|

||||||

| ||||||

|

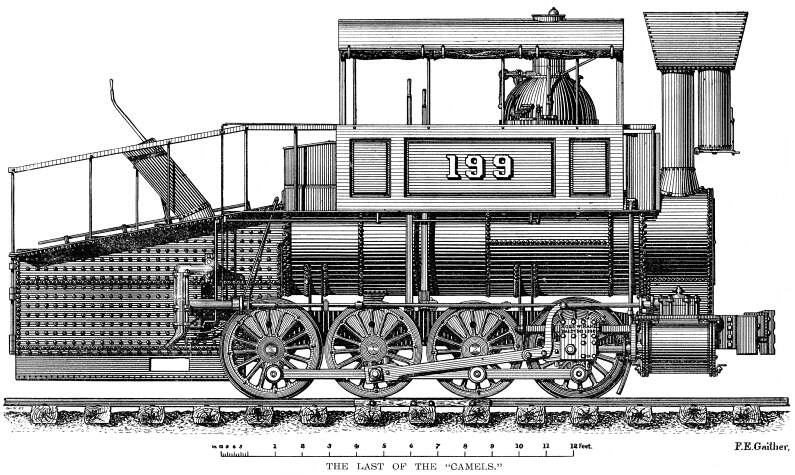

The Railway Master Mechanic—December, 1891 We give this month an excellent illustration of one of a lot of three Ross Winans "camel" locomotives which were the last of that type ever built at the shops in which the type originated. We are indebted to Mr. J. Snowden Bell for the drawing from which the engraving was made and for many of the details given in this article. Mr. Bell published an article in the Journal of the Franklin Institute for October, 1878, entitled, "The 'Camel' Engine of Ross Winans," in which he gave much valuable information concerning the early history of this type of locomotive. Mr. Bell's paper informs us that the first eight-wheel connected locomotive was called the "Buffalo," and was built by Ross Winans in 1844 for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. A six-wheel connected engine had been constructed by M.W. Baldwin, of Philadelphia, two years previously, and eight-wheelers were built by Baldwin in 1846. The Baldwin six and eight-wheelers seem to have proved better machines than the Winans eight-wheeler of 1844 ("mud diggers" they were called), the drivers of which were coupled to a counter shaft placed at the rear of the fire-box and geared to the engine shaft, and to better meet the competition Mr. Winans designed the "camel," 219 of which were built between June, 1848, and February, 1857. Of these, 119 went on the Baltimore & Ohio, and the others were scattered over many roads, among them the Pennsylvania, Philadelphia & Reading and New York & Erie. When the war broke out Winans' shops were closed, and the three engines mentioned at the beginning of this article were left in stock. It is said that some negotiations for their purchase were had with the U. S. government, but the national authorities demanded some sort of a guarantee of Winans' "loyalty." Winans seems to have been a strong "secesh" sympathizer, and his refusal to give a certificate of loyalty to the government is said to have been surrounded and made complete by a profanity which had all the standard measurements and all the modern improvements. The engines were finally bought by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co., the price paid being $27,000. The statement of such prices will send cold chills of envy and regret down the backs of the locomotive builders of to-day, though high prices for engines did not end with the war by any means, and some of those in the business today have in a more recent past taken wide strips of fat even when the lean was very satisfactory in quantity and quality. Mr. Winans refused to sell the three camels unless the company would also buy the "Centipede" which was an eight-wheel connected engine with a four-wheel truck. This engine gave a great deal of trouble and soon went to the scrap heap. Mr. Cromwell, now one of the superintendents of motive power of the road, had an intimate acquaintance with it. It is said that his hair stands up straight and that he involuntarily drops on his knees to this day, when he thinks of how she used to run backward down the mountain on a grade of 117 feet to the mile an 17 miles long. We think that the "hair" part of he story is exaggerated. In the article already mentioned, Mr. Bell calls attention to the following features (some of which are now in general use) which were novel at the time, and distinguished the "camels" from previous constructions:

