Artists' Excursion Over

the Baltimore & Ohio Rail Road

by Porte Crayon (David

Hunter Strother)

Harper's New Monthly Magazine—June, 1859

"Many

a noble heart,

"Many

a noble heart,

Many a regal head,

Labors for our native land

Harder than the horniest hand

For its daily bread;

Painter, poet, statesman, sage,

Toll for human kind,

Unrewarded but of Heaven

And the inner mind."—Anon.

THE ages of gold, of silver, of brass, and iron, as described

by the poets, are past. The present is the age of steam. By steam

the commerce of the world is carried on. By steam we travel over

sea and land. Steam has turned manufacturer, farmer, cook (although

it must be acknowledged it makes but a sorry business of this

last). Latterly, steam and the fine arts have scraped acquaintance.

The real and the ideal have smoked pipes together. The iron horse

and Pegasus have trotted side by side in double harness, puffing

in unison, like a well-trained pair. What will be the result of

this conjunction Heaven knows. We believe that it marks the commencement

of a new era in human progress; and it is meet, therefore, that

some record of the event should be given to the world.

On such an occasion, perhaps, the lions themselves should have

been the carvers; but it has pleased them to delegate the task.

Friends and fellow-excursionists! with the aid of your faithful

memories to supply its deficiencies, with your kindly good-humor

to interpret its freedom, with the light of your joy-giving spirits

to illuminate its dullness, we may indulge the hope that this

record will not be deemed altogether unworthy of the great event

it is designed to perpetuate.

Before entering upon our narrative we will indulge in a few

remarks upon the birth and ancestry of the principal actor in

our drama—Steam; and yet, in so doing, we are sadly puzzled

to know where to begin, or where to leave off. To what master-mind

does the world owe the great idea? Is it to Fulton? Both Fitch

and Ramsey used it before his day, and they got it from Oliver

Evans, and he doubtless from Watt; and Watt, through Savary, Papin,

and others, was beholden to the Marquis of Worcester. And is it

not proven that the Marquis obtained the secret in France, from

poor Solomon De Caus? who was imprisoned for trying to force the

idea into Richelieu's head against the will of the imperious Cardinal.

Then Italy claims the  honor

by Giovanni Bianca, and Spain, as the invention of Blasco de Garay.

But Hero of Alexandria, one hundred and twenty years before the

Christian era, speaks of a machine moved by the vapor of water,

in his work entitled "Spiritalia seu Pneumatica." Was it by this power that the obelisks were brought from their

quarries, and the monstrous sphinxes trundled about? May we not

suppose that the Chinese and Hindoos understood the subject long

ages before the sculptors of sphinxes and obelisks were born?

and that the first conceit entered Adam's head perhaps as he watched

the boiling of his wife's teakettle; for, to quote from a French

writer, "C'est que nos progres sont lents, plein de tatonnements

et d'incertitudes; qu'ils s'enchainent les uns aux autres, de

maniere a rendre bien problematiques toutes les questions d'origine

et de decouverte. Si Yon voulait faire une histoire complete de

la machine', it vapeur il faudrait remonter au commencement du

monde."

honor

by Giovanni Bianca, and Spain, as the invention of Blasco de Garay.

But Hero of Alexandria, one hundred and twenty years before the

Christian era, speaks of a machine moved by the vapor of water,

in his work entitled "Spiritalia seu Pneumatica." Was it by this power that the obelisks were brought from their

quarries, and the monstrous sphinxes trundled about? May we not

suppose that the Chinese and Hindoos understood the subject long

ages before the sculptors of sphinxes and obelisks were born?

and that the first conceit entered Adam's head perhaps as he watched

the boiling of his wife's teakettle; for, to quote from a French

writer, "C'est que nos progres sont lents, plein de tatonnements

et d'incertitudes; qu'ils s'enchainent les uns aux autres, de

maniere a rendre bien problematiques toutes les questions d'origine

et de decouverte. Si Yon voulait faire une histoire complete de

la machine', it vapeur il faudrait remonter au commencement du

monde."

Butler tells us that

"All the inventions which the world contains

Were not by reason first found out, nor brains,

But fell to those alone who chanced to light

Upon them by mistake or oversight."

This may be true in regard to a host of discoveries, and we

have read a great many anecdotes to the purpose; pleasant, if

not true. But the giant of the nineteenth century is not the child

of chance. Though its origin is lost in the mists of antiquity

for twenty centuries at least, it has been the nursling of labor

and genius. In assisting its development and progress, how "many

a noble heart," how "many a regal head, " has perished

unrewarded and unknown! But while rival nations may boast of priority

in conception, of having furnished a vague thought or inconclusive

experiment, the great result is directly and undoubtedly due to

the practical pertinacity of the Anglo-Saxon.

Next arises the question between the Anglo-Saxon of the Old

and the Anglo-Saxon of the New World.

Since the day that France awarded to Franklin the medal with

the famous legend, "Eripuit coelo fulmen sceptrumque tyrannis,"

the New World has generally led the Old in the great utilitarian

enterprises that mark the civilization of the age, and men have

begun to suspect that the true bird of wisdom is not the owl but

the eagle. Although Europe justly claims precedence in speculative

science, how many a grand principle has there lain dormant, inoperative

for centuries—a theme for the discussions of impractical

savants, a bauble for the entertainment of the curious—which,

when transplanted to the soil of the Great Republic, has quickly

developed into gigantic life and activity!

While to England

undoubtedly belongs the honor of having originated the railway,

yet the idea vegetated there for more than a century before it

fairly awoke to life and movement. And when at length the cautious

experiments, still unacknowledged and incomplete, made noise enough

to wake an echo in the West, the first response was the adoption

of the grandest and most audacious scheme for purposes of internal

commerce which has yet been conceived and executed, and in thirty

years thereafter our maps are streaked over with black lines representing

thirty thousand miles of railroad.

While to England

undoubtedly belongs the honor of having originated the railway,

yet the idea vegetated there for more than a century before it

fairly awoke to life and movement. And when at length the cautious

experiments, still unacknowledged and incomplete, made noise enough

to wake an echo in the West, the first response was the adoption

of the grandest and most audacious scheme for purposes of internal

commerce which has yet been conceived and executed, and in thirty

years thereafter our maps are streaked over with black lines representing

thirty thousand miles of railroad.

It was not until 1829 that the capability of the railway was

clearly and practically established by the introduction of steam

locomotives on the Liverpool and Manchester road, then in course

of construction. Fifty years before this event an ingenious American,

Oliver Evans, of Maryland, suggested the idea of railways for

purposes of general trade and travel, with steam-carriages as

the motive power. The Legislature of Pennsylvania treated his

application for a patent with contempt; and, wanting means himself,

his conceptions were not realized until half a century later.

To what extent his plans were matured and capable of being turned

to practical account may be inferred from the following prophecy,

extracted from a little volume published Anno Domini 1813:

"The time will come when people will

travel in stages moved by steam-engines from one city to another,

almost as fast as birds can fly, fifteen or twenty miles in an

hour.

"Passing through the air with such velocity, changing

the scenes in such rapid succession, will be the most exhilarating

exercise.

"A carriage will set out from Washington in the morning,

the passengers will breakfast at Baltimore, dine at Philadelphia,

and sup at New York the same day.

"To accomplish this, two sets of railways will be laid

(so nearly level as not in any place to deviate more than two

degrees from a horizontal line), made of wood or iron, or smooth

paths of broken stone or gravel with a rail to guide the carriages,

so that they may pass each other in different directions, and

travel by night as well as by day; and the passengers will sleep

in these stages as comfort. ably as they now do in steam stage

boats.

"Twenty miles per hour is about thirty-two feet per second,

and the resistance of the air will then be about one pound to

the square foot; but the body of the carriages will be shaped

like a swift swimming fish, to pass easily through the air. .

. .

"The United States will be the first nation to make this

discovery and to adopt the system, and her wealth and power will

rise to an unparalleled height."

