|

EARLY DAYS ON THE ERIE

Text from—"When Railroads Were New"—by Charles Frederick

Carter--1909

THE first bride who ever made a honeymoon trip on a railroad

in America did more by that act to expedite the building of the

world's first trunk line than the ablest statesmen, engineers,

and financiers of the Empire State had been able to accomplish

by their united efforts in half a dozen years.

Indeed, it is within bounds to go much further than this and

say that the inspiration drawn from this bride's delight over

her novel ride pushed the hands of progress ahead ten years on

the dial of history.

The bride who achieved so much was Mrs. Henry L. Pierson, of

Ramapo, N. Y. Mr. and Mrs. Pierson were in Charleston, S. C.,

early in January, 1831, on their wedding tour. When Mrs. Pierson

heard that a steam locomotive was to make its first trip with

a trainload of passengers over the South Carolina Railroad from

Charleston to Hamburg, six miles away, on January 15, she was

eager to take the ride; and her husband, like a dutiful bridegroom,

agreed.

That was the first regular train that ever carried passengers

in the United States. It was then less than eighteen months from

the time when the first successful locomotive had made its trial

trip.

The locomotive which drew the first regular passenger train

in America and the first bridal couple to take a railroad journey

was the Best Friend of Charleston.

The two cars were crazy contraptions on four wheels, resembling

stagecoach bodies as much as they did anything else. The train

contrived to get over the entire system of six miles and back

again at a fairly satisfactory speed.

All the passengers were highly pleased with their strange experience.

The bride was in a transport of delight. She could talk of nothing

else. When she returned to Ramapo she gave her brother-in-law,

Eleazer Lord, and her father-in-law, Jeremiah Pierson, such glowing

accounts of her railroad trip that they were fired with enthusiasm.

The bridegroom had already become almost as ardent an advocate

of railroads as his bride.

Jeremiah Pierson, the father of the bridegroom, was one of

the nation's first captains of industry. He owned several thousand

acres of land around Ramapo, on which he conducted tanneries,

a cotton-mill, iron-works, and a nail factory. His son-in-law,

Eleazer Lord, was one of the leading merchants, financiers, and

public men of New York City.

For half a dozen years the two had been deeply interested in

Governor De Witt Clinton's ideas for the development of southern

New York by means of a State highway or canal or other method

of communication, but politicians in central New York, where the

Erie Canal had been in operation from 1825, by methods not unknown

even among politicians of today, turned all the efforts of the

Governor and his public-spirited supporters into a farce.

Later, Mr. Lord and his father-in-law had been greatly interested

in the possibilities of a railroad as the best form for Governor

Clinton's proposed highway to take. But their original idea of

a railroad was an affair of inclined planes and horse-power.

Of course, they had heard all about the experiments with locomotives

and the building of the South Carolina Railroad, the first in

the world projected from the outset to be operated by steam locomotives,

and they had been deeply interested in William C. Redfield's famous

pamphlet, so widely circulated in 1829, proposing a steam railroad

from the ocean to the Mississippi; but the idea of a steam road

through southern New York was not clearly developed in their minds

until the bride's glowing accounts of her experience fired their

imaginations.

Young Mrs. Pierson gave it as her opinion that if a steam railroad

were built it would be possible to go from New York to Buffalo

in twenty-four hours. At first, the men folks were inclined to

smile at this, but they were thoroughly impressed with the value

of the locomotive as described by this ardent advocate.

Mrs. Pierson's girlish enthusiasm was the determining factor

which crystallized the ideas of those men and led them to take

the steps which finally resulted in the building of what is now

known as the Erie Railway, which, by uniting the ocean with the

Great Lakes, became the world's first trunk line.

No railroad has had a more romantic history than this one,

which had its inception in so romantic an incident. It required

twenty years of toil and anxiety, sacrifice and discouragement,

to get the line through, but it was accomplished at last, and

the bridegroom and bride who had made the memorable first wedding

journey by rail were again passengers on a trip which will live

in history as long as railroads exist.

This time the bride was a handsome woman of middle age, but

she was just as proud of her husband as she was on that first

trip, for he was vice-president of the road, the longest continuous

line in the world, and the trains did move at a speed that would

have carried them from New York to Buffalo in twenty-four hours,

just as she had prophesied two decades before that they would.

Mr. Lord at once began corresponding with the most influential

citizens of southern New York on the subject of building a steam

railroad from the ocean to the Lakes. The idea was well received

everywhere; so well, in fact, that a public meeting in furtherance

of Mr. Lord's railroad scheme was held at Monticello, July 29,

1831; another at Jamestown, September 20, and a third at Angelica,

October 25. Finally, a great central convention was called to

meet at Oswego, December 20, 1831.

People were inclined to believe that so vast an enterprise

as the building of five hundred miles of railroad was too much

for one company to undertake. It was pretty generally believed

that two companies would be required—one to build from New

York to Oswego, the other from Oswego to Lake Erie.

A convention at Binghamton, December 15, had formally approved

the two-company plan, and public opinion had pretty definitely

decided that two companies were necessary.

But while the Oswego convention was in session a citizen rushed

breathlessly in, interrupting a delegate who was delivering an

address, and in the most orthodox style known to melodrama handed

the president a letter. It was from Eleazer Lord, briefly but

emphatically declaring that the undertaking could be carried to

success only by a single corporation.

His reasoning was so cogent that the convention without much

ado decided in favor of one corporation, and nothing further was

heard of the two-company proposition.

Public opinion was so pronounced in favor of the railroad that

the politicians from the canal counties could make no headway

against it. A charter drafted by John Duer, of New York, was granted

the New York and Erie Railroad, April 24, 1832.

But the fine Italian hand of the politicians who could not

prevent the granting of the charter was clearly to be seen in

the document itself. That instrument provided that the entire

capital stock of ten million dollars must be subscribed and five

per cent of the amount paid in before the company could incorporate.

The canal counties had served public notice that the projectors

of this great public work would have to combat all the pettifogging

intrigues of which small politicians were capable before they

could even begin their titanic contest with nature.

