the wings of love. Faster

yet he flew when he came into sight of the little face smiling at him

over the snow. Faith in papa had kept her safe from all harm, and the

snow shovel soon released her, to be carried the rest of the way in

his arms.

After the sugar making came the disappearance

of the snow and the search for wild flowers, of which more than

seventy-two different kinds grew near the house. Loveliest mosses

were gathered by large hands as well as little ones, and placed in

every dish that could be spared from the table or contrived from

boxes. On this foundation the blue-eyed hepaticas and forget-me-nots

were arranged; also the delicate pink and white anemone and the

deeply blushing spring beauty, while the scarlet fruit and white

blossoms of the partridge berry and the well known berries of the

wintergreen plant, on their pretty stems, might be seen in every

corner where a wide-mouthed bottle could be hung. In fact, Christmas

and Easter seemed to last the whole year round in this mountain

cabin; for, as summer came on and the wild flowers lessened in

number, the family induced many of the city florists' pets to come

and blossom for them in the wilderness. These found the leaf mould

and virgin soil much to their liking; and beds of pansies, petunias

and phlox reached a size and beauty seldom seen in ordinary life. One

year the pansy bed was near the road gate, and seemed to smile a

welcome to all visitors. It was usually the centre of a group of

children and grown-up folk, lying or sitting around it on the grass

and talking with or about the pretty little faces.

Nor was the kitchen garden neglected by these

dwellers in the upper regions. Their friend, E. P. Roe, of sainted

memory among the lovers of "small fruits" as well as sweet

stories, sent them a most welcome gift of more than three hundred

plants of his best strawberries. These were placed on a hillside

sloping toward the south, with the other fruits and vegetables. But

first the ground had to be prepared in the most laborious way. The

trees were cut down and turned into chief was just saying on one of

the company days, "We have all we want for the dinner except

fruit," when, lo! as she turned her eyes to the window she saw a

little procession of three middle-aged women coming up the winding

road, each with a pipe in her mouth, and the first with a big milkpan

on her head full of the lovely berries, all nicely hulled.

Next came the wild raspberry season, with its

canning and jellying; and it may be said of this fruit, also, that

what it gains in size by cultivation it loses in characteristic

flavor, firewood; and as they could not afford to wait for the stumps

and roots to decay, each one had to be treated with pickaxe and

shovel to the necessary depth, and then sawed or cut off and drawn

away by horses or oxen. Then the plough and the harrow were put to

work to finish the job. This had to be cut down, and the bees driven

away, before the man could take possession. |

|

Footbridge on the Delaware |

The lovers of strawberries were not dependent

upon these alone, however, for almost daily the small wild ones, of

truer and higher flavor and odor, were brought up from the valley.

They began to come as if in answer to a telephone call; for the

caterer-in- so that to taste these berries in their perfection they

must, be eaten, like the trout, in their native homes.

The honey hunts of summer must, in justice to

the busy bees, be also mentioned. A little brown bee, resting on some

flower, would be selected as guide, and his motions watched and

followed as quietly as possible. Sometimes he would seem to delight

in baffling his pursuers by doubling on his track or flying out of

sight and reach; but usually a skilled hunter was rewarded for hours

of patience by tracing him to his nest in some high tree. |

The clearing of some larger portions of land

for the farm was done in the fall, and differently from that for the

garden, and was so interesting as to draw the whole family daily to

the spot. Two men with sharp axes would attack one of the immense

trees, from opposite sides, about three feet from the ground. This

was not done in any haphazard way, but blow followed blow in the same

place, until the axes almost met in the middle of the tree; then one

last effort by a true adept in the art would lay the mighty monarch

low in the exact place desired. The sound of his fall is like no

other sound, and was always echoed and re-echoed by the surrounding

hills. The his limbs were torn from him one after another and piled

up in lengths o burn. The squirrels were much disturbed by these

performances, for often their surprising winter stores of beechnuts

were discovered and transferred to the keeping of the children.

It was one of the evening entertainments on a

frosty night to set fire to a dozen or so of these mighty piles,

thrusting poles into them to make the sparks fly upward, and watching

the reflections on the surrounding trees. You can imagine that warmth

and light were had in abundance on those occasions, and that many a

time the thought was expressed: "Oh, that we could send all this

wood to comfort families it so the poor who need much; it seems such

a waste of material to burn it just to get old trees, beautiful as

they were, not only in summer with refreshing shade and color and

whisperings, but in winter with the soft gray tracery of branches

against the sky, furnished a more wonderful sight in early autumn.