In another paper, published in the Aurora of Philadelphia,

dated December 10, 1813, public attention is called to a project

for connecting that city with New York by railway, and, after

describing several plans for laying the proposed track, Mr. Evans

thus concludes: "I renew my proposition, viz.: as soon as

either of these plans shall be adopted, after having made the

necessary experiments to prove the principles, and having obtained

the necessary legislative protection and patronage, I am willing

to take of the stock five hundred dollars per mile, to the distance

of fifty or sixty miles, payable in steam-carriages or steam-engines,

invented by me for the purpose forty years ago, and will warrant

them to answer to the satisfaction of the stockholders, and even

to make the steam-stages run twelve or fifteen miles per hour,

or take back the engines at my own expense if required."

The confident zeal of the ingenious inventor seems to have

awakened no corresponding confidence in the public mind. When

we consider the character of the people whom he addressed, and

the stimulating necessity, in a country of vast extent and sparse

population, for extraordinary means of travel and transportation,

we can only account for the apathy with which his propositions

were received by supposing that the world was not then ready for

the subject. In those days were wars and rumors of wars, and,

amidst the thunders of battle and the downfall of kingdoms, "the

poor man's wisdom is despised, and his words are not heard."

Oliver Evans lived a generation too soon; and thus it was that

America lost the honor of originating, practically, the Railroad

system.

At length the temple of Janus was closed, and the time came for

the triumphs of peace.

As the husbandman

burns the rubbish from his field, and plows deep into the earth

that, among the clods and ashes, good seed may be sown to yield

its fruit in due season; so had the fields of Christendom been

wasted with fire, and broken up with the hot plowshare of war,

that, from the clods and ashes of ignorance and superstition,

a better seed might spring and nobler fruits be gathered.

As the husbandman

burns the rubbish from his field, and plows deep into the earth

that, among the clods and ashes, good seed may be sown to yield

its fruit in due season; so had the fields of Christendom been

wasted with fire, and broken up with the hot plowshare of war,

that, from the clods and ashes of ignorance and superstition,

a better seed might spring and nobler fruits be gathered.

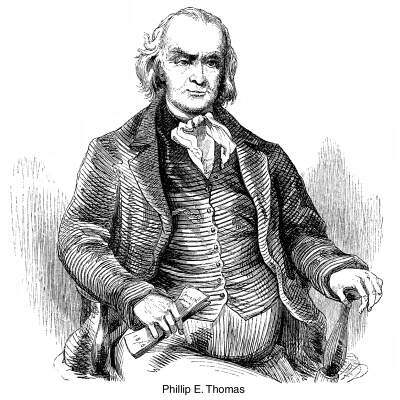

In the origination of such a work as the Baltimore and Ohio

Railroad, at a time when the system was still in its infancy,

we scarcely know which most to admire, the far-reaching sagacity

which conceived the idea, or the hardy and zealous faith in which

it was accepted. To Philip L. Thomas, Esq., a Quaker merchant

of Baltimore, is generally accorded the, honor of having been

the first to suggest and urge the undertaking, moved thereto by

some written advices from England. The city of Baltimore, at that

time worth but twenty-five millions, unhesitatingly embarked in

an enterprise to complete which has cost thirty-one millions.

We doubt whether there is on record a similar instance of commercial

pluck. Mr. Thomas still lives in the full enjoyment of the "mens

sana in corpore sano;" and, at the advanced age of eighty-four,

has the gratification, in his daily walks, of seeing around him

the magnificent results of his foresight. Verily, he that buildeth

is greater than he that destroyeth a city, and greater is his

reward. As the calm approval of the inner mind, the silent and

unsougnt homage of the thinking world, is nobler than the noise

of the fitful rabble that hails the last favorite of fortunate

war.

The work of construction was commenced on the Fourth of July,

1828, with appropriate pomp and ceremony. The venerable Charles

Carroll, of Carrollton, laid the first stone, and pronounced it,

next to his signing the Declaration of Independence, the most

important act of his life. During the progress of the work, from

year to year, old theories were exploded and new principles introduced,

increasing in boldness and originality as it advanced. "Its

annual reports went forth as text-books;" "its work-shops

were practical lecture-rooms;" and to have worthily graduated

in this school is an honorable passport to scientific service

in any part of the world. In its struggles with unparalleled difficulties—financial,

physical, legislative, and legal—the gallant little State

of Maryland found men equal to every emergency as it arose, and

the development of so much talent and high character in various

departments should not be esteemed the smallest benefit which

the country has derived from this great enterprise.

In the spring of 1858 a number of distinguished artists and

literati were invited to make a pleasure-excursion over the road

by a special train to start from Baltimore on the 1st of June.

The company's guests were to travel at their leisure, stopping

at all the prominent points of interest long enough to examine

the most notable productions of human science and labor; to enjoy

the magnificent natural scenery for which the line is so famous;

and, if so disposed, to exercise their talents after the manner

of Doctor Syntax—

To prose it here, to verse it there,

And picturesque it every where."

It was particularly appropriate that the pioneer of the American

railway system should also have been the first to inaugurate this

new and significant idea. For the first time in our history had

the great embodiment of utilitarianism extended the hand to the

votaries of the beautiful, claiming brotherhood and asking co-operation.

Our development, although without parallel in its rapidity, has

hitherto been confined too strictly to the hard, narrow path of

materialism. The elegant arts have existed among us rather as

potted exotics imported from abroad, baubles to amuse the idle,

luxuries to delight the rich, and, as such, awakening no real

sympathy in the hearts of the people. The artist walks among us

as a man apart, a solitary, a dreamer; misunderstood, unrecognized

in the great working hive of society. Bookman looks askance at

the ingenious handicraft: Hardfist despises the flaccid muscle

and velvet palm; timorous Respectability has a horror of superfluous

hair; venerable Conscientiousness is not sure but that the making

of graven images and likenesses of things on the earth is contrary

to Scripture.

But it can

not be that the brightest, busiest, and freest people on earth—a

people that has builded this vast temple to civilization in the

Western wilderness—will ever rest until the work is completed

and crowned by the ennobling hand of Art. Brethren, the day is

not far off. Like the cock's shrill clarion, heralding the coming

dawn, hearken to the invocation of the Iron horse:

But it can

not be that the brightest, busiest, and freest people on earth—a

people that has builded this vast temple to civilization in the

Western wilderness—will ever rest until the work is completed

and crowned by the ennobling hand of Art. Brethren, the day is

not far off. Like the cock's shrill clarion, heralding the coming

dawn, hearken to the invocation of the Iron horse:

"Come, ye gifted of the land—worshipers at the shrine

of the beautiful—from your seclusion in the clouds—come

down, and see the mighty works your kindred race has wrought;

cease from sighing o'er the mouldy Past; turn away from heroes

that are strangers to your people, from gods that are not theirs;

waste not your inspirations upon idle or unworthy theme; but come,

with hands of skill and hearts of fire, to glorify a Present worthy

of your powers. Scorn not the proffered friendship, but let the

artist clasp hands with the artisan; let the Poet walk with the

People. Illustrate, adorn, exalt, embellish, that the nobler aspirations

of the human soul after truth, beauty, and immortality may be

realized!

"Write, paint, sketch, and chisel that when ten, and thrice

ten, hundred years are gone, and our fires shall be quenched,

our iron bodies heaps of rust, the noble archways that have borne

us over rivers and mountain gorges shall have crumbled into ruin,

the stranger (perhaps a winged tourist from some other sphere),

finding a mossy stone carved with the letters B. & 0. R. R.,

may know that they stand for 'Baltimore and Ohio Railroad,' the

grandest and most renowned work of its age!"

The engineer

turned the steam-cock, and the invocation comes to a sudden stop.

But the light-hearted craftsmen had heard the call, and were not

backward sending in their acceptances—right glad to lay down

pencil and pallet for a season to join a whole-souled frolic;

to turn from the mimic creations on their canvas to scenes of

real life and sunshine.

The engineer

turned the steam-cock, and the invocation comes to a sudden stop.

But the light-hearted craftsmen had heard the call, and were not

backward sending in their acceptances—right glad to lay down

pencil and pallet for a season to join a whole-souled frolic;

to turn from the mimic creations on their canvas to scenes of

real life and sunshine.

So, on the afternoon of the 31st of May, the guests began to

assemble at the indicated place of rendezvous, the "Gilmore

House," in Baltimore; and then and there commenced the thousand-and-one

delightful little incidents which will live in many memories as

perennial fountains of refreshment. There were meetings and greetings

of old friends, school-mates, fellow-wanderers in foreign lands,

who had not seen each other for years; there were presentations

and salutations between those who, seen for the first time in

the flesh, had long been united in spirit; the appreciative recognition

of names well known to fame; the curious and admiring scrutiny,

to note in what manner of casket the Master had chosen to bestow

those rare gifts of which the world had spoken so approvingly.