The little band of enthusiasts led by Eleazer Lord were undertaking

the most stupendous task that had been set before the nation up

to that time. The country was poor in resources; the region through

which the road was to run was a wilderness except for a few scattering

villages.

Missouri was the only State west of the Mississippi. Chicago was

a village clustered around Fort Dearborn. Railroad building was

an unknown science three-quarters of a century ago. The building

of five hundred miles of road then was a far more stupendous task

than the building of ten thousand miles would be to-day.

Seeing the hopelessness of complying with the terms of the

charter, the incorporators contrived to bring enough pressure

to bear on the legislature to have the amount of subscription

required before organization reduced to one million dollars.

Finally, on August 9, 1833, the New York and Erie Railroad

Company was organized, with Mr. Lord as president. The next month

the board of directors issued an address asking for donations

of right of way and additional donations of land.

As no survey had been made, and no one had any idea where the

road would be located, this address failed to bring out either

donations or subscriptions of stock, but there was a great deal

of harsh talk about land-speculation schemes.

In desperation, a convention was held, November 20, 1833, in

New York City, to ask for State aid. The aid was not forthcoming.

Next year the company took the little money received for stock

from the incorporators and started the surveys. The eastern end

of the line began in a marsh on the banks of the Hudson, twenty-four

miles north of New York City.

Considering that the fundamental purpose of the road was to

secure the trade of the interior to New York, this did not make

any new friends for the road. The western end of the road was

to be Dunkirk, a village of four hundred inhabitants, on the shores

of Lake Erie.

The talk about land speculation and the failure to make satisfactory

progress created such strong opposition to his policy that Mr.

Lord resigned as president at the January meeting in 1835, and

J. G. King was elected to succeed him. King, by superhuman exertions,

was able to make an actual beginning.

He went to Deposit, some one hundred and seventy-seven miles

from New York, where at sunrise on a clear, frosty morning, November

7, 1835, on the eastern bank of the Delaware River, be made a

little speech to a party of thirty men, in which he expressed

the conviction that the railroad for which be was about to break

ground might in a few years earn as much as two hundred thousand

dollars a year from freight.

This roseate prophecy being received with incredulity, Mr.

King hastened to modify it by saying the earnings might amount

to so vast a sum "at least eventually." Then he shoveled

a wheelbarrow-load of dirt, which another member of the party

wheeled away and dumped, and the great work was begun.

But it was only begun. No progress was made that year, nor

did it look as if any further progress ever would be made. The

great fire in New York, December 16, 1835, ruined many of the

stockholders, and the panic of 1836-1837 bankrupted many more.

Once more the company resolved to appeal to the legislature

for aid as a last desperate expedient. The sum required was fixed

at three million dollars.

Although the request was supported by huge petitions from New

York, Brooklyn, and every county in the southern tier, the opposition

was bitter. However, public opinion was too strong to be ignored,

so the opposition went through the form of yielding to popular

clamor by presenting a bill to advance two million dollars when

the company had expended four million six hundred and seventy-four

thousand five hundred and eighteen dollars.

This was a safe move, because the company had not a dollar

in the treasury, and no means of getting one. Subsequently the

conditions were modified and the credit of the State to the amount

of three million dollars was loaned. Ultimately the amount was

given outright.

In December, 1836, the board issued a call for a payment of

two dollars and a half a share. Less than half the stockholders

responded. Then a public meeting was held, at which a committee

of thirty-nine was appointed to receive subscriptions. The committee

opened its books and sat down to wait for the public to step up

and subscribe. The public didn't step.

By 1838 President King had had enough of the effort to materialize

a railroad out of the circumambient atmosphere, and the board

of directors again turned to Eleazer Lord, who had a new plan

to offer. It was to let contracts for the first ten miles from

Piermont, the terminus of the road on the Hudson, twenty-four

miles above New York, and solicit subscriptions in the city to

pay for that amount of work, and to solicit subscriptions from

Rockland and Orange counties to pay for the next thirty-six miles,

to Goshen. Middletown was to be asked to pay for nine miles between

that point and Goshen.

Before this plan could be put in operation, the company had a

very narrow escape from an untimely end. People were getting so

impatient to see some progress made that the legislature of 1838-1839

was swamped with petitions for the immediate construction of the

road by the State.

February 14, 1839, a bill authorizing the surrender by the

New York and Erie Railroad Company of all its rights, titles,

franchises, and property to the State was defeated in the Senate

by the narrow margin of one vote.

The Assembly succeeded in passing a similar bill, but it was

defeated in the Senate, seventeen to twenty-four. The Governor

stood ready to sign the bill if it had been adopted by the legislature.

In the spring of 1839 grading was begun under Lord's newest

plan. October 4, 1839, Lord was again made president, and H. L.

Pierson, who with his bride had taken that historic ride on the

first passenger train, was made a director. Mr. Lord continued

to keep things moving in his second administration so effectively

that on Wednesday, June 30, 1841, the first trainload of passengers

that ever traveled over the Erie Railroad was taken to Ramapo,

where the party was entertained by the venerable Jeremiah Pierson,

the father-inlaw of the bride who made the memorable trip ten

years before, who was one of the directors of the road. Three

months later the line was opened for traffic to Goshen, forty-six

miles from Piermont.

Slowly, very slowly, the rails crept westward. Not until December

27, 1848, more than seven years after reaching Goshen, did the

first train enter Binghamton, one hundred and fifty-six miles

beyond. In all those seven years the Erie Company was experiencing

a continuous succession of perplexities, annoyances, difficulties,

and dangers that in number and variety have probably never been

equaled in the history of any other commercial enterprise in this

country.

The financing of the work was one prolonged vexation. Times

innumerable it seemed as if the whole enterprise must fail for

want of funds, but at the last minute of the eleventh hour some

way out would be found.

Then, too, the company had to learn the science of railroading

as it went along. There was no telegraph in those days to facilitate

the movement of trains. The only reliance was a time card and

a set of rules.