For a week or two after the first frost came, these mountain dwellers

were enveloped in a glory and beauty unknown elsewhere and which

would reward any one for hundreds of miles of travel. The lake was

surrounded by an amphitheatre of tree-covered hills, and these, from

the very edge of the lake to their summits, were one mass of richest

color. Their varying shades were so faithfully mirrored by the smooth

waters of the lake that you could not tell the reflection from the

tree itself, so that beneath, around and above them there were form

and color and glory indescribable. These days were softly lived, one

hardly knowing whether one were in heaven or on earth. |

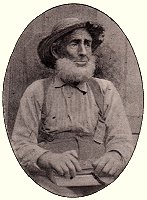

A Man Of The Valley |

In winter the trees at rare intervals gave you

a glimpse of fairyland. A storm of sleet at night, with Jack Frost on

hand to clothe, each tree and shrub and little twig with an icy coat

of mail, and then a brilliant sun to turn the whole into an amazing,

glittering spectacle, were the requirements for this show. The first

time this sight met the astonished gaze of the twins, they ran from

one window to another, clapping their hands and loudly exclaiming.

Every icy point was a rainbow; Aladdin's lamp was as nothing to that

magic morning. You would think there had been a shower of diamonds,

and that millions of them had come down to earth. A sleigh ride

followed the joy of the morning, and at every touch the overhanging

boughs sent down handfuls of crystals upon the laughing children. |

The Christmas of that year was memorable for

the number of boxes that were sent by city friends. Specimens of all

the toys on Twenty-third Street were unpacked in the family sitting

room, and the contrast between their city elegance and the

oldfashioned yawning cavern of a fireplace, with its rough backlogs

and foresticks, requiring the strength of two men to bring in and

arrange, was amusing. The winter evenings were, of course, generally

spent in this room, where the blazing fire made other light almost

unnecessary, and msic and reading, games and dancing, filled the

time. Yet sleighing and sledding parties were common, and the outdoor

life continued even in the coldest weather. Fires were built at the

edge of the lake on dark nights to light and warm the skaters, and

the ice first formed was so clear that the little ones drew up their

feet 'on the sled, seeing nothing between them and the water.

But the camp fire was the attraction on every

night in the year when it was possible to sit out of doors; and many

times when this seemed impossible on account of pouring rain, it was

built up and encircled by waterproofs and, perhaps, umbrellas. |

The Lake At Sunset |

The bright star Vega seemed always to have a

twinkling eye upon the' spot, and, therefore, Camp Vega became its

name. One of the pictures given shows an enduring style of sofa for

evening use, which was originated and made by a lady camper. Chairs

were constructed in a similar fashion, with barrel staves interwoven

with rope. If one wanted to be luxurious, one threw a red blanket

over one's wooden chair, and was then ready to sit still and be

entertained. First would come the sound of a distant owl; the

"Tu-whoo" would be repeated by the best imitator at the

fire; and then another and another of the wise-looking birds would be

heard, until the men and the birds were hardly distinguishable. When

an owl came near enough they all made a rush to 'catch him, though

they were seldom successful. |

They had many a so-called echo evening; for the

hills across the lake at that point sent back whatever sound was

given them in an ethereal, spiritual sort of fashion that was more

fascinating, and might have won for them a reputation equal to Echo

Lake, in the White Mountains. Much skill was shown in putting

questions in a form that would bring a desired answer. One was,

"Do I hate her, or love her?" Back came, "Love

her," with earnestness enough to convince the most sceptical.

Sometimes it seemed as if every supposed being in heathen mythology

must be stalking forth, so varied were the ghostly sounds. Squibs,

laughter, scoldings, angry words, were all sent forth and returned

with perfect exactness. The sweetest' echoes were of course produced

by musical instruments, and these were always on hand, especially the

bugle. The order was issued in Tennyson's words:

"Blow, bugle, blow! set the wild echoes flying."

One year a hollow tree some twenty-five feet

high was discovered with a few openings and thin places for windows.

This was carefully preserved until the night before the departure of

some summer friends, when it was placed on the camp fire with much

ceremony. The flames rushed and roared through it and out at the top

in fine style, and dancers circling round it with roundelay songs

made that evening one long to be remembered. Those who occupied the

seats round the fire can recall some sentimental and many ludicrous occurrences.

But the time came when the babes in the wood

and all their lakeside friends must leave their beloved retreat and

transfer themselves back to the city. The kindly influences of the

long outing had made the little ones all that children should be. If

it had not the same benign effect upon their elders, it was not the

fault of the outing.

Today, Beecher Lake is the home of the Dai Bosatsu Zendo-Kongo-ji, a Rinzai Zen Buddhist monastery.

Visit their web page

|

|