But some of our best friends are missing our choicest spirits.

Where is N.? Where is R.? Left behind—too late for the train.

Bah! what a flattening sensation it produces to see the cars moving

off just as we arrive, red and panting, at the depot! How is  one overwhelmed with

self-abasement too deep for anger, the jest of grinning porters

and vulgar idlers; and, worse than all, to hear the mocking yell

of the fiendish locomotive in the rapidly lengthening distance!

But no regrets; our friends have sped a message that has put the

speed of the locomotive to scorn in its turn. They will join us

to-night. All's well!

one overwhelmed with

self-abasement too deep for anger, the jest of grinning porters

and vulgar idlers; and, worse than all, to hear the mocking yell

of the fiendish locomotive in the rapidly lengthening distance!

But no regrets; our friends have sped a message that has put the

speed of the locomotive to scorn in its turn. They will join us

to-night. All's well!

About eight o'clock in the evening the company sat down to

a dinner, especially prepared for the occasion. And such a dinner!

Ye gods! Talk of the suppers of Apicius, with their pencocks'

brains and other barbarous nonsense! We'll guarantee the luxurious

heathen never dreamed of such a feast as this. And if, as some

one observed, there was less wit current than might have been

expected from such a company on such an occasion, it may be fairly

inferred that the bountiful providence of our host of the "Gilmore"

met with an appreciation too deep for words. Besides, folks were

tired with the day's journey, and the transition from table to

bed was easy and natural.

Good-night! It still rains, but all the better. Things will

look fresher when it does clear up, and the waterfalls will be

in fine condition. The morning of the 1st of June dawned most

unpropitiously; the heavens were covered with damp, spongy clouds,

that squeezed out drenching showers whenever they happened to

jostle. But in spite of these unpromising appearances the excursionists

were at the Camden Street depot at the appointed hour. The missing

parties had arrived during the night, and, with the guests of

the previous evening, were "all agog to dash through thick

and thin."

But before we start we must describe the magnificent train

prepared for their accommodation. It was composed of six cars,

drawn by engine No. 232—a miracle of power, speed, and beauty,

and much such an animal as Job had in his eye when he described

Leviathan. The forward compartment of car No. 1 was fitted up

for the convenience of the photographers, and occupied by several

skillful and zealous amateurs of that wonderful and charming art.

Brother, give us your hand, though it be spotted with chemicals.

Is not the common love of the beautiful the true bond of union

between us? What matters it whether we see our divinity with eyes

of flesh or glass eyes?

Adjoining was the baggage and provision room, where heaps of

square willow baskets gave promise of good cheer. Next came the

dining-saloon, with a table running the whole length of the car;

then the parlor, furnished with springy sofas and a handsome piano-forte.

Following this were two cars with tables and desks for writing

and drawing, also containing comfortable sleeping apartments.

The last was the smoking-room, whose windows and rear platform

afforded the best opportunity for seeing the country.

A talented

and accomplished gentleman, Mr. William Prescott Smith, in charge

of the aesthetic and social department of the expedition, had,

on the part of the Railroad Company, welcomed and introduced the

guests to these elegant and luxurious quarters. Billy Hughes,

the Company's faithful and reliable "Passenger car Inspector,"

had, with penknife and hammer, examined the train from end to

end, and given official notice that all was right. 232, impatient

of delay, was stewing and fretting in his iron harness, when the

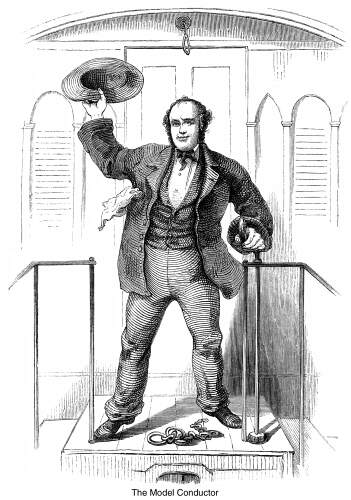

voice of Captain Rawlings, the model conductor, sung out, sharp

and clear,

A talented

and accomplished gentleman, Mr. William Prescott Smith, in charge

of the aesthetic and social department of the expedition, had,

on the part of the Railroad Company, welcomed and introduced the

guests to these elegant and luxurious quarters. Billy Hughes,

the Company's faithful and reliable "Passenger car Inspector,"

had, with penknife and hammer, examined the train from end to

end, and given official notice that all was right. 232, impatient

of delay, was stewing and fretting in his iron harness, when the

voice of Captain Rawlings, the model conductor, sung out, sharp

and clear,

"All aboard!"

The locomotive gave a yell of delight. Ding-dong! ding-dong!

we are off. Oh for the pen of Saxe, that we might express the

joyousness of rapid railway motion!

At starting our party numbered about fifty souls, collected

from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington,

besides several individuals from the country. All branches of

the liberal arts were handsomely represented, and we will wager

that it has never fallen to the lot of any other locomotive to

draw so rich a freight of varied talent and accomplishment.

But the weather? Still clouds and rain. No matter; it will

not dampen such a company as ours. Already two accomplished performers

have boarded the piano, and are storming away at the overture

of "Massaniello," with such concomitants as would have

astounded the fiery soul of the great Auber himself. Con moto—thirty

miles an hour—presto prestissimo! steam-whistle—sostenuto

e fortissimo! wheels—tremando e rinforzando! escape-pipe—staccato

e sfogato! Allegro—"Come o'er the moonlit sea"—forty

voices. Hurrah for music, wine, and good-fellowship! What care

we for clouds or rain?

In the mean time the train was rushing over the iron path at

a round rate. At the Washington Junction the pretty landscape

was completely befogged The picturesque valley of the Patapsco

to Ellicott's shrouded in mist. As they progressed the external

world of gray shadows was left to take care of itself, and the

tourists were richly remunerated by the opportunity thus afforded

of developing their internal resources. There was music, vocal

and instrumental; there was wit, Champagne, and deviled crabs;

there was humor, broad and jovial; conversation genial and intelligent.

From the numerous earnest and animated groups one may catch an

occasional characteristic word or thought amidst the din.

"Well,

old friend, how has the world gone with you since we last parted?

Do You remember the tour we made with D---- and M---- to Valombrosa

and Laverna? ……Those glorious evenings at our quarters

on the Lung Arno ...... And D---- is dead, poor fellow! There

perished a promising artist and a high-souled gentleman…..We

traveled together through Palestine and Egypt. I left him sketching

a Sphinx ...... Still in Rome, pursuing his art, poor, persevering

and enthusiastic…. And W----? Has a large family. I saw a

group of children by him in the last exhibition; well executed

and life-like...... he went to the East Indies...... the foliage

of Central America is rich beyond the power of a temperate imagination

to conceive...... doubtless, Greek art has fulfilled its mission

And Ruskin? Old gods overthrown, and new ones set up, which are,

worse…. it is singular how much attention a mere phrasemonger

can command, especially when he treats of subjects in which the

world is not deeply versed ...... peaks of the Andes, their bases

clothed in the wild luxuriance of tropical foliage, their summits

glittering with eternal snows."

"Well,

old friend, how has the world gone with you since we last parted?

Do You remember the tour we made with D---- and M---- to Valombrosa

and Laverna? ……Those glorious evenings at our quarters

on the Lung Arno ...... And D---- is dead, poor fellow! There

perished a promising artist and a high-souled gentleman…..We

traveled together through Palestine and Egypt. I left him sketching

a Sphinx ...... Still in Rome, pursuing his art, poor, persevering

and enthusiastic…. And W----? Has a large family. I saw a

group of children by him in the last exhibition; well executed

and life-like...... he went to the East Indies...... the foliage

of Central America is rich beyond the power of a temperate imagination

to conceive...... doubtless, Greek art has fulfilled its mission

And Ruskin? Old gods overthrown, and new ones set up, which are,

worse…. it is singular how much attention a mere phrasemonger

can command, especially when he treats of subjects in which the

world is not deeply versed ...... peaks of the Andes, their bases

clothed in the wild luxuriance of tropical foliage, their summits

glittering with eternal snows."