Locomotives and rolling stock were small and crude. Officials

and employees had everything to learn, since railroads were new,

and every point learned was paid for in experience at a good round

figure. The living instrumentalities through which the evolution

of the railroad was achieved were very much in earnest, as they

had need to be. They were too busy with the problems of each day

as they arose to glut their vanity with profitless reflections

upon the magnificence of the task upon which they were engaged,

or to enjoy the humor of the expedients which led to their solution.

Posterity gets all the laughs as well as the benefits.

An interesting example of the quaint devices by which important

ends were attained is afforded by the origin of the bell cord,

the forerunner of the air whistle, now in universal use on American

roads for signaling the engineer from the train. A means of communication

between the engine and the train has always been considered indispensable

in America. In Europe the lack of such means of communication

has been the fruitful source of accidents and crimes.

The bell cord was the invention of Conductor Henry Ayers, of

the Erie Railroad. In the spring of 1842, soon after the line

had been opened to Goshen, forty-six miles from the Hudson River,

there were no cabs on the engines, no caboose for the trainmen,

no way of getting over the cars, and no means of communicating

with the engineer. There were no such things as telegraphic train

orders, no block signals, no printed time cards, no anything but

a few vague rules for the movement of trains. The engineer was

an autocrat, who ran the train to suit himself. The conductor

was merely a humble collector of fares.

Conductor Ayers, who afterwards for many years was one of the

most popular men of his calling in the country, was assigned to

a train whose destinies were ruled by Engineer Jacob Hamel, a

German of a very grave turn of mind, fully alive to the dignity

of his position, who looked upon the genial conductor with dark

suspicion. When Ayers suggested that there should be some means

of signaling the engineer so he could notify him when to stop

to let off passengers, suspicion became a certainty that the conductor

was seeking to usurp the prerogatives of the engineer. Hamel decided

to teach the impertinent collector of small change his place.

One day Ayers procured a stout cord, which he ran from the

rear car of the train to the framework of the cabless engine.

He tied a stick of wood on the end of the cord, and told Hamel

that when he saw the stick jerk up and down he was to stop. Hamel

listened in contemptuous silence, and as soon as the conductor's

back was turned threw away the stick and tied the cord to the

frame of the engine. Next day the performance was repeated.

On the third day Ayers rigged up his cord and his stick of

wood before starting from Piermont, the eastern terminus, and

told Jacob that if be threw that stick away he would thrash him

until he would be glad to leave it alone.

When they reached Goshen the stick was gone, as usual, and

the end of the cord was trailing in the dirt. Ayers walked up

to the engine, and without saying a word yanked Hamel off the

engine and sailed in to thrash him. This proved to be no easy

task, for Hamel had all the dogged tenacity of his race. But one

represented Prerogative, while the other championed Progress,

and Progress won at last, as it usually does.

That hard-won victory settled for all time the question of

who should run a train. Also it showed the way to a most useful

improvement. Once the idea was hit upon it did not take long to

replace the stick of wood with a gong. In a very short time the

bell cord was in universal use on passenger trains.

To Conductor Ayers is also due the credit of introducing another

new idea, which, if not so useful in the operation of trains,

was at least gratefully appreciated by a numerous and influential

class of patrons: the custom of allowing ministers of the Gospel

half rates.

Early in the spring of 1843 the Rev. Dr. Robert McCartee, pastor

of the Presbyterian Church at Goshen, was a passenger on Conductor

Ayers's train. On account of a very heavy rain the track was in

such bad condition that the train was delayed for hours. The passengers,

following a custom that has been preserved in all the vigor of

its early days, heaped maledictions upon the management. Some

of the more spirited ones drew up a set of resolutions denouncing

the company for the high-handed invasion of their rights, as manifested

in the delay, in scathing terms. These resolutions were passed

along to be signed by all the passengers. When Dr. McCartee was

asked for his signature, he said he would be happy to give it

if the phraseology was changed slightly. Upon being requested

to name the changes he wished, he wrote the following:

"Whereas, the recent rain has fallen at a time

ill-suited to our pleasure and convenience and without consultation

with us; and

"Whereas, Jack Frost who has been imprisoned in

the ground some months, having become tired of his bondage, is

trying to break loose; therefore be it

"RESOLVED, that we would be glad to have it otherwise."

When the good Dr. McCartee arose and in his best parliamentary

voice read his proposed amendment, there was a hearty laugh, and

nothing more was heard about censuring the management.

Conductor Ayers was so delighted with this turn of affairs

that thereafter he would never accept a fare from Dr. McCartee.

Not being selfish, the Doctor suggested a few weeks later that

the courtesy be extended to all ministers. The company thought

the idea a good one, and for a few months no minister paid for

riding over the Erie. Then an order was issued that ministers

were to be charged half fare. That order established a precedent

which was universally followed until the new rate law put an end

to the practice.

The modest but invaluable ticket punch was also evolved on

the Erie. When the first section of the road was opened in 1841

there were no ticket agents. Each conductor was given a tin box

when he started out for the day, which contained a supply of tickets

and ten dollars in change. The passenger on paying the conductor

his fare received a ticket, which he surrendered on the boat during

his voyage of twenty-four miles down the Hudson from Piermont

to New York. These tickets were heavy cards bearing the signature

of the general ticket agent. These were taken up and used over

and over again until they became soiled.

Travelers soon found a way to beat the company. They would buy

a through ticket which they would show according to custom. At

the last station before reaching their destination they would

purchase a ticket from that station to destination. This latter

ticket would be surrendered and the through ticket kept to be

used over again. The process would be repeated on the return trip.

The passenger would then be in possession of through transportation,

which enabled him to ride as often as he liked by merely paying

for a few miles at each end of his trip.

It was some time before this fraud was discovered. Then a system

of lead pencil marks was instituted, but pencil marks were easy

to erase. The only sort of mark that could not be erased was one

that mutilated the ticket. This led to the development of the

punch.