1. The employment of eight driving wheels, set closely between horizontal cylinders and a long overhung firebox, the width of which is equal to or greater than the distance over frames. 2. A fire-box having a downwardly and rearwardly inclined top. 3. A dome and an engineer's house placed on top of the boiler close to the forward end. 4. An upper chute for feeding coal through the top of the firebox. 5. A fire-box having no water space on its rear side, which was closed by doors, so as to expose its entire area when required. 6. The abandonment of crown sheet stay bars, and the substitution of stay bolts connecting the crown sheet with the outer shell. 7. The use of a half-stroke cam as a means of effecting cut-off. All these engines were substantially of the same pattern, except as to the fire- box, of which there were three classes, the short, medium and long; the latter which is shown in the illustration, having as great a length as 8 ft. 6 in. and a width of 4 ft. The grate surface of the medium class was 6 x 3½ ft., giving the then enormous area of 21 sq. ft. The boiler, of 5-16 iron, was 46 in. in diameter. The cylinders, (except in a few of the earlier engines, which were only 17 in.) were 19 in. in diameter, and 22 in. stroke, and the diameter of the driving wheels in all cases was 43 in., with an extreme wheel base of only 11 ft. 3 in. The front and rear wheels only were flanged, and end play was left in the boxes, to admit of the passage of the engines around curves. Chilled cast iron tires were used, fastened by hook-headed bolts, passing between the center and tire, and, in the earlier engines, chilled wheels without separate tires were employed. The weight of the engines varied from 25 to 29 tons (of 2000 lbs.). The valve motion was of the old "drop hook" pattern and the valves could be operated either by an eccentric or a half-stroke cam for cutting off, as desired. The performance of these locomotives was very satisfactory. They hauled eight twenty ton loaded freight cars up grades of 116 ft. to the mile and around curves of 600 ft. radius. For a considerable period an engine of this type hauled on a temporary track one loaded freight car up a grade of 528 ft. to the mile, with curves of 300 and 400 ft. radius, at a speed of 13 miles per hour. It would seem that the camel in those days occupied somewhat the position which the consolidations and moguls occupy in the service of to-day. The latest design of the camel as shown in the cut, had some features not noted by Mr. Bell in his article, but which are referred to by him in a recent letter to this paper. The construction of the stack is very peculiar. The upright portion—or stack proper—opened into a box from which a "dirt pipe" projected downwardly and served as a receptacle for cinders. The pump rods in the earlier camels were in the same horizontal plane as the valve stems and were worked from the crossheads. The later engines had arms bolted to the main rods close to the crossheads, and the pump rods were connected to the upper ends of these arms. The fire-box is seen through the spokes of the rear driving wheel to be of irregular shape at the front end, a construction which made a short combustion chamber in the front end of the fire-box. This feature was patented by Mr. Winans in 1854, and was, Mr. Bell says in his article, substantially adopted by James Milholland, master of machinery of the Philadelphia & Reading, and the use of it has continued up to this time. The standard Pennsylvania Railroad "consolidation" of 1875 had, substantially the Winans inclined fire-box. Some of the innumerable friends of Mr. Morris Sellers, whose geniality "time cannot wither nor custom stale," have laughed to hear him tell of the fun he had (many, many years ago, alas!) in getting a "camel" out of the roundhouse in Altoona in a hurry. It was his first, last and only experience in running one of these engines—short, but intense. He had gone to Altoona to get a position in the motive power department (in which he succeeded a few days later), and was looking over the engines in the roundhouse when "Andy" Vauclain, who had charge of all the freight engines, rushed in and ordered a locomotive to get out in a hurry to help clear up a wreck just west of Altoona. No. 52, a "camel," was ready for the road, but there was no engineer in sight, and Vauclain asked Sellers, who was then an experienced engine runner, if he would not take it out. Sellers had too much pride to suggest that he had never run a camel, and immediately went to the front end and climbed into the cab, away up on the poop deck. He says that he began to sweat as soon as he looked around. To start one of those machines was almost as much of an operation as to get a full rigged ship under way. The engine's valves were operated by the old fashioned hooks, and he had first to take a long and heavy "starting bar," 13 ft. long, get one end of it down into the socket of the rocker and then work it to throw the cams until the hook "caught on." (The socket is shown in the cut between the second and third driving wheels, and just above the long pump rod, with the starting bar standing in it and extending up into the cab.) Next he had to climb over the boiler to the other side of the cab and go through the same process on that side of the engine. Then he had to "give her steam." The throttle valve lever was a two handed affair, like those levers with which section hands pump speed into hand-cars. The lever connections had two or three right angles in them with a joint at each one, and the amount of lost motion between the handle and the valve was surprising. The latter was a "gridiron," and when it began to open so that the steam could get hold of it, it went wide open with a bang. He, of course, had had no practice in manipulating this throttle, and allowing for the lost motion in the connections, and consequently when the Irishman at the turntable said, "All ready, sure," he hoisted away on the throttle lever till it neared the roof the cab; the valve suddenly opened wide, giving a full head of steam, and the engine started with a jump, which, Mr. Sellers says, brought his heart up into his throat. He thought surely the old camel would shoot across the turntable and go through the other wing of the roundhouse. However, he managed to shut off steam and stop her, as he thought, fairly on the turntable. And when a voice called out from below, with a rich brogue, "About 4 feet more, surr," he was ready to lie down and die! "If it had been 4 miles," he says, "I should have felt all right—but 4 feet! I was too proud to call for a pinch bar and I wished that I had never seen Altoona." However, he managed to work the engine on to the table by steam, and after that he had a clear track and the worst of his troubles were over. After nearing the wreck he had to pull a very long freight train up a very steep grade and by a cross-over to the other track, and he says that he was simply astounded by the power which the locomotive developed in that kind of work. We shall be glad if this article and illustration call out other reminiscences of experiences with this type of locomotive, now obsolete.

B & O RR | Antebellum RR | Contents Page |

||||||

|

|

|

|||||