But enough of these scattered leaves. Could we have commanded

the services of Briareus as stenographer, what a volume of railway

talk we might have collected! Thus we passed the Frederick Junction

and the Point of Rocks—still cloudy. "We're getting

into the mountains, and every thing will be murky." Folks

begin to get discontented, and visions of a sunless world haunt

the imagination. But it is useless to murmur. "Jacques, open

another bottle."

As we approached

Harper's Ferry, suddenly a cry was raised on the foremost platform,

which was repeated from car to car until the whole train resounded

with the exultant shout, "The sun! the sun!" The dun

clouds, broken and flying, hastened from the field like a routed

army, while the conqueror appeared in all his might and majesty.

The heavens shone clear and blue as a baby's eye; the tender leafage

of the mountains looked fresh as budding girlhood; the swelling

bosom of the river flashed with its jeweled foam; the browsing

herds leaped and capered over the meadows in their uncouth gladness;

men rejoiced in the light with a sentiment akin to worship. It

seemed as if all nature was breaking forth into song. "Gaudeamus!" Even the stout engineer, wiping the smoke from his eyes with

his grimy hand, cried out, "Go it, old fel'! 'pears as if

he was hung out a purpose!"

As we approached

Harper's Ferry, suddenly a cry was raised on the foremost platform,

which was repeated from car to car until the whole train resounded

with the exultant shout, "The sun! the sun!" The dun

clouds, broken and flying, hastened from the field like a routed

army, while the conqueror appeared in all his might and majesty.

The heavens shone clear and blue as a baby's eye; the tender leafage

of the mountains looked fresh as budding girlhood; the swelling

bosom of the river flashed with its jeweled foam; the browsing

herds leaped and capered over the meadows in their uncouth gladness;

men rejoiced in the light with a sentiment akin to worship. It

seemed as if all nature was breaking forth into song. "Gaudeamus!" Even the stout engineer, wiping the smoke from his eyes with

his grimy hand, cried out, "Go it, old fel'! 'pears as if

he was hung out a purpose!"

Over that imposing covered bridge, spanning the Potomac River,

we pass from Maryland into Virginia. Through that stupendous gateway,

walled with precipitous rocks, we enter the great valley.

At Harper's Ferry the excursionists were informed that they

would have four hours at their disposal; and thereupon, with commendable

alacrity, they set about the business of sight-seeing, each taking

the road that chance or preference suggested. Some climbed the

steep and winding path that led to Jefferson's Rock—a point

of view made famous by the pen of the sage of Monticello; some

visited the work-shops of the National Armory, where our weapons

of war and glory are manufactured by thousands and hundreds of

thousands; some strolled quietly along the river's brink, preferring

the contemplation of scenes less extended but more picturesque

than those visible from the hill-tops. For our part-having been

familiar with this romantic spot from boyhood—we went to

sleep.

Harper's Ferry

is situated on a point of land at the confluence of the Potomac

and Shenandoah rivers, and opposite the gap in the Blue Ridge

through which the united streams pass onward to the sea. The fact

that it is the seat of a national armory, and has been described

in glowing language by Jefferson, may have given it a wider notoriety

than the comparative merits of its scenery would justify; and

the tourist who only gives it a passing glance may experience

a feeling of disappointment. But if, instead of four hours, he

should be fortunate enough to have four days at his disposal,

or even four weeks, to pass in exploring the town and its environs,

he can be no true lover of the sublime, romantic, and beautiful,

if he fails to acknowledge that his time has been well spent,

and that Harper's Ferry has justified her ancient renown.

Harper's Ferry

is situated on a point of land at the confluence of the Potomac

and Shenandoah rivers, and opposite the gap in the Blue Ridge

through which the united streams pass onward to the sea. The fact

that it is the seat of a national armory, and has been described

in glowing language by Jefferson, may have given it a wider notoriety

than the comparative merits of its scenery would justify; and

the tourist who only gives it a passing glance may experience

a feeling of disappointment. But if, instead of four hours, he

should be fortunate enough to have four days at his disposal,

or even four weeks, to pass in exploring the town and its environs,

he can be no true lover of the sublime, romantic, and beautiful,

if he fails to acknowledge that his time has been well spent,

and that Harper's Ferry has justified her ancient renown.

A capital dinner at Entler's solaced the excursionists after

their scrambling rambles, and at the appointed hour they again

took their seats in the train. As they were about starting their

attention was directed to the figure of a man, half-sculptured

half-painted by the plastic hand of Nature on the face of an impending

cliff. This is supposed by the vulgar to bear a marvelous resemblance

to Washington; and without meaning to pay the picture a pointed

compliment, we must admit that it counterfeits the physical traits

of the first President quite as well as many of his successors

in office have represented his moral virtues.

Continuing our route westward through portions of the fertile

counties of Jefferson and Berkeley, we arrived about five o'clock

in the afternoon at Martinsburg, one hundred miles from our starting-point.

At this station the Railroad Company have extensive work-shops

and stabling for their iron animals, which are duly groomed and

doctored, and make night and day hideous with their noise-reminding

one of Paddy's description of the World's Fair:

"There's staym ingynes,

That stand in lines,

Enormous and amazing;

That squeal and snort,

Like whales in sport,

Or elephants a-grazing."

The clear weather had become a fixed fact, with every promise

of continuance. The world was to be no longer without a sun—the

excursion no longer to miss the smiles of beauty. The Valley of

Virginia owes little of her goodliness and glory to the hand of

man. Her swelling hills are crowned by no stately edifices; no

fair cities lift their embattled towers above her rich-leafed

forests, nor gilded domes reflect the golden radiance of her sunsets;

no ivy-mantled ruin woos the tourist from his path, steeping his

soul in the regal sadness of ancient memories. Yet the valley

boasts of gifts choicer and fairer than these, "of that brave

wealth for heart and eye."

"Fresh from the hand of the All-giver,

Mountain, wood, and sparkling river,

Fatling herds and fruitful field,

All joys that peace and plenty yield,

And more, oh, pleasant land! is thine

Thrice bless'd by bounteous Power Divine.

Earth's sweetest flowers here shed perfume,

And here earth's fairest maidens bloom."

And lest the

passing traveler should unwiltingly look in seem upon the old

town of Martinsburg because, forsooth, the genius of architecture

smiled not on her humble birth, let him know that she may rightfully

claim a share in the foregoing poetic commendations, and that

he fame of her hospitable homes and lovely daughters is wide-spread

and well merited.

And lest the

passing traveler should unwiltingly look in seem upon the old

town of Martinsburg because, forsooth, the genius of architecture

smiled not on her humble birth, let him know that she may rightfully

claim a share in the foregoing poetic commendations, and that

he fame of her hospitable homes and lovely daughters is wide-spread

and well merited.

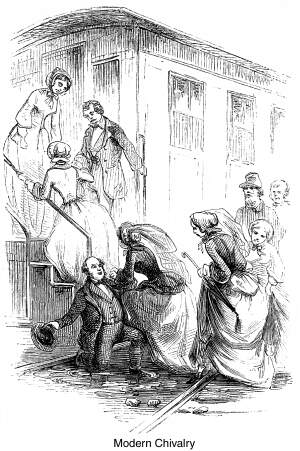

Now it had been arranged that several ladies should join the

excursion at this place, and when the train stopped in front of

the Depot Hotel quite a bevy appeared on the platform. As they

approached the steps of the parlor car their progress was arrested

by a black puddle left by the recent rains.

"Let me run for a chair," said one gallant escort.

"Get a dry board," suggested another.

Gentle Sirs, you are slow: this is no time nor place for laggard

courtesy. Quick as thought Captain Rawlings stepped forward, and

gracefully dropping on one knee in the water, made a stepping-place

of the other, firm and steady as an arch of limestone. With smiling

acknowledgments the fair Martinsburgers skipped over, and reached

the car with unsoiled slippers.

Poets have sung, artists have painted, historians have recorded

the gallantry of Raleigh, who threw his cloak in the mud to save

the shoes of Queen Bess. Is the flattery accorded to the vanity

of a royal virago a nobler theme than the instinctive homage of

manhood to innocence and beauty? Shall the muses laud the venal

fawning of the courtier, and the unbought chivalry of the man

of the people be forgotten? No! for cheers greeted the gallant

Captain as he rose, and there was, besides, an appreciative eye

that marked the deed—a skillful hand that fixed the scene

and decreed it immortality.