Another interesting innovation which originated on the Erie

was intended for the laudable purpose of protecting passengers

from the dust which has always been one of the afflictions associated

with railroad travel. A funnel with its mouth pointed in the direction

the train was moving was placed on the roof of the car, through

which, when the train was in motion, a current of air was forced

into a chamber where sprays of water operated by a pump driven

from an axle washed the dust out and delivered the air sweetened

and purified to the occupants of the car. A small stove was provided

to heat the wash water in winter. Several cars were so equipped,

and they seem to have satisfied the demands of the day, for David

Stevenson, F.R.S.E., of England, who made a tour of inspection

of American railroads in 1857, recommended their adoption by English

railroads. But the combined ventilator and washery did not stand

the test of time; and in later years passengers on the Erie, in

common with the patrons of other roads, were obliged to be content

with unlaundered air.

While it was learning the rudiments of railroading the company

acquired some interesting side-lights on human nature, also at

war prices. People of a certain type were eager to have the railroad

built, but they never permitted this eagerness to blind them to

the immediate interests of their own pockets.

One of the natives near Goshen had bought a tract of land along

the right-of-way, expecting to make a fortune out of it when the

road was in operation. The fortune manifested no indications of

appearing until the native observed that the railroad had established

a water-tank opposite his land, which was supplied by a wooden

pump which required a man to operate.

Thereupon the native scooped out a big hole on top of a hill

near by, lined it with clay to make it waterproof, and dug some

shallow trenches from higher ground to the basin, which was soon

filled by the rains.

Then the native went to New York and told the officers of the

road that he had a valuable spring which would afford a much more

satisfactory supply of water than the pump. He would sell this

spring for two thousand five hundred dollars if the bargain was

closed at once.

Commissioners were sent to examine the spring and close the

deal. The two thousand five hundred dollars were paid over, and

the company spent two thousand five hundred dollars more laying

pipes from the "spring" to the track. Of course, the

water all ran out in a short time, and no more took its place.

Then the railroad company found that the land was mortgaged, and

that if they did not get their pipe up in a hurry it would be

lost, too.

A neighbor of this same native had a mill run by water-power,

which had been standing idle for a couple of years. The railroad

skirted the edge of the mill-pond. One day a train got tired of

pounding along over the rough track and plunged off into the mill-pond.

The company asked the owner to let the water off, so that it

could recover its rolling stock. But the mill man suddenly became

very busy, started up his mill, and declared he couldn't think

of shutting down unless he was paid six hundred dollars to compensate

him for lost time. Not seeing any other solution of the difficulty,

the railroad company paid the six hundred dollars.

Going down the Shawangunk Mountains into the Neversink Valley

there was a rocky ledge through which a way had to be blasted.

The German owner of the rocks, when approached by the right-of-way

agents, gave some sort of non-committal reply which was interpreted

as consent. But when the workmen began operations on the rocks

the owner stopped them and would not let them do a stroke until

he had been paid a hundred dollars an acre for two acres of rock

that was not worth ten cents a square mile. All along the line

owners suddenly appeared for land that had been regarded as utterly

worthless who had to be paid extravagant sums for right-of-way

through their property. Fancy prices were also extorted for ties,

fuel, and bridge timbers for the railroad.

Retribution overtook the greedy ones at last. The Irish laborers

employed on the grade overran the country, digging potatoes, robbing

hen-roosts and orchards, and helping themselves to whatever else

took their fancy.

The company had its full share of trouble with these same Irishmen.

Some were from Cork, some were from Tipperary, some from the north

of Ireland, called the "Far-downers," while all were

pugnacious to the last degree. There were frequent factional riots,

in one of which three men were killed.

According to popular report, a good many others were killed and

their bodies buried in the fills as the easiest way to dispose

of them and the chance of troublesome official investigations.

On several occasions the militia had to be called out to suppress

disturbances. Prevention by a general disarmament and the confiscation

of whisky was ultimately found to be the most effective way of

dealing with the turbulent ones.

Still, there were a few incidents of a more agreeable nature.

In 1841, G. W. Scranton, of Oxford, N. J., attracted by the rich

deposits of iron and coal in the Luzerne Valley, Pennsylvania,

bought a tract of land there and established iron-works, where

he was joined later by S. T. Scranton. They had a hard struggle

to keep going for five years.

Then W. E. Dodge, a director in the Erie, who knew the Scrantons,

conceived the idea of having the Scrantons make rails for the

road. The company was having great difficulty in getting rails

from England, and the cost was excessive.

A contract was made with the Scrantons to furnish twelve thousand

tons of rails at forty-six dollars a ton, which was about half

the cost of the English rails. Dodge and others advanced the money

to purchase the necessary machinery, and the rails were ready

for delivery in the spring of 1847. This Erie contract laid the

foundations of the city of Scranton.

To get the rails where they were needed it was necessary to

haul them by team through the wilderness to the Delaware and Hudson

Canal, at Archbold, thence by canal-boat to Carbondale, thence

by a gravity railroad to Honesdale, thence by canal-boat, again,

to Cuddebackville, and finally by team once more over the Shawangunk

Mountains on the western extension, a distance of sixty miles.

By the time the road had reached Binghamton, two hundred and

sixteen miles from New York, the Erie company seemed to be at

its last gasp. Every dollar of the three million that by superhuman

exertion had been raised for construction was gone, and there

seemed no way to raise more.

At the last moment Alexander S. Diven, of Elmira, came to the

rescue with a device which has since become the standard method

of railroad-building. This was a construction syndicate, the first

ever organized. An agreement was made by which the Diven syndicate

was to do the grading, furnish all material except the rails,

and lay the track from Binghamton to Corning, a distance of seventy-six

miles, taking in payment four million dollars in second-mortgage

bonds.

This saved the situation and aroused new interest in the road.

It made fortunes for the members of the syndicate, but it increased

the heavy burden of debt on the company and helped to make trouble

for the future.

In 1849 the company tried the interesting experiment of building

iron bridges. Three of them, the first structures of the kind

ever built for a railroad, were erected during that year. An eastbound

stock train was crossing one of the iron bridges near Mast Hope

July 31, 1849, when the engineer heard a loud cracking. Instantly

divining the reason, he jerked the throttle wide open and succeeded

in getting the engine across in safety. So narrow was his escape

that even the tender of the locomotive followed the train into

the creek along with the wrecked bridge. A brakeman and two stockmen

lost their lives.

This accident caused the company to lose faith in iron bridges.