The train arrived

at Sir John's Run about seven o'clock, and the excursionists here

found coaches waiting to convey them to the Berkeley Springs.

As daylight was waning rapidly they lost no time in bestowing

themselves in or about these omnivorous vehicles, calculated for

nine passengers each, but carrying five-and-twenty if necessary.

Forty odd souls and bodies, with their baggage, were packed in

three carriages; and the party, under the guidance of Jimmy Jack,

the most-renowned whip in Virginia, started up the romantic gorge

of Sir John's. As the roads had had the benefit of two months'

steady rain, the travelers had a good opportunity of realizing,

for two miles and a half, what their ancestors would have considered

very comfortable staging. Yet such is the degeneracy of the age

that some grumbled, and swore it was the d----t route they had

ever passed over. It was quite dark when the coaches drove up

in front of the hotel, and discharged their cargoes of excursionists,

filled with enthusiasm, and quite ready for supper. Nor was it

long before a substantial meal had taken the place of the enthusiasm,

and the company assembled in the big dining-room to see what further

entertainment might be drawn from the social talents of the party.

The train arrived

at Sir John's Run about seven o'clock, and the excursionists here

found coaches waiting to convey them to the Berkeley Springs.

As daylight was waning rapidly they lost no time in bestowing

themselves in or about these omnivorous vehicles, calculated for

nine passengers each, but carrying five-and-twenty if necessary.

Forty odd souls and bodies, with their baggage, were packed in

three carriages; and the party, under the guidance of Jimmy Jack,

the most-renowned whip in Virginia, started up the romantic gorge

of Sir John's. As the roads had had the benefit of two months'

steady rain, the travelers had a good opportunity of realizing,

for two miles and a half, what their ancestors would have considered

very comfortable staging. Yet such is the degeneracy of the age

that some grumbled, and swore it was the d----t route they had

ever passed over. It was quite dark when the coaches drove up

in front of the hotel, and discharged their cargoes of excursionists,

filled with enthusiasm, and quite ready for supper. Nor was it

long before a substantial meal had taken the place of the enthusiasm,

and the company assembled in the big dining-room to see what further

entertainment might be drawn from the social talents of the party.

Socrates,

having wearied himself with a long lecture on the difference between

the exoteric and esoteric doctrines of philosophy, and feeling

the need of recreation, joined some boys who were playing at leap-frog

in the academy yard. As they played, numbers of the academicians

passed to and fro; but the presence of these wise and venerable

men did not in the least interfere with the game. Presently there

was seen approaching a highly respectable Athenian"—one

of a class that mistakes pomposity for dignity, gravity for wisdom.

"Boys, we must stop this," said the sage, hastily resuming

his rptg6vtov; "there's a fool coming!" So the

door of the great hall at Berkeley was closed, to shut out the

fools, while the cloak of ceremony was laid aside and the evening

devoted to

Socrates,

having wearied himself with a long lecture on the difference between

the exoteric and esoteric doctrines of philosophy, and feeling

the need of recreation, joined some boys who were playing at leap-frog

in the academy yard. As they played, numbers of the academicians

passed to and fro; but the presence of these wise and venerable

men did not in the least interfere with the game. Presently there

was seen approaching a highly respectable Athenian"—one

of a class that mistakes pomposity for dignity, gravity for wisdom.

"Boys, we must stop this," said the sage, hastily resuming

his rptg6vtov; "there's a fool coming!" So the

door of the great hall at Berkeley was closed, to shut out the

fools, while the cloak of ceremony was laid aside and the evening

devoted to

"Sport that wrinkled Care derides,

And Laughter holding both his sides."

If the wit that sparkles is often too subtle for the power

of pen or pencil, the kindly humor that warms is more picturesque.

This evenings entertainment furnished abundance of both. There

were songs—humorous, sentimental, tragic, characteristic,

and descriptive. The softer sorrows of that mournful ditty, the

"Bold Privateer," were followed by the noisier vexations

of' the man who "bought tripe on Friday." The Wordsworthian

sonnet of "One Fish-ball" was contrasted with the gin-shop

tragedy of "Sam 'All," that made the listeners' hair

stand on end. Then the learned elephant was introduced, who went

through his astonishing performances with a degree of intelligence

almost human. There were mysterious tricks of legerdemain; and,

to conclude, a gentleman drew a carving knife out of his mouth,

supposed to have been accidentally swallowed at supper. The negro

waiters were so awe-struck by this last feat that they were afraid

to touch the knife for some time afterward; and, when the party

left next morning, carefully counted over the spoons, frilly impressed

with the belief that Satan was traveling with the excursionists.

Whether it

was owing to the sedative qualities of the waters of Berkeley

or other causes, the travelers enjoyed a night of profound repose.

Betimes in the morning they were stirring about the village and

public grounds—some sight-seeing, some enjoying a souse in

the glorious pools for which this place is celebrated. Many great

names, now historic, are associated with the fountains of Berkeley,

so that there we trod on classic ground. But these reminiscences

are too numerous and interesting to be treated in an episode.

Of its present attractions we may only say, "The proof of

the pudding is in the eating thereof."

Whether it

was owing to the sedative qualities of the waters of Berkeley

or other causes, the travelers enjoyed a night of profound repose.

Betimes in the morning they were stirring about the village and

public grounds—some sight-seeing, some enjoying a souse in

the glorious pools for which this place is celebrated. Many great

names, now historic, are associated with the fountains of Berkeley,

so that there we trod on classic ground. But these reminiscences

are too numerous and interesting to be treated in an episode.

Of its present attractions we may only say, "The proof of

the pudding is in the eating thereof."

After a hearty, old-fashioned breakfast the excursion exchanged

compliments with its host and parted with three cheers and a tiger.

As the morning was pleasant many preferred to cross the mountain

on foot, and the coaches, with lighter loads, rejoined the train

in good time.

Westward ho! with exhilarating speed, diving deeper and deeper

into the mountains. At one time sweeping and circling with the

graceful sinuosities of the river, at another darting straight

through a projecting spur; now under the cool shadow of a beetling

cliff, then gayly emerging into sunshine and open fields. The

steady fire of appreciative comments showed that the artistic

sense was thoroughly aroused.

"Exquisite!"

exclaimed one. "This is a perfect Claude!"

"Exquisite!"

exclaimed one. "This is a perfect Claude!"

The ladies looked earnestly at a patch of plowed ground—

"What tinting! Ah, do observe those rocks; how delicately

tender!"

"As a lover's heart," whispered an arch fair one.

"It has precisely the tone of a Ruysdale.

"The tone is any thing but agreeable," said another,

as the steam-whistle closed an agonized yell.

"What noble breadth in the landscape to the right!"

"Yes; it is a mile wide, at least-you mean the meadow?"

"Per Bacco! What an object for a foreground! That

blasted tree reminds me of Salvator."

"It has a frightened look," quoth she. Ill prefer

them with leaves."

"Then what magnificent depth of shadow in the gorge before

us!"

"Pray Heaven we may not tumble in!"

But what do the uninitiated know of the technical ecstasies

of high art; of the contour of Angelo, the feeling of Raphael,

the coloring of Titian, the corregisticy of Corregio? We will

even let them pass.

At New Creek we laid by for the Western passenger train, which,

in passing, left a brilliant addition to the artistic and literary

material of the excursion in the persons of several guests from

Cincinnati. A little after mid-day we arrived at Cumberland; and

after part-taking of an excellent dinner at the "Revere House"

the company separated, to seek in various directions such objects

of curiosity and amusement as the town and its vicinity afforded.

The town of Cumberland is situated in a romantic basin, surrounded

by lofty and picturesque mountains. It has been more fortunate

than most of our American towns in its architectural embellishments,

which seem to have been designed for their places, and, instead

of marring, add to the effect of the surrounding scenery. Considering

its position and circumstances, the Gothic chapel is one of the

prettiest bits of architecture in the country.

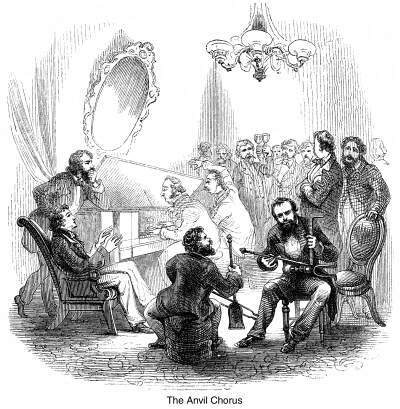

A gorgeous sunset closed the second day, and gave promise of

a bright to-morrow. Those who had been wandering in the hills,

or had made episodical excursions to Frostburg and Mount Savage,

returned well pleased with what they had seen, and the  company reassembled in force in the parlors

of the hotel. Here some of the amusements of Berkeley were repeated;

and with the, assistance of a fine piano and some other instruments

happily improvised for the occasion, the anvil chorus from "

Il Trovatore" was performed with stunning effect.

company reassembled in force in the parlors

of the hotel. Here some of the amusements of Berkeley were repeated;

and with the, assistance of a fine piano and some other instruments

happily improvised for the occasion, the anvil chorus from "

Il Trovatore" was performed with stunning effect.

On the morning of the third day it rained, and damp masses

of cloud hung about the sides and obscured the summits of the

mountains. The artists, however, found more to admire than regret

in this circumstance. What could be more appropriately brought

together than clouds and mountains? Each lent and borrowed grandeur

from the other.

The company breakfasted on board the train at full speed. During

the meal a furious thunderstorm burst over the moving hostelrie.

It was magnificent, and we laid down our knife and fork to quote

Byron:

"The sky is changed, and such a change! O night,

And storm, and darkness, ye are wondrous strong!

Yet beautiful in your strength as is the light

Of a dark eye in woman—"

"Please pass beef-steak for the lady."

"Certainly."

"Far along,

From peak to peak, the rattling crags among,

Leaps the live thunder—not from one lone cloud,

Put every mountain now hath found a tongue;

And Jura answers from her misty shroud

Back to the joyous Alps that call to her aloud."

"Will you have a deviled crab?"

"Thank you, yes, Byron and deviled crabs go very well

together."

"Oh! I have loved—"

"What-crabs?"

"No, my, friend—the ocean."

"Why, in the name of sense, don't you eat your breakfast?".

"Ah, what a pity they should have happened together! A

thunder-storm, which I adore; and breakfast, which is essential.

I can get no good of either.

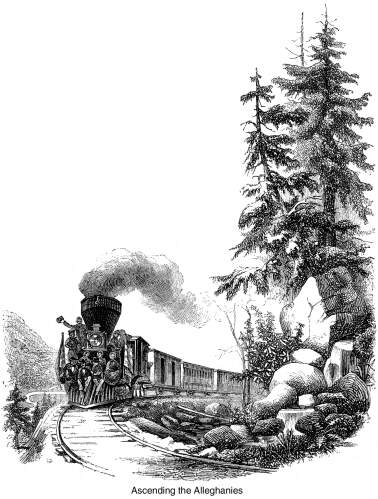

At Piedmont,

208 miles from Baltimore located the central machine shops of

the road; around which has grown up a town of twelve hundred inhabitants.

As its name indicates, it lies at the foot of the main chain of

the Alleghanies—the great back-bone dividing the waters of

the East from the West.

At Piedmont,

208 miles from Baltimore located the central machine shops of

the road; around which has grown up a town of twelve hundred inhabitants.

As its name indicates, it lies at the foot of the main chain of

the Alleghanies—the great back-bone dividing the waters of

the East from the West.

Up to this point the course of the Baltimore and Ohio Road

has led us through a country rugged and difficult indeed, but

sufficiently practicable upon the ordinary principles of railroad

engineering received and in use elsewhere. We have remarked the

elegant design and durable materials of its numerous tunnels,

crossways, and bridges, and the general substantial and permanent

character of its construction; but as yet it has exhibited none

of the peculiar features entitling it to that marked pre-eminence

which is claimed for it over all similar works in the world. It

is in the passage from Piedmont to Grafton that these bold and

original characteristics are fully developed. On this division

grades have been adopted averaging 116 feet to the mile—at

one place for eleven consecutive miles, eight miles at another,

and on either side of the Kingwood Tunnel, for some distance,

are grades 106 feet to the mile.

This system, when first proposed by the Chief Engineer, B.

H. Latrobe, was so far in advance of any thing which had been

yet attempted, and so contrary to received theories, that the

Company became alarmed, and a popular outcry was raised against

it. Fortunately for the enterprise, and for science itself, the

genius which conceived the idea was united with the courage to

sustain it. The result has been a splendid success. Thus, by one

bold leap, the Alleghanies were scaled, and the Mountains of Difficulty

which existed in the imaginations of the scientific world were

dissipated.

As the train commenced ascending the mountain a number of the

excursionists, including the ladies, took their seats on the front

of the engine and cow-catcher, for the purpose of obtaining a

better view of the grand scenes which were opening before and

around them. Such was the confidence felt in the steadiness and

docility of the mighty steed that the gentlemen considered it

a privilege to got a place; while their gentler companions reclined

upon his iron shoulders and patted his brazen ribs as though he

were a pet pony.

In the tales of chivalry, when a knight has rescued a beauteous

damsel from some impending danger, or is engaged in the equally

praise worthy business of stealing her away from her father, his

war-horse is represented as being highly flattered with the honor

of bearing the precious burden, and as manifesting his sense of

it with arching neck and kindling eye, etc. As might and magnanimity

are supposed to be inseparable, we may doubtless imagine that

"232" appreciated his position; that he humped himself

with pride, moderated his whistle, and "roared as gently

as a sucking dove;" tripped it mincingly up the savage steep-smoothly

as though his joints were greased with perfumed oil. Doubtless

he did all these things and more; but we were occupied with the

grandeur of the mountains; the awful gorge, deepening as we progressed,

through which the savage river toiled and raged; the mossy rocks

and groups of lofty firs near at hand, that gave the scene a Norwegian

aspect; the silvery streamlets flashing through sombre thickets

of evergreen; the gorgeous bouquets of azalia and mountain honey-suckle,

that recalled the luxuriance of the tropics.

At Altamont we had attained the summit of the Alleghany, and

the highest point on the route, 2638 feet above the ocean-tides.

It is a well-established fact that as persons ascend to considerable

heights there is a corresponding elevation of the spirits, an

expansion of the faculties—whether referable to the condition

of the atmosphere or innate causes we can not decide, but will

relate a remarkable incident bearing on the subject.

A gentleman, happening to overhear one of the ladies express

her admiration of the flowers that bloomed in wild profusion on

the summit plains, gallantly descended into the thickets, and

gathering a bouquet of the most perfect specimens, carefully inclosed

it in a chalice of graceful ferns. Returning to the car, he presented

it with the following address:

"Madam, the greatest English poet sings how

"'Proserpina gathering flowers,

Herself, a fairer flower, by gloomy Dio was gathered.'

On which occasion, Madam, the lovely daughter of Ceres was

like the flowers I have the honor of presenting to you—a

bouquet in-fern-al."

Whether this

is to be classed among the meteorological or psychological phenomena

is an undetermined question; but immediately thereafter the train

began to descend by a gentle slope into the region of the glades—those

breezy highland meadows lying between Altamont and Cranberry Summit.

Whether this

is to be classed among the meteorological or psychological phenomena

is an undetermined question; but immediately thereafter the train

began to descend by a gentle slope into the region of the glades—those

breezy highland meadows lying between Altamont and Cranberry Summit.

A short call at the "Oakland Mountain House," then

a rapid run over Cranberry Summit, and down the mountain for twelve

miles, by grades similar to those by which we ascended, brought

us to the famous Cheat River, whose amber waters roll through

mountain gorges two thousand feet in depth. We have tried our

pen on less imposing scenes, but here we are dumb. Possibly we

started on too high a key in the outset, like the enthusiastic

Frenchman with his "grande! superbe! magnifique!" and, having exhausted our superlatives, have no resource but to

shrug our shoulders and say, Ah, very pretty!"

The Cheat River region is the great scenic lion of the road,

as the Tray Run Viaduct is the mechanical wonder. At this last-mentioned

point the train laid by for several hours to give the artists,

poets, and photographers an opportunity to exercise their faculties.