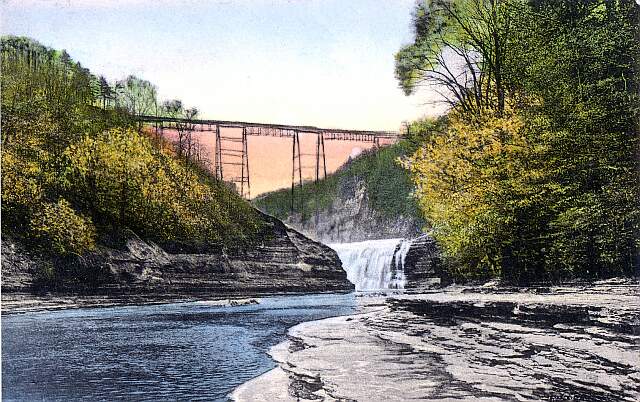

Thereafter all bridges were built of wood, including the famous

structure over the chasm of the Genesee River at Portage. This

chasm was two hundred and fifty feet deep and nine hundred feet

wide. A congress of engineers being assembled to devise means

of crossing it, a wooden bridge in spans of fifty feet was decided

upon.

It required two years' time and an outlay of one hundred and

seventy-five thousand dollars to build. When it was opened August

9, 1852, sixteen million feet of timber, the product of three

hundred acres of pine forest, had gone into the structure. The

science of iron bridge building was making progress; and when

the great wooden structure burned in 1875 it was replaced in forty-seven

days with a modern steel bridge.

The road was completed to Corning on December 31, 1849. By this

time business throughout the country was improving, and the prospects

of the Erie looked brighter.

There now remained a gap of one hundred and sixty-nine miles from

Corning to Dunkirk, on Lake Erie, the western terminus, to be

filled in. But the company having learned how to issue bonds,

the rest seemed easy. An issue of three million five hundred thousand

dollars of income bonds, bearing seven per cent interest, floated

at a heavy discount, followed later on by a second issue of the

same amount, paid for the completion of the work, in the spring

of 1851.

The driving of the last spike, which completed the road that linked

the ocean with the Lakes, marked an epoch in the history of railroads.

The first great trunk line was now ready for traffic. The Pennsylvania

was then only a local line from Philadelphia to Hollidaysburg,

in the foothills of the Alleghanies.

New York was connected with Buffalo by an aggregation of ramshackle

roads of assorted gauges. The only other road of importance in

the world was the line from St. Petersburg to Moscow, which was

opened also in 1851.

So notable an event called for something unusual in the way

of a celebration. Whatever may have been its shortcomings in financial

acumen or constructive genius, and it had many such to answer

for, the Erie management was a past master in the art of celebrating.

Beginning with the opening of the first section of the line to

Ramapo, away back in 1841, every achievement in construction had

been celebrated with great eclat. The completion of the line to

Goshen, to Port Jervis, to Binghamton, to Elmira, the completion

of the Starrucca viaduct and of the wooden bridge over the chasm

of the Genesee at Portage, had all been celebrated with prodigal

pomp.

When the time came that the world's first long-distance railroad

excursion could be made the celebration arranged eclipsed anything

of the kind that had been done. The guests included President

Fillmore, Secretary of State Daniel Webster, Attorney-General

John J. Crittenden, Secretary of the Navy W. C. Graham, Postmaster-General

W. K. Hall, and some three hundred other distinguished guests,

including six candidates for the Presidency, twelve candidates

for the Vice-Presidency, United States Senators, governors, mayors,

capitalists, merchants, and President Benjamin Loder and the other

officers and directors of the company.

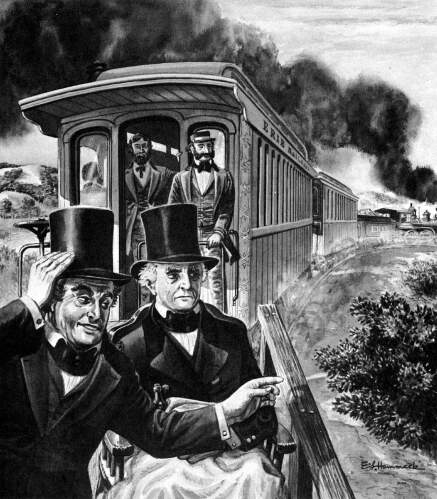

When President Fillmore, the members of his cabinet, and other

distinguished guests came up from Amboy on the steamer Erie

in mid-afternoon on May 13, 1851, all the shipping

in the Harbor was dressed in bunting. Batteries at Forts Hamilton

and Diamond and on Governor's Island and Bedloe's Island boomed

forth National salutes. Cheers from fifty thousand throats and

a salute from pieces used in 1776, fired by veterans of the Revolution,

greeted the President and his suite as they disembarked at the

Battery. Nine thousand militia were on hand to escort the President

to the Irving Hotel at Broadway and Twelfth Street. Webster, who

was already showing marked indications of his approaching end,

went to the Astor House, where he always stopped. An elaborate

dinner was the event of the evening.

According to

the program, the boat carrying the guests was to leave for Piermont

at 6 A.M. on Wednesday, May 14, 1851. There was a pouring

rain that morning, but, despite the unearthly hour and the rain,

the streets were packed with people to cheer the departing guests.

A blundering porter was slow with Webster's baggage, and the boat

did not get away until 6:10. According to

the program, the boat carrying the guests was to leave for Piermont

at 6 A.M. on Wednesday, May 14, 1851. There was a pouring

rain that morning, but, despite the unearthly hour and the rain,

the streets were packed with people to cheer the departing guests.

A blundering porter was slow with Webster's baggage, and the boat

did not get away until 6:10.

The famous Dodsworth's Band, which had been engaged to accompany

the party to Dunkirk, rendered an elaborate program on the way

up the river. Another very important member of the party was George

Downing, the most famous caterer of his day, who had with him

a picked corps of waiters, whose duty it was to see that no one

lacked refreshment, liquid or solid.

On arriving at Piermont, at 7:45 A.M., the party was received

with the ringing of bells, the booming of cannon, and the cheers

of a multitude. The two trains which were to carry the invited

guests were decorated with bunting, and there were flags and banners

everywhere.