The road here is located along the steep mountain-side, about

three hundred feet above the bed of the river. Over a ravine making

down at right angles with the main gorge the viaduct in question

is constructed, carrying the track 225 feet above its base. The

structure is as admirable for its light and graceful form as for

its evident strength and the imperishable durability of its material.

From the high embankment that overlooks the river one may see

the line of the road for some distance up and down; and nowhere

else, perhaps, does the result of human labor lose so little in

the immediate comparison with the grander works of nature. One

wonders alternately at the vastness of the obstacles and the completeness

of the achievement in surmounting them.

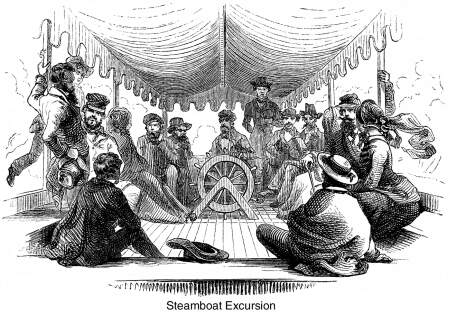

Resuming our westward course, with a number of ups and downs,

over rivers and under mountains, passing the Kingwood Tunnel,

four thousand one hundred feet in length, we arrived at Grafton

a little before sunset. Immediately on landing, a small party

of the excursionists, a dozen or fifteen in number, composed of

the ladies and their immediate attendants, embarked on a miniature

steamer for an episodical pleasure trip on the Tygart's Valley

River. The boat, which was about thirty feet long, and had a boiler

like the hotel teakettle, puffed along in a way that reminded

one of the early efforts of a young whale. But as speed was no

object, the little animal's fussy endeavors only served to entertain

the company. There was something dramatic in the contrast between

these scenes and those they had just left. From the rushing and

roaring of the cars through lonely and. savage mountains they

suddenly find themselves gliding with swan-like motion on a river

calm and beautiful as an Italian lake. Reclined beneath the picturesque

awning that covered the after-part of their little vessel, they

luxuriated in the evening coolness of the summer air, and looked

with delight upon the placid bosom of the stream, that mirrored

the rich overhanging foliage of the beech and maple, and mimicked

with exquisite art the hues of sunset, as they changed from purple

and flaming gold tothe soft violet of twilight. At intervals several

well-trained voices discoursed harmonious music in accordance

with the spirit of the scene, that nothing might be wanting to

complete the enchantment of the fairy voyage.

Three consecutive

days of activity and excitement had fatigued even the elephant;

and after a short but brilliant musical entertainment in their

own parlor, the excursionists went to bed.

Three consecutive

days of activity and excitement had fatigued even the elephant;

and after a short but brilliant musical entertainment in their

own parlor, the excursionists went to bed.

Renovated by a night of sound sleep, invigorated by the mountain

air and a strong breakfast, the excursion went forth to greet

the morning sun with unabated ardor.

The Alleghanies were behind them—westward ho! Seven miles

from Grafton they tarried to enjoy one of the most exquisite bits

of scenery which had yet met their eyes: the Valley Falls, where

the river takes two leaps, in quick succession, of ten or twelve

feet each, and then descends in long rocky rapid some seventy

feet in a mile.

As we leave the mountains the traits of ruggedness and sublimity

disappear, and the country assumes those softer characteristics

which obtained for the Ohio the name of "La belle Riviere."

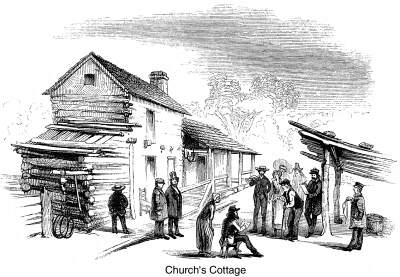

A short distance beyond Burton the train was stopped to give

the excursionists an opportunity of visiting a couple who, from

their extreme old age, have considerable local notoriety. Their

cottage stood immediately by the way-side; and the old folks,

with several of the younger fry, were at home, rather astonished,

no doubt, at the number and character of their visitors.

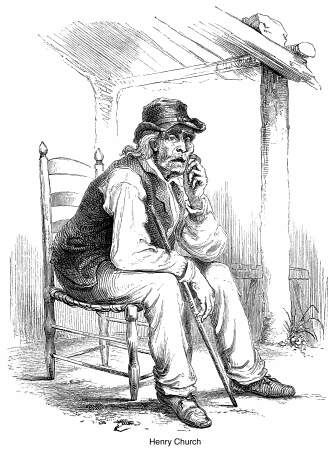

Henry Church was born in Suffolk, England, in the year of our

Lord 1750, and is now a hundred and eight years old. He came to

this country a British soldier, of the 63d Light Infantry, and

served under Lord Cornwallis in the memorable campaign of 1781.

But it was not his fortune to have seen that great day of glory

and disaster at Yorktown which terminated that campaign, and with

it the War of Independence. A short time previous, while on a

scouting-party between Richmond and Petersburg, he was taken by

the troops under Lafayette, and sent a prisoner to Lancaster,

Pennsylvania. He remained here until peace was proclaimed; but

the general amnesty brought no freedom for the captive Briton.

He had become entangled in a flaxen net stronger than the bonds

of way, and the meek eyes of a Quaker maiden had more enduring

power than the bayonets of the  patriot regiments. Forgetting his loyalty to King and

country, the ex-soldier embraced the sweet incarnation of peace,

and bowed his martial neck to the gentle yoke, which he has worn

with exemplary patience and constancy for seventy-and-seven years.

Hannah Keine, the amiable Friend whose charms have so long led

captivity captive, was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in

1755, and is at this day one hundred and three years of age. She

is erect, active in her movements, in full possession of all her

faculties, and is still the tidy, thrifty, bustling mistress of

the household she has ruled for more than three-quarters of a

century. Eight children are the fruits of this union, the eldest

of whom is in his seventy-sixth year; the youngest is fifty-four.

Six of these have married, and the aggregate result is sixty-two

grandchildren. One died, we are told, when between fifty and sixty

years old, and the sorrowing mother was heard to say, in a tone

of resignation,

patriot regiments. Forgetting his loyalty to King and

country, the ex-soldier embraced the sweet incarnation of peace,

and bowed his martial neck to the gentle yoke, which he has worn

with exemplary patience and constancy for seventy-and-seven years.

Hannah Keine, the amiable Friend whose charms have so long led

captivity captive, was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in

1755, and is at this day one hundred and three years of age. She

is erect, active in her movements, in full possession of all her

faculties, and is still the tidy, thrifty, bustling mistress of

the household she has ruled for more than three-quarters of a

century. Eight children are the fruits of this union, the eldest

of whom is in his seventy-sixth year; the youngest is fifty-four.

Six of these have married, and the aggregate result is sixty-two

grandchildren. One died, we are told, when between fifty and sixty

years old, and the sorrowing mother was heard to say, in a tone

of resignation,

"Well, it was always a weakly child, and I never expected

to raise it."

Their daughter, Hannah, still lives a maiden, and true to her

filial duties. She is now "hard on" to sixty; and as

we saw her tripping, barefoot, from the corn patch (where she

had been hoeing), we were not impressed with the idea that Time

had been anywise lenient in his dealings with her. In view of

these things, some good-natured neighbor lately ventured to suggest

that it was high time she was looking out for a settlement, and

following the example of her brothers and sisters.

"Ah!" said the old man, I hope she'll have the grace

to wait till I am gone. It can't be many years now. But,"

he continued, with a sigh, "who knows? These young gals are

uncertain!"

Then we were reminded of the ancient arrow-maker and his touching

grief—

"Thus it is our children leave us!"

The company

has paid its respects to the incarnate centuries, and the artists,

with rapid pencils, are making notes of the scene. In the centre

is the old man, bowed upon his staff, and holding to his wife's

arm, as she stands stark and stiff, like an umbrella stuck into

a blue cotton case—for superfluity of skirts and crinoline

were not of her day and generation. His iron frame is evidently

yielding to the weight of years. Deaf, dim-eyed, his heavy jaw

relaxed, his face wears ordinarily a look of vacuity; but bring

him a goblet crowned with generous wine, or, what is more potent,

though less poetical, a tin of old whisky—the milk of age—his

hearing and eyesight will quickly improve, and he will discourse

freely and intelligently of his past life; speaking of men and

things belonging to our early history as the occurrences and acquaintances

of yesterday.