At eight o'clock the first through train that ever carried

passengers from the ocean to the Lakes pulled out of Piermont,

and was followed seven minutes later by the second section. President

Fillmore was on the first section, and Webster was on the second,

seated in a comfortable rocker on a flat car, for the rain had

ceased and he wanted to enjoy the scenery to the utmost.

The only man on either train who was not happy was Gad Lyman,

the engineer of the first section. Gad had not got many miles

out of Piermont before his engine, a Rogers, No. 100, manifested

unmistakable symptoms of "laying down." Under any conditions,

this would have been mortifying, but the peculiar circumstances

in this case made the conduct of No. 100 doubly humiliating.

In those days there was a fierce rivalry between the different

makers of locomotives, and engineers were not infrequently zealous

partisans of the various manufacturers. Some months previous Gad

had been given a new Swinburne engine, No. 71, just out of the

shop.

Being partial to Rogers machines, Gad could do nothing with

the new Swinburne. On the strength of his reports the 71 was condemned

as worthless, and Gad was given the new Rogers, with which he

declared he could pull the Hudson River up by the roots if he

wanted to.

Josh Martin, another engineer, was a warm personal friend of

Swinburne, the maker of the 71. Josh asked for the 71 after it

had been condemned, and after much solicitation was given profane

permission to take the old thing and go to blazes with it.

On this memorable day, after Gad's vaunted No. 100 had laid

down on a little hill, a messenger was sent to a siding near by

for a plebeian gravel-train engine to help him into Port Jervis,

where he arrived an hour late and inexpressibly crestfallen to

find Josh Martin waiting with the 71 to take his train.

Swinburne, the locomotive-builder, who was on the train, hurried

forward and climbed on the 71. Josh slapped him on the back and

exclaimed:

"Swinburne, I am going to make you to-day or break my

neck!"

Josh didn't break his neck, but every one on board the train

was fully persuaded his own neck would be broken, for Josh covered

the thirty-four miles from Port Jervis to Narrowsburg with the

heavy train in thirty-five minutes. Such a record as that had

never been approached in the history of railroading.

Swinburne was in raptures, the officers of the road were astounded,

and some of the distinguished passengers were so nervous that

they insisted on getting off and walking. By the time they had

covered the eighty-eight miles from Port Jervis to Deposit, Josh

had made up the hour Gad had lost.

At every station along the route there were cheering crowds,

booming cannon, waving banners, and oratory. Wherever the trains

stopped long enough, some of the distinguished guests would make

brief speeches. As the observation platform, since found so convenient

in National campaigns, had not then been thought of, the orators

held forth from flat cars attached to the rear of the trains for

the purpose. One of these flat cars was also occupied by the railroad

official who had been designated to receive flags. By a singular

coincidence the ladies at every one of the more than sixty stations

between Piermont and Dunkirk had conceived the idea that it would

be as original as it was appropriate to present a flag wrought

by their own fair hands to the railroad company when the first

train passed through to Lake Erie. As it would have consumed altogether

too much time to make a stop for each of these flag presentations,

the engineer merely slowed down at three-fourths of the stations

enough to allow the flag officer to scoop up the banner in his

arms much like the hands on the old-fashioned Marsh Harvesters

gathered up armfuls of grain for binding. At the end of the journey

the Erie Railroad had a collection of flags that would have done

credit to a victorious army.

The party reached Elmira, two hundred and seventy-four miles from

New York, where the night was to be passed, at

7 P.M. As the President alighted a national salute was fired.

There was an imposing procession to escort the President to one

hotel and Webster to another; two banquets were served, with Downing,

the caterer, and his staff helping the hotel men.

All night long the streets were filled with enthusiastic crowds.

Hospitality was unbounded, and many citizens on all other occasions

staid and sober men grew hilarious as the night wore on. Elmira

has never had another such night as that which marked the opening

of the Erie from the ocean to the Lakes.

At 6.30 A.M., on Thursday, May 15, the special trains left

Elmira for Dunkirk., where they arrived at 4.30 P.M.

The scenes of the day before were repeated at every station

along the way. H. G. Brooks, an engineer, ran his locomotive out

several miles to meet the trains, which had been consolidated

for entering Dunkirk, and escorted them to the station under a

canopy made of the intertwined flags of the United States, England,

and France.

There was a procession, led by Dodsworth's Band, to the scene

of a barbecue for which the whole country had been preparing for

weeks.

There were two oxen barbecued, ten sheep, and a hundred fowls;

bread in loaves ten feet long and two feet wide, barrels of cider,

tanks of coffee, unlimited quantities of ham, corned beef, tongue

and sausage, pork and beans in vessels holding fifty gallons each,

and vast quantities of clam chowder.

President Fillmore manifested deep interest in the pork and

beans, while Webster was attracted by the clam chowder. He was

something of a specialist in making clam chowder himself, he said.

He strongly recommended the addition of a little port wine to

give the chowder the proper bouquet. After several dinners in

as many different places, accompanied by much speech-making, the

celebration was at an end.

The first trunk line, an unbroken road five hundred miles long,

from tide-water to the inland seas, was now open for traffic,

but that was about all that could be said. It began nowhere, ended

nowhere, had no connections and could have none. The track was

unballasted, and the rolling-stock was in such bad condition that

the insecurity of travel over the road was notorious. In two months

there were sixteen serious accidents on one division alone.

Part of these anomalous conditions was due to peculiar ideas of

what a railroad should be that seem strange enough now but were

not considered peculiar in those early days. The road was built

to secure for New York City the trade of the southern part of

the State. To make sure that none of this trade should go to Boston

or Philadelphia or any other places which were casting covetous

eyes in that direction, the Erie was prohibited, under penalty

of forfeiture of its charter, from making any connections with

any other road.

Even if connections had been desired, there could have been no

direct interchange of traffic, because the Erie was built on a

six-foot gauge, while all the other roads were adopting the standard

English gauge of four feet eight and one-half inches.

When the railroad had reached Middletown, the chief engineer at

that time, Major T. S. Brown, after a trip to Europe to study

the best railroad practice there, urged a change of gauge to four

feet eight and one-half inches. He said the gauge of the fifty-four

miles of track then in operation could be changed then at a cost

of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, but his recommendations

were not approved.

When the Erie was confronted, forty years later, with the alternative

of changing its gauge or going out of business, the change was

made at a cost of twenty-five million dollars.

In this connection it is interesting to note that the problem

of gauge was not finally settled by the railroads of the United

States until 1886. Between May 22 and June 2 of that year upwards

of twelve thousand miles of railroad in the South were changed

from wide to standard gauge. The Louisville and Nashville, by

using a force of 8,763 men, was able to change the gauge of 1,806

miles of main-line and sidings in a single day.

Notwithstanding the road was built to benefit New York, its

terminus was twenty-four miles away from the city, and the company

had refused an opportunity to gain an entrance over the Harlem

Railroad. It didn't take long for some shrewd Jerseymen who were

not in the Erie directorate to see that the natural terminus of

the road was at a point in Jersey City opposite New York, and

but a very little longer for them to preempt the only practicable

route by which the Erie could reach that point. This was from

Suffern through the Paramus Valley to Jersey City via Paterson.

The Paterson and Hudson Railroad, from Jersey City to Paterson,

and the Ramapo and Paterson Railroad, from Paterson to Suffern,

were duly chartered. The former was opened in 1836, the latter

in 1848. The Erie might refuse to connect with other roads. But

no legislative flat could prevent a passenger on the Erie from

leaving it for another road that stood ready to save him twenty

miles of travel and an hour and a half of time. The Erie tried

every device of discrimination in rates and increased speed of

its boats and trains, but utterly failed to convince the traveling

public that the longest way round was the shortest road home.

On February 10, 1851, the Erie capitulated on terms dictated by

the shrewd Jerseymen, taking a perpetual lease of the short cut

to the Metropolis.

This alarmed the people of Piermont, who petitioned the legislature

to come to the rescue of their town with a law compelling the

Erie to continue to run its trains to that out-of-the-way terminus.

But the legislature, like the railroad, gave up the attempt to

prescribe routes of travel by statute and left Piermont to oblivion.

An event of far greater historical importance in the same year

was the discovery that trains could be moved by telegraph. Although

seven years had elapsed since Morse had sent his first telegraph

message from Washington to Baltimore, capitalists were still scornfully

skeptical of the investment value of his wonderful invention,

and other folk were more or less incredulous of its practical

utility. Such occasional messages as were sent began with "Dear

Sir," and closed with "Yours respectfully."

No one dreamed of using the telegraph to regulate the movements

of trains. The time card was the sole reliance of railroad men

for getting over the road. The custom, still in vogue, of giving

east and northbound trains the right of way over trains of the

same class moving in the opposite direction had been established.

If an east-bound train did not reach its meeting point on time

the west-bound train, according to the rules, had to wait one

hour and then proceed under a flag until the opposing train was

met. A flagman would be sent ahead on foot. Twenty minutes later

the train would follow, moving about as fast as a man could walk.

Under this interesting arrangement, when a train which had the

right of way was several hours late, the opposing train had to

flag over the entire division at a snail's pace.

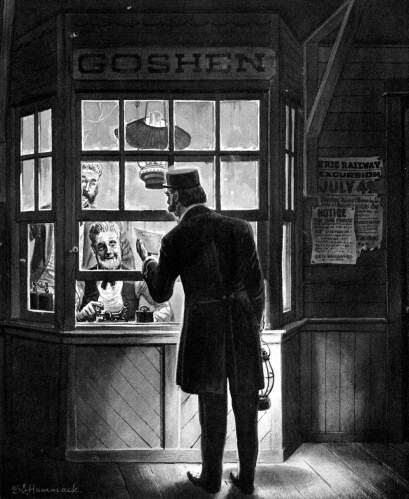

On September 22, 1851, Superintendent Charles Minot was on

Conductor Stewart's train west bound. They were to meet the east-bound

express at Turner's. As the express did not show up Minot told

the operator to ask if it had arrived at Goshen fourteen miles

west. On receiving a negative answer he wrote the first telegraphic

train order ever penned. It read as follows:

To Operator

at Goshen: To Operator

at Goshen:

Hold east-bound train till further orders.

"CHARLES MINOT, Superintendent."

Then he wrote an order which he handed to Conductor Stewart,

reading as follows:

To Conductor Stewart:

Run to Goshen regardless of opposing train.

"CHARLES MINOT, Superintendent."

When Conductor Stewart showed this order to Engineer Isaac

Lewis that worthy read it twice with rising amazement and indignation.

Then he handed it back to the conductor with lip curved with scorn.

"Do I look like a d— fool?" snorted Lewis.

I'll run this train according to time card rules, and no other

way."

Upon hearing of this Superintendent Minot used all his powers

of persuasion to induce Lewis to pull out; but the engineer refused

in most emphatic terms. He wasn't prepared to cross the Jordan

that morning, so he proposed to abide by the rules in such cases

made and provided. No other course being open Minot ordered the

obstinate engineer down and took charge of the engine himself.

Lewis took refuge in the last seat of the rear car, where he would

have some show for his life when the inevitable collision occurred,

while the superintendent ran the train to Goshen. Finding by further

use of the telegraph that the opposing train had not reached Middletown

he ran to that point by repeating his orders and kept on in the

same way until be reached Port Jervis, saving two hours' time

for the west-bound train.

The account of the superintendent's reprehensible conduct when

related by Engineer Lewis caused a great commotion among the other

engineers. In solemn conclave they agreed that they would not

run trains on any such crazy system. But Minot issued an order

that the movements of trains on the Erie Railroad would thenceforth

be controlled by telegraph, and they were.

When the Erie was at last in operation from Jersey City to Dunkirk

it had cost $43,333 a mile exclusive of equipment, or six times

the original estimate made in 1834, yet it was a railroad more

in name than in fact. Motive power and rolling stock were insufficient

and dilapidated, while the track demanded an expenditure of large

sums before traffic could be handled with profit.