The company

has paid its respects to the incarnate centuries, and the artists,

with rapid pencils, are making notes of the scene. In the centre

is the old man, bowed upon his staff, and holding to his wife's

arm, as she stands stark and stiff, like an umbrella stuck into

a blue cotton case—for superfluity of skirts and crinoline

were not of her day and generation. His iron frame is evidently

yielding to the weight of years. Deaf, dim-eyed, his heavy jaw

relaxed, his face wears ordinarily a look of vacuity; but bring

him a goblet crowned with generous wine, or, what is more potent,

though less poetical, a tin of old whisky—the milk of age—his

hearing and eyesight will quickly improve, and he will discourse

freely and intelligently of his past life; speaking of men and

things belonging to our early history as the occurrences and acquaintances

of yesterday.

Among the excursionists was an attaché, of the British

Legation at Washington—a young soldier decorated for gallant

conduct on the bloody parapets of the Redan.

"Father Church, let us introduce a countryman—an

Englishman, and a soldier like yourself."

The old man took the extended hand mechanically, but his dull

eyes gave us no sign.

"Bring here the bugle."

The instrument was brought, and the young officer sounded one

of the martial airs of England. Old Hundred stood up as if his

blood had been warmed with wine, and his face flashed with intelligence.

"I know it—I know it—An Englishman and a soldier

did you say? Ay, and a brave lad, I'll warrant."

It was a touching and thought-compelling scene to see these

two together. The old man, eighty years ago, had landed on our

shores an armed invader to aid in crushing out the spirit of revolt

in the feeble and disorganized colonies that bordered the Atlantic

coast. With the sound of that martial bugle call he doubtless

hears the roll of musketry and the deep growl of cannon. Unconscious

of the misty present, he sees with the eyes of youth the scarlet

battalions of his King marching and maneuvering in vain to force

the wary and vigilant host of the rebels to untimely battle. Cornwallis,

Tarleton, Lafayette, Lee—these are the names that fill his

thoughts. With all these memories fresh in his brain he stands

face to face, grasping the hand of the youth, who, member of a

lordly embassy, has come to bear friendly greeting from Old England

to the Great Nation of the western continent—a nation whose

bounds extend from ocean to ocean; whose ships are in every sea;

whose civilization, illuminating the breadth of the New World,

reflects back upon the Old, light for light.

Before the last royal soldier that treads our soil shall have

passed away may the memory of oppression, war, and hatred sink

into the grave of oblivion; while hopeful, strong, and true as

youth, may friendship spring between nations of kindred blood,

laws, language, and religion!

Although the culminating point of scenic interest was past,

the social life of the excursion had on the fourth day reached

its most attractive stage. No friendship can be considered as

firmly cemented until the parties have mutually confided to each

other their little weaknesses and peccadilloes-their loves and

debts, hopes and disappointments. No social community can be regarded

as thoroughly mixed and mellowed until the members permit themselves

unreservedly to make puns. It is a symptom that folks have agreed

to lay aside the panoply of ceremony, generally irksome to all

except those who have nothing else to wear. Dr. Johnson, the Ursa

Major of English letters, said that a punster would steal. Dictionaries

define punning as "a low species of wit." Heaven preserve

our social life from lump-headed learning! We think a discreet

punster a treasure in any company; a timely pun; very good wit;

a bad one, very good humor—the worse the better.

At the Broad

Tree Tunnel, instead of diving through the mountain, the excursion

passed over it by the zigzag road which bad been used before the

completion of the more direct subterraneous passage. To perform

this two additional engines were brought into service. The train

divided into three parts, and each engine taking charge of its

portion, began the ascent of the hill by a grade of 250 feet to

the mile.

At the Broad

Tree Tunnel, instead of diving through the mountain, the excursion

passed over it by the zigzag road which bad been used before the

completion of the more direct subterraneous passage. To perform

this two additional engines were brought into service. The train

divided into three parts, and each engine taking charge of its

portion, began the ascent of the hill by a grade of 250 feet to

the mile.

The novelty of the passage so exhilarated the wits of the company

that the puns rained, in numbers and brilliancy reminding one

of the meteoric shower of 1836, which so astonished the negroes

in Virginia and the savants all over the world. They crackled

like a bunch of Chinese firecrackers let off in an empty barrel.

Who lit the match? We don't know. Doubtless one of the literary

men who remembered a couplet in "The Child's Own Book."

"YY. U. R. YY. U. B,

I. C. U. IL YY. for me."

The track over the hill is laid in the form of YYY connected in a regular zigzag. Upon that hint every body spoke

at once. The consequences were charming, delightful, sublime;

ay, and a step beyond. We can not recall half the good things

that were said; we would not repeat them if we could. The confidence

of these jolly and unguarded moments should be inviolate. Besides,

many a savory dish is relished warm, which, if served cold, might

be thought little better than an emetic.

At length the train reached the banks of the Ohio, and the

eyes of many of the excursionists rested for the first time on

the beautiful River of the West. From thence to Wheeling the road

follows the course of the stream at Moundsville, passing in sight

of the Indian tumulus, seventy feet in height. Although this is

one of the points of especial interest the excursion did not stop

to examine it, but hurried on to the termination of their trip.

As they entered the town of Wheeling the President of the Committee

on toasts arose, and, with a sparkling bumper in one hand, proposed

the three hundred and seventy-ninth regular toast (being one for

every mile of the road), with the understanding that it was positively

to be the last. The sentiment was received with immense applause—which

applause was reinforced by a thundering salute of cannon from

without. The excursion was handsomely received by the Railroad

Company's officials, and conveyed from the depot to the "M'Clure

House" in several omnibuses furnished for the occasion.

Here they reposed for a time, for the mid-day heat was oppressive,

and it was not until toward the middle of the afternoon that they

again ventured out in detached parties—in carriages or afoot—to

see the Lions. Wheeling is famous for its thriving manufactories

of glass and iron, and is equally renowned for the free and genial

hospitality of its citizens. The town is like many a child we've

seen, that would be very pretty if its face was washed. But in

recompense its environs are beautiful. The bold bluffs of the

Ohio, softened with the tender leafage of June, fully justify

the fame of the lovely river, while a drive across the noble suspension

bridge to Zanes Island and the agricultural fair grounds well

repays the trouble. Behind the town is Wheeling Hill, from whose

summit the view is extensive, grand, and unique.

As we returned to the "M'Clure House" about dark

we met a friend who saluted us with a joyful countenance.

"Comrade," said he, "I have discovered a new

pleasure—come share it with me."

"What's that?"

"A Catawba cobbler."

"Bravissimo! lead the way."

So the cobblers were manufactured, and a plump strawberry dropped

into each glass among the tinkling ice.

"I've had eight already," quoth my friend, each better

than the other."

"Oh, Hebe! what a drink! This is the wine that Longfellow

has poetized:

"Very good in its way

Is the Verzenay,

Or the Sillery soft and creamy;

But Catawba wine

Has a taste more divine,

More dulcet, delicious, and dreamy.

"There grows no vine

By the haunted Rhine,

By Danube, or Guadalquiver,

Nor on Island or Cape

That bears such a grape

As grows by the beautiful river."

"Eight are enough," observed my friend, with a touch

of sadness in his voice. "At nine they begin to deteriorate.

Nine, this time, was a trifle too acid."

In due time an elegant supper was served which was disposed

of in a most satisfactory manner, highly creditable to all parties.

Then followed a hospitable welcome from the venerable Mayor of

Wheeling, with toasts, speeches, and compliments right and left.

Every body was pleased, charmed, delighted with every body else,

with every thing, with themselves, the road, and the excursion

generally. Hip—hip—hip—hurrah!

At eleven o'clock the company re-embarked, and started on their

return eastward. If during the four days of leisurely movement

we had been delighted with the examination of the details of the

road, and impressed by the sublimity of its natural surroundings,

yet the wonderful character of the achievement was more fully

realized by the rapid, unbroken sweep over the whole length of

the rail from Wheeling to Baltimore, 379 miles in 16 hours, without

an incident, a jolt, or the slightest discomfort.

On the 5th of June the company arrived at the Camden Street