But in spite of all its drawbacks this first trunk line justified

the enthusiasm of the bride which expedited its building, and

even justified the reckless language of President King, who thought

"Eventually it might earn two hundred thousand dollars a

year on freight"; for the receipts on through business in

the first six months after the line was opened to Dunkirk were

$1,755,285, and the first dividend, 4 per cent, was declared for

the last six months of 1851.

The opening of the Erie to Dunkirk and the completion of a

through route from New York by way of Albany to Buffalo a few

months later, upon the opening of the Hudson River Railroad, completely

revolutionized travel between the East and the West. People congratulated

one another on the comfort, safety, and cheapness of travel with

which, in that progressive age, the great distance between the

Mississippi and the Atlantic could be "traversed in an almost

incredibly short space of time." Before these roads were

opened for traffic the journey from St. Louis to New York was

a formidable enterprise which nothing but the most urgent necessity

could induce any one to undertake. The usual route was by steamboat

to Wheeling or Pittsburg, thence by stage through a nightmare

of rough roads, sleepless nights, stiffened limbs, and aching

heads to Baltimore or Philadelphia, thence to New York.

But the opening of the Eastern roads and of a road from Cincinnati

to Lake Erie reversed the current of travel. Instead of going

by way of Baltimore or Philadelphia to New York, nearly all the

traffic moved to Cincinnati by boat, from whence New York could

be reached by rail by way of Dunkirk or Buffalo in less than forty-eight

hours, and Washington in about fifteen hours more. This was less

time than was required to go from Cincinnati to Pittsburg by steamboat.

The routes by Wheeling and Pittsburg were practically abandoned,

while travel by the new railroads, according to the newspapers

of the day, became "almost incredibly great."

Under the circumstances, then, such superlatives as these from

the American Railroad Journal anent the formal opening

of the Erie Railroad to Dunkirk seem quite pardonable:

"The occasion was an era in the history of locomotion.

Its influence will at once be felt in every part of the United

States. The Erie Railroad is the grand artery between the Atlantic

and our inland seas. Its branches compared with other trunk lines

would be great works. . . . The New York and Erie Railroad lays

high claims to being one of the greatest achievements of human

skill and enterprise. In magnitude of undertaking and cost of

construction it far exceeds the hitherto greatest work of internal

improvement in the United States, the Erie Canal. When we consider

its length, which exceeds that of the great railway building by

the Russian Government from Moscow to St. Petersburg; when we

reflect upon the extensive tracts of country teeming with rich

products it has opened up, it is doubtful whether any similar

work exists on the earth to compare with it."

Yet Dunkirk was scarcely more satisfactory as a western terminus

than Piermont as the eastern. The struggle to create a railroad,

instead of being at an end, was only begun.

Although the first public meeting to create the sentiment which

ultimately led to the building of the Erie was held at Jamestown

in 1831, when the road was finally opened twenty years later,

that town was left thirty-four miles from the line. Being determined

to have a railroad the people of Jamestown in May, 1851, organized

the Erie and New York City Railroad to build from Salamanca, named

after the Duke of Salamanca, financial adviser to Queen Isabella,

of Spain, who was instrumental in placing a quantity of bonds

in Spain, through Jamestown to the Pennsylvania State line.

About the same time it occurred to Marvin Kent, a manufacturer

of Franklin, Ohio, that the real terminus of the Erie should be

at St. Louis through a connection with the struggling Ohio and

Mississippi, which was also of six feet gauge. Acting on this

idea he procured a charter from the Ohio legislature for the Franklin

and Warren Railroad to build from Franklin east to the Pennsylvania

State line and south to Dayton. A formidable obstacle to the execution

of this project for a through route from New York to St. Louis

and the west was the State of Pennsylvania, which interposed between

the Franklin and Warren and the Erie and New York City. There

was no railroad connection across the State of Pennsylvania between

New York and Ohio, and there was no prospect that there ever would

be any if the selfish jealousy of Erie, Pittsburg, and Philadelphia

could prevent it. These cities had resolved that all the traffic

between the East and the West through Pennsylvania should pay

tribute to them.

A combined lobby from these cities controlled the legislature

and so effectually prevented all the numerous attempts to charter

any railroad that threatened their commercial supremacy. But a

way out was found even from this hopeless situation. When it was

made an object to the Pittsburg and Erie Railroad that company

stretched its privileges to cover the construction of a "branch"

across Pennsylvania that would make a connecting link between

the New York and Ohio roads then projected. Following the devious

ways necessary to legalize its operations, and hindered by the

delays required to capitalize it, this "branch" in the

course of seven years became first the Meadville Railroad and

then the Atlantic and Great Western. The Erie made the surveys

for this connection, which would have been so helpful, and promised

to finance it; but for several years was too desperately hard

up to fulfil that promise.

Not until the assistance of James McHenry, an Irishman, who

after being brought up in America went to Liverpool and made an

immense fortune by creating the first trade in America dairy products,

had been secured were the funds to build the Atlantic and Great

Western forthcoming. McHenry's indorsement was enough to give

the road good standing with English investors. Their capital was

lavished on the project as foreign money had never before been

lavished on anything American. Agents were kept in Canada and

Ireland to recruit labor, which was sent over by the shipload

during the Civil War.

By virtue of achievements in railroad building then unparalleled

the first broad-gauge train from the East was able to enter Cleveland

November 3, 1863. On June 20, 1864, a special broad-gauge train

arrived at Dayton from New York. From Dayton connection was made

by the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton by way of Cincinnati, and

the Ohio and Mississippi with St. Louis, thus opening a broad-gauge

route from the ocean to the Mississippi. The Atlantic and Great

Western was leased by the Erie January 1, 1869, and thus became

a link in the present main line.

Before this the Erie had become great enough to rouse the cupidity

of rival manipulators, who in their struggle for possession nearly

ruined the property. High finance was then a new art and its methods

were crude.

But the Erie survived it all, and half a century after it was

ushered into Dunkirk with such elaborate ceremony it had developed

into a system of nearly two thousand five hundred miles with annual

earnings of more than forty million dollars.

ERIE Page | Stories Page

| Contents Page

|